During the Great depression in America artists were employed by the state to make works for the public. It was called the Federal Art Project and from 1935 the project was mostly famous for the murals in post offices, but it also covered sculpture and graphic design work. The project is said to have made 200,000 works from 1935 to 1943.

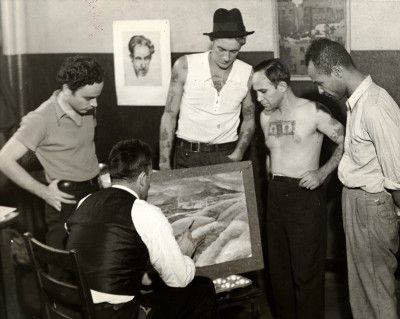

A charming picture of an Artist giving Art classes to Navy and Merchant Seamen at the Seamen’s Institute. 1935.

Vertis Hayes mural ‘Pursuit of Happiness’ painted in Harlem Hospital, NYC.

The director of the National Gallery, Sir Kenneth Clark was inspired by the Federal Art Project in the run-up to the Second World War years. In 1940 the Committee for the Employment of Artists in Wartime, part of the Ministry of Labour and National Service, launched a scheme to employ artists to record the home front in Britain, funded by a grant from the Pilgrim Trust. It ran until 1943 and some of the country’s finest watercolour painters, such as John Piper, Sir William Russell Flint, Rowland Hilder, and Barbara Jones were commissioned to make paintings and drawings of places which captured a sense of national identity.

Their subjects were typically English: market towns, villages, churches, country estates, rural landscapes; industries, rivers, monuments and ruins. Northern Ireland was not covered, only four Welsh counties were included and a separate scheme ran in Scotland.

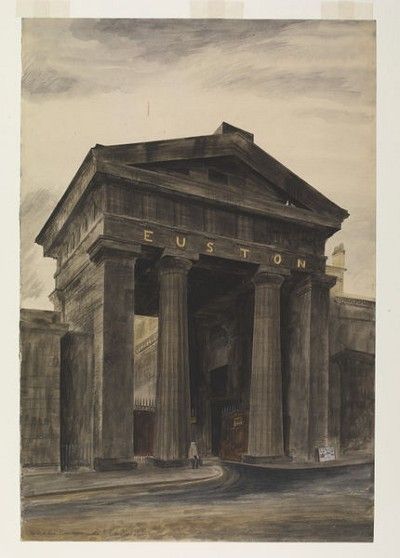

Barbara Jones: The Euston Arch for The Recording Britain project, 1943. V&A.

The premonition that Britain would be changed by WWII wasn’t the only motivation for starting the project, the ever expanding suburbs and new roads would mean that Britain was changing into a new industrial age.

The idea of a ‘vanishing Brtiain’ was also not new; in 1877 the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) was chiefly set up by William Morris and Philip Webb to conserve buildings in Britain. After the huge loss of life in the First World War, along with death duties, many family mansions where auctioned off and destroyed. (A practice that sadly went on long after the second world war.)

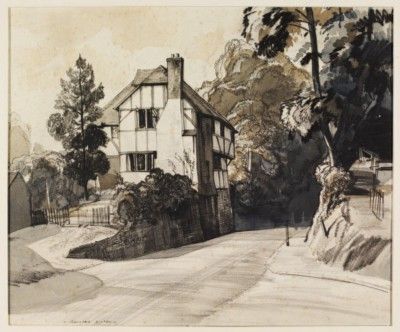

Rowland Hilder – The Old Cottage, Pulborough. 1940. V&A.

Another motivation for Clark was to help British artists during wartime and keep traditional art mediums fashionable. Many of the works were either done in watercolour or gouache.

In total over 1500 works were produced and 97 artists participated. The works were displayed three times during the war in the now, mostly empty, National Gallery and toured across Britain as a national moral boosting piece of propaganda.

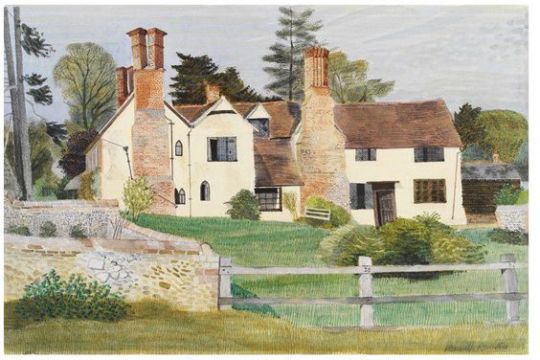

Kenneth Rowntree – Brent Hall from the South, Finchingfield. 1940. V&A.

The Pilgrim Trust donated the works to the Victoria and Albert museum, London in 1949. A four volume set of books was published and is now highly collectable. Two other books have been edited by Gill Saunders in 1990, 2011 and 2012.

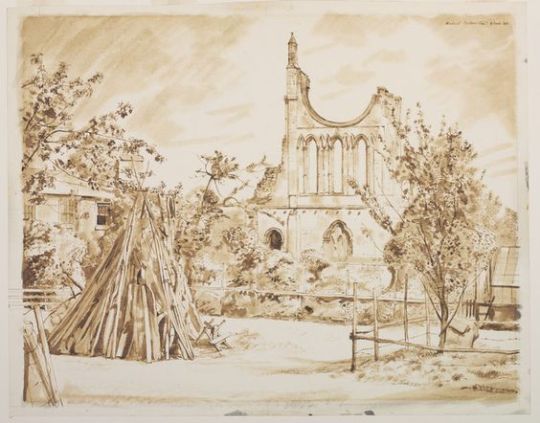

Michael Rothenstein – Byland Abbey – 4 June 1940. V&A.

These last works to Nikolaus Pevsner:

My answer to that is the War Artists’ Committee which was appointed at the beginning of the war to select artists as records of all kinds of war events. It has chosen its artists judiciously and on the whole put them into the right positions. It suggested to them subjects which were up their street anyway, and it left them an amazing amount of freedom as to how they wished to work. The result has been very good indeed. Henry Moore in the tube shelters, John Piper and Graham Sutherland amongst the bombed buildings, Stanley Spencer in machine shops, Eric Ravilious with the Fleet Air Arm, Edward Bawden in Abyssinia and so on — a record of which any country may be proud.

[And one more case-] Another group of young artists got their chance also by means of such a committee: the Recording Britain scheme of the Pi;grim Trust. Again, they were intelligently chosen to do a job of work which they liked to do: this time, the recording of anything they cared for in any county of Britain — Medieval castles, railway junctions, cottages, Victorian pubs, work in the fields, a deserted mine and iron stove and commandment boards in a church — anything. It has actually brought a few artists right into the limelight who had not before had quite such an opportunity to show what they could do: Kenneth Rowntree, for instance, and Barbara Jones. †

John Piper – Entrance Screen, Tyringham, 1940.

† From a radio broadcast ‘Art and the state’ from the show Art for Everyone. BBC Overseas Services — The Complete Broadcast Talks: Architecture and Art on Radio and Television.