Here is a documentary on Edward Bawden, Broadcast on Anglia TV in November 1983. It shows Bawden in his studio and house, talking of his war work and life in art and design.

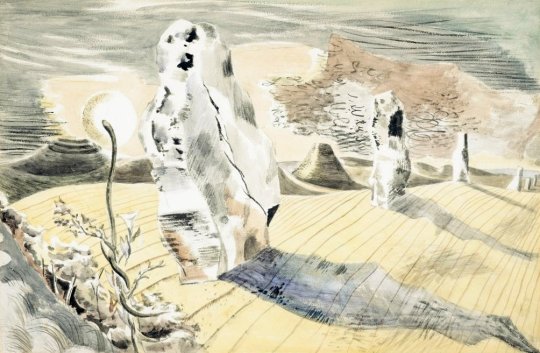

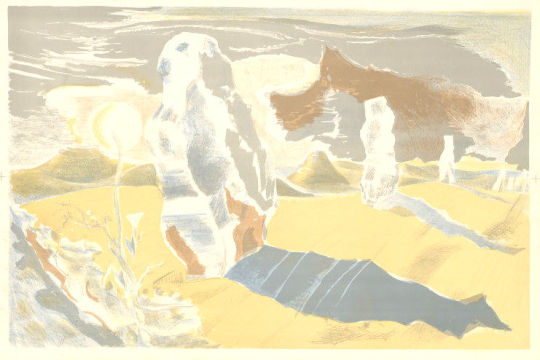

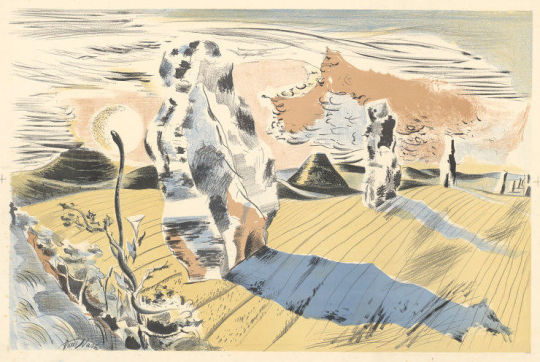

Paul Nash – Black and white negative, stone personage, Avebury, 1933

Paul Nash is one of the most distinctive and important British artists of the 20th century. He is known for his work as an official war artist during both WW1 and WW2. He also was one of the most evocative landscape painters of his generation. Nash was a pioneer of modernism in Britain, promoting the avant-garde European styles of abstraction and surrealism in the 1920s and 1930s.

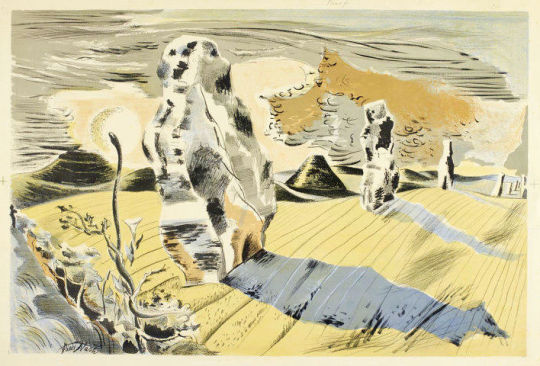

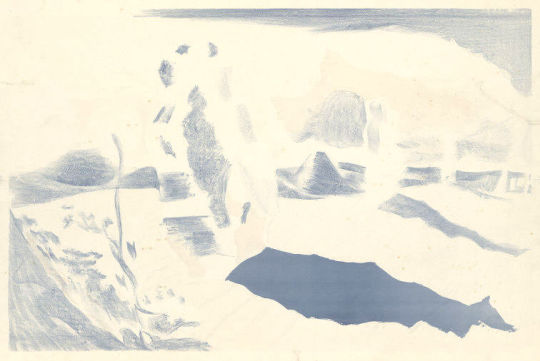

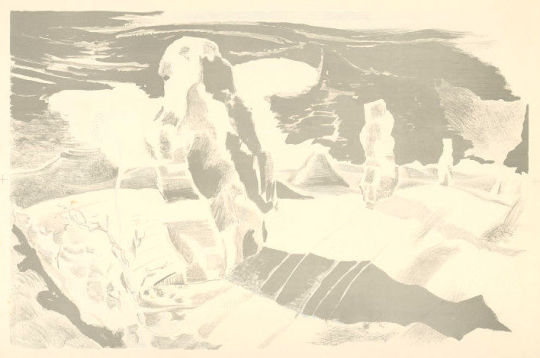

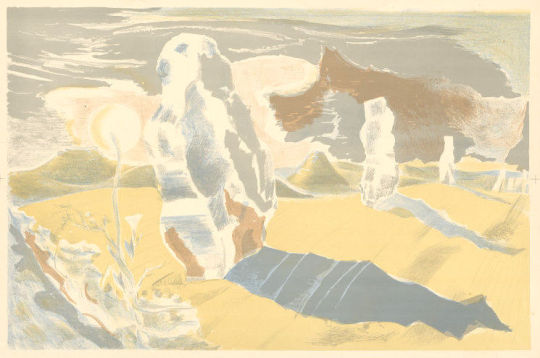

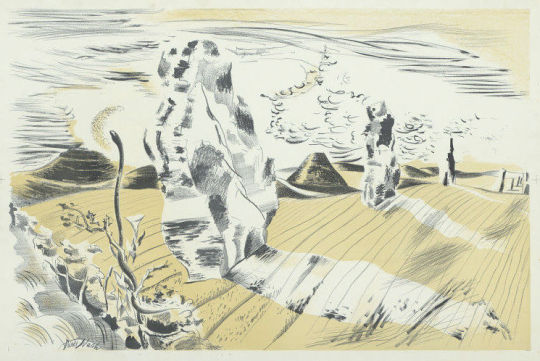

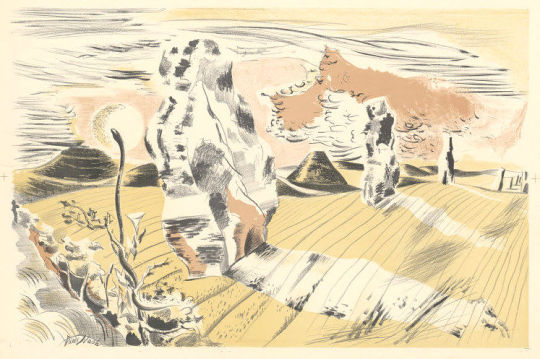

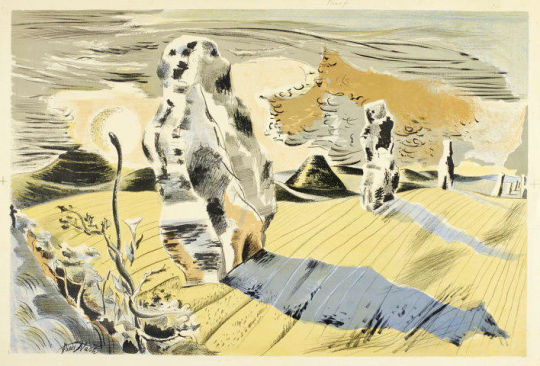

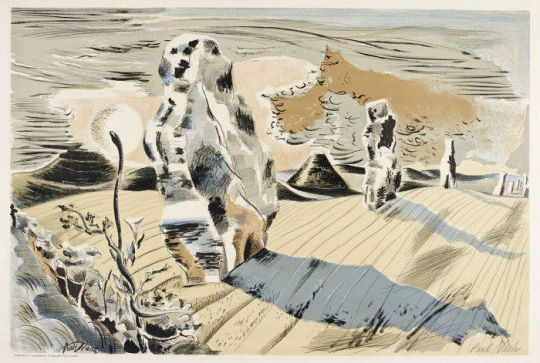

This post is about the printing process and how the Landscape of the Megaliths lithograph was made, showing each of the layers that were printed to make up the final image.

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Megaliths – Watercolour, 1937

Last summer I walked in a field near Avebury where two rough monoliths stand up, sixteen feet high, miraculously patterned with black and orange lichen, remains of an avenue of stones which led to the Great Circle. A mile away, a green pyramid casts a gigantic shadow. In the hedge, at hand, the white trumpet of a convolvulus turns from its spiral stem, following the sun. In my art I would solve such an equation. ‡

This lithograph by Nash is the bridge between romantic and surrealist art of the 1930s. Looking like a desert landscape by Dali the monoliths are both alien and familiar as Nash notes in the quote above. The convolvulus plant is a pernicious weed, I remember it covering a water-pump in the village I grew up in.

It is odd to consider that in my design I, too, have tried to restore the Avenue. The reconstruction is quite unreliable, it is wholly out of scale, the landscape is geographically and agriculturally unsound. The stones seem to be moving rather than to be deep-rooted in the earth. And yet archaeologists have confessed that the picture is a true reconstruction because in it Avebury seems to revive. ♠

Above is the original watercolour that Nash and the printers would have worked from. The colours have replaced and layered over shadow and texture. Below are many colour layers from the print showing the levels of tone and texture Nash would have used to put into the print. The main tones are printed one-by-one and then variations of tone are printed and layered, and the colours adjusted until the print is final. All the prints came from the V&A archive.

† Paul Nash by Emma Chambers, 2016

‡ The Oxford History of English Art, Volume 11 – Dennis Farr, 1979

♠ Paul Nash writing in Art and Education – March, 1939

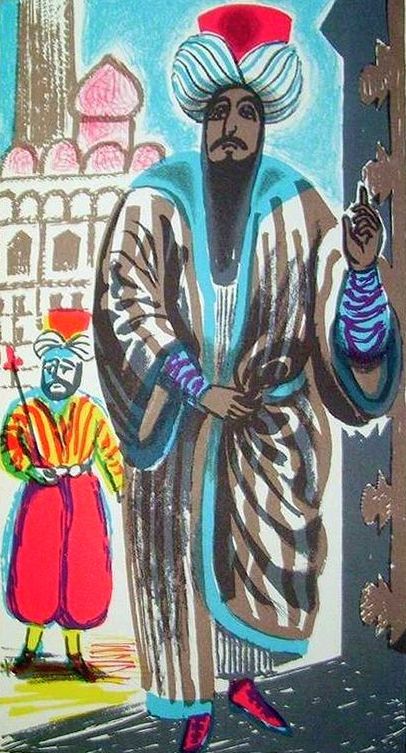

Edward Bawden – Lithograph for Travellers’ Verse, 1946.

This post is the story of Edward Bawden’s war work in the War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC) as an artist and how he used the wartime drawings and paintings in illustration work, like the The Puffin Picture Book ‘The Arabs’ but other post-war commissions.

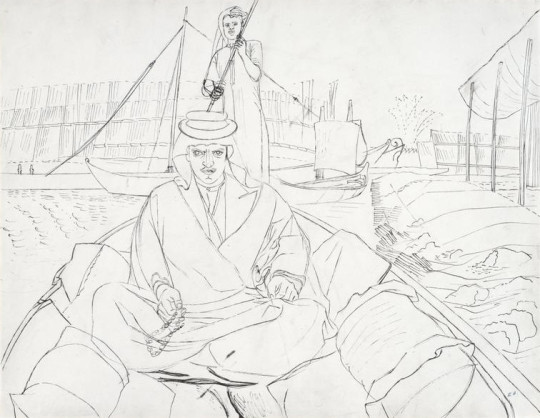

Edward Bawden – Shaikh Sharif al-Hafi, 1944.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Edward Bawden had already established a reputation as an illustrator, a comic draughtsman, a designer of typographical ornaments and patterns, a print-maker and a painter of landscapes in water-colour.

Bawden was appointed one of the first Official War Artists and was sent to join the British Army in France with Barnett Freedman and Edward Ardizzone. After being evacuated via Dunkirk, he was sent to the Middle East where he spent two years painting and drawing in Egypt, Libya, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Syria, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. During his return journey to England, his ship was torpedoed; he then spent two months in a French internment camp before being released, and arrived in England safely, only to return to the Middle East, journeying around Cairo, Baghdad, Jeddah, Teheran, Ur of the Chaldees; he was drawing all the time, finally ending his travels in Rome. †

Edward Bawden – Shaikh Raisan al-Gassid, 1944.

The WAAC recommended in December 1939 that Bawden should be appointed as an official Air Ministry artist. In May 1940, after his return from France with the withdrawal from Dunkirk. Bawden expressed his regret at having had to leave, and Dickey reported him to be “extremely anxious to be sent out again to another scene of activity”. He departed for the Middle East in July. ♦

After the war Bawden stayed in Cheltenham while repairs and work were made to his home, Brick House; It was the only building in Great Bardfield to suffer from bomb damage, but Bawden also used the opportunity to make alterations and build a studio to the back of the house. The house was used and abused by the Home Guard during the war.

John Aldridge – Builders at Work, Brick House, Great Bardfield, 1946.

Bawden’s time as a war artist had given him the advantage of travel but also an abundance of sketch books and work that were still fresh in his mind in 1945. So it was in November of that year that Noel Carrington, the head of Puffin Books at Penguin was writing to his Allen Lane, his boss about Bawden and the planned book ‘The Arabs’:

12th November 1945

I have arranged for Bawden to meet you here on Wednesday afternoon at three o’clock, so you can discuss the alternative approaches to The Arabs book with him. As an illustrator, one method will suit him as well as another. ♥

From this meeting payments were settled and Bawden took on the job of illustrating the book. The text for the book was by Robert Bertram Serjeant, Nicknamed ‘Bob’. Serjeant was a Scottish scholar, traveller, and one of the leading Arabists of his generation.

Edward Bawden – Front cover design for The Arabs, 1947.

Bawden to Carrington, 24 July 1946:

“The book is getting on slowly – I work upon the lithographs for a few hours every day, but because of the fine detail I find the work rather a strain on the eyes. In all I have finished one-fifth of the drawings but these include some of the most elaborate ones such as the two double spreads.’ ♥

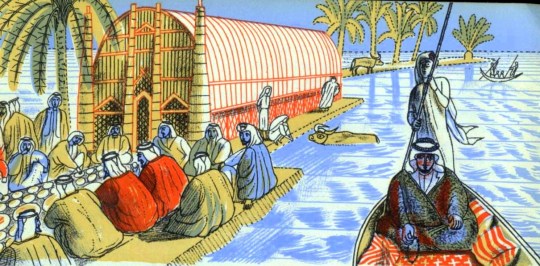

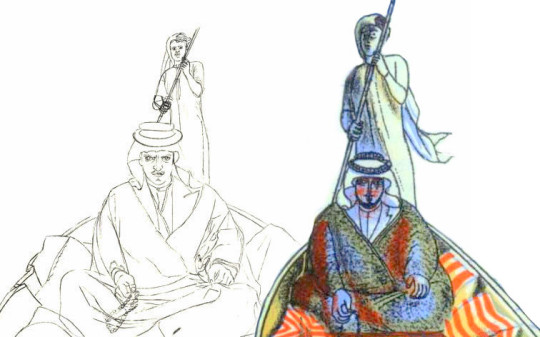

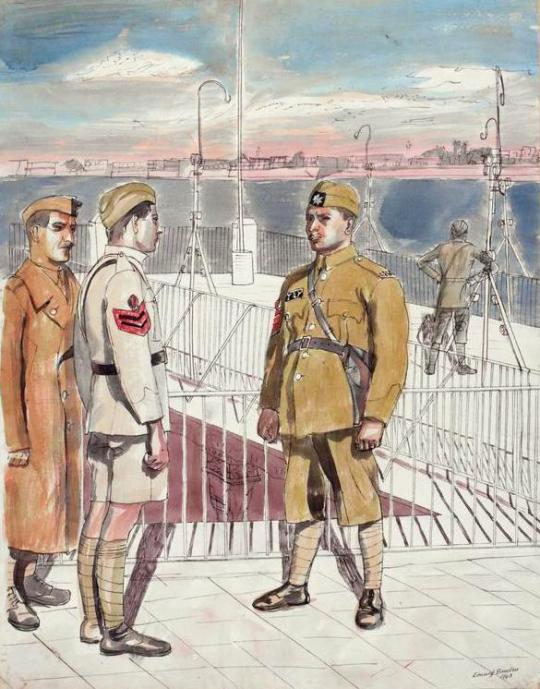

As you can see in the image below, Bawden recycled some of his paintings from the war and used them in the making of the book. The man to the right – on the boat is ‘Shaikh Sharif al-Hafi’, pictured at the top of this post.

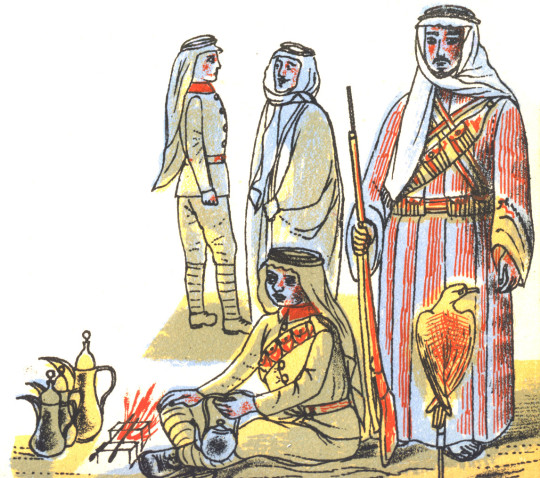

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘The Arabs’, p18, 1947.

Below I have edited both images side-by-side and you can see how the line drawing has been simplified for the lithographic process.

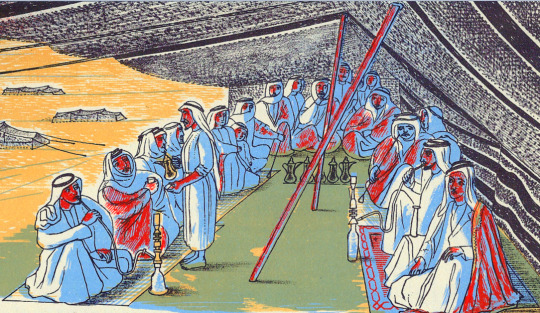

Although ‘The Arabs’ became a factual book rather than the ‘story’ title Carrington intended, it is one of the highlights of the series. Bawden’s lithographs are as good as any he completed and the two full double page spreads are superb examples of his mastery of line; Curwen made a good job of the printing. ♥

Edward Bawden – Detail from The Arabs, p30, 1947

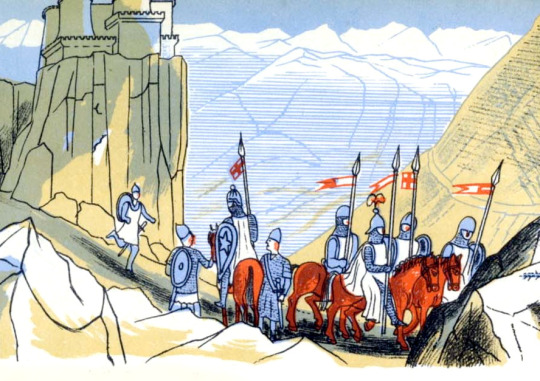

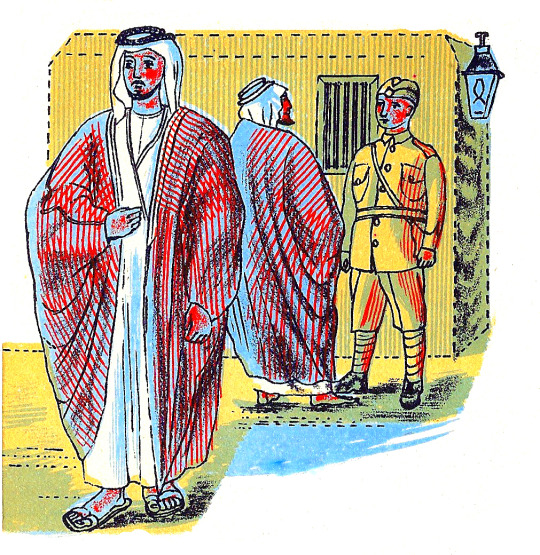

The text of ‘The Arabs’ doesn’t shy away from the Crusades and they are also illustrated as in the image above and below. The historical detail also takes in the history of the Arabic nations, how important they were during the silk road trade routes and how they declined after the European travellers sailed by boat beyond the Cape of Good Hope to China and India.

Edward Bawden – Double page spread from The Arabs, p30-31, 1947

Again, below and side by side are both the lithographed policeman from ‘The Arabs’ and the portrait Bawden painted during his war service. It really demonstrates the cheerful nature of his line drawings. It also shows how he used paintings and sketches to make the book as accurate as it could be.

Edward Bawden – Baghdad: An Illustration of Iraqi Policemen’s Uniforms, 1943

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘The Arabs’, p6, 1947

A Digital Edit of the book ‘The Arabs’ & Bawden’s War Portrait of the Policeman

The most beautiful of the two double-page illustrations is the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, 636AD, when the Rashidun Caliphate overthrew the Sasanian Empire.

Edward Bawden – Double Page Spread from ‘The Arabs’ p26-27, 1947

The Sassanid Persian army, about 60,000 strong, fell into three main categories, infantry, heavy cavalry, and the Elephant corps. The Elephant corps was also known as the Indian corps, for the elephants were trained and brought from Persian provinces in India. The Arabic side is said to have been 36,000 strong, just over half, and yet they won.

Edward Bawden – Double Page Spread from ‘The Arabs’ p27, 1947

Interestingly the book was never reprinted, and indeed could have been withdrawn and pulped! On the last pages of The Arabs, Bawden had illustrated ‘Muhammad mounted on Buraq’ ascending to the Seventh Heaven’. Obviously no one Bawden, Carrington or Lane had realised the grave offence that the depiction of the Prophet would cause.

The Cairo branch of W.H. Smith, which had ordered 5,000 copies, wrote requesting: ‘would there be any way of painting out the rider’.

Complaints flooded in and the Commonwealth Relations Office wrote to Penguin: The Puffin Picture Book No 61, entitled The Arabs, has on the last page a pictorial representation of the Prophet Mohammed and there have been in the Pakistan Press various letters protesting against this illustration.

As you no doubt know, any representation of the Prophet gives grave offence to Muslim sentiment. Although from a non-Muslim point of view such representations may appear harmless, it is none the less true that Muslim objections to representation of the Prophet in any form are based on sincere conviction.

You will, I am sure, appreciate that in inviting your attention to this matter we do not wish in any way to appear to be interfering with editorial responsibility. But we felt it right to draw your attention to the ill effects which an otherwise excellent little book may have in the Muslim world. Perhaps you would be good enough to bear this in mind should a reprint be under consideration?

One can only imagine the colour of the air when Allen Lane realised that his flagship Puffin was fatally flawed. Understandably The Arabs was never reprinted. ♥

I must add that after mentioning I was writing this post to a friend, they convinced me not to include the image of Mohammed in the blog too. If you wish to see the image you will just have to order a copy of the book to find out at your own offence.

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘The Arabs’, p15, 1947

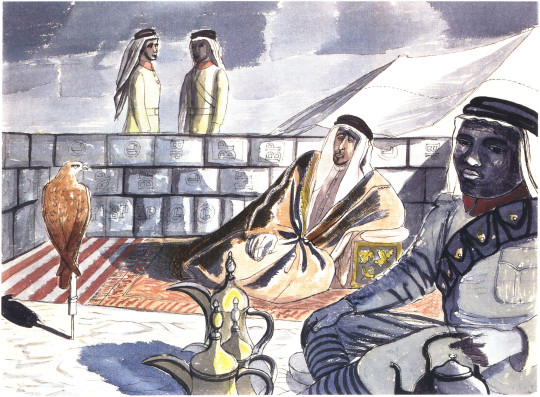

The painting below is of Mohammed Bin Abdullah El Atshan, King Ibn Saud’s representative at Rumaliya. This painting is a copy made in 1966 of a painting from 1943 made at the request of a British Petroleum executive when Bawden was painting a mural at the British Petroleum restaurant. The wall of petrol cans were given the BP logo at the executive’s suggestion.

Edward Bawden – Mohammed Bin Abdullah El Atshan, 1966

What is more curious to me about the above retrospective painting is that parts of it turn up twice in the Puffin ‘Arabs’ book. The image below in colour has the hawk, coffee pots, the boy with water-pot and two men standing behind the wall. The black and white illustration below has the drawing of the sitter.

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘The Arabs’, p7, 1947

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘The Arabs’, p25, 1947

Throughout 1946 Bawden was working on the illustrations for ‘The Arabs’ book, but it wasn’t published until 1947. Also in 1946 Bawden would illustrate a collection of poetry chosen by Mary Gwyneth Lloyd Thomas in a book called ‘Travellers’ Verse’ and he would be able to re-encounter his work of the middle east with his illustrations. These projects started to merge as parts of illustrations from his War Time Sketchbooks would end up in both.

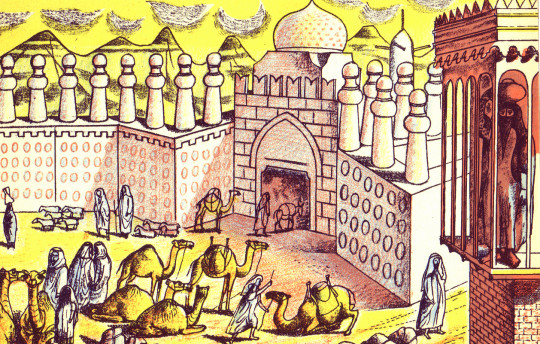

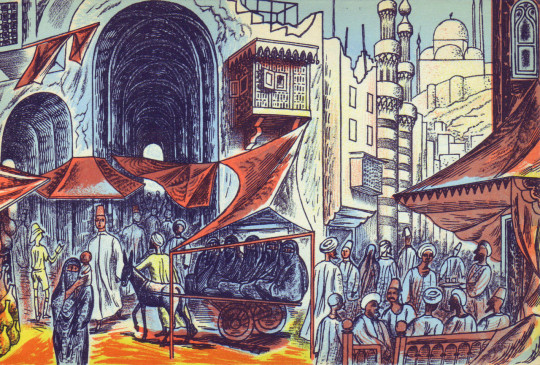

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘The Arabs’, p12-13, 1947

Above is an illustration of a Market in Cairo from ‘The Arabs’ and below is an illustration of a market from ‘Travellers’ Verse’, albeit a more fantastical version. Because ‘The Arabs’ was to be accurate the illustrations are more or less from his war paintings, but the ‘Travellers’ Verse’ book he was able to have more fun with the illustrations and be more fanciful.

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘Travellers’ Verse’, 1946

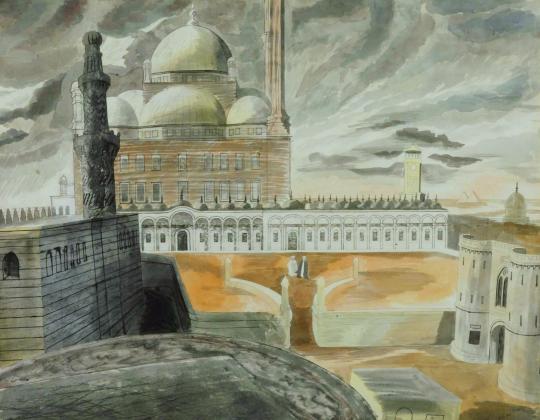

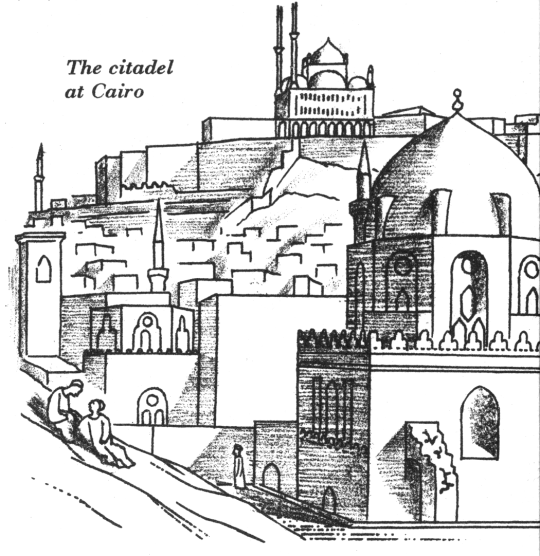

In the top right corner of the image above is the Mohammed Ali Mosque in Cairo in a simple line drawing from 1946. Below you can see it from one of Bawden’s paintings in 1941.

Edward Bawden – Cairo, the Citadel: Mohammed Ali Mosque, 1941

Bawden also illustrated the mosque, as below from the other side of the city

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘The Arabs’, p23, 1947.

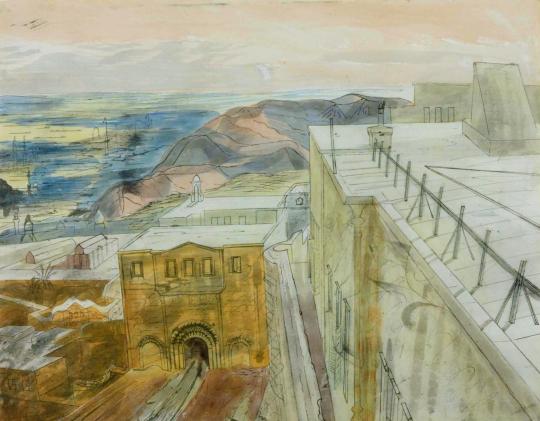

During his travels Bawden was able to stay in the centre of Cairo in the Citadel on his stay as he mentions:

Public relations could deal with journalists but they didn’t know how to deal with artists. They were puzzled and Major Asterly said ‘Why not go and stay in the citadel’, which I did and I found delightful. I made one or two drawings of the Mosque of Mohammed Ali. ♠

Edward Bawden – Cairo, the Citadel: On the Roof of the Officers’ Mess, 1941

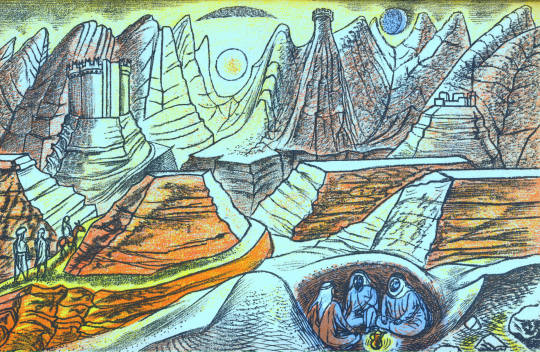

In the ‘Travellers’ Verse’ illustrations we see the city life and a fantasy of life in the countryside, with Mosque towers and street cafes to the desert landscape and camp fires.

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘Travellers’ Verse’, 1946

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘Travellers’ Verse’, 1946

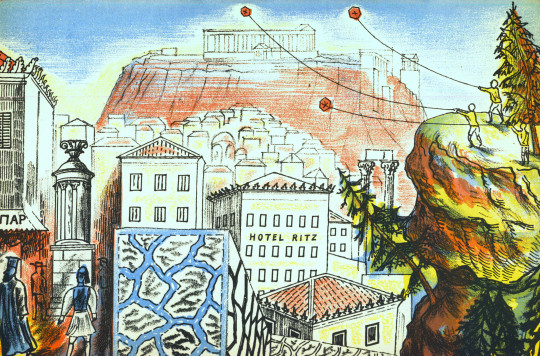

In fact Bawden would be able to use the war drawings of Greece and Rome for the other plates in the book. It seems that after Rome, Athens was a disappointment as Bawden mentions:

When I returned from Florence to Rome it was suggested that I go to Greece, so I went by air, it was the first time I had seen Greece I had been to Rome several times but I was very disappointing on the sight of Athens, it didn’t have the grandeur I was expecting. ♠

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘Travellers’ Verse’, 1946

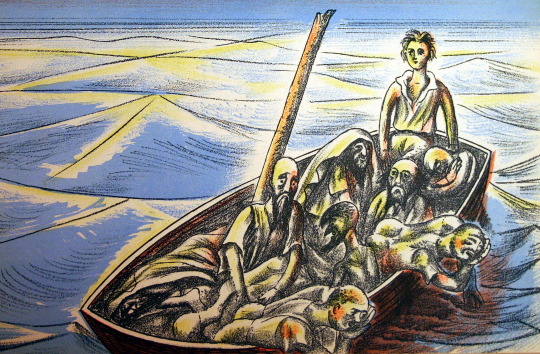

In ‘Travellers’ Verse’ the illustration of a huddled mass of bodies in a boat on a Paul Nash sea has none of the cheer the other images have. The poem being illustrated is ‘Don Juan and his tutor Pedrillo are shipwrecked.’ Bawden himself was shipwrecked during the war off the coast of West Africa on a ship from Cape Town to London. It is another translation of his wartime experiences.

Edward Bawden – Detail from ‘Travellers’ Verse’, 1946

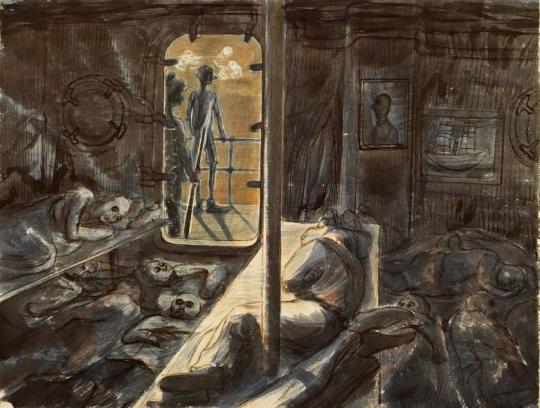

The Laconia was nearing the Equator in temperatures of 110 degrees Fahrenheit when, at 8pm on the evening of 12th September, 1942, it was hit twice below water level by torpedoes from the German U-boat U156 under the command of Werner Hartenstein.

Bawden with typical sangfroid resigned himself to death by drowning: ‘so I thought I’d wander round a bit and have a look. I went down to my cabin – I’d bought my wife a watch and thought I might as well go down with the watch as not.’ Then, ‘on returning from my cabin I saw ropes hanging down on the side where life-boats had been lowered and standing by one of these I was joined by a major. ‘After you, Sir’ I said. As he descended there was a splash. Sliding down the next ropes I found myself being gripped and guided into a boat. A few minutes later all the boats pulled away to a safe distance and there we sat waiting, still and silent and tense for the sound of the ship’s final end. ‡

Edward Bawden – Rescued at sea by the French warship Gloire, 1943.

The survivors were rescued by a French ship who were unkind to them and then taken to an internment camp in Casablanca where they stayed for two and a half months until rescued, this time by the Americans, who were kind. As a British citizen he was shipped to Norfolk, Virginia, USA before being shipped back to London.

Edward Bawden – Illustration from Vathek, 1958.

Many years after the war Bawden illustrated Beckford’s ‘Vathek, an Arabian Tale’ for the Folio Society in 1958, I find these illustrations rather weak personally, I can’t work out if he wanted to change to a looser style of lithographic illustration or if they were dashed out for the money, while technically good with colour layering, the end result in my view is poor. I rather suspect the commission came in conjunction with a larger one – ‘The Histories of Herodotus of Halicarnassus’ for the Limited Editions Club, a company like the Folio Society, but American; For them Bawden provided over 100 illustrations in a two volume book set.

He would illustrate Johnson’s ‘Rasselas’ in 1975 for the Folio Society with happier outcomes compared to ‘Vathek’, though not totally Arabian, it is a fantasy of travel.

To conclude the various Arabic styles of Bawden we should end with the giant mural for BP’s restaurant at Britannic House. The best of Bawden’s murals, using Islamic designs and architectural drawings to bold outcomes, it uses blocks of colour and pattern design much like one of his linocuts.

Edward Bawden – Fantasy on Islamic Architecture (Left Panel), 1966

Edward Bawden – Fantasy on Islamic Architecture (Right Panel), 1966

A view of the Dining Room in Britannic House.

† Ruari McLean , Edward Bawden War Artist & His Letters, 1989

‡ Malcolm Yorke – Edward Bawden and His Circle, 2015.

♠ 4622 Edward Bawden Audio Tape, IWM, 1980.

♣ R.B. Serjeant and Bawden Edward – The Arabs, 1947.

♥ Joe Pearson – Drawn Direct to the Plate, 2010

♦ Edward Bawden 1939-1944, ART/WA2/03/044/1

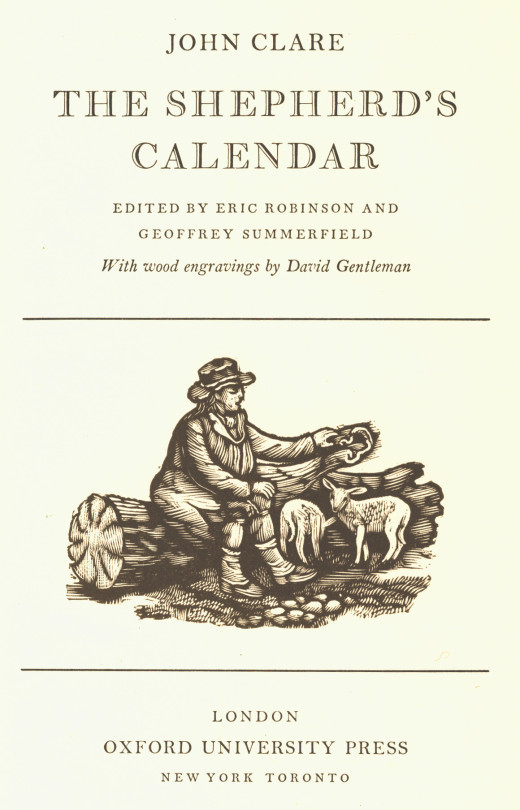

John Clare (1793 – 1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm labourer, who became known for his celebrations of the English countryside and sorrows at its disruption. His poetry underwent major re-evaluation in the late 20th century: he is now often seen as one of the major 19th-century poets.

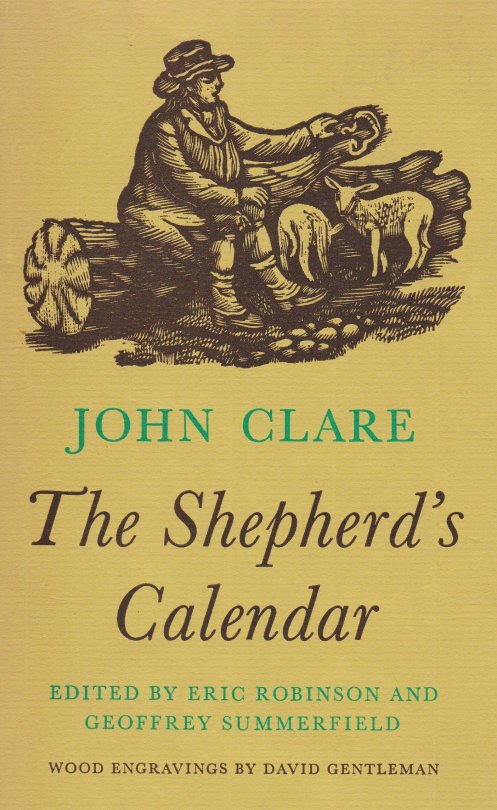

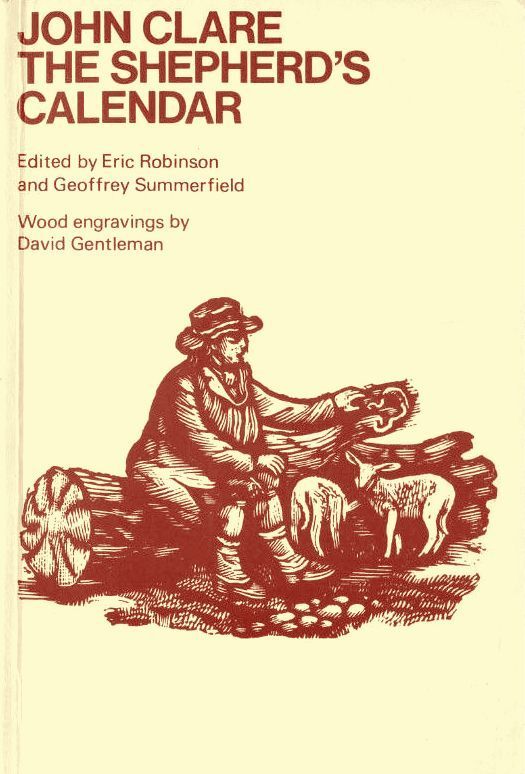

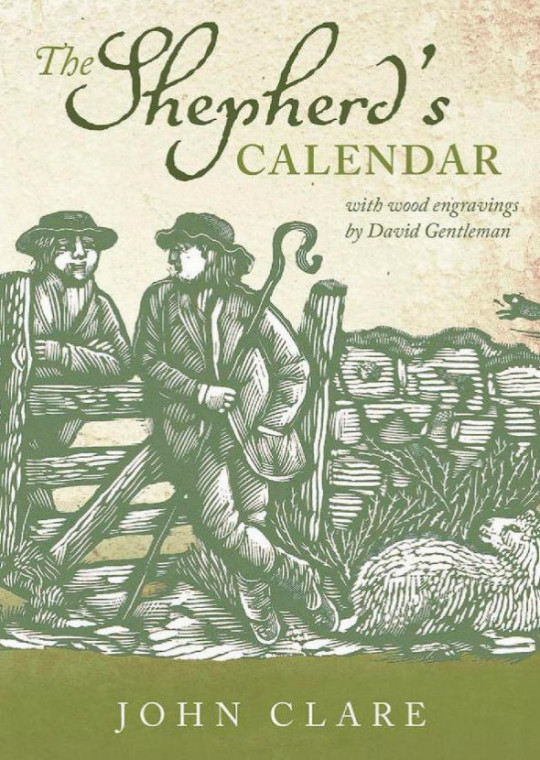

This book was published in 1964 with the monthly chapters headed by a wood-engraving by David Gentleman.

The poems of Clare have been republished many times over the years with Gentleman’s illustrations but it is interesting to look at the fashions in book-jacket design using the original illustrations.

These drawings are from the 1946 book ‘A Clowder of Cats’ an anthology of literature containing cats. The illustrations are by Edwin Smith. He was famous as a photographer and his almost annual contributions to The Saturday Book. Smith was the husband of Olive Cook, a Cedric Morris pupil and she was one of the founding members of the Fry Gallery in 1987, but together they wrote many books on cottages and stately homes.

While internationally acclaimed as a photographer, with contributions in some forty books across the world, Smith passionately wished to be recognised as an artist, and engraved, drew or painted every day, but with limited recognition during his lifetime. He was self-taught, his training being as an architect although he hardly practised before being drawn into photography.

He shared a love of the countryside, and of crafts and traditions within it, and his photography sits comfortably within the neo-romantic tradition, as was demonstrated by his inclusion in the Barbican Art Gallery exhibition on this subject in 1987 after his death in 1971. You can see more of his work here: at the Fry Gallery Page on Smith.

A short post with some of the photos I took on a trip to North Norfolk.

Here is the book ‘Home Made Wines Syrups and Cordials’ by F. W. Beech for the National Federation of Women’s Institutes. The illustrations are by Roger Nicholson. The drawings on the cover are a wonderful example of lithography on zinc. The black line drawings have a Warhol quality to them. The colours are hand drawn, each colour was painted on a different layer so when they are combined they never quite match up, I always thought it a charming effect.

The other illustrations within the book are black and white line drawings of the recipes.

In 1965, the artist and designer Roger Nicholson was working on a commemorative book to mark the 900th anniversary of Westminster Abbey. An enjoyable commission, it gave Roger a taste for designing and publishing books. So, in 1966, he produced Nicholson’s London Reference, the first of the many guidebooks that were to bear his name.

By the early 1970s, the expanding team moved to a loft-style workshop in what is now fashionable Neal’s Yard in Covent Garden. The London Street Finder was to be the most successful title.

Roger was born in Sydney, Australia, into a large family which had emigrated there at the turn of the last century. But times were hard, and in the 1930s his mother returned to England with Roger and some of his siblings and settled in Kent. After school in Rochester, he became a Medway art school student.

Then came service in the Royal Army Medical Corps in Cyprus and Egypt, after which he worked as a laboratory technician. But by 1951, an interest in interior and industrial design led him, and his brother Roger to win commissions for design work on the Festival Of Britain exhibition in Edinburgh.

The brothers’ collaboration continued in London. Their work included designing interiors, carpets and fabrics in the new Shell-Mex building in Waterloo, for the then Carlton Tower Hotel, blanket designs for the British Wool Secretariat, wallpaper designs, and newspaper textile advertisements.

Later, Roger was to become a professor in textile design at the Royal College of Art, but Roger turned to guidebooks. Yet he was no businessman, and financial and personal problems forced the sale of the company. He was retained for several years as a consultant by the new owners.

During that creative but stressful time with the guide books, Roger would take a day off a week for a country walk. He had the ability of relaxing, and making companions do likewise. He made friends easily and was very capable of striking up conversations with strangers, leaving them as if they had been long-standing friends. He was knowledgeable of plant and animal life.

After selling the guides, he explored the less-known parts of Spain, France, Greece and Turkey, where his talent for abstract landscape painting flourished. His other recreations were keeping fit, gardening and swimming.

Roger felt everyone should have equal opportunities, good value and a fair chance. When an accident put his second wife, Susi, in a coma, he would make the long journey to visit her regularly and give her the special physiotherapy himself which no medical staff could provide. Having lived in various Georgian houses in Kent, the couple moved to Brighton and then Winchelsea.

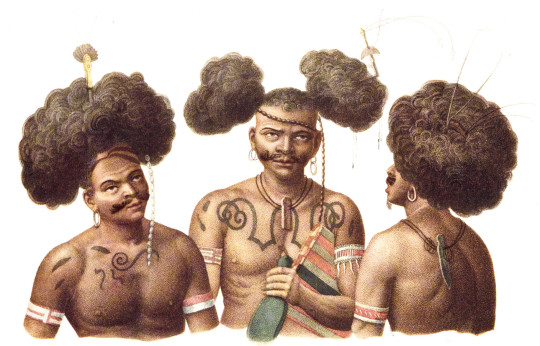

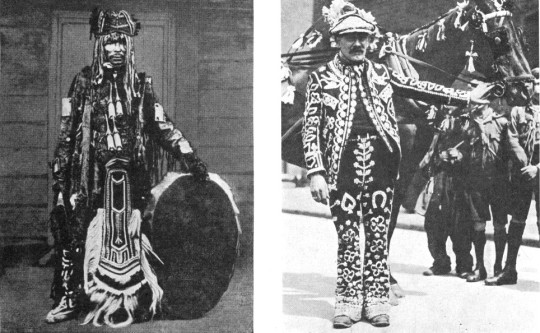

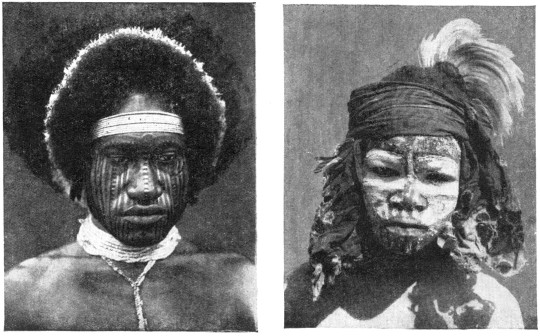

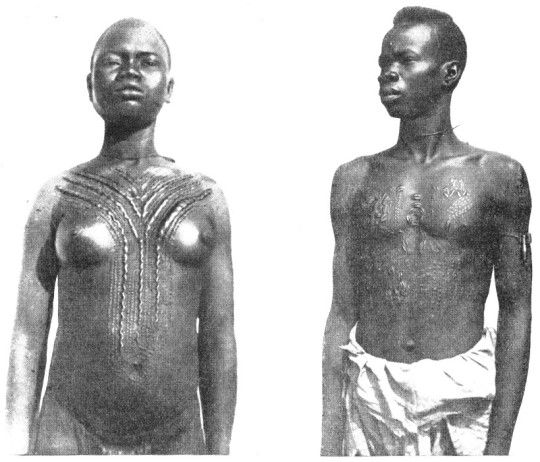

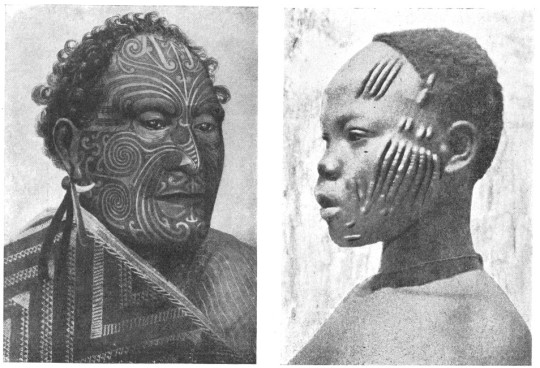

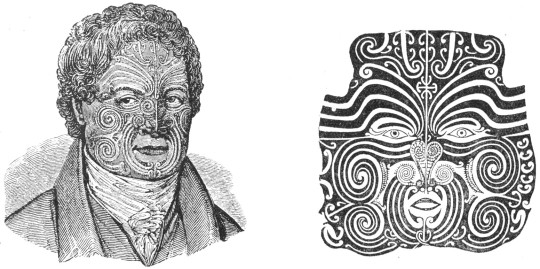

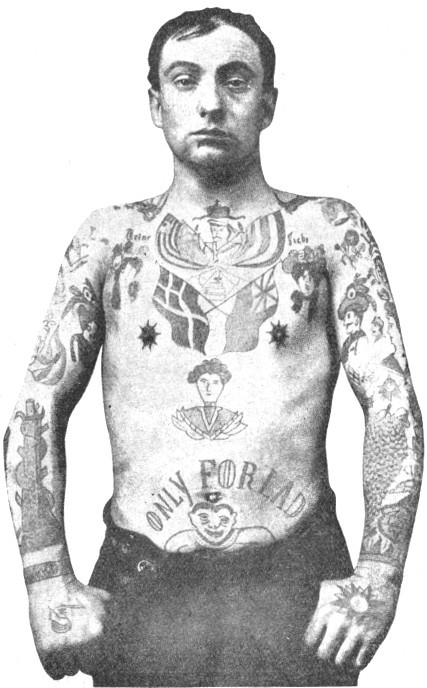

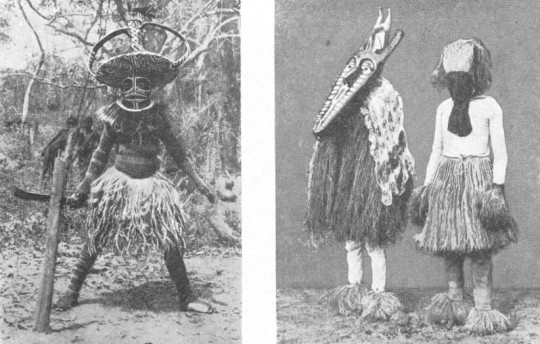

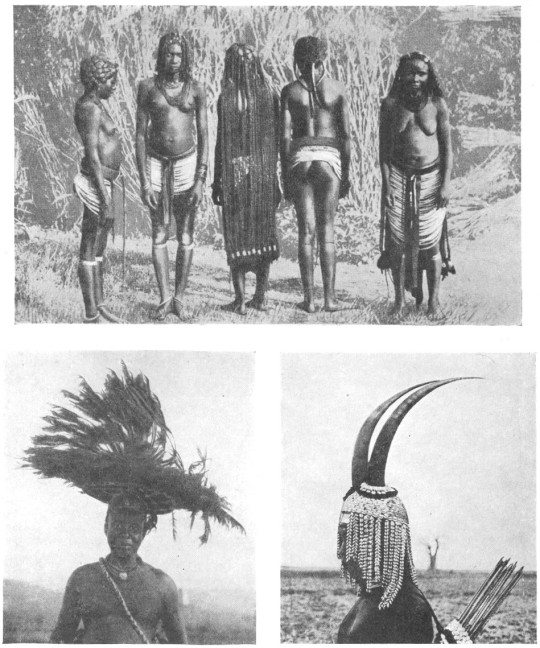

These pictures are all from a book by Hilaire Hiler ‘An Introduction To The Study Of Costume’, 1929.

The book illustrates fashion and costume through history. At just over 300 pages there are many wonderful illustrations, some of them I have pasted below.

Hilaire Harzberg Hiler was an American artist, psychologist, and color theoretician who worked in Europe and United States during the mid-20th century. At home and abroad, Hiler worked as a muralist, jazz musician, costume and set designer, teacher, and author.

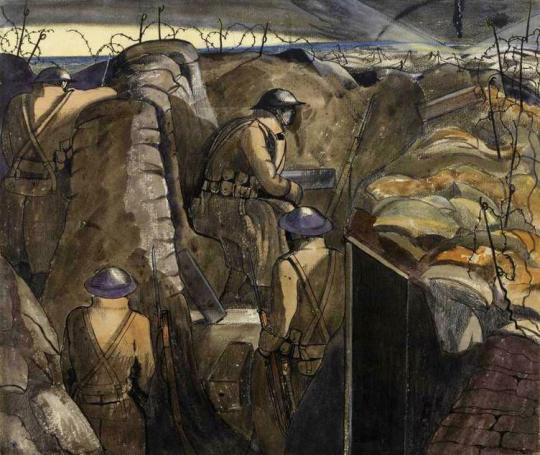

At the beginning of the Second World War Nash served in the Observer Corps, moving to the Admiralty in 1940 as an official war artist with the rank of Captain in the Royal Marines. He was promoted acting major in 1943, and relinquished his commission in November 1944.

John Nash – An Advanced Post, Night, 1918

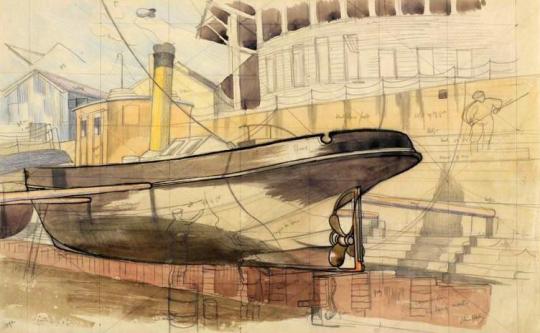

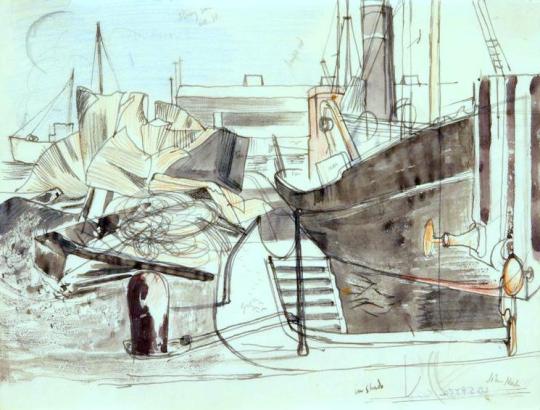

There is so much written about the paintings John Nash produced for the First World War but little on the Second. In a previous blog-post I noted that John Nash and Eric Ravilious both painted docks together in 1938 and also their letters to each other on both being invited to be war artists.

In a long interview given to the Imperial War Museum on a reel-to-reel tape machine, Nash explains this time:

The First World War paintings were the result of actual vivid experience, Second World War paintings were really more commissioned and hadn’t a very war like aspect at all.

Questioner: You were sent specifically to do a particular subject in the Second World War?

Yes I was sent to Plymouth to paint objects in the Dock Yard, and of course it’s a very beautiful dockyard and was then full of very handsome figureheads both outside in the grounds and also in some of the buildings. †

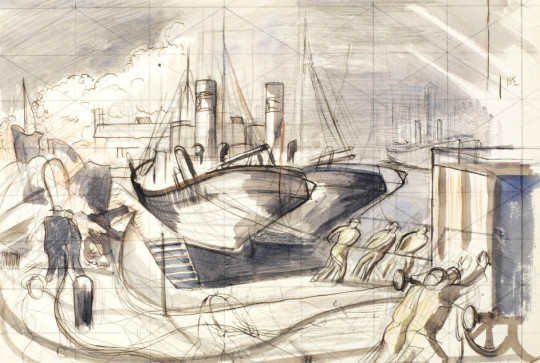

John Nash – Study of ‘Pump Room’, Plymouth Dock Yards.

But the trouble was there was a spy scare at the time, it was the period of the ‘phoney war’ and I was constantly being asked for my papers and in one case positively arrested although I was dressed up as a Royal Marine Captain, and after a time this rather got me down. In one case I actually felt afraid to do any drawing and didn’t do it when the ‘Hood’ battleship came in. I thought I must go and have a look and see if anything can be done about the ‘Hood’, I was really in a state of nerves by then that I didn’t do it – I didn’t do anything at all.

It was largely the fault of spy scares, especially amongst the dockyard ‘maties’ as they called them (men working the dockyard) who report one to the marine police on the slightest provocation. “These’s an officer there making plans” they said, I was drawing in a sketchbook you see. So at Mountbatten – the seaplane base I was arrested and marched around the camp until released by a friendly R.A.F commandant who told the officer who arrested me he got the wrong man.

But I got rather tired of this and I decided to go on elsewhere and leave Plymouth and I went to Cardiff, where they said they had nothing for me to do and from there to Swansea. I put up in a hotel in Swansea and the Staff Officer of operations there knew something of my work and knew something about me and he came out straight away to see me at the hotel and said “we don’t like you to be in this hotel (I won’t mention it) on account of security reasons, we’ll find you somewhere else to go to” and they installed me in a delightful hotel in Mumbles. But I had a very good time at Swansea because they had a awful lot to do at Swansea and were quite prepared to welcome official War Artists as a sort of additional pleasurable occupation. He kept thinking up things for me to draw and sending cars around to take you here and there, it was really very pleasant. †

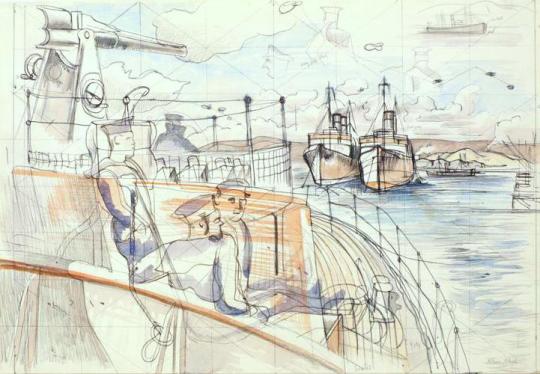

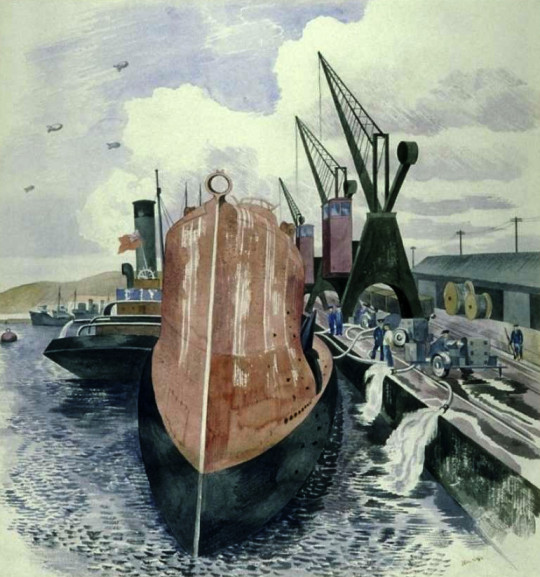

John Nash – HMS Oracle at Anchor

John Nash – Study for HMS Oracle at Anchor

I was taken up to draw a very big merchant ship which have been toed up one of the rivers there and split in half by a bomb I think… I drew this thing high and dry on the mud and then went again with the Naval numbers to see her dragged off the mud by seven tugs and then went in a car with them and drew her as she was being toed Triumphantly down the river by one tug by then. †

John Nash – Bristol Channel, with Tug Boat in the distance.

When we came back from this trip up and down the Bristol Channel we tied up in the dockyard and everybody got ready to have a (party) changed their clothes and the port was bought out and having a nice sort of evening when there was a ‘Purple Air Alarm’ and we went out on deck to see what was happening and there was a terrific explosion and everybody fell flat on the deck and the bomb landed at the end of the dock.

After that the number one officer said “I must go out and see what the Captain is doing, I think he’s gone out firefighting” ‘cause fires had started in the dock and I said “well I’ll come too.” And we spent the whole night- up to three o’clock in the morning – firefighting, dragging hoses about and what is really illustrated in that painting there. †

John Nash – Study for A Dockyard Fire

John Nash – A Dockyard Fire.

(I was) drawing in a detached way, but didn’t seem much to be like war, not that I am a fire-eater in any way. It seemed to be rather (like a) peace time occupation in the middle of a war. †

The pictures that come from the Second World War were observational documents much in the style of the Recording Britain project. During WW1 Nash was a young man but by the time of WW2 he was in his late forties and the army were less interested in giving him an active brief and they refused him opportunities to serve with the troops overseas. It maybe that the pictures Nash did for the Second World War became detached and stylishly posed but have little might or drama to interest the museums and thus also the public too.

I gave it up. I got tired of the whole thing and gave it up. I asked the Royal Marines Office to get me a job which was not an artist’s job, and so I was sent to Rosyth. It was an absolute change of life and I didn’t do any painting, really, for four years. ‡

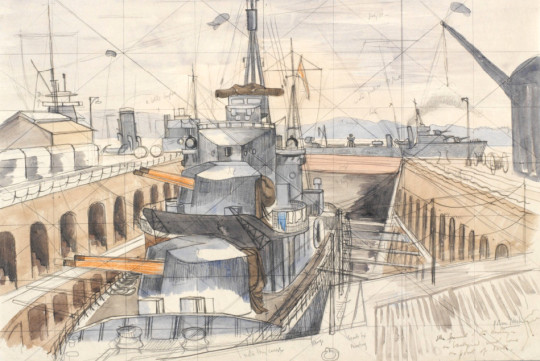

John Nash – Study for ‘Destroyer in Dry Dock’

John Nash – Destroyer in Dry Dock’

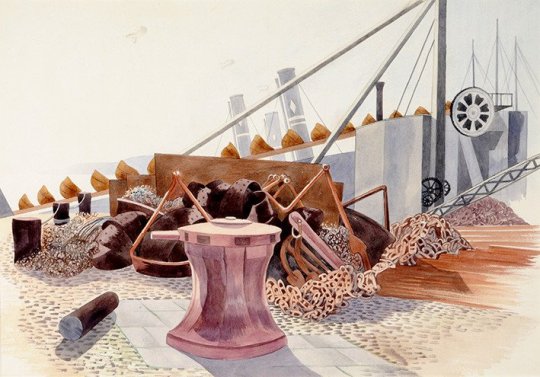

John Nash – Study for ‘Scrap’

John Nash – Scrap

John Nash – French Submarine “La Creole” in Swansea Dock, 1940

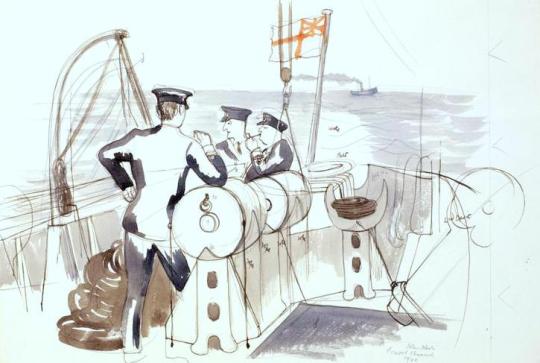

John Nash – Convoy Scene

John Nash – Study for ‘Small Vessel in Dry Dock’

John Nash – Study for ‘From the Wheelhouse’

John Nash – Study for ‘Timber’

John Nash – Study for Arming a Merchantman

John Nash would be able to return to his war work in 1947 when making an illustration for the Handbook of Printing by W S Cowell. He was illustrating The Harbours of England by John Ruskin. The figure head from the ship is clearly taken from Study of ‘Pump Room’, Plymouth Dock Yards.

† IWM – Nash, John Northcote (Oral history)

‡ Ronald Blythe – John Nash at Wormingford p12

W S Cowell – Handbook of Printing, 1947

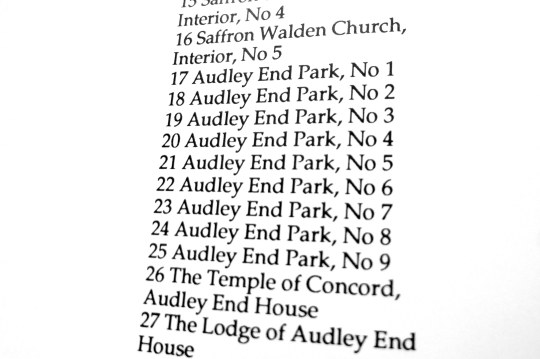

In the past two weeks I have posted about Edward Bawden and his home in the twilight of his life. This is the third and last of these posts.

The artists of Great Bardfield all reacted to their surroundings by making paintings or prints of the area that they lived, so when Edward Bawden moved to Saffron Walden in 1970, he naturally used local places in his artworks, from Bridge End Garden’s to the church.

Exhibition list from The Fine Art Society Ltd show 20/ii/1978 – 10/iii/1978.

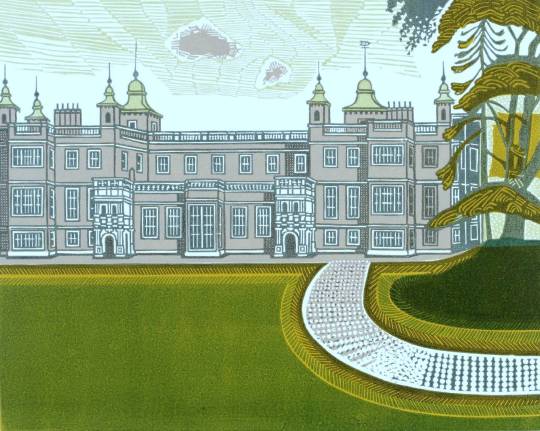

One of the biggest tourist attractions to Saffron Walden and one of the most prominent buildings in East Anglia is Audley End house and its gardens. It also was very convenient being twenty minuets walk from Bawden’s house, even for an older man.

In 1973 Bawden made a large lino cut of Audley End, a complex task to complete, with the regimented architecture of the building it is one of the more technical linocuts Bawden completed.

Edward Bawden – Audley End House, 1973

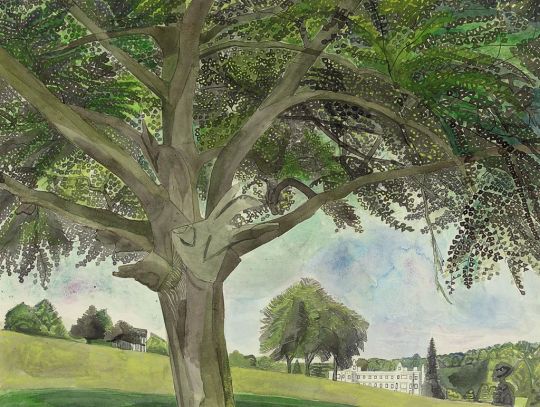

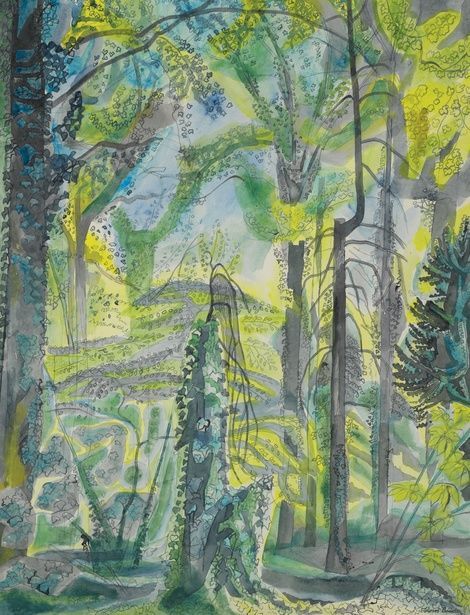

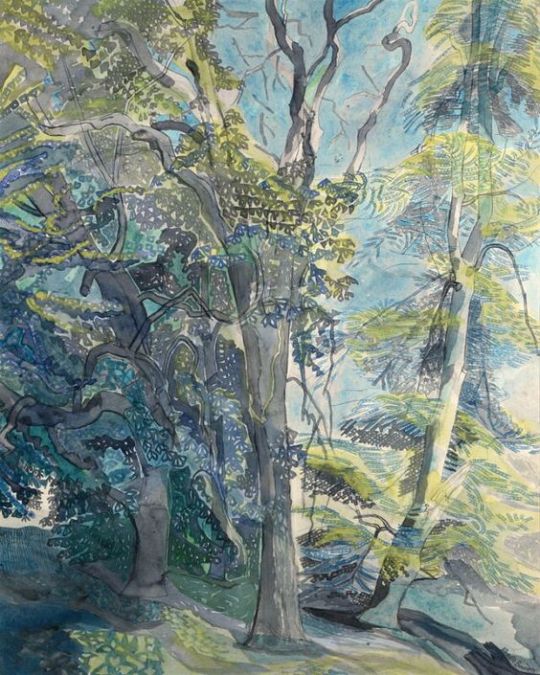

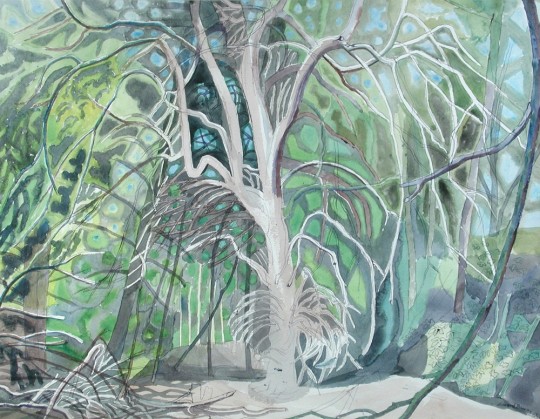

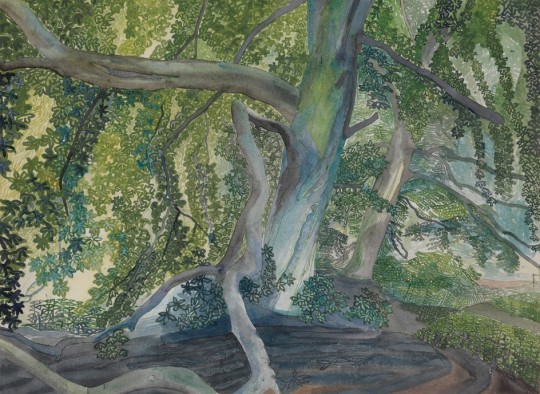

The watercolours Bawden completed where many but show off the wonderful and complex landscape of the Audley End Park, it’s follies and the trees.

Edward Bawden – The Temple of Concord, Audley End, 1975

Edward Bawden – Audley End Park III, 1975.

Edward Bawden – The Adam Temple, Audley End, 1978

Edward Bawden – Ringwood, Audley End, 1975

Edward Bawden – Ringwood, Audley End, 1975

Edward Bawden – Ringwood, Audley End, 1975

Edward Bawden – Ringwood, Audley End, 1975

Edward Bawden – In Audley End Park, 1978

Edward Bawden – Audley End, 1978

Edward Bawden – Ringwood V, Audley End, 1975