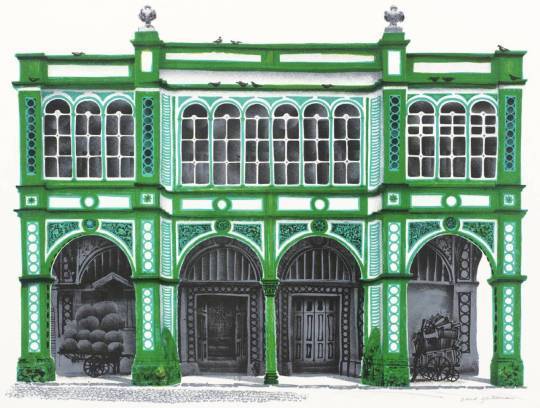

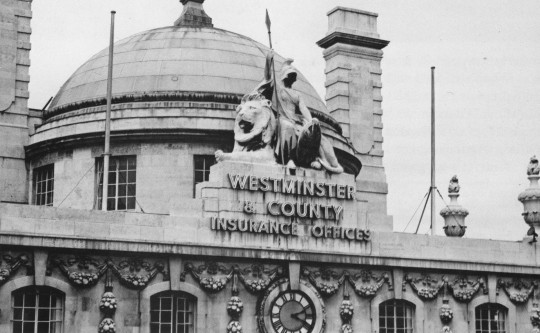

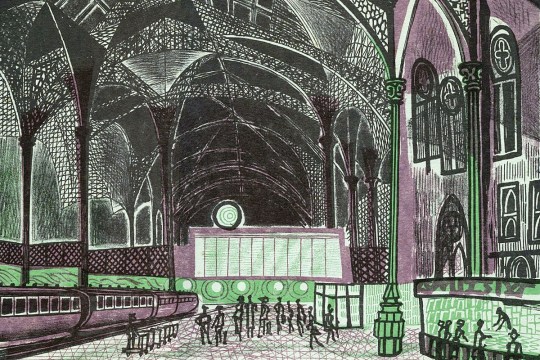

Edward Bawden – Cover illustration for The Twentieth Century, August, 1956

Edward Bawden was bought up in Braintree and after studying at the R.C.A. he moved to Great Bardfield. The nearest station was in Braintree and the terminus for the line was Liverpool Street Station, so as a student at the Royal College of Art or as a teacher there, he would have experienced the station countless times. While being interviewed for the BBC Monitor program Bawden is quoted below:

I don’t think I would have thought of Liverpool Street as a subject, as I am so familiar with it. Almost seems to me an extension of my own house. I think the ceiling is absolutely magnificent, it is one of the wonders of London. †

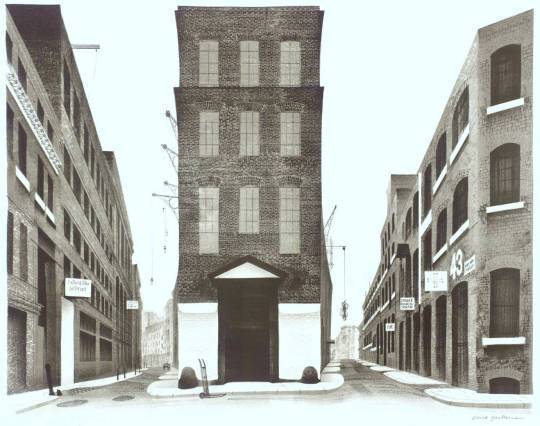

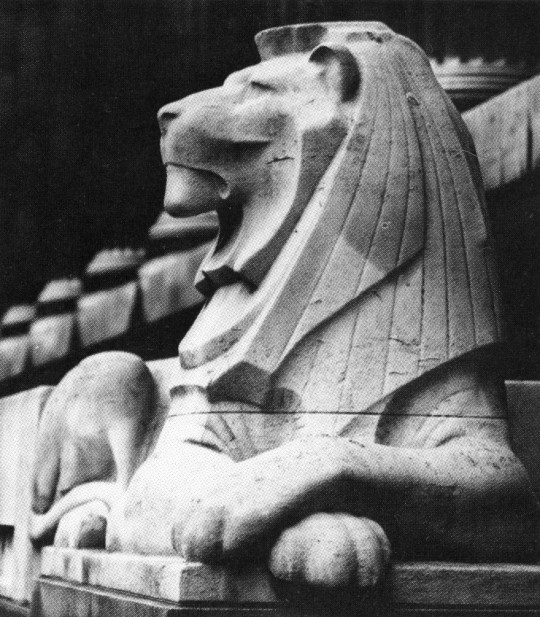

Bawden would use Liverpool Street Station in many various ways over his life, the first time is this etching done soon after he left the Royal College of Art.

Etchings for artists at this time were used like a romantic ideal of a photograph, very detailed and accurate, but edited. Few artists would use the medium like Bawden did at the time, a handful of exceptions of Christopher Nevinson and William Roberts exist. Bawden however didn’t edition many of the etchings and most of them were left to be forgotten and later reprinted in 1973. The value of Edward Bawden’s etchings is something that should be reviewed as a legacy to the medium.

Another amusing print is Mr. Edward Bawden’s engraving “Liverpool Street”, which is really humorous, not in subject, but in pattern. ‡

Edward Bawden – Liverpool Station, Etching, 1927-29

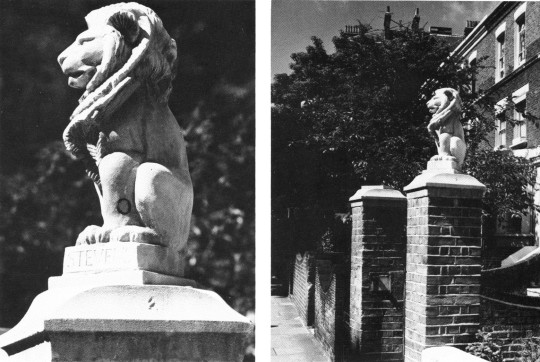

Below is a drawing used in the Sundour Diary and Notebook, a diary illustrated by Bawden in 1953 with scenes from all over Britain, a simple pen and ink drawing it captures the gothic windows and iron roof top that give the station a cathedral quality.

Edward Bawden – Liverpool Street Station, Drawing, 1953

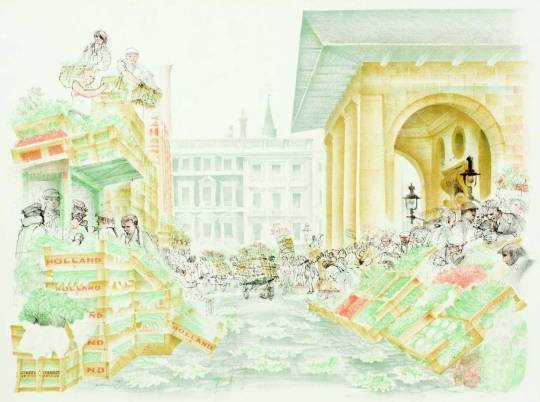

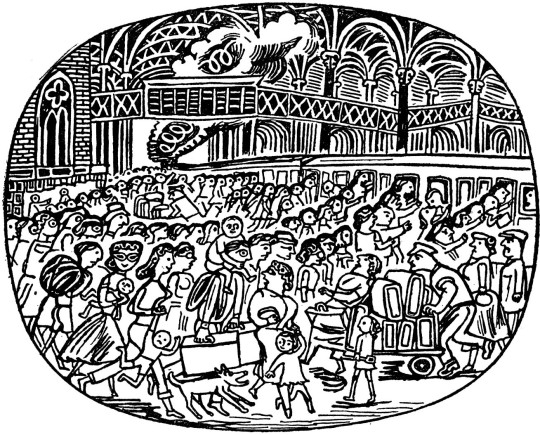

Bawden, again working in pen and ink, illustrated the cover of the Twentieth Century magazine. He would work for the magazine for three years making covers most of the months with topical themes. This illustration looks like the rush on trains to start the holidays, at the front a father with a child on his shoulders, while carrying two suitcases and followed by a dog. In front of him a luggage trolley collides with a lady.

Edward Bawden – Cover illustration for The Twentieth Century, August, 1956

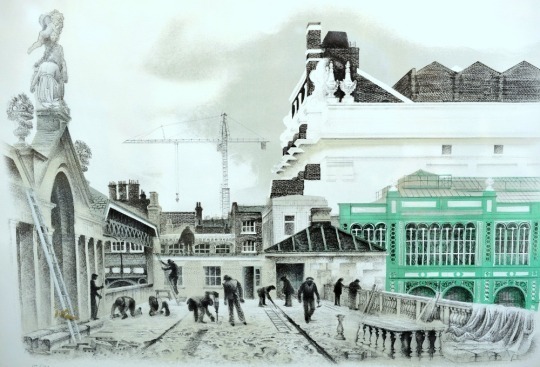

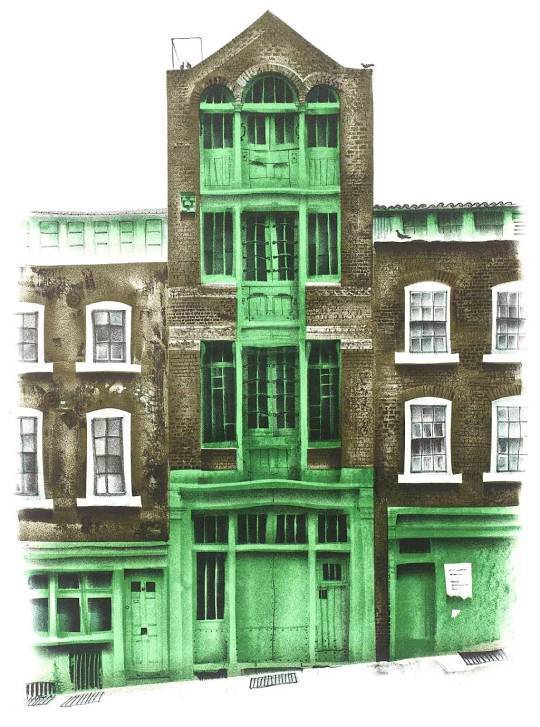

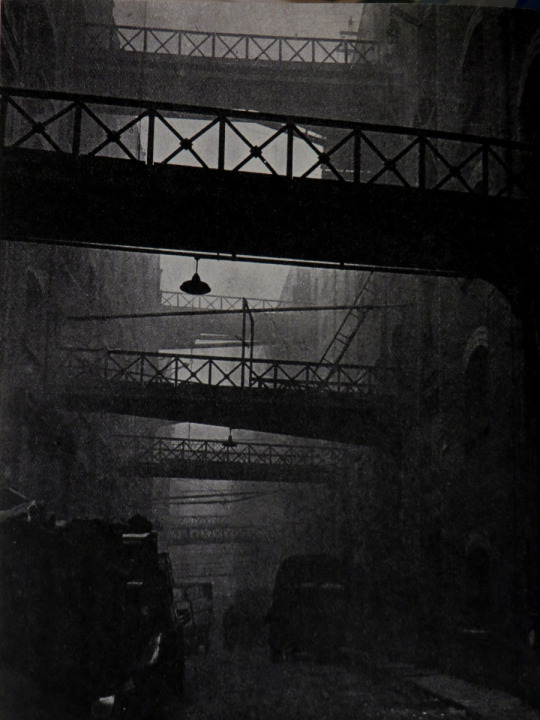

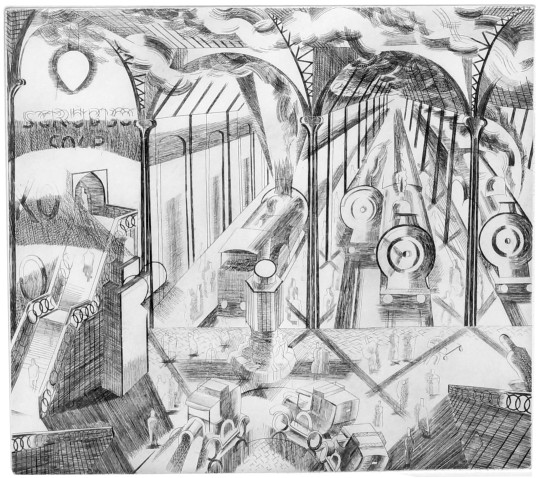

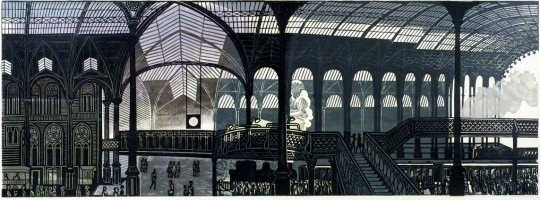

Bawden was commissioned to make two limited edition prints, one of Liverpool Street Station and one of Kings College, Cambridge, but nothing would come of that. It looks like Bawden trialled making the print in various ways, a lithograph and a linocut. The lithograph below looks almost like a pen doodle with the rooftop being a cobweb and the structure being lost in the detail. The figures on the the picture look like humans made of wire, it’s all very abstract for Bawden.

Edward Bawden – Liverpool Street Station, Artist’s Proof Lithograph, 1960

Edward Bawden – Liverpool Street Station, Linocut, 1960

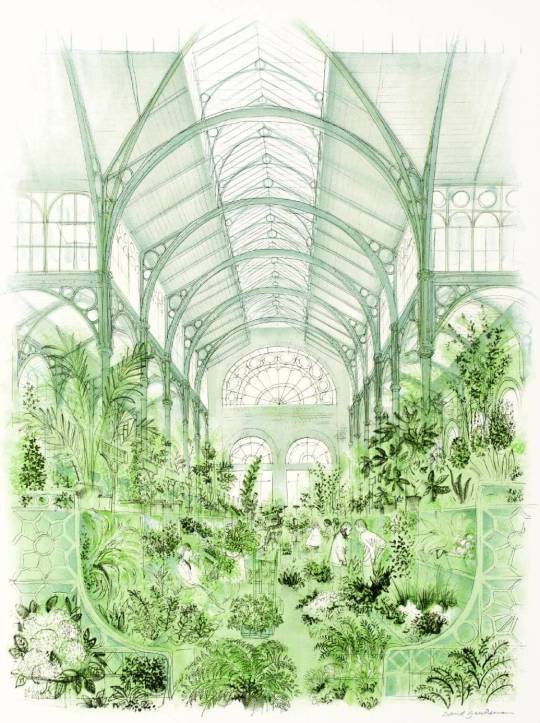

Above is the final print by Bawden after he settled on a linocut. Below is a study for the linocut as a drawing and with the perspectives bending away to the left. The main structure to the right looking like the final work. The final linocut being flatter and showing off the gothic windows.

Edward Bawden – Liverpool Street Station, Drawing, 1960

Below is a detail from the final print and a look at the repetitive detail and skill in the ironwork, rooftop and train carriages. It also shows off the over-printed steam to the right and the cut out steam to the left. And below that is another detail from the print showing the centre of the print having colour and light.

Edward Bawden – Liverpool Street Station, Linocut (Detail), 1960

Edward Bawden – Liverpool Street Station, Linocut (Detail), 1960

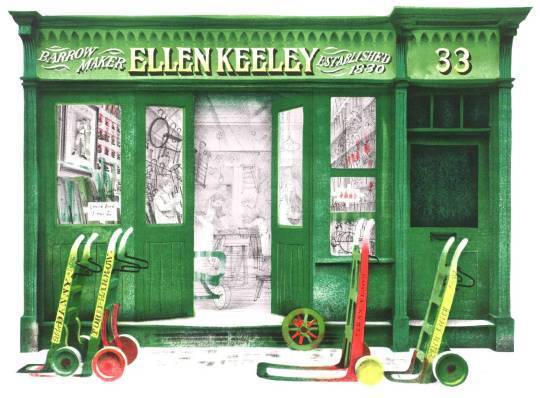

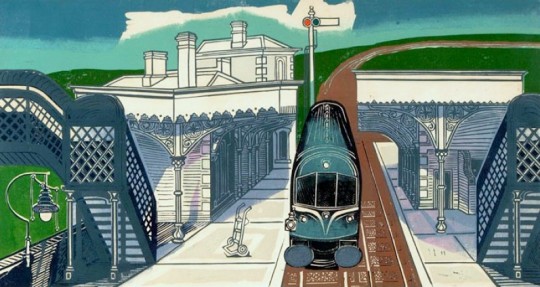

Even thought Bawden didn’t complete a print of Kings College, Cambridge, he did in the same year make a print of Braintree Station and this may have covered the commission. From one station to another, these are the main bench ends of Bawden’s world.

Edward Bawden – Braintree Station, Linocut, 1961

† BBC – Monitor, 10 November 1963

‡ Apollo Magazine – 1928, p171