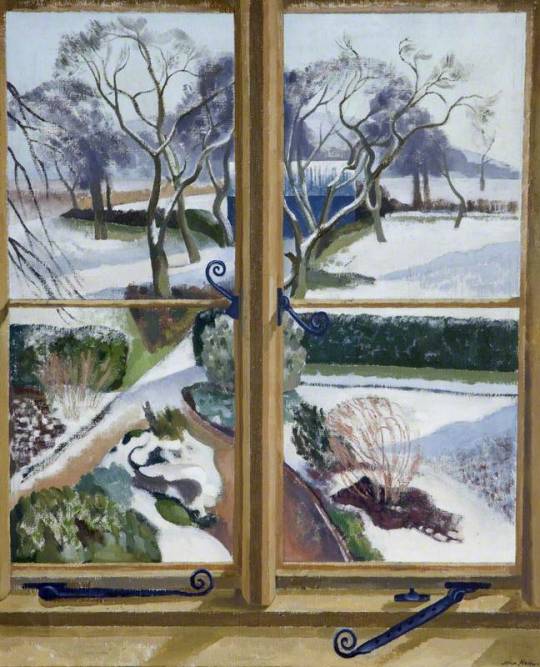

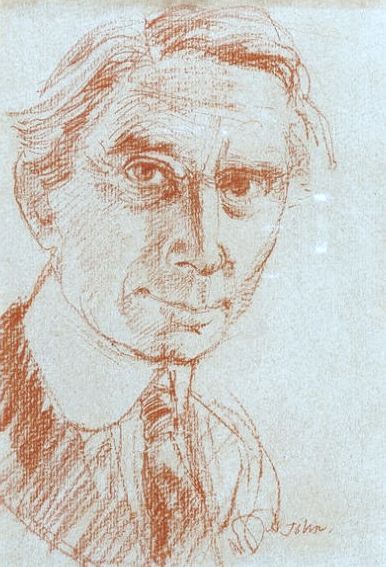

Augustus John – Self Portrait, 1920.

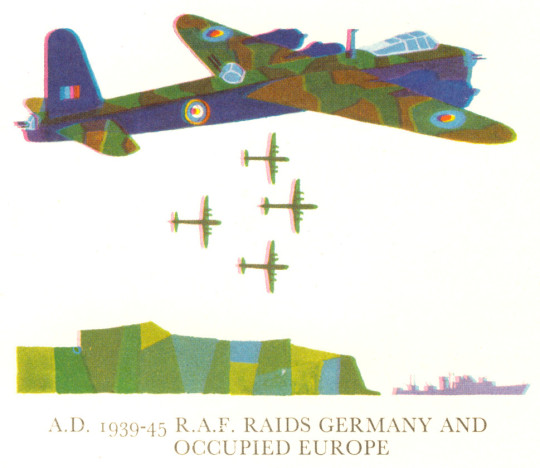

After the Second World War had effectively ended with the United States dropping the two nuclear weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th, 1945, the world was closing one door to war and opening another into the Cold War. This was both an arms-race and a stand-off. Peace movements and rallies had some worth to them then.

Augustus John joined the Peace Pledge Union as a pacifist in the 1950s, and on the 17th September 1961, just over a month before his death, he joined the Committee of 100’s anti-nuclear weapons demonstration in Trafalgar Square, London. At the time, his son, Admiral Sir Caspar John was First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff. It can only be guessed that Caspar John was not happy about it. Further more he was invited to join an CND demonstration by Bertrand Russell.

From Augustus John

Fryern Court,

Fordingbridge, Hants.

(Postmarked 15 Feb 1961)Dear Lord Russell,

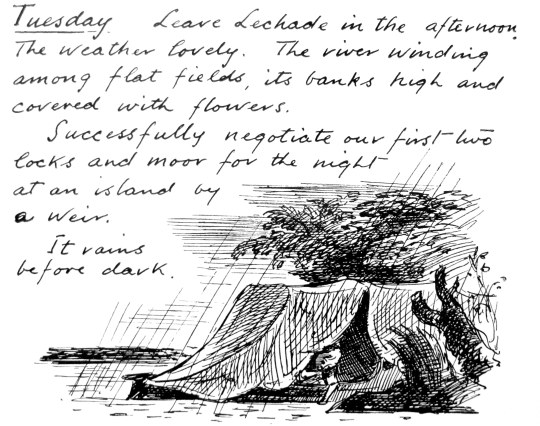

Your message was brought to me while I was working in the studio (not the one you knew, but one further off) by the gardener. I told him how to reply, which he said he understood but I don’t know if he did so correctly. All I wanted to say was that I believed in the object of the demonstration and would like to go to prison if necessary. I didn’t want to parade my physical disabilities though I still have to follow the instructions of my doctor, who I think saved my life when I was in danger of coronary thrombosis. A very distinguished medical authority who was consulted, took a very pessimistic view of my case, but my local doctor, undeterred, continued his treatment and I feel sure, saved my life. All this I meant privately & am sure you understood, even if the gardener garbled it when telephoning.I wish the greatest success for the demonstration on the 18th although I can only be with you in spirit.Your Augustus John,

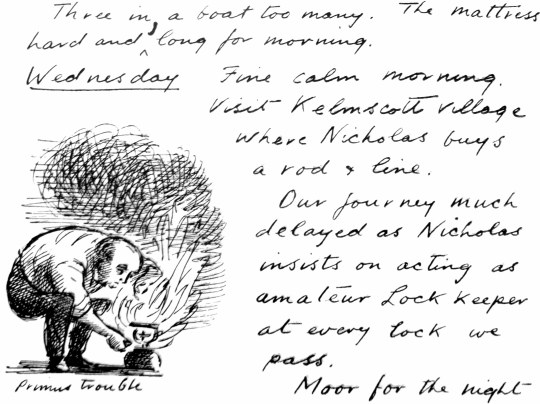

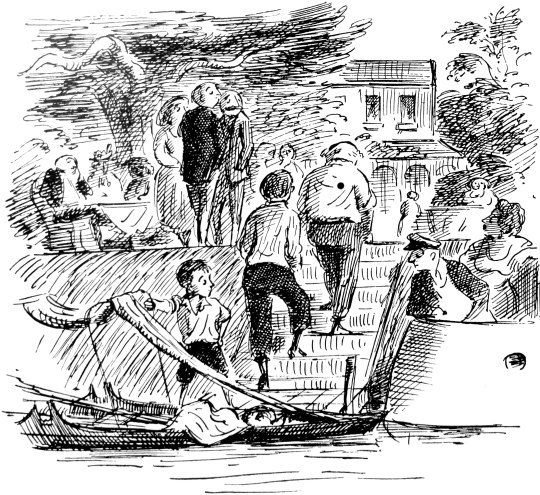

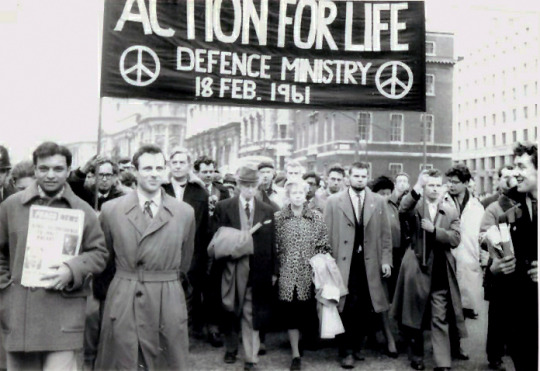

A few days later on the 18th February 1961, Bertrand Russell can be seen sitting under the banner of Action for life, a peace protest against nuclear weapons.

At a peace protest for the commemoration of Hiroshima Day on the 6th August, 1961 Russell was arrested when he took part in a sit down protest.

At the age of 89, Russell was jailed for seven days in Brixton Prison for “breach of peace” after taking part in the anti-nuclear demonstration in London. The magistrate offered to exempt him from jail if he pledged himself to “good behaviour”, to which Russell replied: “No, I won’t.”

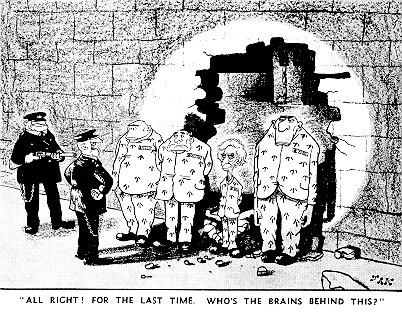

Cartoon from the Evening Standard refers to the week-long prison sentence served by Russell in September 1961.

After he had spent a week in jail he was released. In October he gave a speech in Trafalgar Square.

Extract of Russell’s Speech in Trafalgar Square, October 29, 1961

Friends,

During the last decades there have been many people who have been loud in condemnation of the Germans for having permitted the growth of Nazi evil and atrocities in their country. ‘How’, these people ask, ‘could these Germans allow themselves to remain unaware of the evil? Why did they not risk their comfort, their livelihood, even their lives to combat it?’Now a more all-embracing danger threatens us all-the danger of nuclear war. I am very proud that there is in this country a rapidly growing company of people who refuse to remain unaware of the danger, or ignorant of the facts concerning the policies that enable, and force, us to live in such danger. I am even prouder to be associated with those many among them who, at whatever risk of discomfort and often of very real hardship, are willing to take drastic action to uphold their belief. They had laid themselves open to the charges of being silly, being exhibitionist, being law-breakers, being traitors. They have suffered ostracism and imprisonment, sometimes repeatedly, in order to call attention the facts that they have made the effort to learn.It is a great happiness to me to welcome so many of them here – I wish that I could say all of them, but some are still in prison. We none of us, however can be entirely happy until our immediate aim has been achieved and the threat of nuclear war has become a thing of the past. Then such actions as we have taken and shall take will no longer be necessary.

We all wish that there shall be no nuclear war, but I do not think that the country realizes, or even that many of us here present realize, the very considerable likelihood of a nuclear war within the next few months. We are all aware of Khrushchev’s resumption of tests and of his threat to explode a 50 megaton bomb.

We all deplore these provocative acts. But I think we are less aware of the rapidly growing feeling in America in favour of a nuclear war in the very near future. In America, the actions of Congress are very largely determined by lobbies representing this or that interest. The armament lobby, which represents both the economic interests of armament firms and the warlike ardour of generals and admirals, is exceedingly powerful, and it is very doubtful whether the President will be able to stand out against the pressure which it is exerting. Its aims are set forth in a quite recent policy statement by the Air Force Association, which is the most terrifying document that I have ever read. It begins by stating that preservation of the status quo is not adequate as a national goal. I quote: ‘Freedom must bury Communism or be buried by Communism. Complete eradication of the Soviet system must be our national goal, our obligation to all free people, our promise of hope to all who are not free.’ It is a curious hope that is being promised, since it an only be realised in heaven, for the only ‘promise’ that the West can hope to fulfil is the promise to turn Eastern populations into Corpses.

The noble patriots who make this pronouncement omit to mention that Western populations also will be exterminated. ‘We are determined’, they say, ‘to back our words with action even at the risk of war. We seek not merely to preserve our freedoms, but to extend them.’ The word ‘freedom’, which is a favourite word of Western warmongers, has to be understood in a somewhat peculiar sense. It mains freedom for warmongers and prison for those who oppose them. A freedom scarcely distinguishable from this exists in Soviet Russia. The document that I am discussing says that we should employ bombs against Soviet aggression, even if the aggression is nonnuclear and even if it consists only of infiltration. We must have, it says, ‘ability to fight, win, and purposefully survive a general nuclear war’. This aim is, of course, impossible to realise, but, by using their peculiar brand of ‘freedom’ to cause belief in lies, they hope to persuade a deliberately uninformed public opinion to join in their race towards death. They are careful to promise us that H-bombs will not be the worst things they have to offer. ‘Nuclear weapons’, they say, ‘are not the end of military development. There is no reason to believe that nuclear weapons, no matter how much they may increase in number and ferocity, mark the end of the line in military systems’ development.’ They explain their meaning by saying, ‘ factor in the international power equation’. They lead up to a noble peroration: “Soviet aims are both evil and implacable.

The people (i.e. the American people) are willing to work toward, and fight for if necessary, the elimination of Communism from the world scene. Let the issue be joined.’ This ferocious document, which amounts to a sentence of death on the human race, does not consist of the idle vapourings of acknowledged cranks. On the contrary, it represents the enormous economic power of the armament industry, which is re-enforced in the public mind by the cleverly instilled fear that disarmament would bring a new depression. This fear has been instilled in spite of the fact that Americans have been assured in the Wall Street journal that a new depression would not be brought about, that the conversion from armaments to manufactures for peace could be made with little dislocation. Reputable economists in other countries support this Wall Street view. But the armament firms exploit patriotism and anti-communism as means of transferring the taxpayers’ money into their own pockets. Ruthlessly, and probably consciously, they are leading the world towards disaster. Two days ago The Times published an article by its correspondent in Washington which began: ‘The United States has decided that any attempt by East Germany to close the Friedrichstrasse crossing between West and East Berlin will be met by force.’ These facts about both America and Russia strengthen my belief that the aims that I have been advocating for some years, and upon which some of us are agreed, are right. I believe that Britain should become neutral, leaving NATO to which, in any case, she adds only negligible strength. I believe this partly because I believe that Britain would be safer as a neutral, and without a bomb of her own or the illusory ‘protection’ of the American bomb, and without bases for foreign troops; and, perhaps more important, I believe it because, if Britain were neutral, she could do more to help to achieve peace in the world than she can do now. †

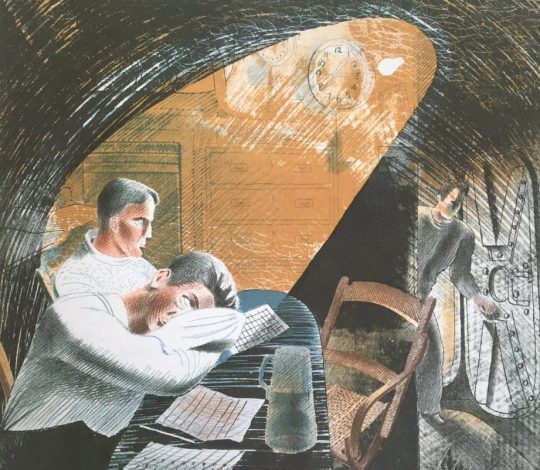

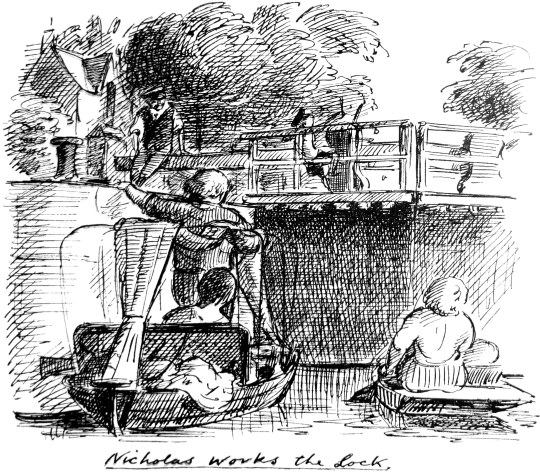

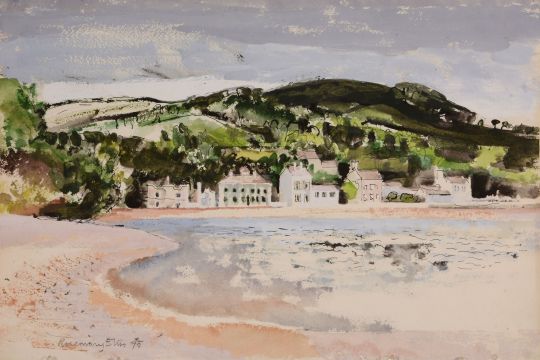

Augustus John’s portrait of Bertrand Russell.

† Bertrand Russell’s America: His Transatlantic Travels and Writings. Volume Two 1945-1970: 2