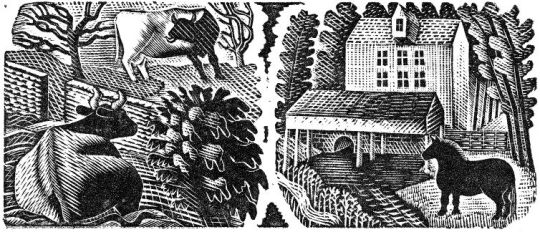

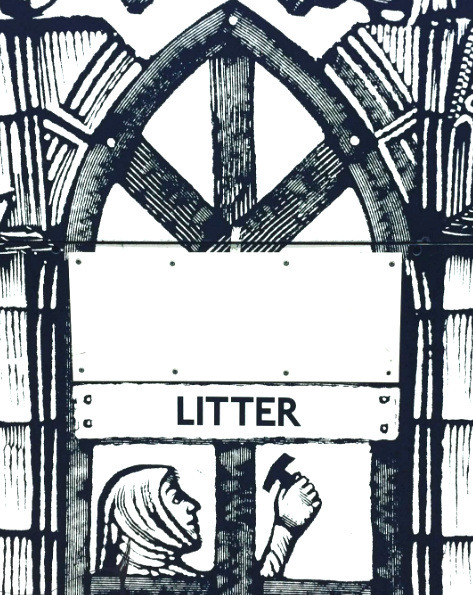

When he was commissioned to design murals for the platforms of Charing Cross underground station, artist David Gentleman (born 1930) chose as his theme the building of the medieval Charing Cross, one of the twelve memorial crosses commemorating Queen Eleanor (who died in 1290). He devised a scheme to take into account the architecture of the station, allowing spaces for entrances and exits and litter bins. He collaged together nearly 50 wood engravings which were then screen-printed onto melamine sheets by Perstorp Waterite Limited. This was the first large-scale application of wood engraving. †

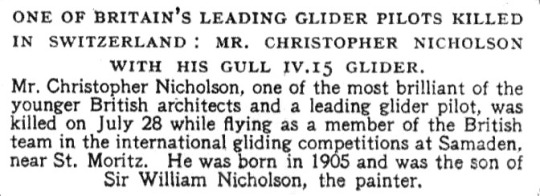

A view of the station platform when decorated in 1979.

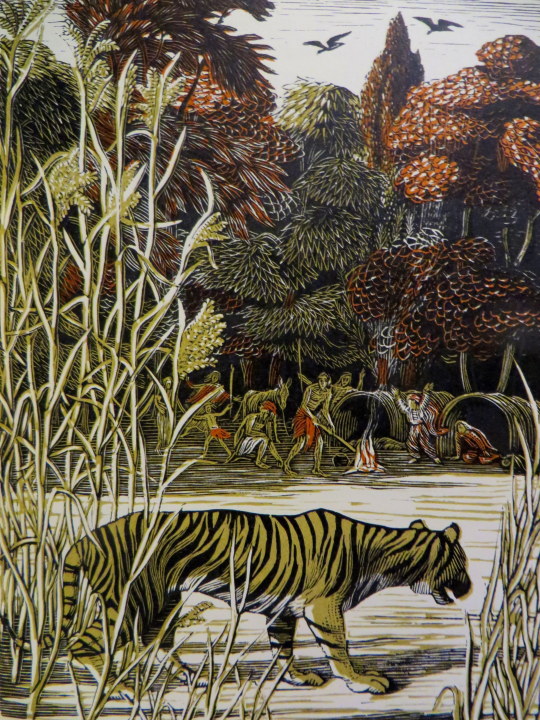

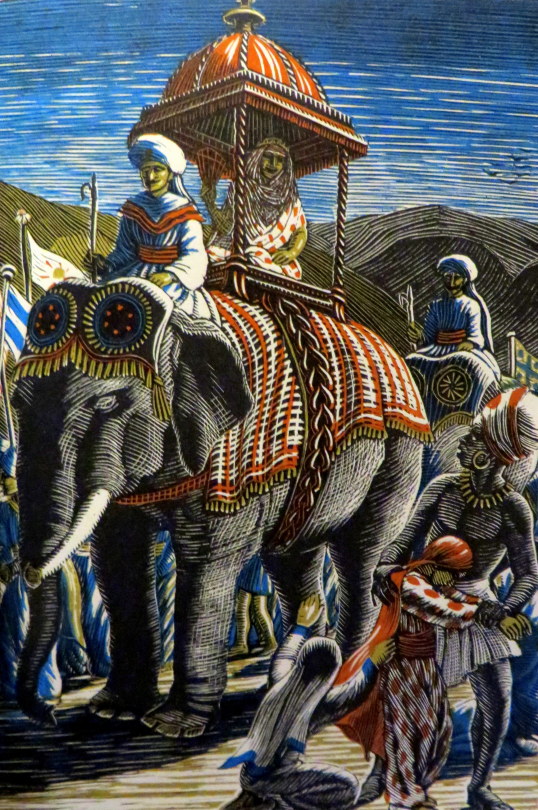

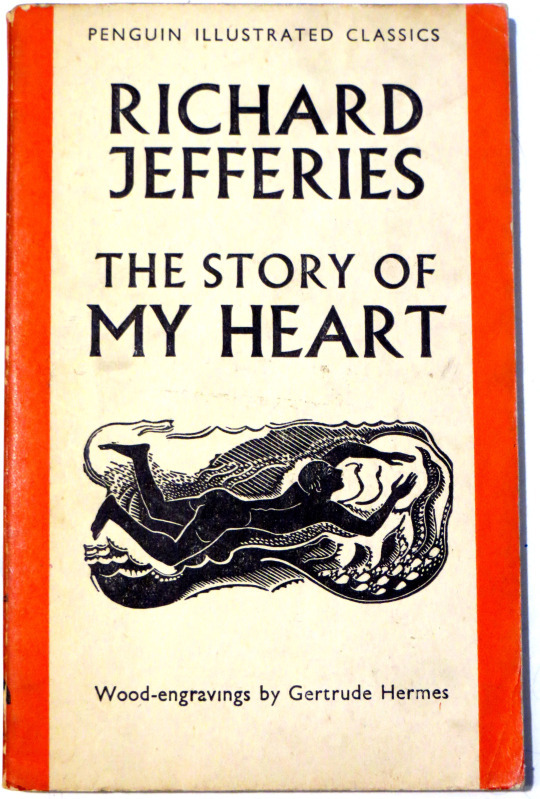

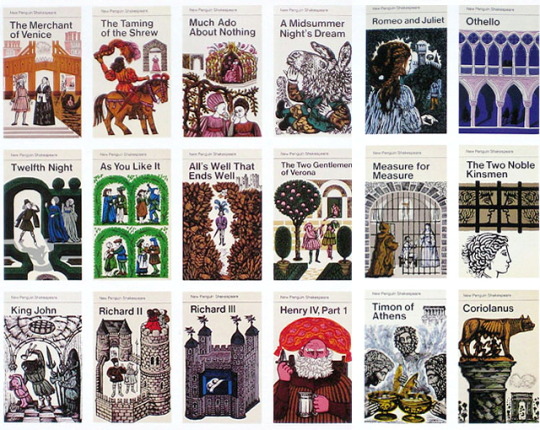

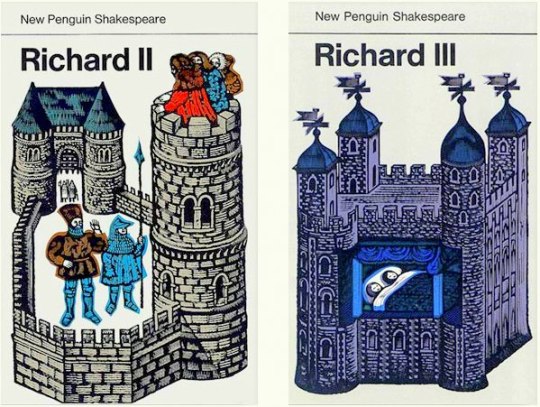

As with many works by any artist, what came before proved to be important. Before the Charing Cross commission Gentleman had been working in wood-engraving commercially for Penguin Books and their Shakespeare reprints. Steeped in a medieval theme and having to produce one image that would summarise a whole play it was useful training.

Penguin Books, Shakespeare collection with covers designed by David Gentleman.

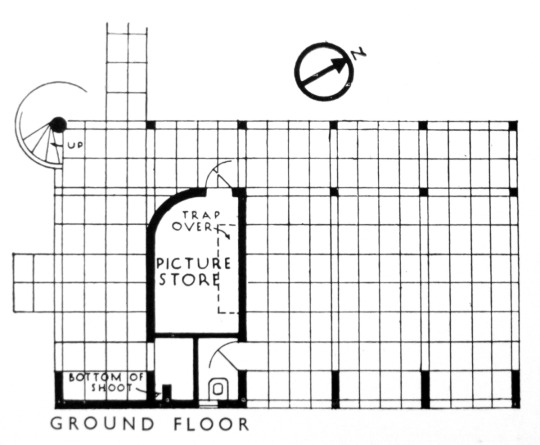

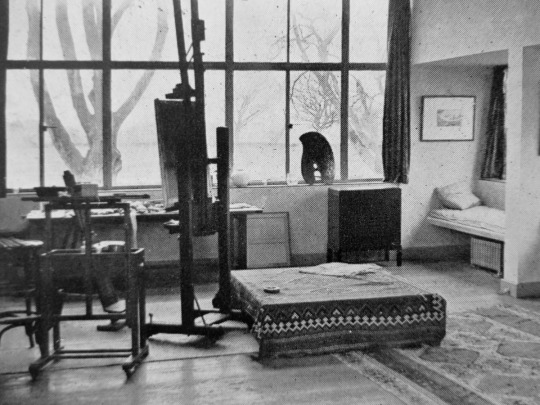

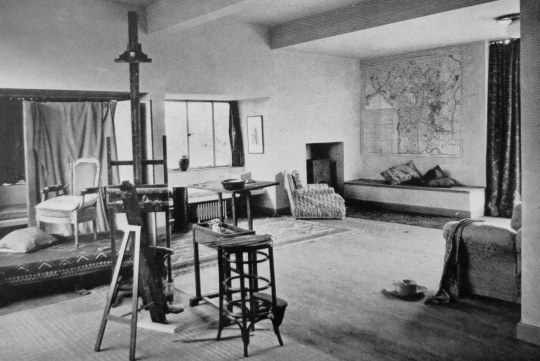

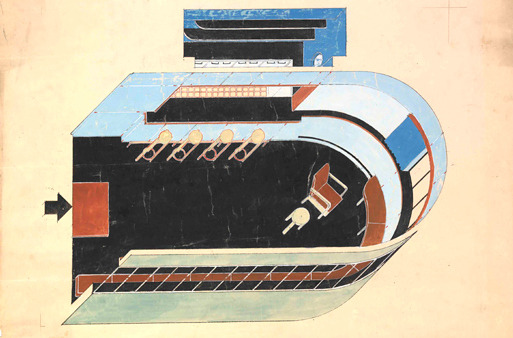

The most interesting and taxing commission to come my way so far did not begin as an engraving job at all. Late in 1977 London Transport asked me to design a mural for Charing Cross Underground station. The practical aspects were clear enough; it was to be fabricated in screen-printed melamine laminate, curved to follow the profile of the tunnel; it would be about two metres high and it would have to find room not only for numerous platform entrances and London Transport roundels but also for various staff letter boxes, telephones, plus litter bins and wooden benches for people to sit on. The subject-matter however was pretty vague. At that time the words Charing Cross suggested little more than a closed-down hospital and a run-down British Rail terminus, and the only brief was that the mural should remind passengers of what the name Charing Cross had once meant. Graphically I was given a free hand, and also the vital assurance of being directly responsible to the two people with real authority: The Chairman, Kenneth Robinson and the Chief Architect, Sidney Hardy. ‡

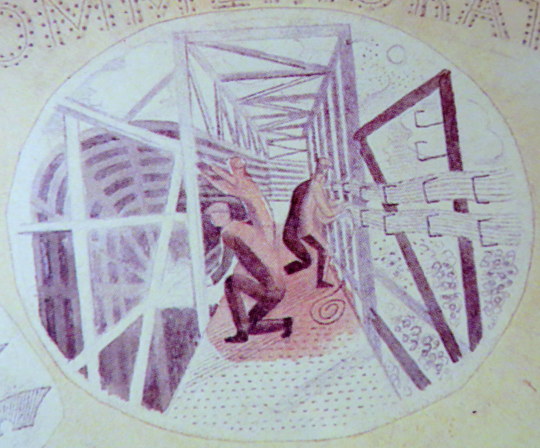

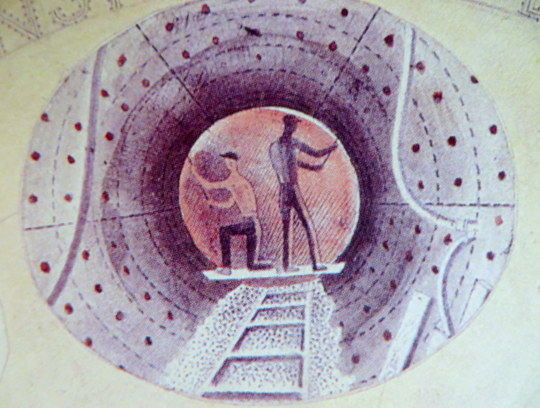

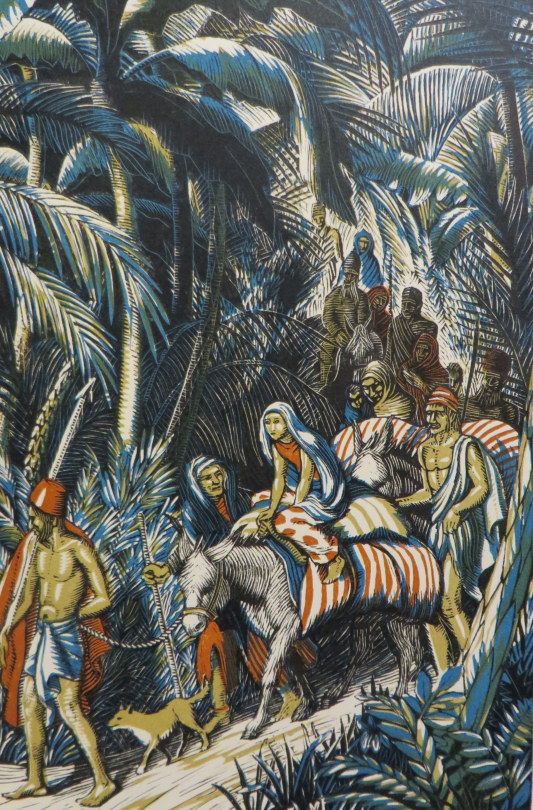

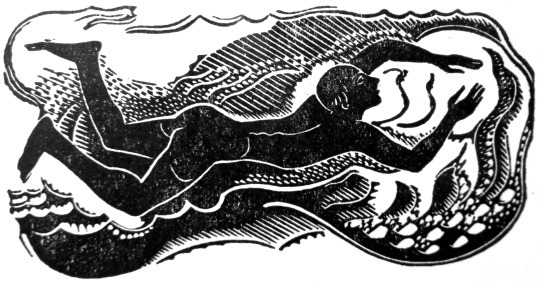

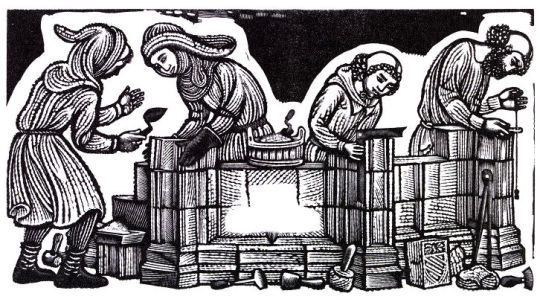

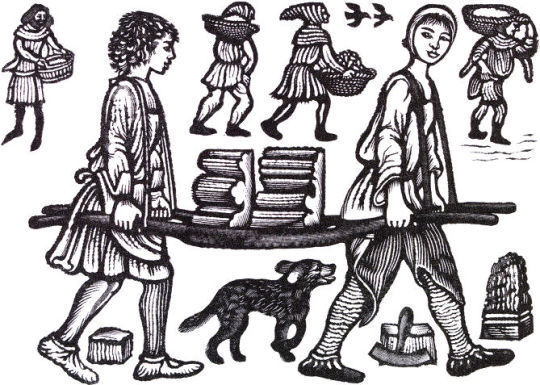

Having recently been working not only on the Shakespeare covers but also on lithographs for an American edition of The Ballards of Robin Hood, medieval imagery in illuminated manuscripts and paintings was still much in my mind, both for its epigrammatic clarity and for the way it often depicts a sequence of related events in one picture. This narrative technique suited the hundred-metre long strip of platform, and the idea of showing how the original Charing Cross had been constructed came to my mind straight away. ‡

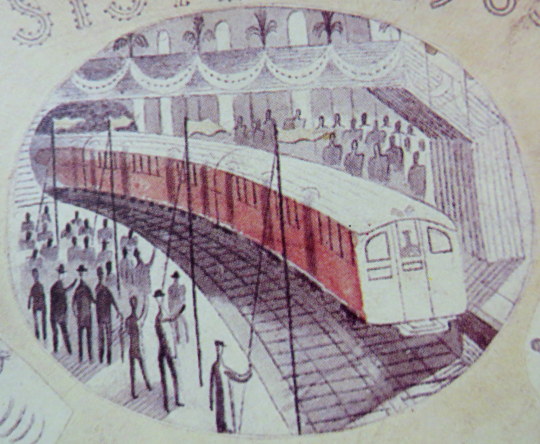

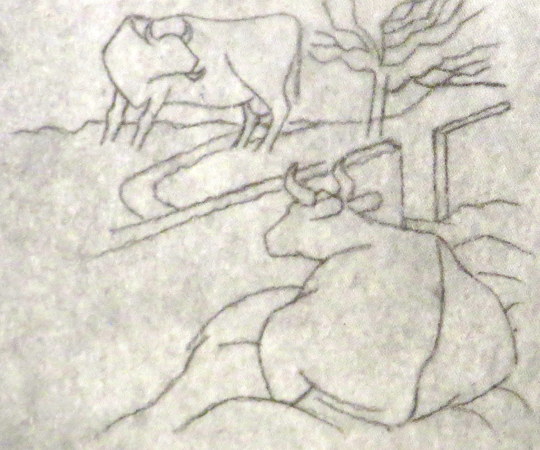

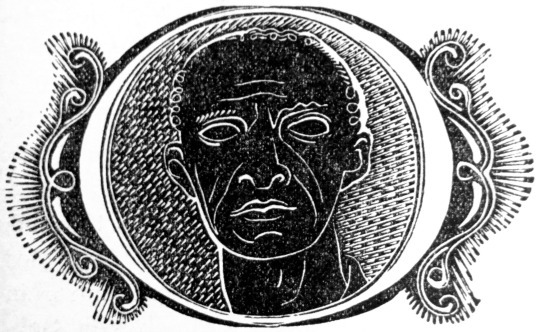

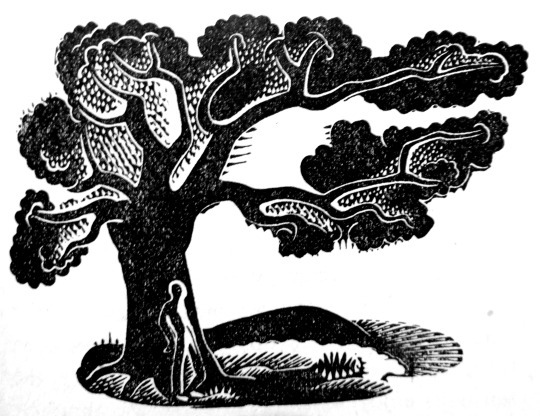

Original Woodblock by David Gentleman

Here one of the early proofs of the woodcut above for the project before the black background had been carved out.

The only proviso they made before they committed themselves absolutely to it was that a strip of it, about twenty yards long, but just as it would be finally, should be built (a mock up) in the disused Aldwych station where there are empty platforms available for such things and I got blown up (photographically) a few engravings and a few roundels… ♠

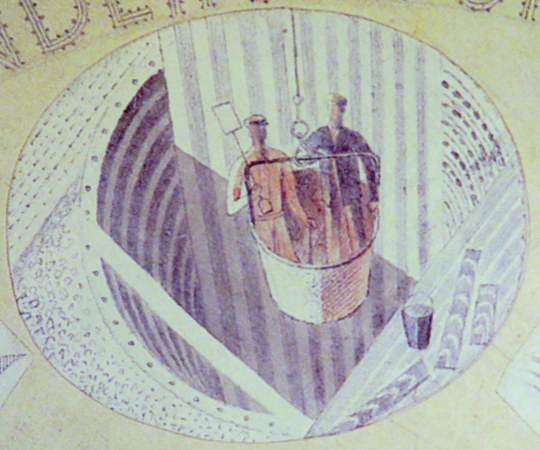

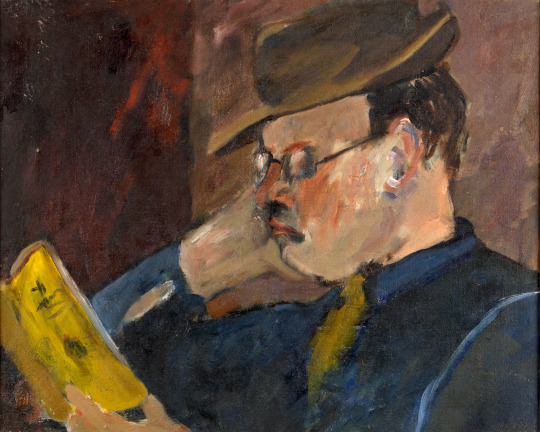

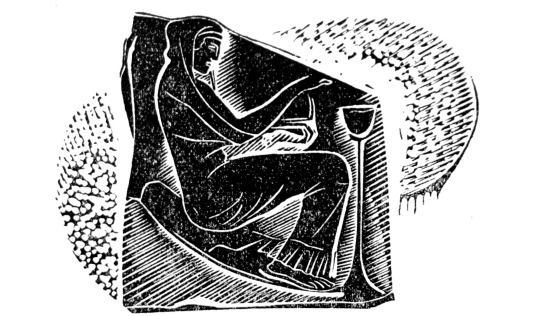

Underneath the roundel bulls-eye with ‘Charing Cross’ there was a bench where people can sit. So there was a bench built into the mock up, and then as the idea developed I got the idea that I could have the figures in my design sitting on the bench or using it as a work table. ♠

Many stations also feature unique interior designs to help passenger identification. Often these have themes of local significance. Tiling at Baker Street incorporates repetitions of Sherlock Holmes’s silhouette. Tottenham Court Road features semi-abstract mosaics by Eduardo Paolozzi representing the local music industry at Denmark Street. ♥

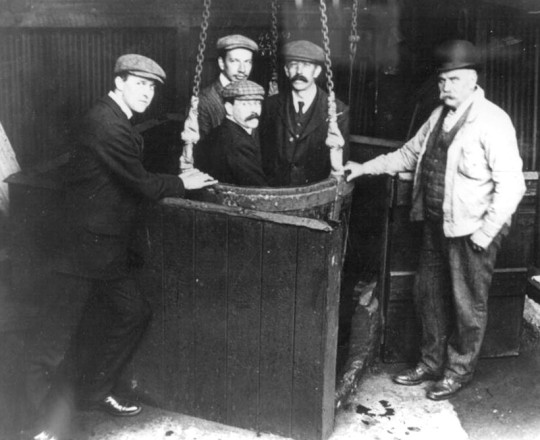

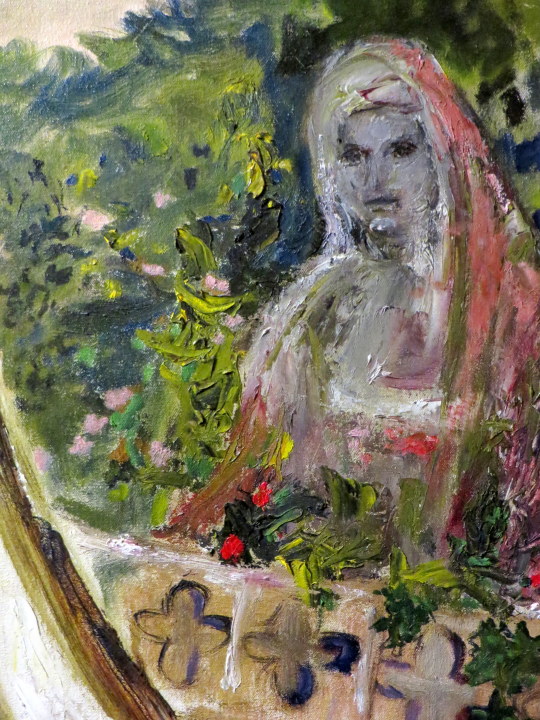

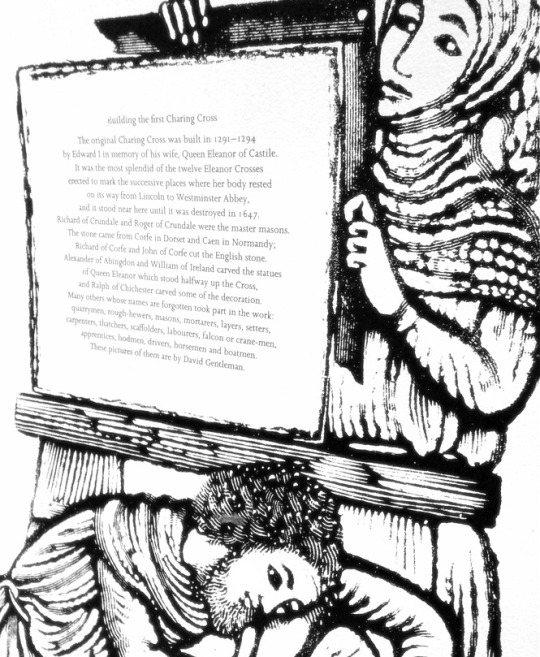

Building the first Charing Cross

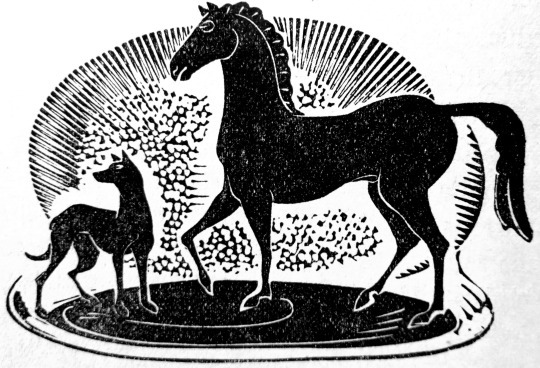

The original Charing Cross was built in 1291-1294 by Edward I in memory of his wife, Queen Eleanor of Castile. It was the most splendid of the twelve Eleanor Crosses erected to mark the successive places where her body rested on its way from Lincoln to Westminster Abbey, and stood near here until it was destroyed in 1647.Richard of Crundale and Roger of Crundale were the master masons. The stone came from Corfe in Dorset and Caen in Normandy; Richard of Corfe and John of Corfe cut the English stone. Alexander of Abingdon and William of Ireland carved the statues of Queen Eleanor which stood halfway up the Cross, and Ralph of Chichester carved some of the decoration. Many others whose names are forgotten took part in the work: quarry-men, rough-hewers, masons, mortarers, layers, setters, carpenters, thatchers, scaffolders, labourers, falcon or crane-men, apprentices, hodmen, drivers, horsemen and boatmen. These pictures of them are by David Gentleman ♣

The historical plaque with the text (above) and the enlarged wood engravings by David Gentleman.

† David Gentleman – V&A Website.

‡ The Wood Engravings of David Gentleman, David Esslemont p114, 2000.

♠ Oral History – David Gentleman – Reel 4, Imperial War Museum, 2008-07-03.

♥ London Underground – An overview. Pediapress

♣ Mural text in Charing Cross Station, London.

Guide to the Archive of Art and Design, Victoria & Albert Museum by Elizabeth Lomas, 2001.