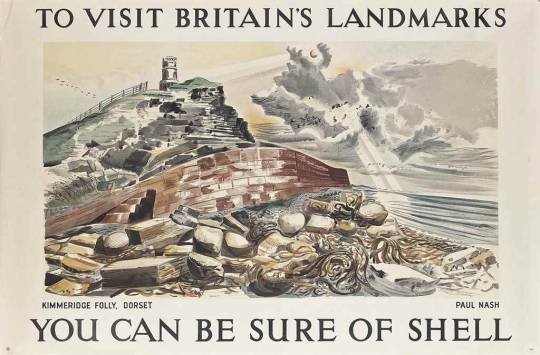

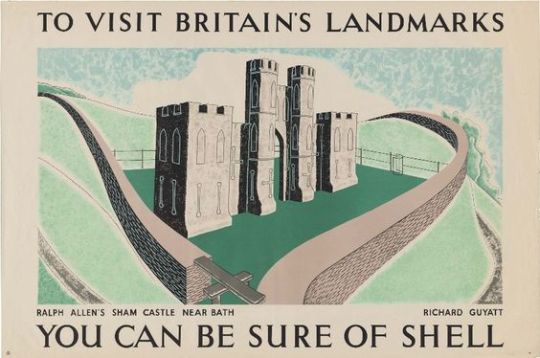

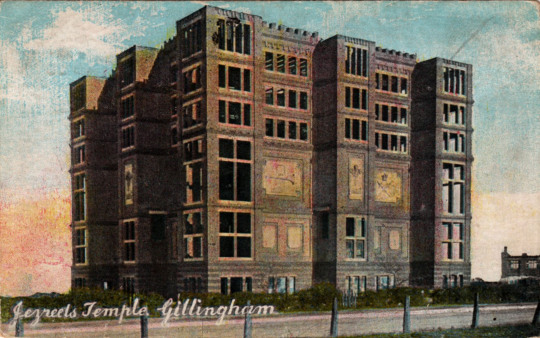

One of the most famous follies in Britain was in Gillingham. It was a folly for it was never completed, it was to be the Jezreel Temple of the Flying Roll. It was built by a religious sect, led by an ex-Indian army corporal

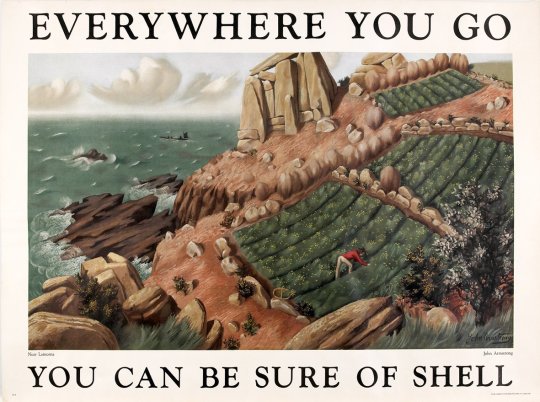

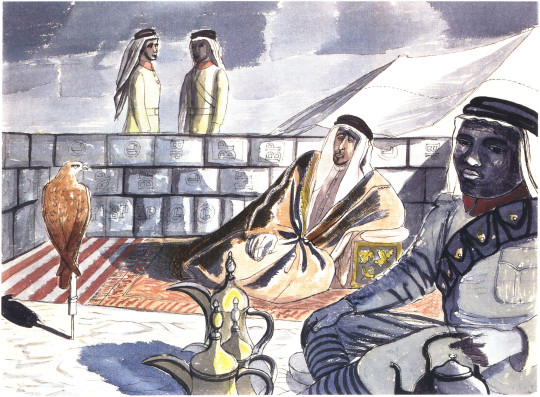

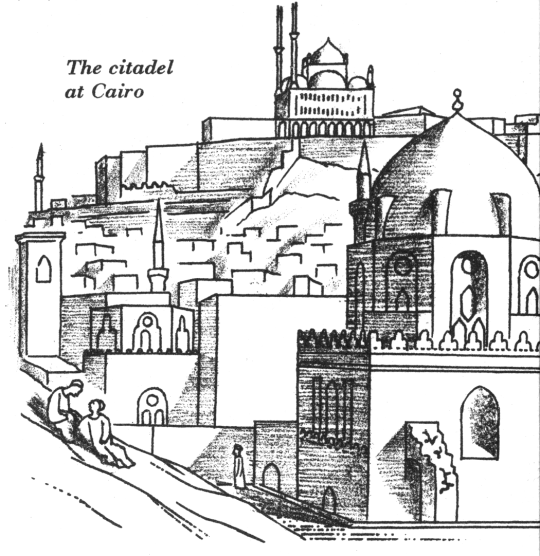

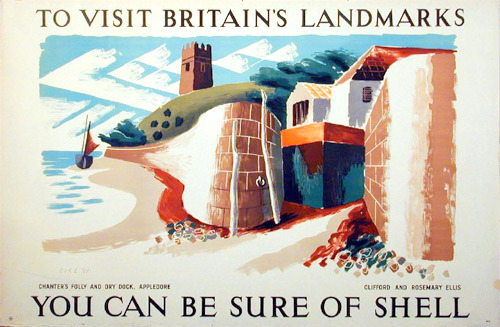

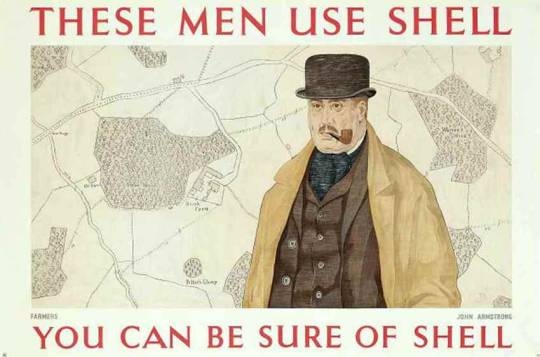

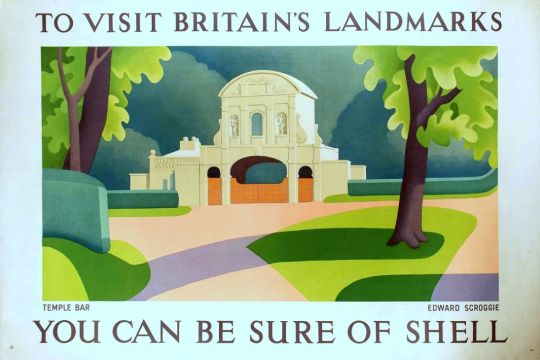

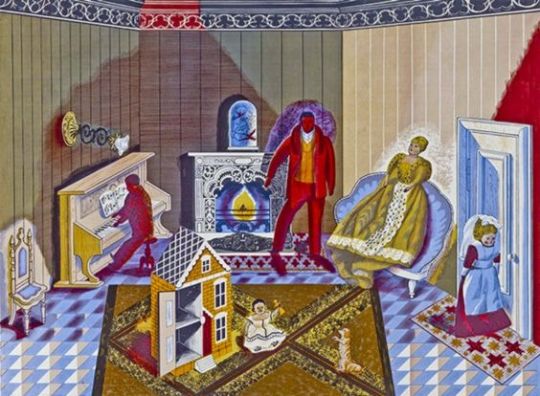

James Roland White, later known as James Jershom Jezreel. It was painted by Tristram Hillier for one of the Shell Posters.

Tristram Hillier – Jezreel’s Temple Shell Poster, 1936

The printed word in books, pamphlets, newspapers and the postal service may have helped the social situation that made for a boom in new religious orders at the time. In America there were the Mormans but in Britain there was also a wide range of strange religions and cults based on Christ, the power of the pyramids or séance and speaking with the dead, but mostly cranks seeking power. It happens that I collect the books of such people (especially on the pyramids), as a comedic and weird area of my library.

James White enlisted in the British Army on 27 July 1875 joining the 16th Regiment of Foot as a private, based in Chatham, Kent. It was at this time that White was also becoming interested in other spiritualists who had become famous. One was Joanna Southcott, a domestic servant who aged 42 in 1792 believed she had supernatural powers. Southcott wrote and

dictated prophecies in rhyme, announced herself as the Woman of the

Apocalypse spoken of in the Book of Revelations.

John Wroe was another inspiration. Wroe had set up the Christian Israelite Church at Chatham in 1875. The church was originally set up in Gravesend, Kent, ten miles from Gillingham.

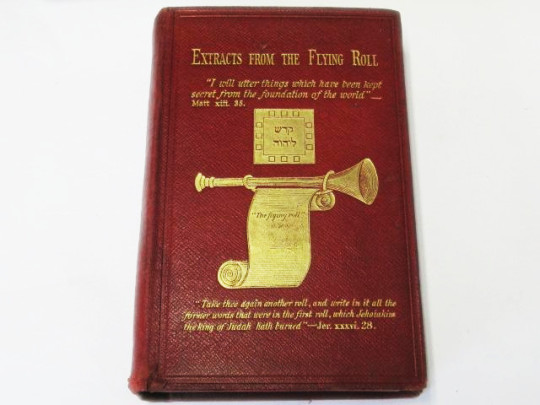

White, while in Secunderabad, India, with his regiment complied a book made up from the writings of Johanna Southcott and John Wroe. To this compilation he gave the title of “The Flying Roll.” It is emblematically sculptured on the western tablet on the south front of the tower building as it remains today. The Flying Roll was described as a “ramshackle” book, made up of extracts “ransacked from the Bible, from Genesis to Revelations” together with references to Southcott and Wroe.

White joined a small branch of a Southcottian sect of Christian Israelites at Chatham, led by a Mr and Mrs Head and calling itself the New House of Israel. Shortly after joining he wrote a version of the manuscript to become known as the “Flying Roll” and took over the church. White adopted the name of James Jershom Jezreel and persuaded some worshippers that he was the Messenger of the Lord. White also went to Wrenthorpe, in Yorkshire, taking his “Flying Roll” with him. Here dwelt a community that had long followed John Wroe and Johanna Southcott. To these he made a fervid appeal claiming himself to be “a messenger sent by God to succeed their former prophet.” They promptly rejected both him and “Flying Roll.” He then returned to Chatham. As the “Flying Roll” had so signally failed him in both of these early appeals James decided to keep it back for later and happier days.

White completed his military service in 1881 and left the army to set about building a headquarters for his church. Leaving the army he changed his name from White and went on to be called Jezreel.

The site for his church was at the top of Chatham Hill and the highest point in the area. It was chosen, Jezreel said, after a revelation from God.

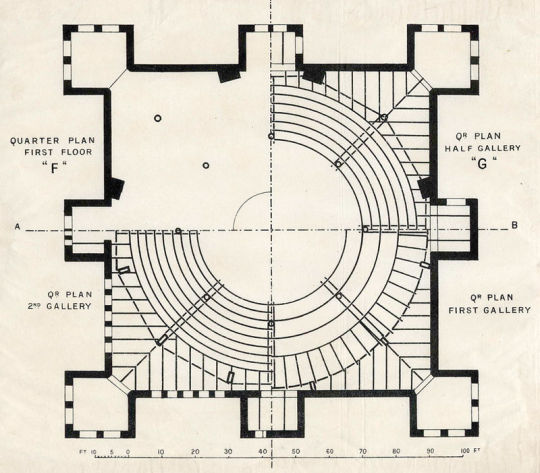

He envisaged a building based on Revelation xxi, 16: “And the city lieth foursquare, and the length thereof is as great as the breadth … the length and the breadth and the height thereof are equal.” It was intended to be a

sanctuary, assembly hall and headquarters of the New and Latter House

of Israel, as the church was now called.

Around the perimeter there would be shops plus accommodation for Israel’s International College, a school he had already set up at his home in Woodlands Road, Gillingham.

Jezreel wanted the new HQ to be a perfect cube, each side 144 ft long. The architects, however, persuaded him the design was impractical and he agreed a modified version – 124 ft on each side and 120 ft high at each corner. It was to be built of steel and concrete with yellow brick walls and eight castellated towers. The trumpet and flying roll, crossed swords of the spirit and the Prince of Wales feathers (signifying the Trinity), were to be engraved on the outer walls.

First, an enormous cellar had to be constructed for storage, lift machinery, a heating system and the all-important printing presses to turn out thousands of copies of the Flying Roll and other literature essential to the

sect.

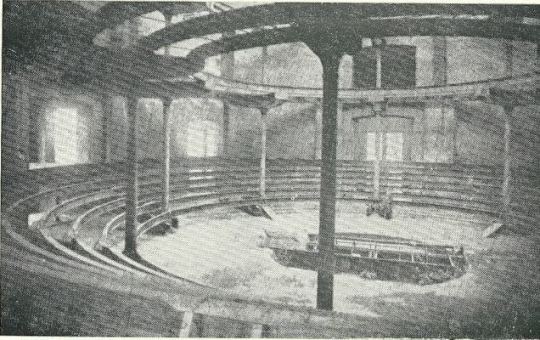

The circular assembly room was a vast amphitheatre, said to be capable of accommodating up to 5,000 people. In the roof would be a glass dome, 94 ft in diameter. Jezreel planned gardens and stately avenues from adjoining streets, making it a focal point for the area. The estimate for these plans was £25,000 and completion was set for 1 January 1885. The money came from his followers savings and fundraising.

Jezreel insisted his followers were abstainers from drink – a rule that did not apply to the leader, who often appeared to be drunk.

Jezreel fell ill towards the end of 1884 and died on 2 March 1885. Nobody mourned his death, for the word was without meaning in the sect, who expected his speedy resurrection. His coffin bore the simple inscription James Jershom Jezreel, aged 45 years, and was buried in an unmarked grave in the Grange Road cemetery near his home in Gillingham.

The sect was taken over by his wife Clarissa (née Rogers), a follower 10 years his junior whom he had married on 17 December 1881. (On the marriage certificate she added the name Esther by which she was then known.) She ensured the building work continued. The foundation stone was laid on 19 September 1885.

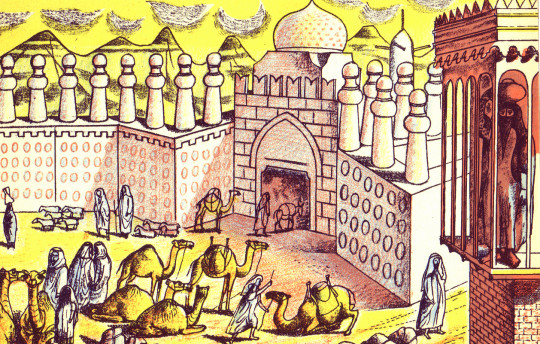

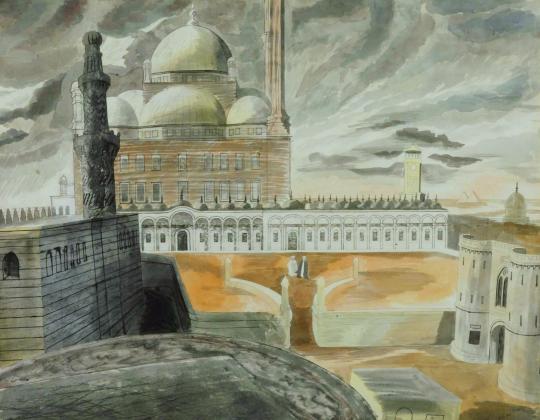

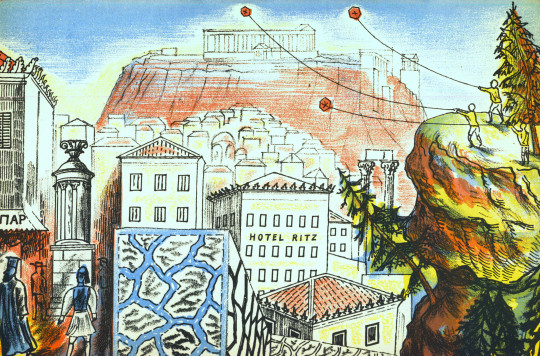

Digital version of White’s original design.

Much of the tower’s foundations were in place by early 1886 and some of the peripheral buildings were occupied. As building costs soared, Clarissa made economies in the budget for keeping followers. She found the cost of feeding Jezreelites was particularly high and declared the sect would become vegetarian, living off a diet of bread and potatoes.

“Queen Esther” (the derogatory name by which she was called in the press), however, was often to be seen in the area riding in a coach and dressed in fashionable clothing. Inevitably, this led to dissent and the number of followers – at one point as high as 1,400 – began to dwindle. After a legal case involving one of the followers, who had given all his money to the cause, a mere 160 Jezreelites remained.

By June 1887, the whole of the outside except for the roof was finished, while inside the ground floor was complete with the newly installed steam printing-presses rapidly turning out the sect’s publications – the ‘Flying Roll’ and ‘Messenger of Wisdom’. On the floor above, large quantities of steel girders had been installed to construct the meeting hall, balconies, the hydraulic choirs and preacher’s revolving platform.

However, payments to the builders began to slow down. In November 1887, the building was ready for its concrete and asphalt roof but this had to be delayed, and as the money finally ran out in March 1888, work ceased. So, roofless and surrounded by scaffolding, Jezreel’s fantastic tower lay exposed to the elements. By that time, £30,000 had been spent and it was estimated that another £20,000 would be needed. There was a possibility that the building could have been finished, but the sudden death of Esther in June 1888 removed the Jezreelites’ unifying influence and almost certainly ensured that this would not happen.

In July, 1888, Mrs Jezreel died suddenly from peritonitis. She was 28. The sect fragmented and work on the tower was suspended forever. It was demolished in 1961. The shops (and members accommodation) mentioned near the site of the tower and demolished in 2008.