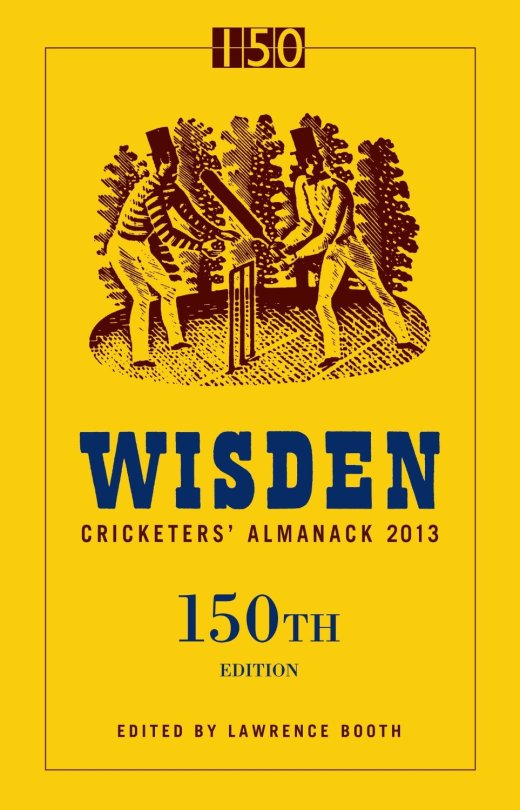

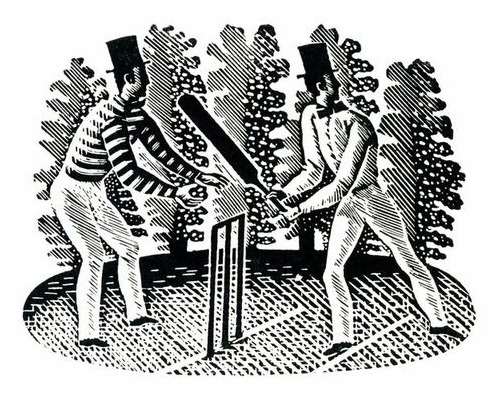

Woodcut design by Eric Ravilious by Wisden.

In 1938 typographer and spy, Robert Harling commissioned Eric Ravilious to produce an engraving for the Wisden Cricket Almanac. Harling knew Ravilious had a “special enthusiasm for the game” and wrote: “His engraving of mid-19th century batsman and wicket-keeper remains an ideal graphic introduction to one of England’s most durable publications.”

Over 75 covers have been published since 1938 with the Ravilious batsmen on the cover. The engraving briefly lost its cover-star status in 2003, when a photograph of Michael Vaughan relegated it to the spine of the book’s jacket, incurring the displeasure of traditionalists.

It was immediately restored to the cover in 2004, while staying on the spine as well. And so, for ten editions now, including this one, Ravilious’s creation has been more visible than ever.

Whatever the origin, we do know for certain that Ravilious played cricket, if at a lowly level. In 1935, he wrote of turning out for the Double Crown Club, a dining club for printers and book designers, against the village team at Castle Hedingham in Essex, where he lived for a while. He said the game went on “a bit too long for my liking and I began to get a little absent-minded in the deep field after tea”. He made one not out in defeat, and bowled a few overs. “It all felt like being back at school, especially the trestle tea with slabs of bread and butter, and that wicked-looking cheap cake.” He went on to record the comment of the Double Crown captain Francis Meynell that his bowling was “of erratic length, but promising, and that I should have been put on before. Think of the honour and glory there.”

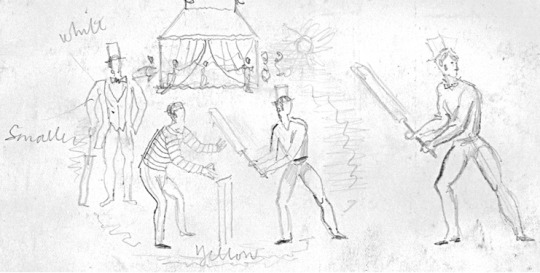

Sketch design by Ravilious for Wisden.

In another game at Castle Hedingham, with his wife Tirzah (a talented artist herself) “in charge of the strawberries and cream”, Ravilious talked of hitting three sixes. “It is, you might say, one of the pleasures of life, hitting a six.”

Ravilious saw only five of the Almanacks to carry his engraving. Yet his work — in many ways a distillation of Englishness — lives on.

John Wisden’s 187th birthday by Google doodle – 5th September 2013.

PS: Before the second world war, Robert Harling taught at the Reimann School of Design in London, where one of his pupils was the young émigré Alex Kroll, later to join him as art director on House & Garden. A keen weekend sailor, Robert took part in the wartime evacuation of British forces at Dunkirk in May 1940, which he described in his book Amateur Sailor, published in 1944 under the pen name Nicholas Drew. The poet John Masefield praised the book as the best eyewitness account of Dunkirk ever written. Robert then joined the Royal Navy, first serving on mid-Atlantic convoy duty. Again, he gave a marvellous account of this experience in his atmospheric memoir The Steep Atlantick Stream (1946).

His friend Ian Fleming was responsible for Robert’s sudden transfer from anti-submarine warfare to the newly constituted Unit 17Z, given its name by Fleming himself and headed by Donald McLachlan. This small and, to Robert, highly congenial outfit, soon to be known as Fleming’s Secret Navy, was responsible for day-to-day liaison between the naval intelligence division and the British war propaganda teams.

Secret navy assignations, involving solitary missions to the US and the far and Middle East, appealed to the cloak-and-dagger instinct in Robert. The fastidious James Lees-Milne described him as “a rough diamond”. So, to some extent, he was. Wartime experiences cemented Robert and Fleming’s mutual admiration. Robert is depicted fondly in The Spy Who Loved Me as the make-up man on the Chelsea Clarion — “a man called Harling was quite a dab hand at getting the most out of the old-fashioned type faces that were all our steam-age jobbing printers in Pimlico had in stock.”