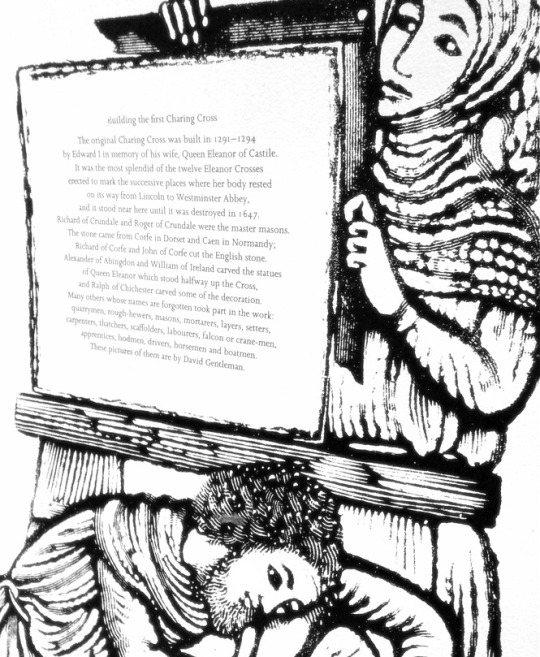

In 1940 Eric Ravilious became one of the first official war artists. During the summer he was posted to HMS ‘Dolphin’ in Gosport, drawing the interiors of submarines and sometimes sent out to sea. He had already conceived the idea of a set of submarine lithographs intended as a children’s painting book, and in November he set to work.

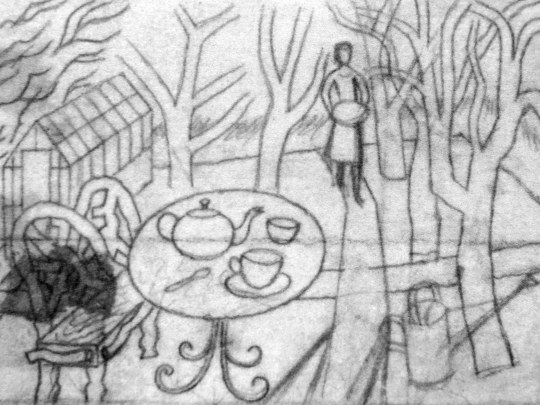

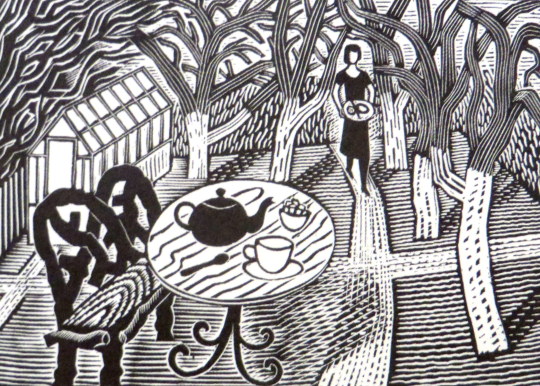

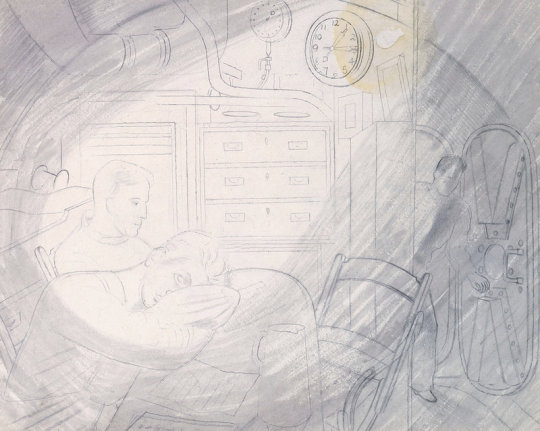

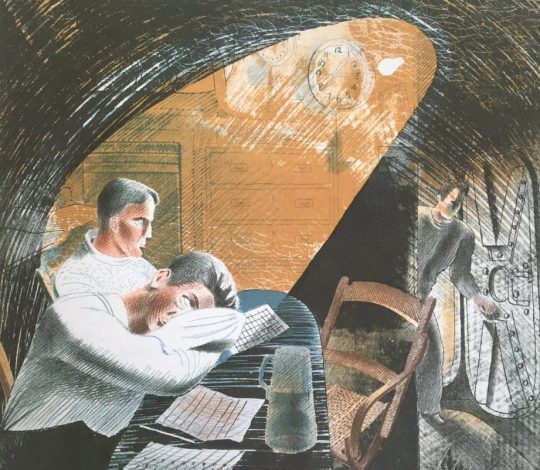

The drawings inevitably lack the distinctive texture and colour of the lithographs. In this post they are set next to the finished lithographs with the colours and textures produced at W. S. Cowell Ltd over the original drawn and watercoloured pictures by Ravilious. But we must start first with his appointment as a war artist:

Eric Ravilious – Drawing for Commander and Periscope, 1941

Dear Ravilious, 23rd December, 1939

You may have heard rumours of a scheme which is now being launched for having various phases of the war recorded by selected artists working for the Government. The Admiralty has already appointed one official whole-time artist, and you and John Nash have been selected to work for the Admiralty on a part-time basis, if you should be willing. We very much hope that the idea will appeal to you; indeed it would be a great disappointment to the Admiralty, the Ministry of Information, and, I may add, myself, if you should feel unable or unwilling to undertake work of this kind.If you should be willing, please let me know here as soon as you can and tell me when you could come and see me to discuss details. From our point of view, the sooner you get to work the better. Perhaps I should say that the Treasury have already approved the necessary expenditure.

Yours sincerely

R. Gleadowe †

During World War II Reginald Gleadowe was an Admiralty representative on the War Artists’ Advisory Committee.

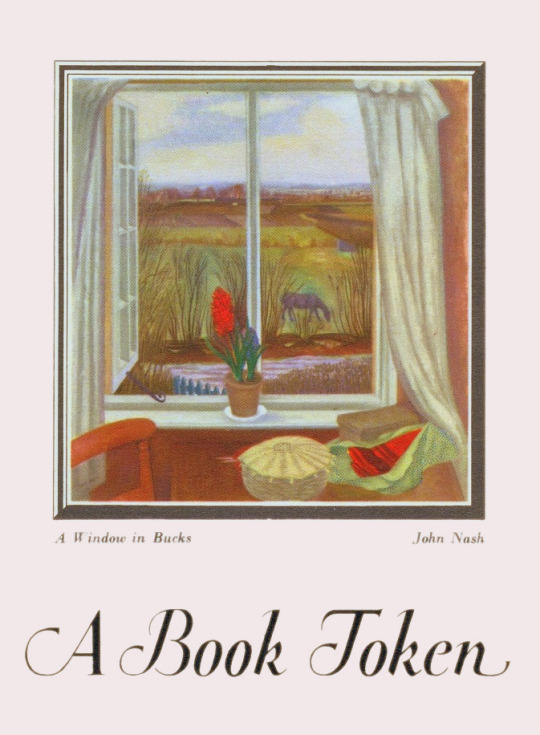

Below is a letter from fellow artist (and Ravilious’s tutor) John Nash. Nash had been a war artist in the First World War found himself being asked to become a war artist again.

My dear Eric,

I was at the M.of l. (Ministry of Information) on Friday playing truant part of the time from College and heard from Dickey that you had been there. I don’t suppose I have anything more to report than you have they talk of sending us a ‘contract letter’ but that only deals with the finance and I have heard nothing from the Admiralty since I went there. When I was there I broached the subject of commissioned rank to Gleadowe and there seemed no difficulties. Captainships seemed as cheap as farthing buns and it seemed as if one only missed being made a Major because one had to recognize Muirhead Bone’s seniority! But I begin to doubt now if Gleadowe really has the authority to promise these insignia – we must continue to wait and see I suppose… .

I went to College yesterday and saw most of ‘the boys’. Form was good or even above average and Percy [Horton] made a fine story of a week spent teaching the Punch artist H. M. Bateman to paint. Dickey tells me that the Army War Artists are to be dressed in War Correspondents’ uniform with W.C. on the hat band rather shaming so I’m glad you and l are in the Senior Service!Let me know if you hear anything fresh.

Yours ever,

John †

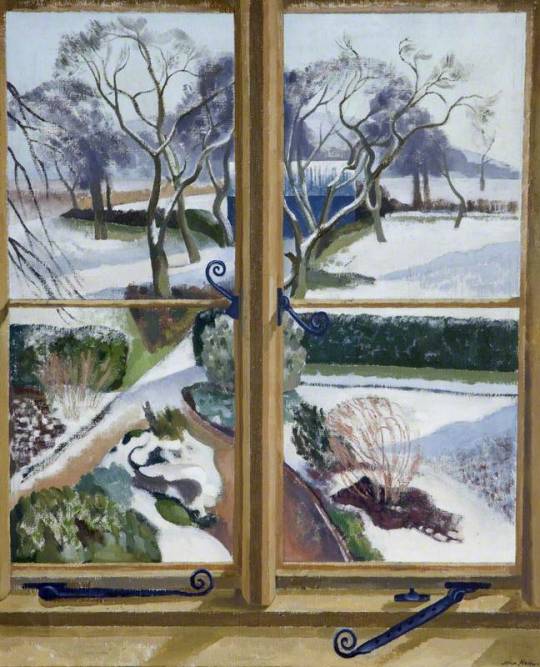

It is fitting that they both should be chosen so early for this as a lot of the work for both of them was to be painting docks and the boats. Below are paintings each by Ravilious and Nash. They had got to know each other at the Royal College of Art, where Ravilious was a pupil and now they were both on the staff. A year before Gleadowe’s invitation, and on Nash’s recommendation they both went to sketch at Bristol Docks. They painted the same location at night, when the docks were quiet and the boats tied up.

John Nash had been much inspired by painting in Bristol, and he told Eric it was the best port in England, so they planned together a painting visit there. †

Eric Ravilious – Bristol Docks, 1938

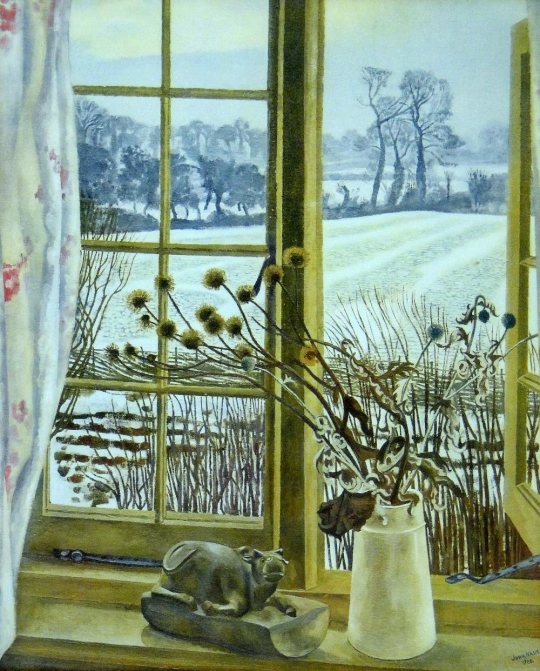

John Nash – Nocturne: Bristol Docks’, November 1938

The Second World War, unlike the First, was not much recorded by printmakers and the Ravilious Submarine series, perhaps the most important such work, was eventually turned down for publication by the Artists Advisory Committee. ‡

The difference of print-making in WW1 and painting in WW2 was that in WW2 the Blitz brought the war to the artists, they could see defences, barrage balloons and blitz bomb damage while still in Britain and record it with most of their materials at hand. The paintings and drawings were recorded quickly as a reaction. In contrast to the prints made in WW1 mostly depicted life in France and Belgium on the front-lines. Works would have to be sketched out and when back in Britain, the prints made from memory and worked up from sketchbook studies for a wider publication. The bridge of a month would mean that the art of WW1 was already retrospective of conditions. People living in the south of England would have been aware of defences, blacked out road signs, and the blitz.

Much of what we know from the process of the lithographic Submarine series comes from letters sent to Dickey (Edward Montgomery O’Rorke Dickey.) At the beginning of the Second World War ‘Dickey’ was seconded from the Ministry of Information and, from 1939 to 1942, was secretary of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee. He was a full member of the committee from 1942 to 1945. During this period he established his close relationship with Eric Ravilious.

Bank House, Castle Hedingham, Essex 24th January 1940.

Dear Dickey,

The Curwen Press have sent me an estimate for the lithographs I spoke to you about – to do six, in five workings each about 15″ x 22″ will cost £36. This seems reasonable to me, if your committee think the idea a good one. Paints and materials will bring the total expenses to, say, £40; so that the choice is actually between £4 or £40, whatever they feel inclined to do. I very much want to do some lithography if that is possible, also it will make a change of medium. Will they call on us to begin work soon, do you think? It is now I see just a month today since the Admiralty wrote about this appointment, and nothing more seems to have happened since then. ♠

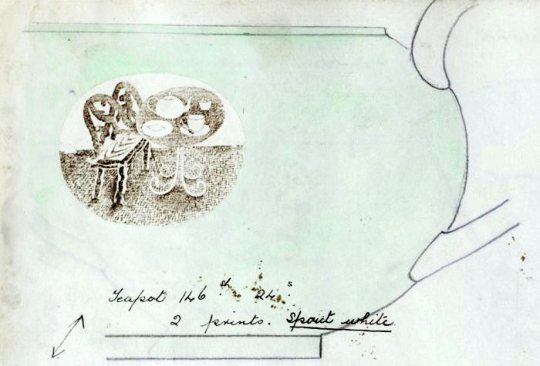

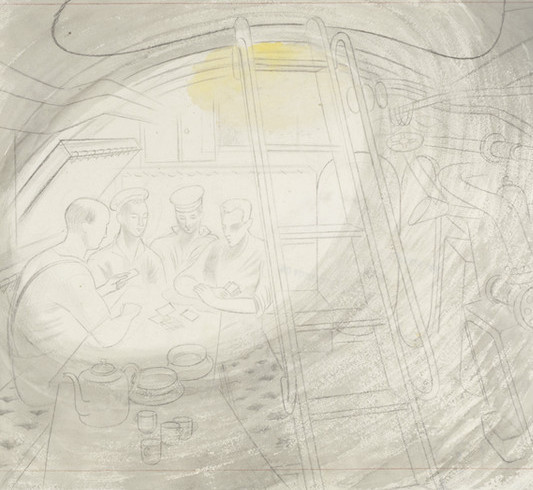

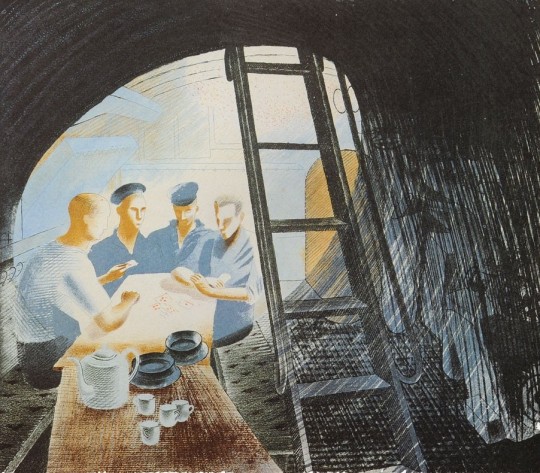

Eric Ravilious – Study for Ward Room #1, Pencil and Watercolour, 1941

Eric Ravilious – Ward Room #1, Lithograph, 1941

HMS Dolphin, Gosport, Hans. 2nd August 1940.

…At the moment I am living here having been to sea at different times for the last two weeks in the submarine, trying to draw interiors. Some of them may be successful I hope, but conditions are difficult for work. It is awfully hot below when they dive and every compartment small and full of people at work. However this is a change from destroyers and I enjoy the state of complete calm after the North Sea – there is no roll or movement at all in submarines, which is one condition in their favour, apart from the smell, the heat and noise. The scene is extraordinarily good in a gloomy way. There are small coloured lights about the place and the complexity of a Swiss clock…♠

Eric Ravilious – Study for Ward Room #2, Pencil and Watercolour, 1941

Eric Ravilious – Ward Room #2, Lithograph, 1941

Dear Dickey

…Neither Curwen, Ripley, Murray or Lane can produce these submarine pictures, for all sorts of reasons, so I’ve not abandoned the idea of a book and yesterday went to see the lithographic printers at Ipswich. They will produce the things simply as pictures in a small edition for £100; and if I can manage it this shall be done…

The Leicester Gallery say that they are willing to sell the lithographs if I produce them, so that with luck (if they are not bombed meanwhile) it may pay the expenses. ♣

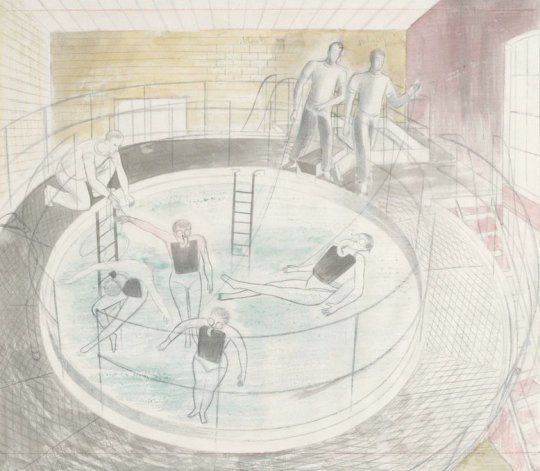

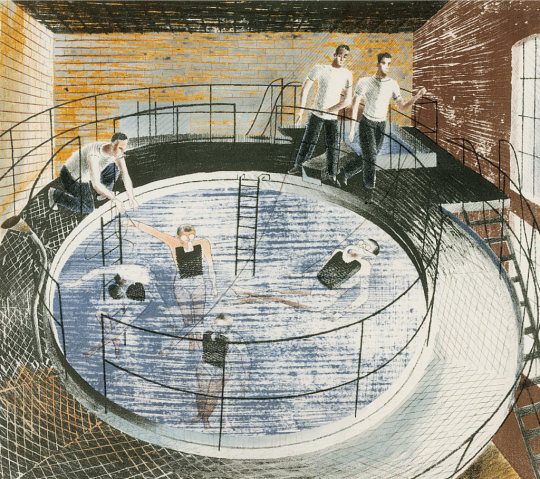

Eric Ravilious – Testing Davis Equipment, Pencil and Watercolour, 1941

Eric Ravilious – Testing Davis Equipment, Lithograph, 1941

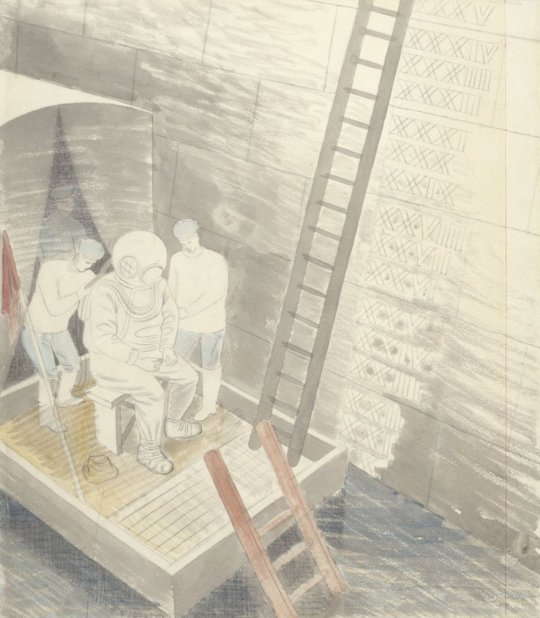

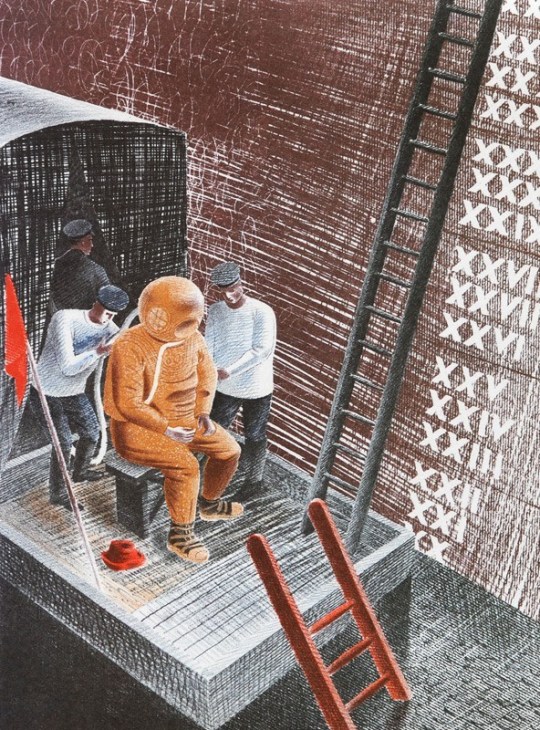

Eric Ravilious – The Diver, Pencil and Watercolour, 1941

Eric Ravilious – The Diver, Lithograph, 1941

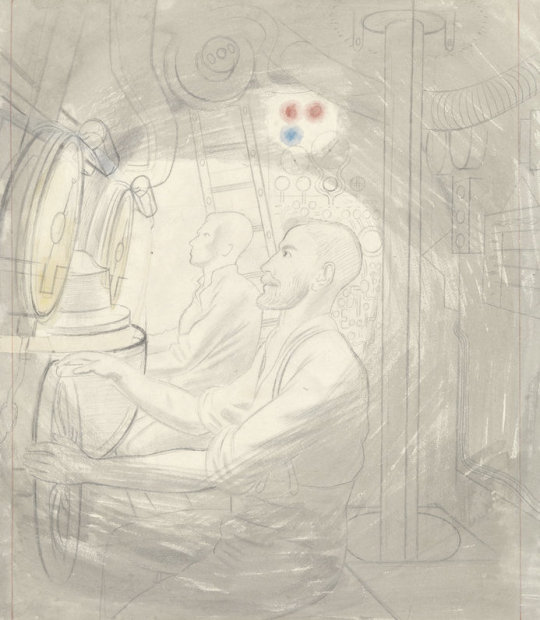

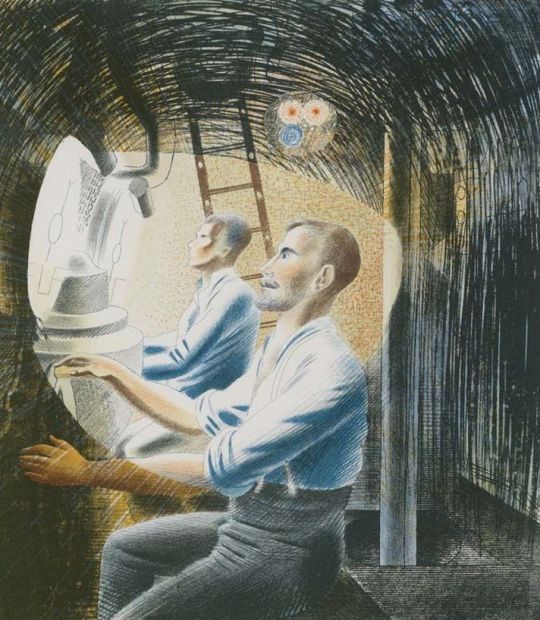

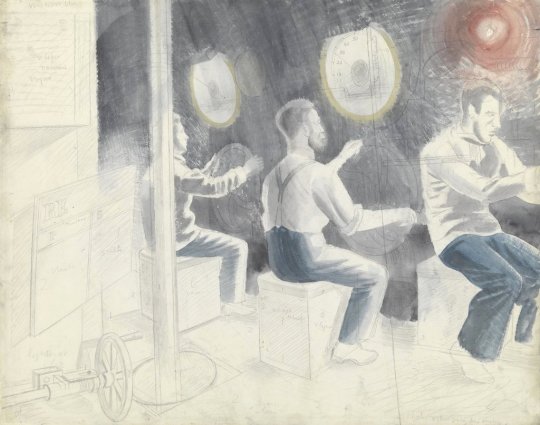

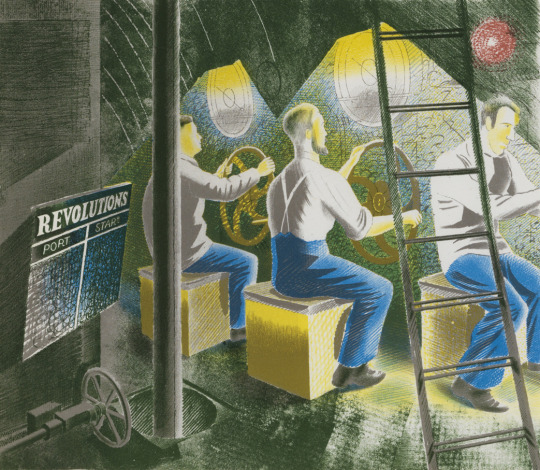

Eric Ravilious – Working Controls While Submerged, Pencil and Watercolour, 1941

Eric Ravilious – Working Controls While Submerged, Lithograph, 1941

Eric Ravilious – Diving Controls #2, Pencil and Watercolour, 1941

Eric Ravilious – Diving Controls #2, Lithograph, 1941

The final lithographs were printed in a small run in 1941. In 1996 a limited edition reprinting of 375 was made. Ravilious died in 1942, he was reported missing, presumed dead while on flight over Iceland. He was 39 years of age.

Eric Ravilious – Commander and Periscope, Pencil and Watercolour, 1941

Eric Ravilious – Commander and Periscope, Lithograph, 1941

Had Ravilious’s idea of a children’s book proceeded it is hard to tell if it would have been just outlines of the men and nautical instruments or with the base watercolour and pencil drawings that he used for the lithographs. Either-way a child could paint over with their own colours. That is really what the printers at

W. S. Cowell Ltd did with the lithographs anyway.

† Eric Ravilious: Memoir of an Artist – By Helen Binyon

‡ The Modern Spirit in British Printmaking, 1910-1950. Garton & Cooke, 1987

♠ Submarine Dream – Lithographs and Letters – The Camberwell Press, 1996

♣ Avant-garde British printmaking, 1914-1960