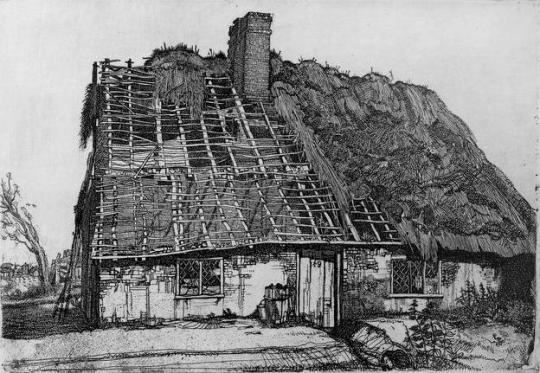

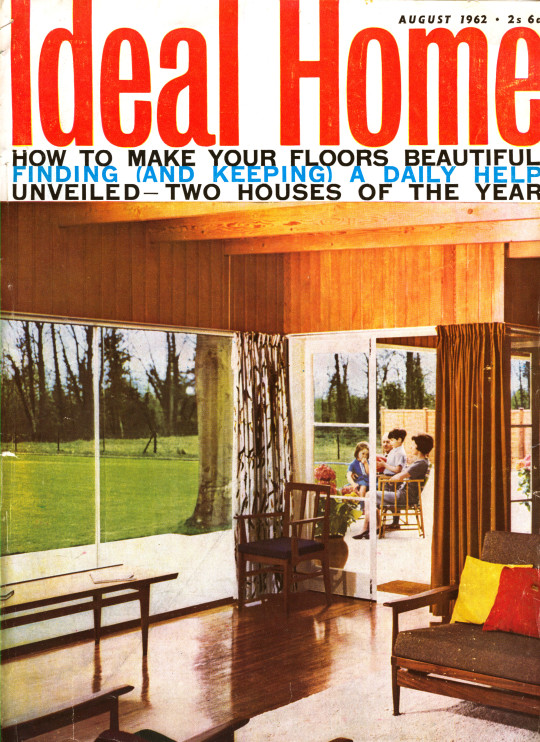

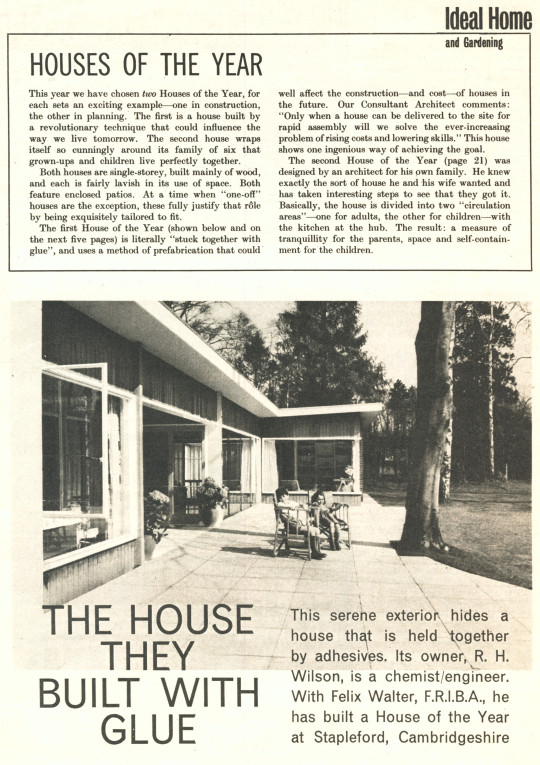

The other day I bought a vintage magazine and inside the copy were a set of photographic contact sheets for the article. The piece was on ‘The house they built with glue!’ I have copied out some of the text and posted the pictures from the magazine and the contact sheets.

The Wilson House.

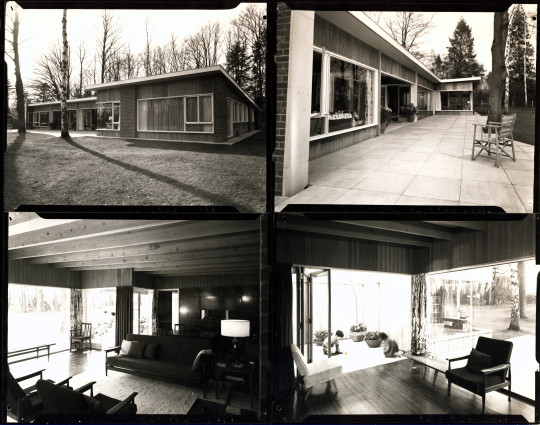

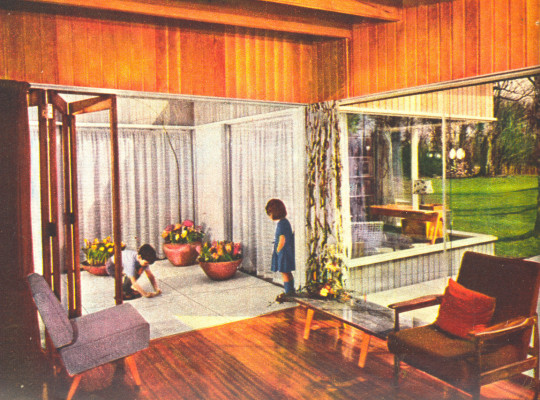

The first House of the Year is built on a delightful open site, green and peaceful, with trees screening it on two sides and a fine view to the south. Basically T-shaped, the four-bedroom house has an enclosed open-air patio in the centre to add space and light.

R.H.Wilson is a chemist/engineer who specialises in adhesives. He is sales director of CIBA (A.R.L.), the firm that developed the lightweight glued construction for Mosquitoes during the war. The adhesives used were epoxy resins, so strong that if you stick two pieces of metal together the metal will fracture before the joint breaks.

These resins are the vital components of the Wilson house. They hold the beams together. They hold the roof together. They even hold the flooring on. “The house,“ says Mr.Wilson, “would quite literally collapse and disintegrate if the adhesives failed."

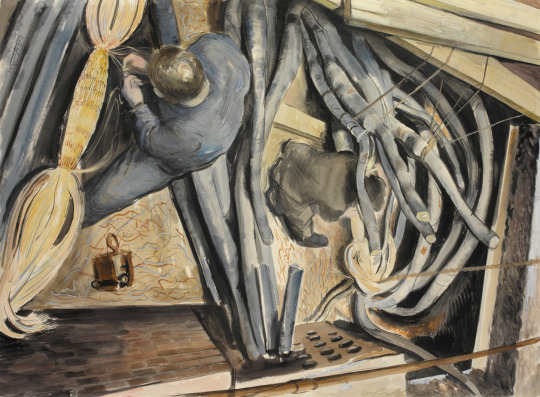

Mr. Wilson asked Felix Walter to design the house after reading Walter‘s book, Fifty Modern Bungalows. The architect chose a simple post and beam construction on a concrete slab, with walls of double glazing and cedar cladding, and brick sections for stability. The framework of the house is light and strong, based on a new type of box beam developed by the architect and W.Brown & Co. (Ipswich) Ltd. Lighter, and easier to handle than traditional solid beams, it is made from plywood, the hollow centre strengthened and stabilised with struts glued to the ply with resin. According to Mr. Wilson, “this is a staggeringly stable construction that doesn’t warp or twist like ordinary timber; it‘s economical to make and easy to erect.”

What is the significance of the techniques used in the house? Briefly, they could make future house building cheaper and faster. This is what our Consultant Architect, Eric Ambrose. has to say: “I have often stressed that the future of economic and effective house building lies in the factory-the methods used here mean that much of the house can be delivered to the site ready for rapid ‘assembly’. The lightness of the materials (the beams and the roof) means reduced cost in labour and transport. The technique makes a big advance towards the ideal of dry construction. This avoids the present necessity of having to live in wet houses holding something like sixty tons of building water that can only be dried out at comparatively high heating costs in the first year."

The shape of the outside house is beautiful, the cut of the chimney, the line of the roof beyond the garage, quite lovely.