At the beginning of the Second World War Nash served in the Observer Corps, moving to the Admiralty in 1940 as an official war artist with the rank of Captain in the Royal Marines. He was promoted acting major in 1943, and relinquished his commission in November 1944.

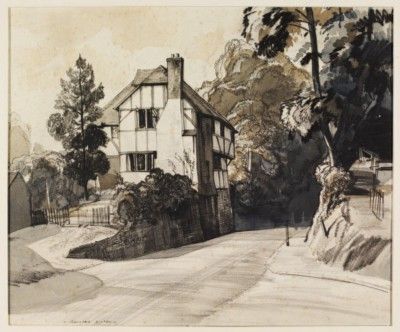

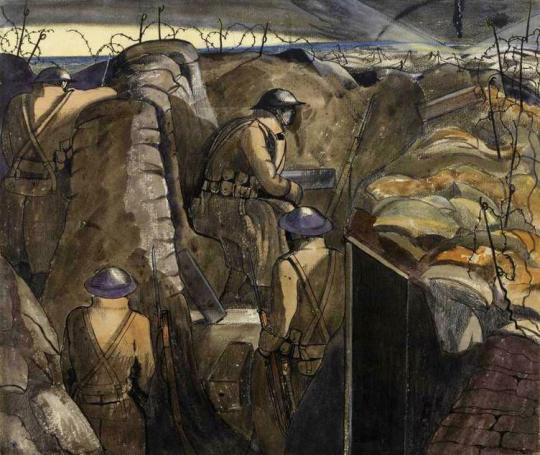

John Nash – An Advanced Post, Night, 1918

There is so much written about the paintings John Nash produced for the First World War but little on the Second. In a previous blog-post I noted that John Nash and Eric Ravilious both painted docks together in 1938 and also their letters to each other on both being invited to be war artists.

In a long interview given to the Imperial War Museum on a reel-to-reel tape machine, Nash explains this time:

The First World War paintings were the result of actual vivid experience, Second World War paintings were really more commissioned and hadn’t a very war like aspect at all.

Questioner: You were sent specifically to do a particular subject in the Second World War?

Yes I was sent to Plymouth to paint objects in the Dock Yard, and of course it’s a very beautiful dockyard and was then full of very handsome figureheads both outside in the grounds and also in some of the buildings. †

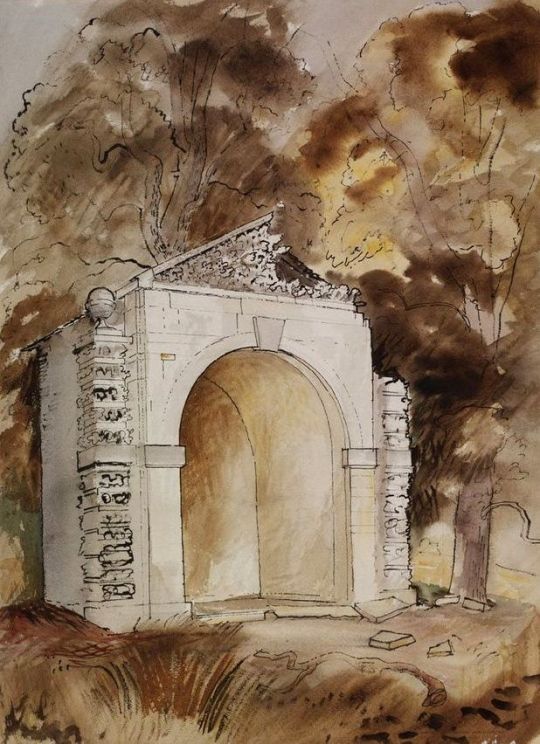

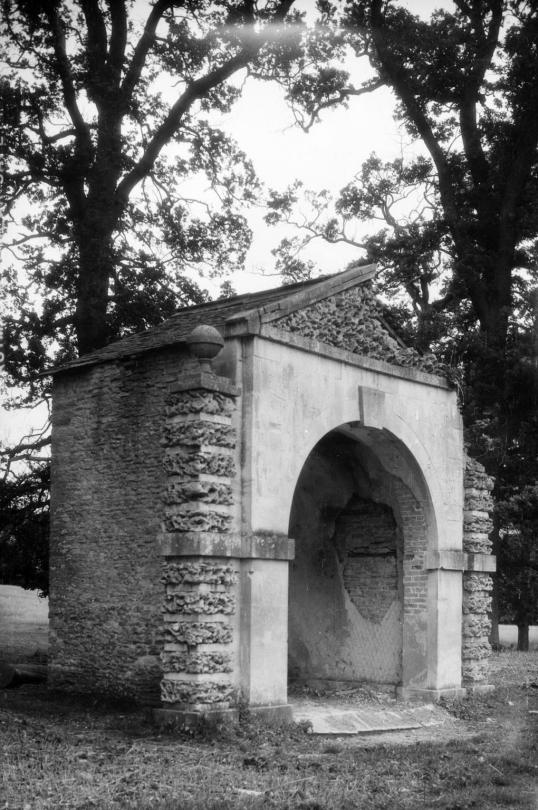

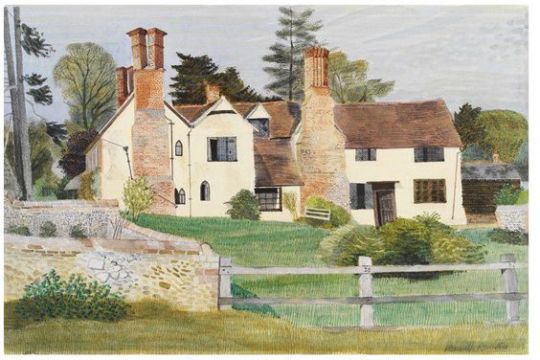

John Nash – Study of ‘Pump Room’, Plymouth Dock Yards.

But the trouble was there was a spy scare at the time, it was the period of the ‘phoney war’ and I was constantly being asked for my papers and in one case positively arrested although I was dressed up as a Royal Marine Captain, and after a time this rather got me down. In one case I actually felt afraid to do any drawing and didn’t do it when the ‘Hood’ battleship came in. I thought I must go and have a look and see if anything can be done about the ‘Hood’, I was really in a state of nerves by then that I didn’t do it – I didn’t do anything at all.

It was largely the fault of spy scares, especially amongst the dockyard ‘maties’ as they called them (men working the dockyard) who report one to the marine police on the slightest provocation. “These’s an officer there making plans” they said, I was drawing in a sketchbook you see. So at Mountbatten – the seaplane base I was arrested and marched around the camp until released by a friendly R.A.F commandant who told the officer who arrested me he got the wrong man.

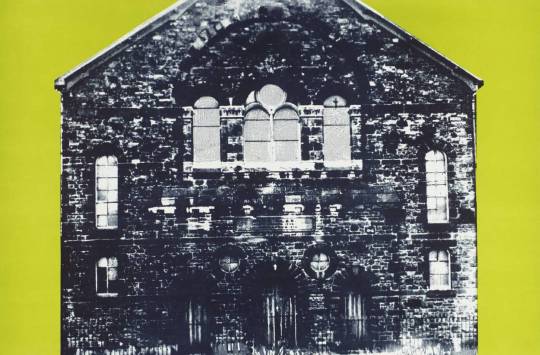

But I got rather tired of this and I decided to go on elsewhere and leave Plymouth and I went to Cardiff, where they said they had nothing for me to do and from there to Swansea. I put up in a hotel in Swansea and the Staff Officer of operations there knew something of my work and knew something about me and he came out straight away to see me at the hotel and said “we don’t like you to be in this hotel (I won’t mention it) on account of security reasons, we’ll find you somewhere else to go to” and they installed me in a delightful hotel in Mumbles. But I had a very good time at Swansea because they had a awful lot to do at Swansea and were quite prepared to welcome official War Artists as a sort of additional pleasurable occupation. He kept thinking up things for me to draw and sending cars around to take you here and there, it was really very pleasant. †

John Nash – HMS Oracle at Anchor

John Nash – Study for HMS Oracle at Anchor

I was taken up to draw a very big merchant ship which have been toed up one of the rivers there and split in half by a bomb I think… I drew this thing high and dry on the mud and then went again with the Naval numbers to see her dragged off the mud by seven tugs and then went in a car with them and drew her as she was being toed Triumphantly down the river by one tug by then. †

John Nash – Bristol Channel, with Tug Boat in the distance.

When we came back from this trip up and down the Bristol Channel we tied up in the dockyard and everybody got ready to have a (party) changed their clothes and the port was bought out and having a nice sort of evening when there was a ‘Purple Air Alarm’ and we went out on deck to see what was happening and there was a terrific explosion and everybody fell flat on the deck and the bomb landed at the end of the dock.

After that the number one officer said “I must go out and see what the Captain is doing, I think he’s gone out firefighting” ‘cause fires had started in the dock and I said “well I’ll come too.” And we spent the whole night- up to three o’clock in the morning – firefighting, dragging hoses about and what is really illustrated in that painting there. †

John Nash – Study for A Dockyard Fire

John Nash – A Dockyard Fire.

(I was) drawing in a detached way, but didn’t seem much to be like war, not that I am a fire-eater in any way. It seemed to be rather (like a) peace time occupation in the middle of a war. †

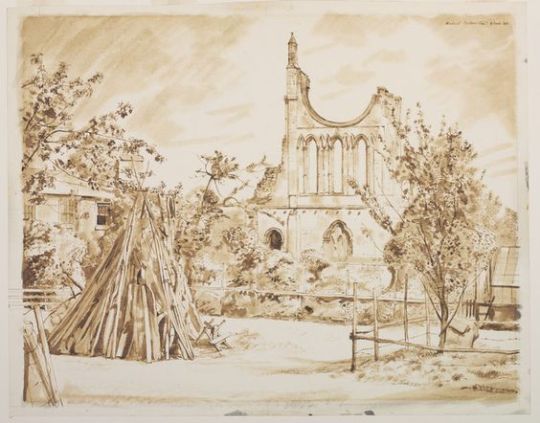

The pictures that come from the Second World War were observational documents much in the style of the Recording Britain project. During WW1 Nash was a young man but by the time of WW2 he was in his late forties and the army were less interested in giving him an active brief and they refused him opportunities to serve with the troops overseas. It maybe that the pictures Nash did for the Second World War became detached and stylishly posed but have little might or drama to interest the museums and thus also the public too.

I gave it up. I got tired of the whole thing and gave it up. I asked the Royal Marines Office to get me a job which was not an artist’s job, and so I was sent to Rosyth. It was an absolute change of life and I didn’t do any painting, really, for four years. ‡

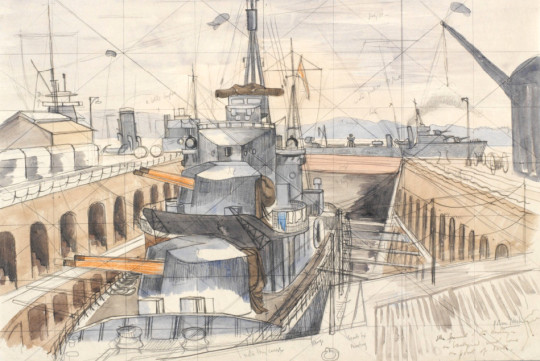

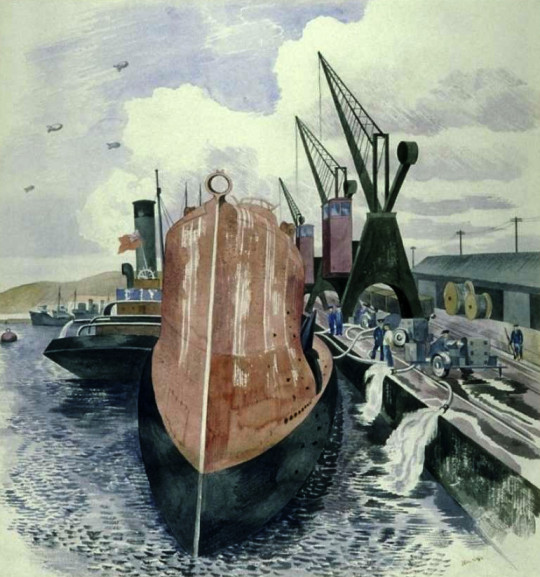

John Nash – Study for ‘Destroyer in Dry Dock’

John Nash – Destroyer in Dry Dock’

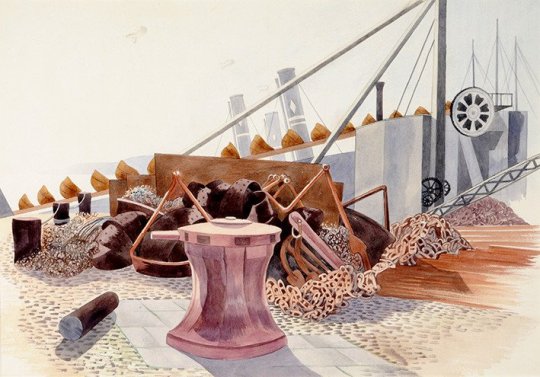

John Nash – Study for ‘Scrap’

John Nash – Scrap

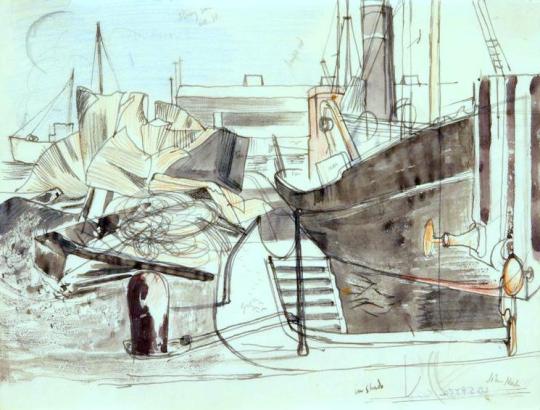

John Nash – French Submarine “La Creole” in Swansea Dock, 1940

John Nash – Convoy Scene

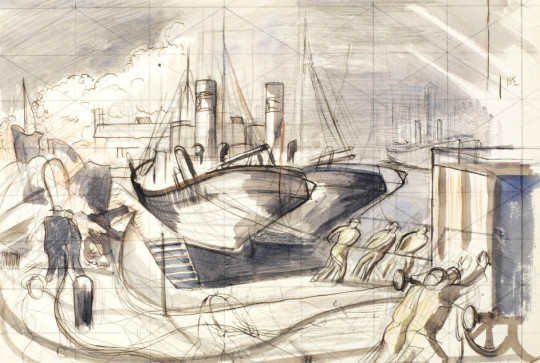

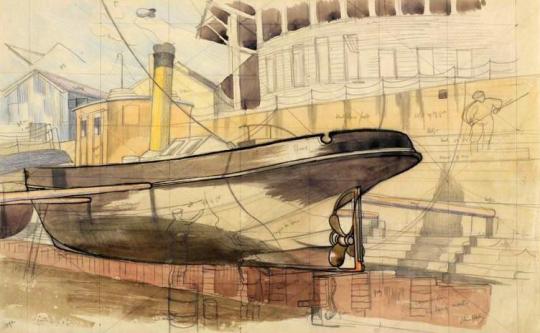

John Nash – Study for ‘Small Vessel in Dry Dock’

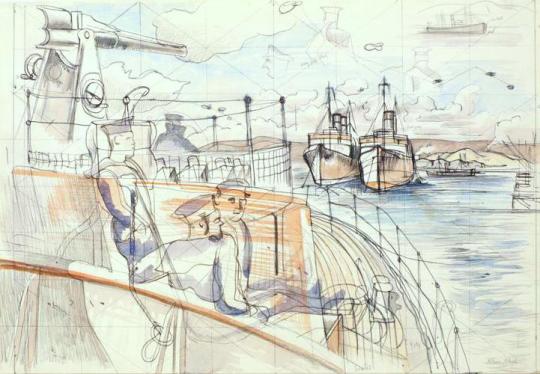

John Nash – Study for ‘From the Wheelhouse’

John Nash – Study for ‘Timber’

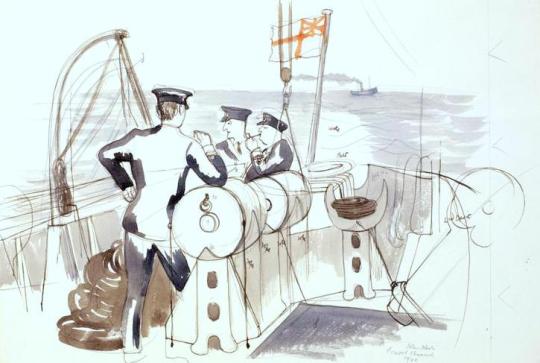

John Nash – Study for Arming a Merchantman

John Nash would be able to return to his war work in 1947 when making an illustration for the Handbook of Printing by W S Cowell. He was illustrating The Harbours of England by John Ruskin. The figure head from the ship is clearly taken from Study of ‘Pump Room’, Plymouth Dock Yards.

† IWM – Nash, John Northcote (Oral history)

‡ Ronald Blythe – John Nash at Wormingford p12

W S Cowell – Handbook of Printing, 1947