Before television, the radio was the main media for the nation. The British Broadcasting Corporation was free from advertising and their early aims were to ‘educate, inform and entertain’. It was the education element that lead to leaflets being produced as a visual aid to the radio. The public could send a stamped-addressed envelope off and receive guide to the content in the radio show, from photographs of master paintings as part of a series of lectures on art to song sheets.

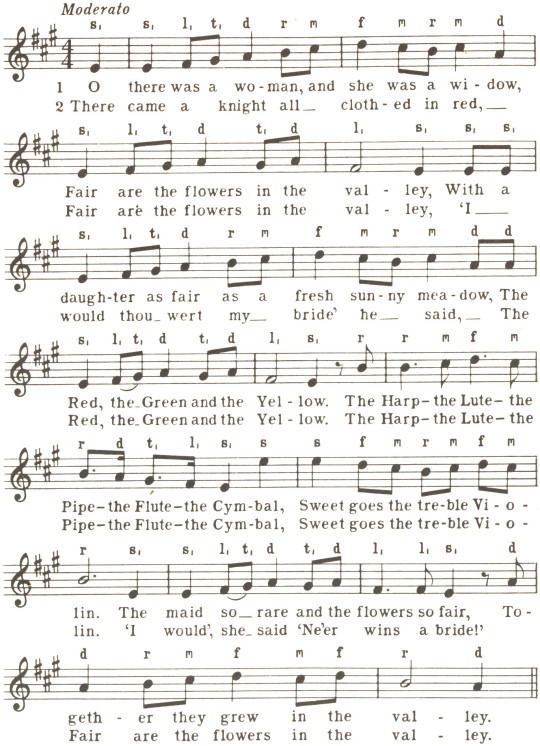

All of the artists from the Great Bardfield group would at one time or another work as commercial artists, many illustrating books. Here is a selection of works made for the BBC.

Eric Ravilious – BBC Talks Pamphlet, 1934

Published in 1934 this booklet was to follow six lectures on art, there are seven pages of text and 30 pages of black and white illustrations. The cover design is a wood engraving by Eric Ravilious showing a Bewick style wood-engraving, an artists pallet and oil paints and some beautiful graphic devices hand carved around the vignette. This booklet could be bought as a softback at seven pence or a hardback at one shilling.

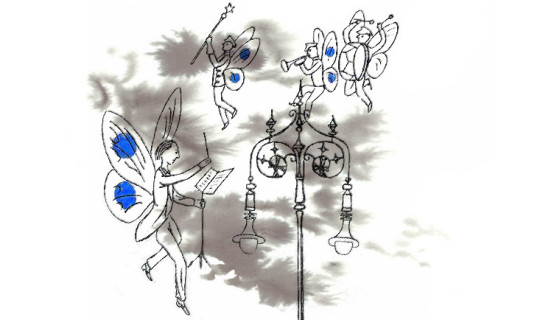

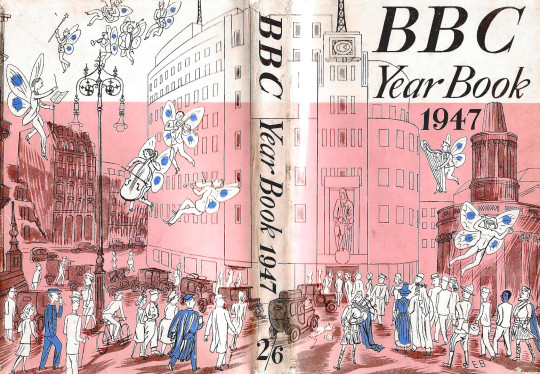

Edward Bawden – Dust Jacket for the BBC Year Book 1947

This cover by Edward Bawden shows Broadcasting House and All Souls Church with musical faeries flying around. The BBC Year book started as an annual review beginning 1928. In the mid 50′s it became the BBC Handbook and in the 80s merged into an Annual Report. The focus of the publication would range from statistics of people with Radio Licences, to essays on Opera, Art and even Foley House, the building that Broadcasting House replaced. But this gives me a wonderful excuse to share a picture of this magnificent building so you can compare it to Bawden’s drawing.

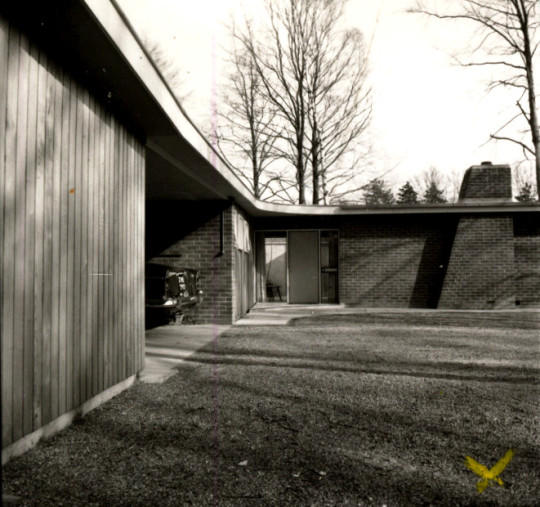

BBC Broadcasting House, London, 1932.

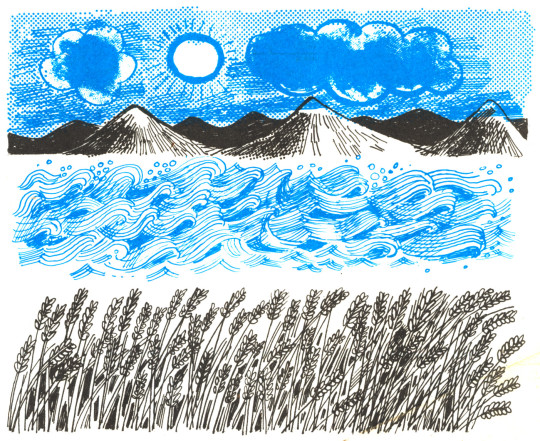

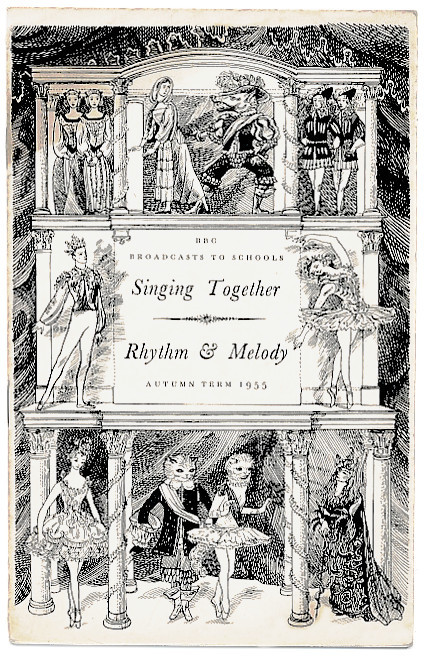

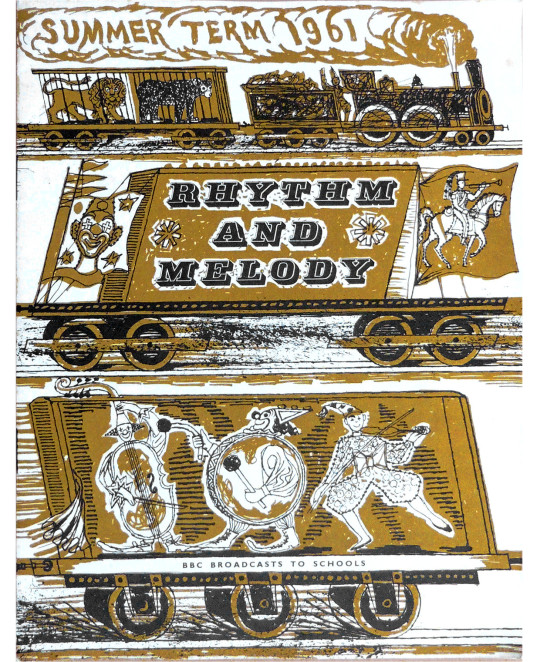

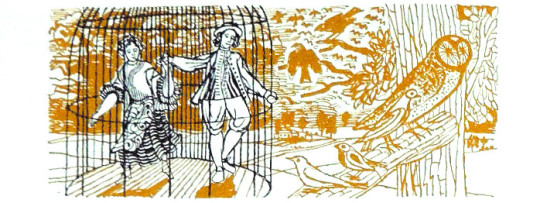

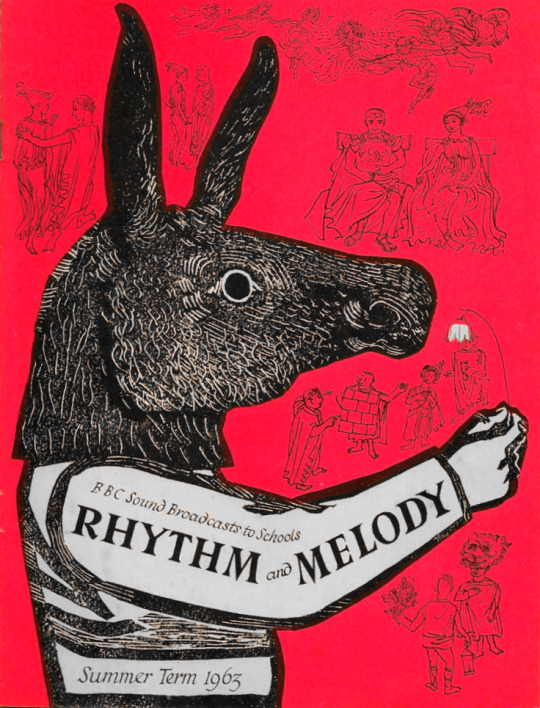

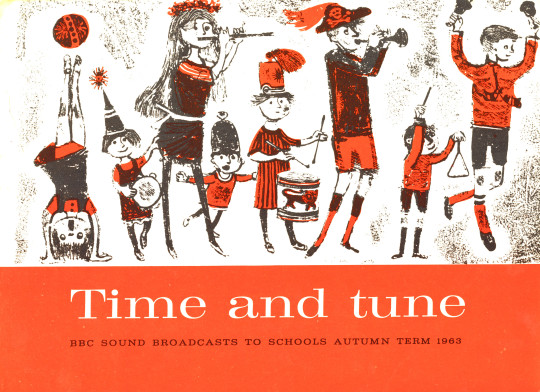

Many of the other works in the rest of this article are simple two colour illustrations made for various children’s educational radio programs. The way each of the artists went about solving this problem is interesting but mostly it is based on technique and time. Inside the covers is usually sheet music, lyrics and an illustration for most of the songs.

Many of Shelia Robinson’s illustrations are black and white pen drawings or her cardboard-prints, but rarely is there much colour and when there is it looks to be the printer flooding the image around her illustration with it. It’s a shame because her art prints are extraordinarily competent.

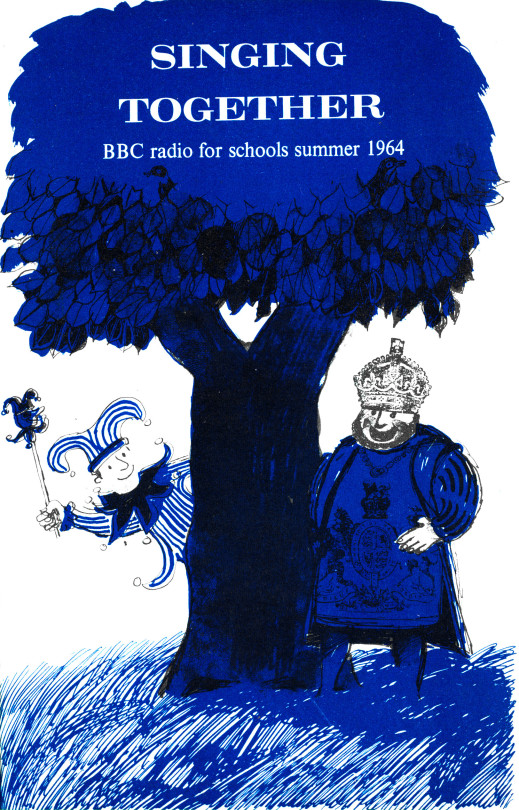

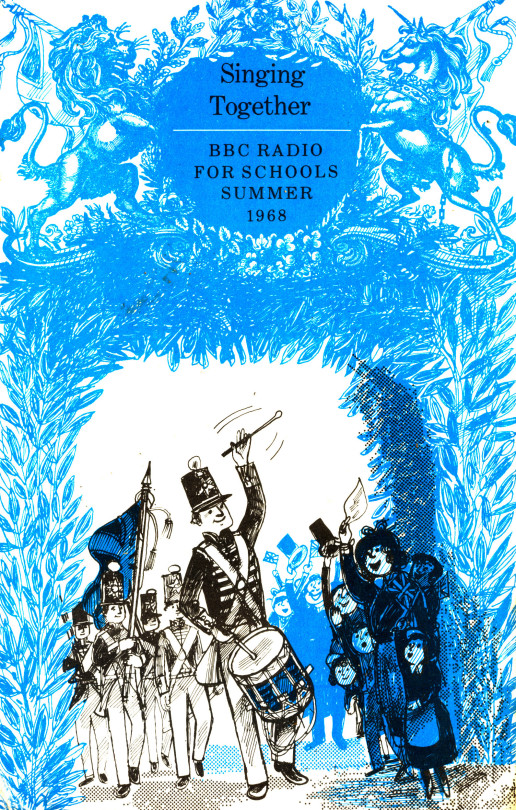

Bernard Cheese’s works have a more interesting use of colour and layering for those interested in printmaking and use of one colour with black, as is the work of Walter Hoyle.

Sheila Robinson – Sing Together – Rhythm & Melody, 1955

Walter Hoyle – Rhythm and Melody, 1961

Walter Hoyle – Illustration from Rhythm and Melody, 1961

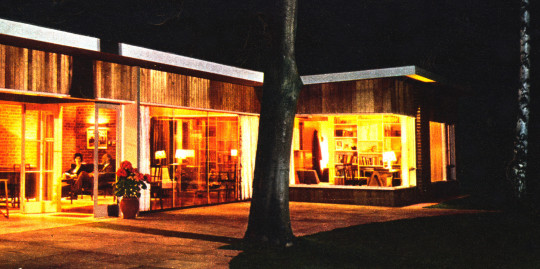

Sheila Robinson – Singing Together, 1961

Sheila Robinson – Rhythm and Melody – Summer, 1963

Bernard Cheese – Time and Tune, 1963

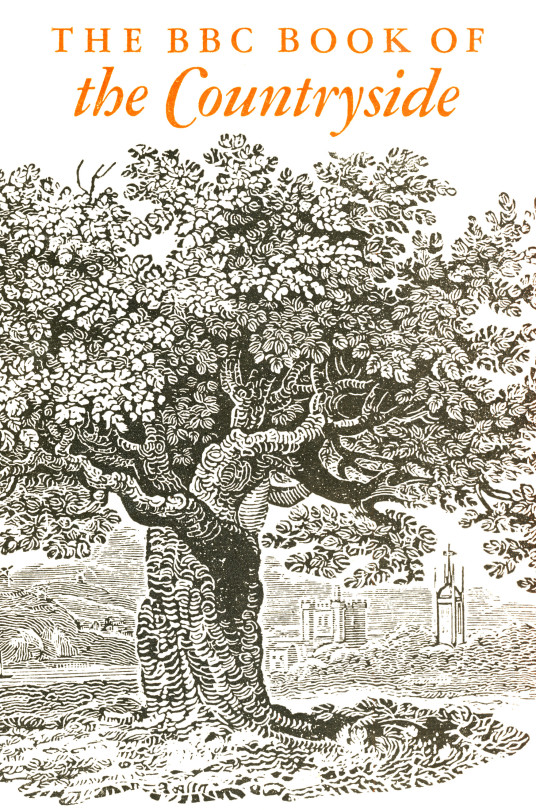

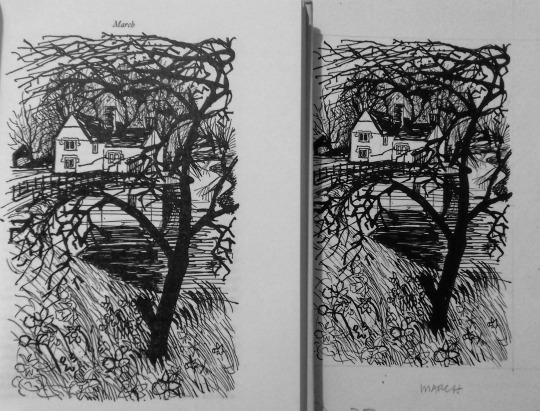

In a break from BBC radio pamphlets comes the BBC Book of the Countryside. A hardback book with a compilation of the BBC Countryside programs set out in a month by month calendar. For fans of Great Bardfield and East Anglian art, one gets work by both Walter Hoyle and Sheila Robinson, but also six illustrations by John Nash. The drawings from the book by Walter Hoyle I am delighted to own as part of my collection.

Cover to the BBC Book of the Countryside, 1963

Walter Hoyle – Page from the Book of the Countryside to the left and the drawing to the right, 1963.

Sheila Robinson – January, 1963, illustration from BBC Book of the Countryside

Walter Hoyle – April, 1963, illustration from BBC Book of the Countryside

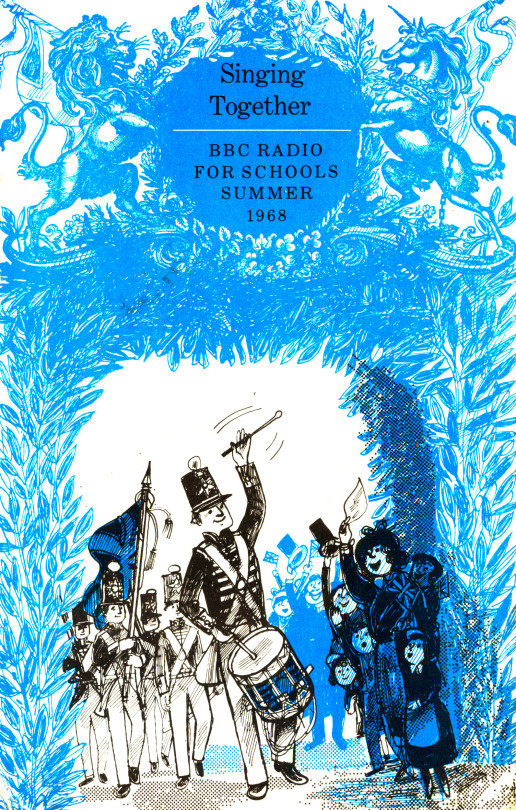

Bernard Cheese – Singing Together, 1964

Bernard Cheese – Singing Together, 1968

Bernard Cheese – Illustration from Singing Together, 1968

To see more illustrations from the Bernard Cheese Singing Together 1968 book, click here as I dedicated a full post to them