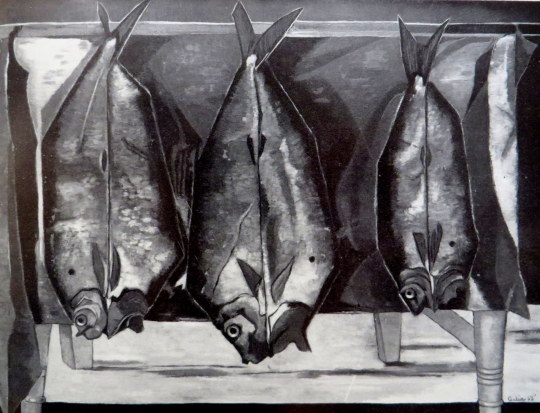

This post is about the 1967 gift of Henry Moore’s works to the Tate and how it never came to be. But more so, it’s about a public statement against that donation by 41 of his peers; people like Elisabeth Frink, Patrick Caulfield, Derek Boshier, Eduardo Paolozzi and Joe Tilson to name a few.

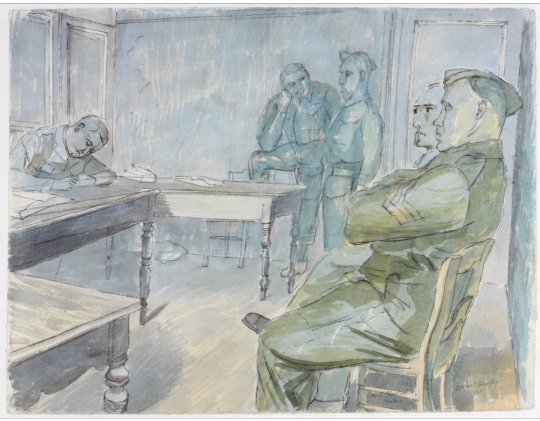

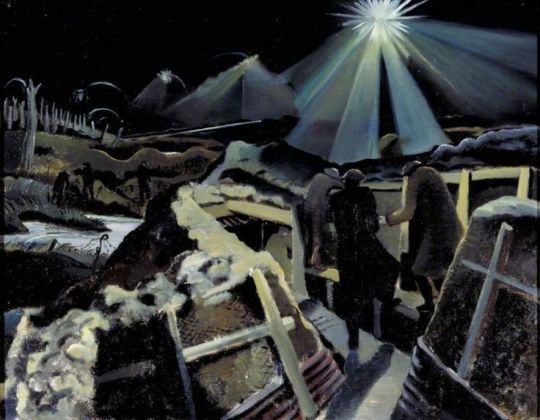

Henry Moore – Three Fates, 1941

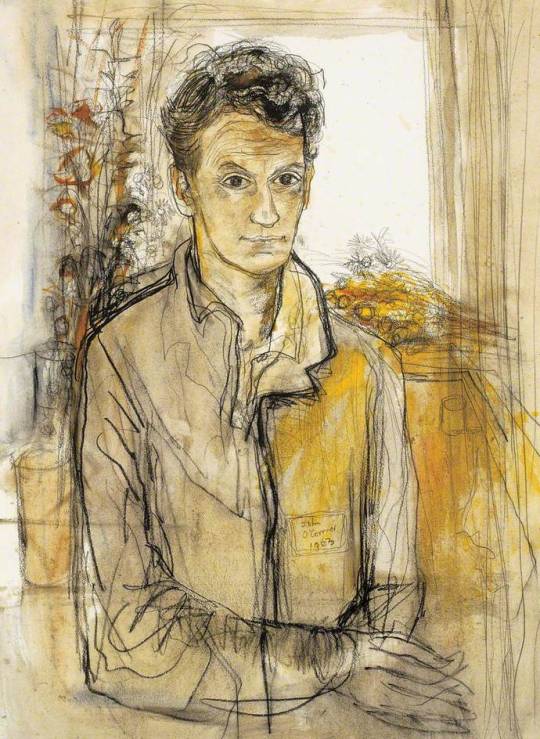

Having been a student at the Royal College of Art from 1921 to 1924, his first major breakthrough was as part of the Seven and Five Society. The society was set up in the 1920s, mostly for painters, but in the 30s they expanded and the new members bought a more abstract stance with them. The newer members where John Piper, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and John Skeaping.

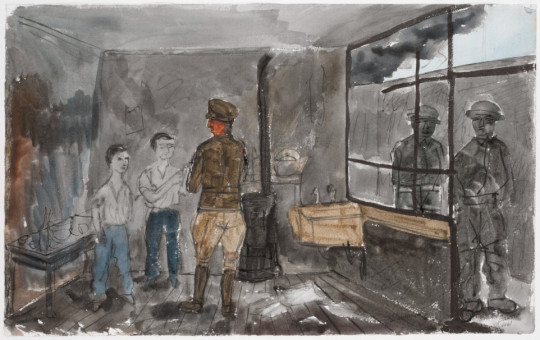

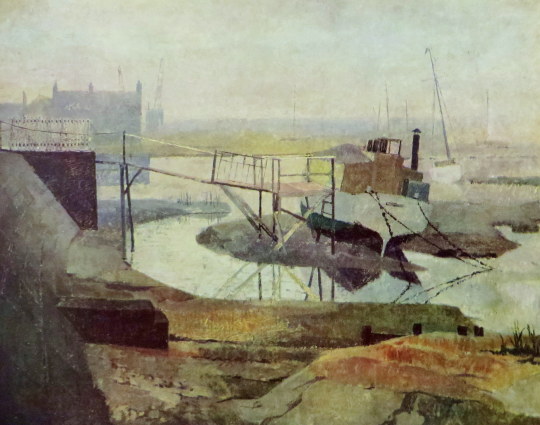

In the 40s Moore’s London Underground ‘shelter scenes’ presented his work with a human and sensitive side. From then on, a massive bulk of sculpture, drawings, paintings and books forged Moore as a great British artist.

Moore was looking how to cement his legacy as an artist. He was on, what anyone would have assumed was the peak of his forty year career.

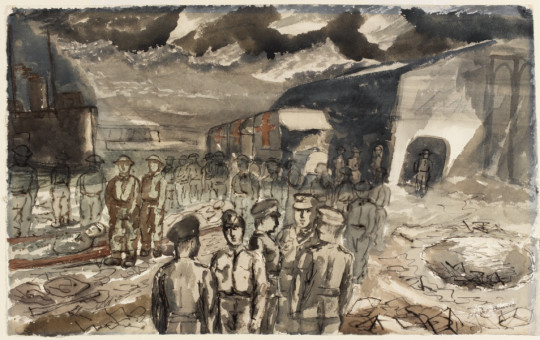

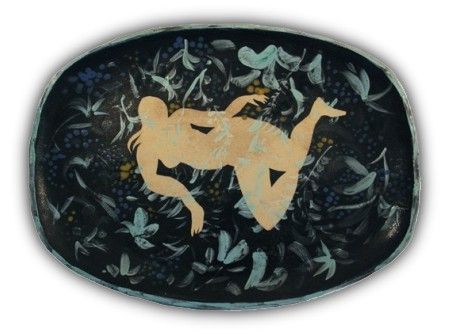

Henry Moore – Three Piece Reclining Figure No.2: Bridge Prop

On 27th February 1967, The Times’s front page hailed news that Henry Moore intended to donate many of his works to the Tate Gallery, London.

He had enjoyed a long association with the Tate, not least as trustee, and the idea of a gift was first mooted in 1964. In 1967 he made it conditional on an extension of the Tate’s galleries. †

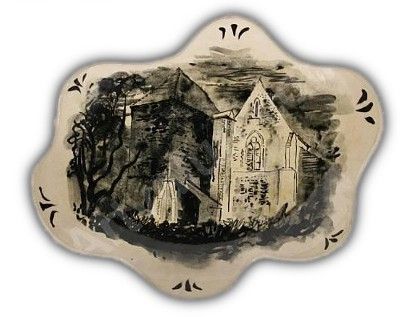

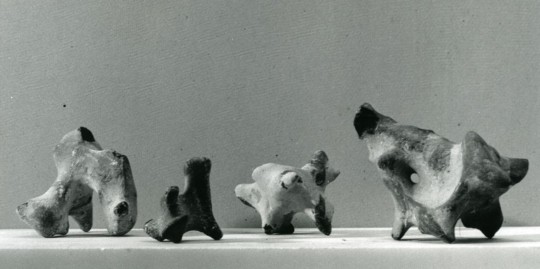

Flint stones in Henry Moore’s studio

The gift would have required the Tate to build a new wing to house the works. The cost to house the collection was rumoured to have been half a million British Pounds in 1967. In the weeks and months after the announcement, negotiations where held about how to raise the money, meanwhile, 41 artists wrote a letter to The Times to protest the new works, two of them, Moore’s own students.

The letter featured the phrase they all feared would happen if the works were housed: ‘publicly financed form of permanent enshrinement’ ‡.

‘Contemporary artists close to the Tape expressed their concern over so much space and funding going toward the celebration of one artist alone’ ♠.

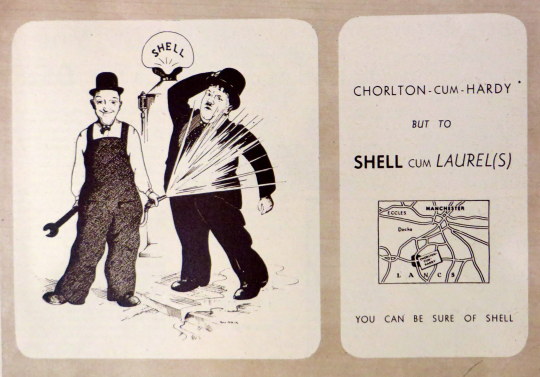

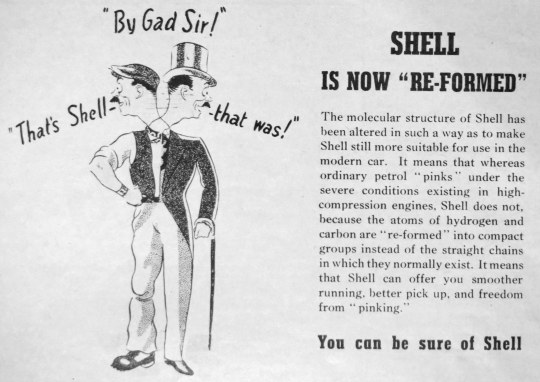

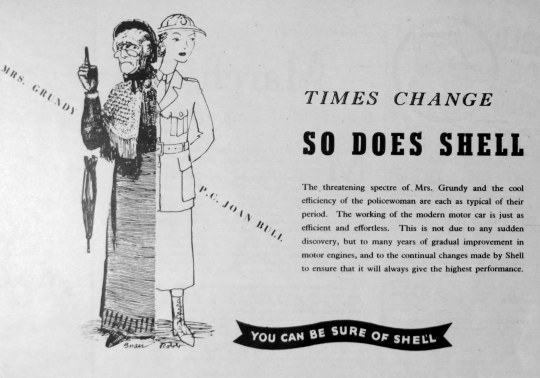

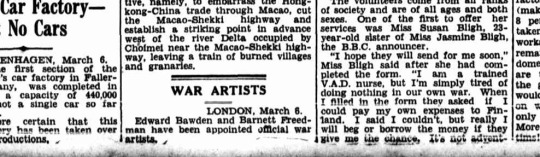

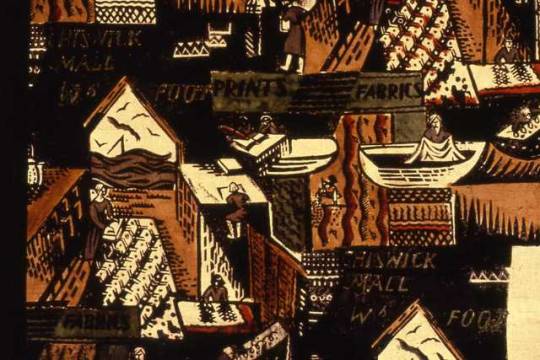

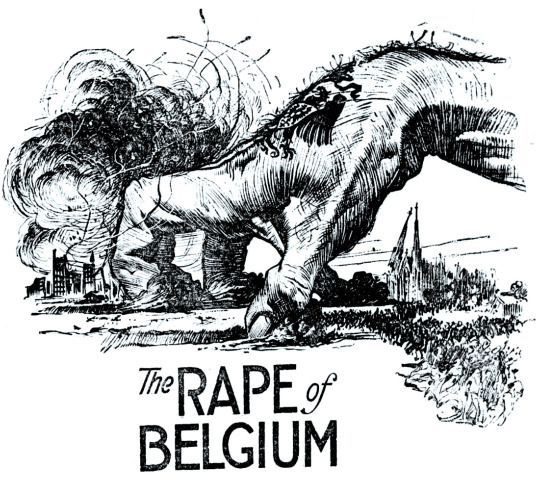

Times 26 May 1967

HENRY MOORE’S GIFT

From Mr. Craigie Aitchison and othersSir. – References have been made in the press and in public during the last few weeks concerning the offer made by Henry Moore to the Tate of between 20 and 30 major works. We understand that the Government will be giving £200,000, and that the Tate will be raising an equivalent sum specifically towards housing these works.

We must not lose sight of the fact that this £400,000, probably only a starting figure, is public money: and considering how public this whole matter should be there has been little precise information available. What can be deduced should be viewed with concern.

We may assume that at least half the gift will be large works. These alone properly displayed would require a space twice the size of the present sculpture hall. Even if the permanent display of these pieces is not envisaged the question of storage is equally crucial.

There are great priorities confronting public patronage of the arts. The Tate has only limited space into which to expand and in which to fulfil its role as the only permanent manifestation of a living culture. London has failed so far to provide itself with museum facilities commensurate with its importance as an art centre and it will not achieve its proper place as an organic part of our world by devoting itself so massively to the work of a single artist.

Whoever is picked out for this exceptional place will necessarily seem to represent the triumph of modern art in our society. The radical nature of art in the twentieth century is inconsistent with the notion of an heroic and monumental role for the artist and any attempt to predetermine greatness for an individual in a publicly financed form of permanent enshrinement is a move we as artists repudiate.

Yours faithfully,

CRAIGIE AITCHISON, DAVID ANNESLEY, GILLIAN AYRES, ANTHONY BENJAMIN, DEREK BOSHIER, ANTHONY CARO, PATRICK CAULFIELD, BERNARD COHEN, HAROLD COHEN, GARTH EVANS, SHEILA FELL, ELISABETH FRINK, PATRICK GEORGE, ANTHONY HILL, HOWARD HODGKIN, MALCOLM HUGHES, GWYTHER IRWIN, TESS JARAY, ALLAN JONES, MICHAEL KIDNER, PHILLIP KING, JOHN LATHAM, FRANCIS MORLAND, HENRY MUNDY, MYLES MURPHY, EDUARDO PAOLOZZI, JOHN PLUMB, TIM SCOTT, PETER SEDGLEY, PETER SNOW, PETER STARTUP, JOE TILSON, WILLIAM TUCKER, EUAN UGLOW, MARC VAUX, BRIAN WALL, GILLIAN WISE, ANTHONY WISHAW, BRIAN YOUNG. ‡

The works would end up going to Toronto with the art gallery there proposing to build a wing for the works and reassuring Moore with architect letters and funding plans on how they would present the collection. The galleries campaign to get the works was lead by Allan Ross, the former president of WM.Wrigley chewing gum. He stated he would donate $500,000 towards a gallery for Henry Moore in Toronto.

Ross wrote: ‘It occurred to me that we of Toronto, and Ontario, and Canada, should build a splendid classical structure to adequately house the collection you have in mind for Tate Gallery and which they for some years apparently cannot accommodate’. ♠

The Henry Moore Gallery in Toronto.

† Henry Moore by Chris Stephens, 2010. p14 9781854378767

‡ ‘Henry Moore’s Gift’, in Times 26 May 1967, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015.

♠ Sculpture and the Museum by Christopher R. Marshall, 2011. p79-80 9781409409106