In July 1933 the Nash went on holiday to Marlborough with his friend Ruth Clark. From there they made a day trip to nearby Avebury. This is a video of his photographs, drawings and paintings he made inspired by the Stones.

In July 1933 the Nash went on holiday to Marlborough with his friend Ruth Clark. From there they made a day trip to nearby Avebury. This is a video of his photographs, drawings and paintings he made inspired by the Stones.

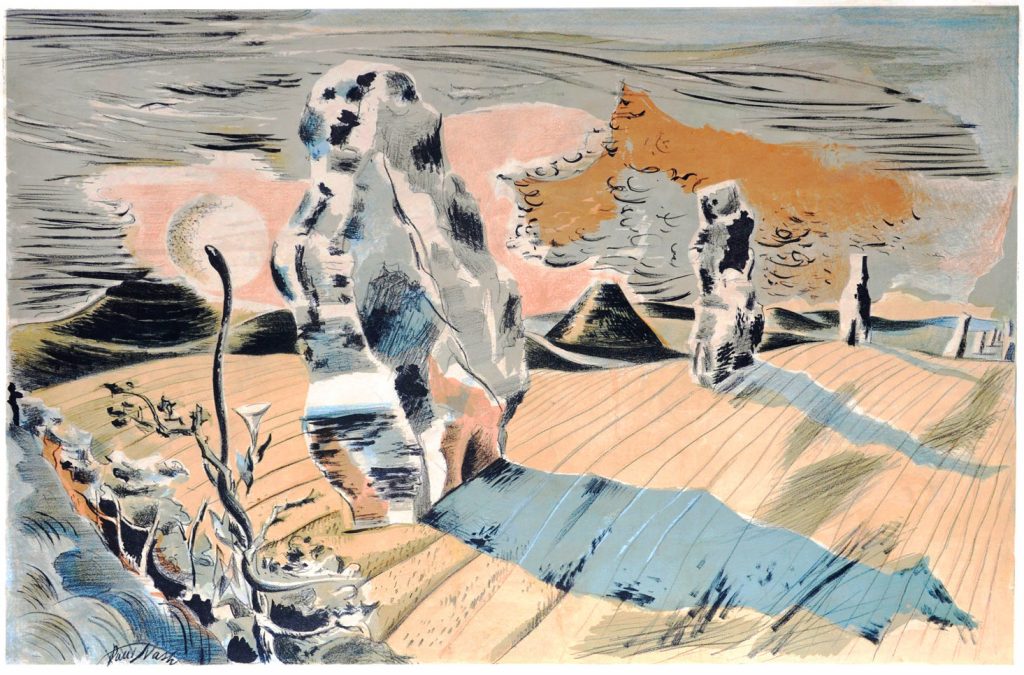

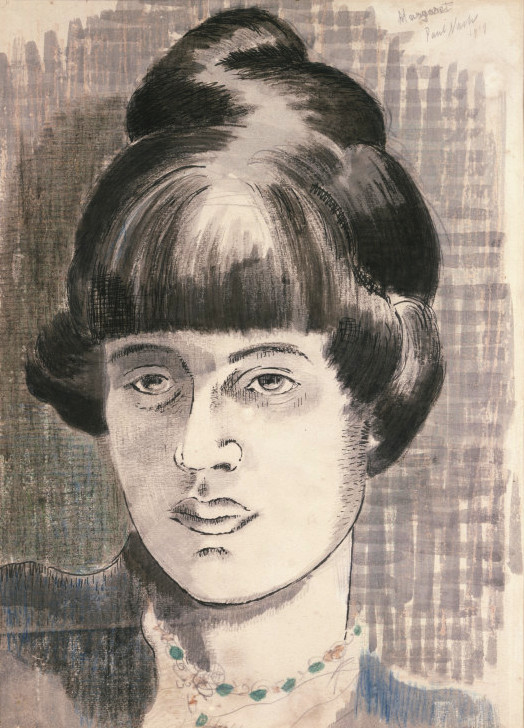

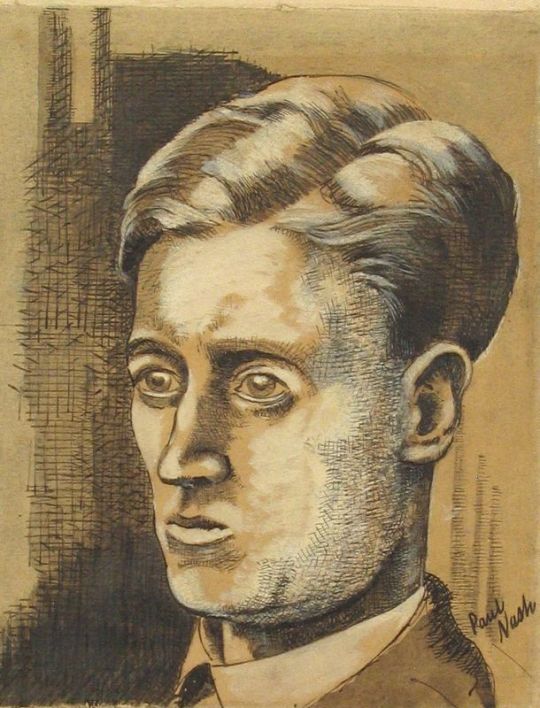

Many people might be unaware that Paul Nash did portraits, few are finished works but some are in illustrated letters. To me they are rather pleasing and the dress and hair of the sitters is also of the era. I picture them being drawn in a 1930s sitting room by a fire.

Paul Nash – Margaret Nash, 1919

Margaret Theodosia Odeh was born in Jerusalem, Nash grew up in Cairo. She was the daughter of an Anglican minister. Shortly after moving to London in 1908, she became involved in the suffrage movement and the Tax Resistance League. One of the founding members of the Committee for Social Investigation and Reform, Nash offered rehabilitation and opportunities for women working as prostitutes. With funding from donors including Millicent Fawcett and Elizabeth Anderson, the Women’s Training Colony in Berkshire was established. Women could stay at the retreat and learn arts and crafts, including millinery. The initiative was inspired by the Arts and Crafts objective to improve people’s lives through craft. She also worked on textiles at the Omega Workshops run by the Bloomsbury group. She married Paul Nash in 1913.

Paul Nash – Portrait of Alice Daglish, 1921

Alice (nee) Archer is known mostly for The Land of Nursery Rhyme, 1932, a book she co-edited with Ernest Rhys. It was illustrated by Charles Folkard. She married Eric Fitch Daglish in 1918 and lived to be 103.

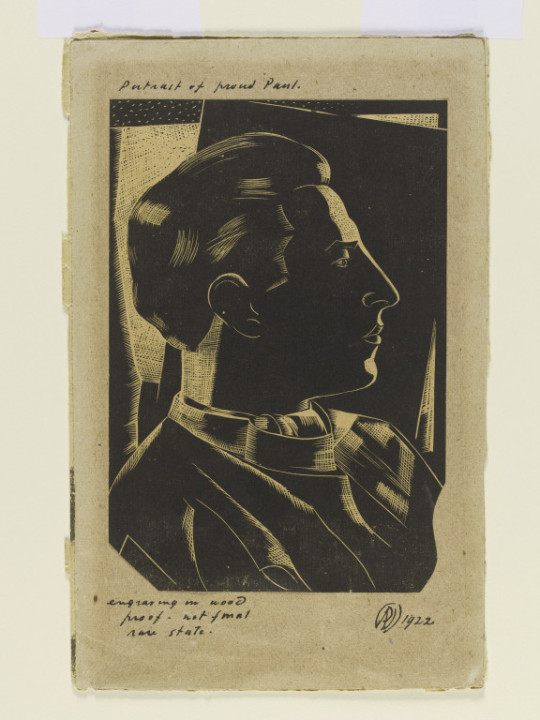

Paul Nash – Yvonne, 1922 (Maybe Yvonne Gregory)

Paul Nash – Douglas Goldring

Douglas Goldring was an English writer and journalist. He became known mostly as a travel writer. In the late 1930s Goldring came to prominence in two ways. He was Secretary of the Georgian Society, which he helped to found after writing in the Daily Telegraph in 1936, with Lord Derwent and Robert Byron. Inspired by the ideas of William Morris, Goldring helped transform it in 1937 into the Georgian Group, a section within the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, on the advice of Lord Esher.

Goldring soon became unhappy with the Georgian Group’s political conservatism and left it. He was also noted, at the same period, as a radical journalist and prolific contributor to left-wing publications. Goldring described his political views as socialist. In his last years, Goldring contributed reviews to the Socialist Labour League magazine Labour Review.

Paul Nash, Barbara, c1910

Paul Nash – Self Portrait, 1922

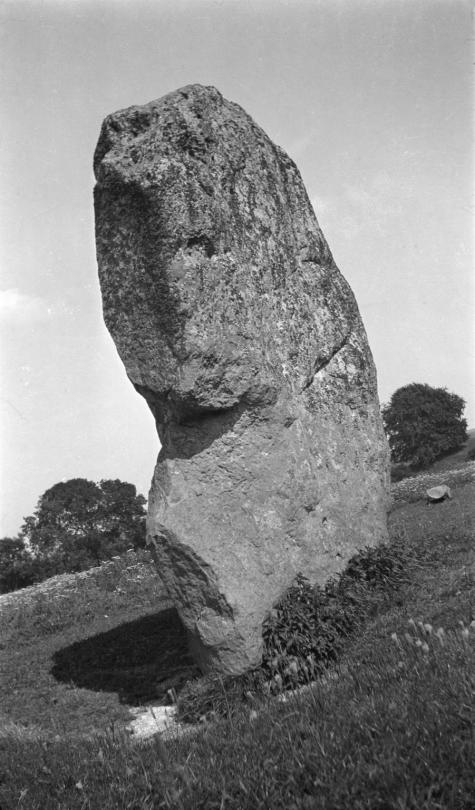

Avebury is a Neolithic henge monument containing three stone circles. The Village of Avebury in Wiltshire was built around them and now bisect the circle with a High Street. Avebury contains the largest megalithic stone circle in the world. Constructed over several hundred years in the Third Millennium BC, during the Neolithic, or New Stone Age, the monument comprises a large henge (a bank and a ditch) with a large outer stone circle and two separate smaller stone circles situated inside the centre of the monument.

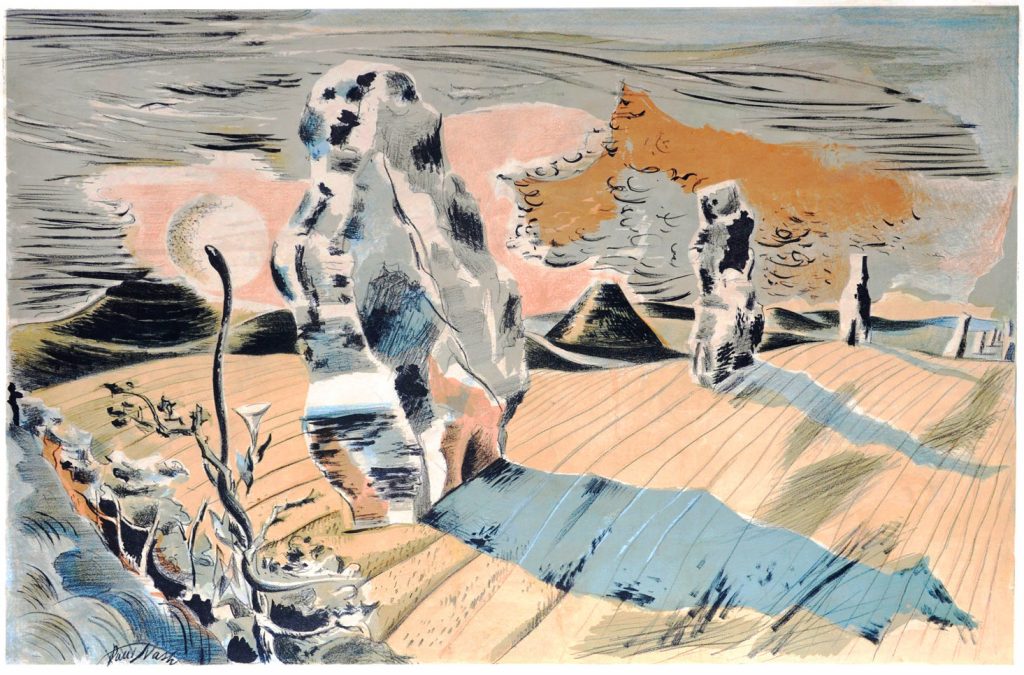

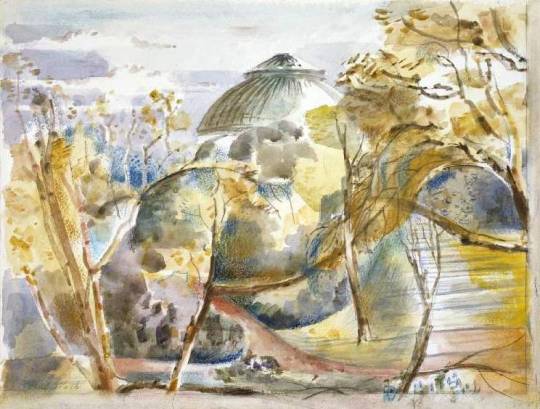

Paul Nash – Avebury, 1936

When England was converted to Christianity, Avebury was considered a non-Christian monument. At some point in the early 14th century, villagers began to demolish the monument by pulling down the large standing stones and burying them in ready-dug pits at the side. During the toppling of the stones, one of them (which was 3 metres tall and weighed 13 tons), collapsed on top of one of the men pulling it down, fracturing his pelvis and breaking his neck, crushing him to death. Trapped in the hole that had been dug for the falling stone he was found by archaeologists in 1938. They found that he had been carrying a leather pouch, in which was found three silver coins dated to around 1320–25, as well as a pair of iron scissors and a lancet.

In the latter part of the 17th and then the 18th centuries, destruction at Avebury reached its peak. The majority of the standing stones that had been a part of the monument for thousands of years were smashed up to be used as building material for the local area. This was achieved in a method that involved lighting a fire to heat the sarsen, then pouring cold water on it to create weaknesses in the rock, and finally smashing at these weak points with a sledgehammer.

In the 1920s Marconi wanted to build a radio station on the hills above Avebury and the Air Ministry wanted to close Wayland Smithy area with standing stones as a bombing range in the 1930s . †

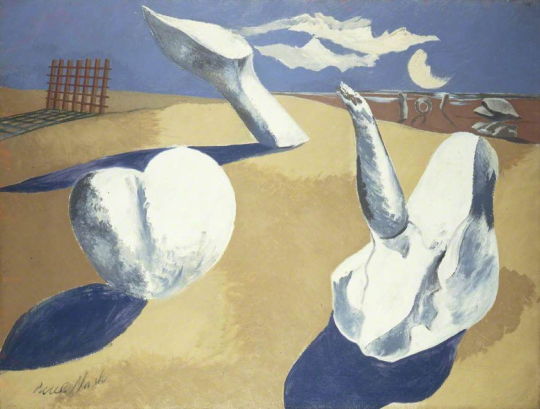

Paul Nash – Avebury, Personage, 1933

In July 1933 the ailing Nash went on holiday to Marlborough with his friend Ruth Clark. From there they made a day trip to nearby Avebury. ‡

Paul Nash – Avebury Stone (Double Exposure), 1933

The epiphany that Paul Nash had to use he standing stones artistically, seems to have come with an interest in the Neolithic period in publishing with the British Public. It is an era where Paganism has become popular, as many alternative religions did after the First World War. In trying to make sense of the carnage and brutality of the War the public looked for ancient wisdom and this maybe why we have to tolerate people smothering themselves over Stonehenge every solstice.

In these paintings and photographs Nash was also documenting an interest that other artists such as Henry Moore had in the primitive. Moore looked towards early Peruvian pottery and flints for organic shapes and old works made by early man. These monuments are the few examples of art that survive. Even in the medieval period the only arts to survive in Britain of the common man would be the carvings of bench-ends in churches, pottery or other folk art.

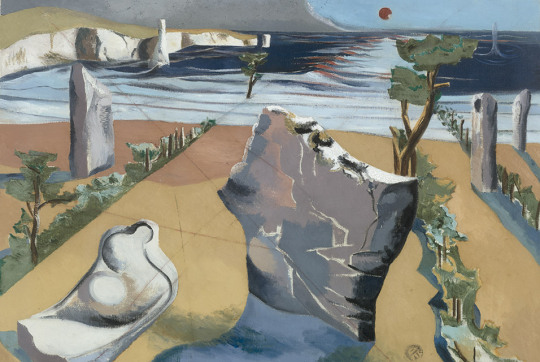

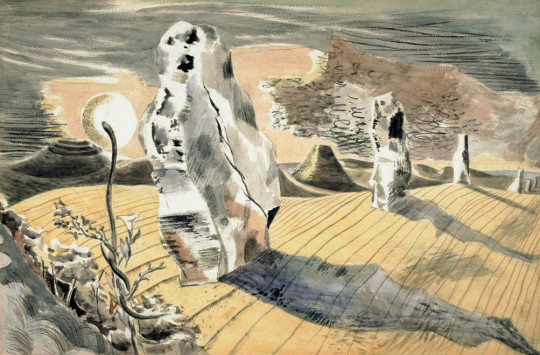

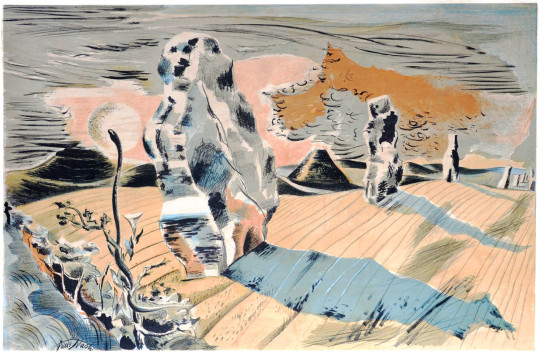

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Megaliths, 1934

Margaret Nash said this was Paul’s first painting of the Avebury stones, which he saw in August 1933. Nash himself gave the following description of Avebury in ‘Picture History’ The preoccupation of the stones has always been a separate pursuit and interest aside from that of object personages. My interest began with the discovery of Avebury megaliths when I was staying at Marlborough in the Summer of 1933. The great stones were then in their wild state, so to speak. Some were half covered by the grass, others stood up in the cornfields were entangled and overgrown in the copses, some were buried under the turf. But they were always wonderful and disquieting, and, as I saw them then, I shall always remember them … Their colouring and pattern, their patina of golden lichen, all enhanced their strange forms and mystical significance. Thereafter, I hunted stones, by the seashore, on the downs, in the furrows. ♣

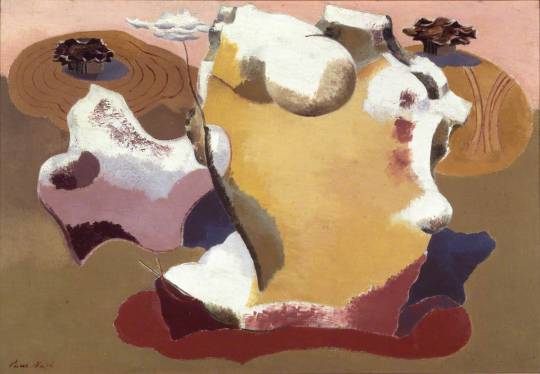

Paul Nash – The Nest of Wild Stones, 1937

I found my first nest of wild stones on looking closely into a drawing I had made of some bleached objects on the Swanage Downs. It lay just below the level of my consciousness, slightly out of focus. But there was no mistaking its lineaments a moment later when I moved the dry thoughts to one side. ♠

Below Paul Nash writes of the effect of Avebury on his work. That he wasn’t only painting the stones themselves but placing ordinary stones he found in a picture as if they were large monuments.

In most instances, the pictures coming out of this preoccupation were concerned with stones seen solely as objects in relation to the landscape. But later certain stone personages evolved, such as the stone birds in the ‘Nest of Wild Stones’ and the more ‘abstract’ forms in ‘Encounter in the Afternoon’. ♣

Many of these works may be down to another external influence, Eileen Agar. Nash had met and fallen in love with Agar, who was a surrealist artist and using stones and found objects in her works around the same time.

Paul Nash – Photograph of Stones in his Studio, 1936

Paul Nash – Encounter in the Afternoon, 1936

Paul Nash – Landscape of Bleached Objects, 1934

Paul Nash – Circle Of The Monoliths, 1937-8

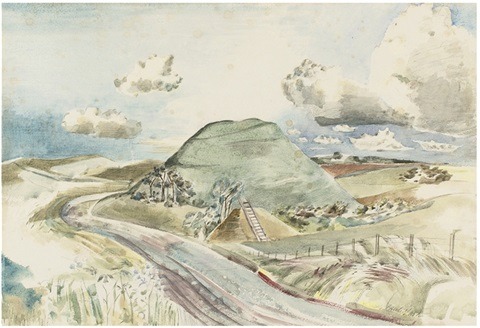

In the painting above (Circle of the Monoliths) is the stepped hill what is likely Silbury Hill. The construction of the hill in the Late Neolithic period was originally stepped, then filled in. Silbury Hill is very close to Avebury.

When the artist Paul Nash first visited Avebury in 1933 he was amazed by the scale of Silbury Hill and by the ancient circle of megaliths, the great glacial boulders that had been dragged from the Downs in prehistoric times. ♥

Paul Nash – Silbury Hill, 1938

Paul Nash – Silbury Hill, c1937

All Nash’s other statements about Avebury and stones are much more direct, it is almost as if he contrived to intellectualise his ideas simply to be provocative, but in face the Landscape of the Megaliths Nash does resolve the equation. The picture shows the adventure of stones receding away from the spectator, in the foreground in the convolvulus curls round a snake which rises upwards. ♦

Paul Nash – Avebury Stone, 1933

The stones at Avebury come up again when Nash was asked to illustrate a cover to the magazine Countrygoing. Though I think it was commissioned in 1938 it was published in 1945.

A Paul Nash Cover to Countrygoing, 1945

Paul Nash – Circle Of The Monoliths, 1937-8

Above is the finished painting of Circle Of The Monoliths. Below is the study for the work that was found painted on the back of The Two Serpents c 1937.

Paul Nash – Circle of the Monoliths, 1937-1938

Nash’s abstraction of stones in the 1930s went on with his distortions of landscapes, found stones and the real Neolithic stones. In we see Mên-an-Tol and the stone ring there placed in the top right corner in front of more found stones. To the right is a grid that can only be echoing Encounter in the Afternoon and Circle Of The Monoliths.

Paul Nash – Nocturnal Landscape, 1938

Below we see the same Avebury stone used on the cover to Countrygoing with the wedge shaped cut in the side.

Paul Nash – Druid Landscape, 1938

Initially, using a No.1A pocket Kodak series 2 camera, Nash captured images so that he could refer to them in the creation of his paintings. Increasingly, however, he saw his photographs, not as aids or sketches, but as artworks in their own right.

Here Nash depicts one of the Avebury Sentinels, and his choice of subject matter is characteristic. Nash was always interested in landscapes and aspects of the natural world, not for their historical or aesthetic interest per se, but more because he thought that certain places as he called them (see Biography) had about them a mystical importance, a genius loci; which lent the place, the stone, the tree, an importance which transcended its apparent properties. As he wrote there are places whose relationship of parts creates a mystery, an enchantment. It is this mystery, this enchantment, which Nash tries to capture in his photographs. ◊

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1933

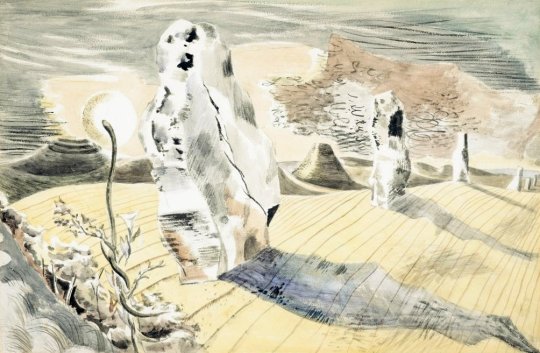

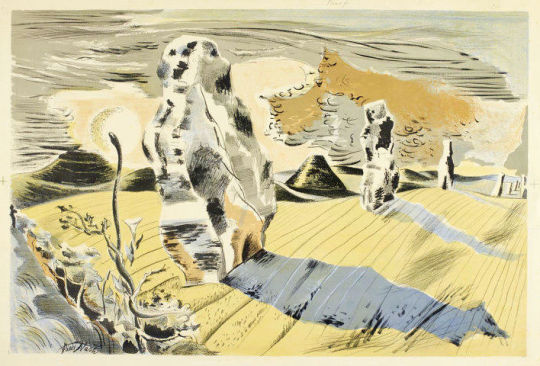

Some of the quote below may be a repeat of what has been read about Nash, but I featured it for the Convolvulus park that features in Landscape of the Megaliths. In the background of the watercolour and lithograph below are two hills, both likely to be a Neolithic Sidbury Hill and how it looks today.

Last summer I walked in a field near Avebury where two rough monoliths stand up … miraculously patterned with black and orange lichen, remnants of the avenue of stones which led to the Great Circle. In the hedge, at hand, the white trumpet of a convolvulus turns from its spiral stem, following the sun. In my art I would solve such an equation

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Megaliths – Watercolour, 1937

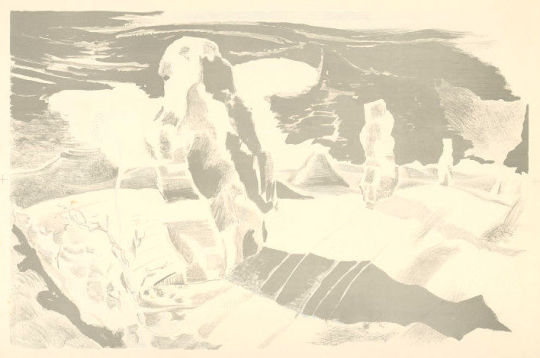

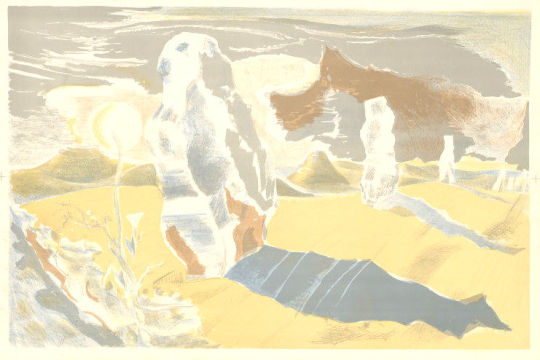

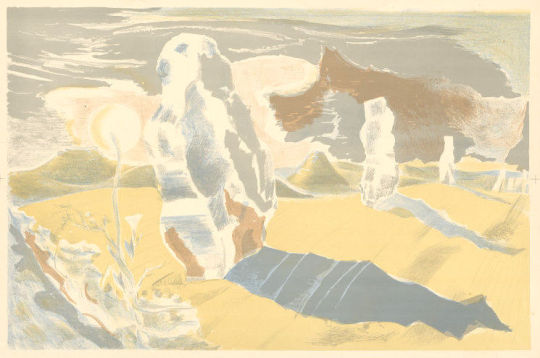

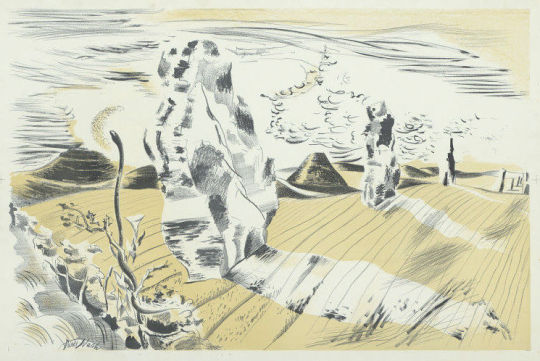

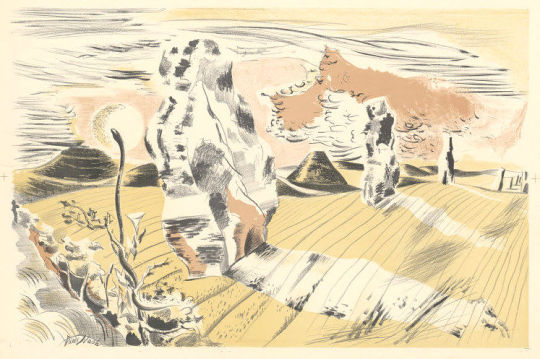

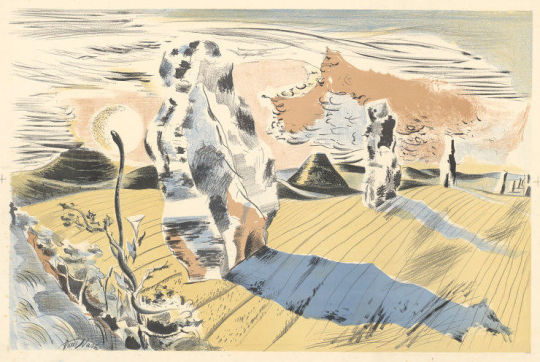

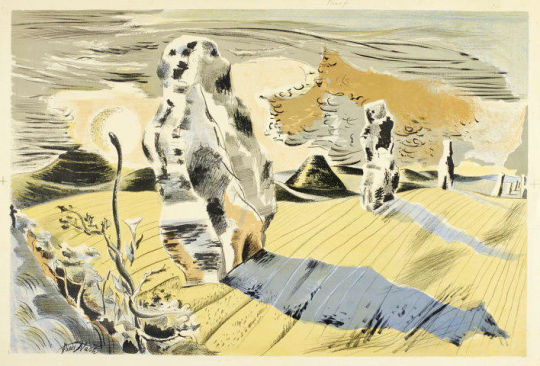

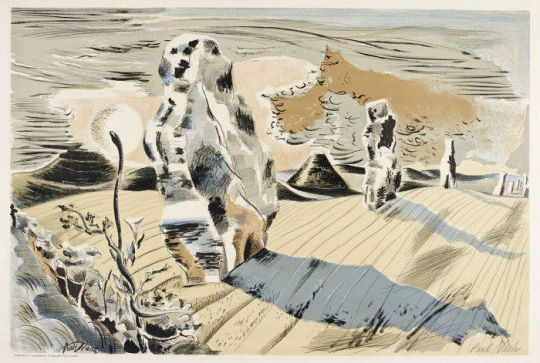

Some time ago I made a blog post on Paul Nash and the process of colour layers used to make the lithograph below.

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Megaliths – Lithograph, 1937

The photographs below are dated 1942 by the Tate. I don’t know is Nash went back to Avebury or if they are catalogued wrongly. But I thought it was worth including them with the car by the roadside.

Paul Nash – Avebury, 1942

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1942

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1942

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1944

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1944

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1944

Paul Nash – Avebury, 1944

† Joanne Parker – Written on Stone: The Cultural Reception of British Prehistoric, 2009

‡ David Boyd Haycock – Paul Nash, p54, 2002

♠ Andrew Causey – Paul Nash: Writings on Art – Page 142

♣ Paul Nash – Paintings and Watercolours Exhibition Catalogue, Tate, 1975

♥ Julius Bryant – The English Grand Tour, p16, 2005

♦ Paul Nash, Places, South Bank Centre, 1989

◊ Art Republic

Paul Nash – St Pancras, London, 1932

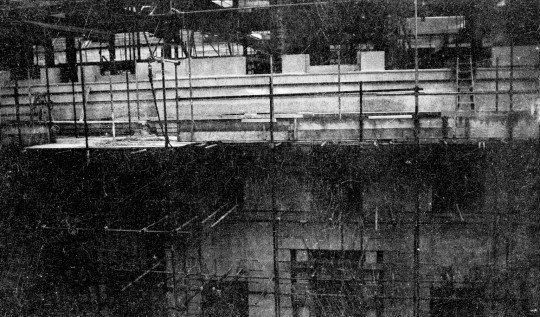

Paul Nash lived in Flat 176, Queen Alexandra Mansions between 1914 and 1936. It belonged to Margaret Odeh before then, he married her and moved in. I would guess he moved out in 1936 because his view of St Pancras Hotel was gone due to the construction of St Pancras Town Hall, later known as Camden Town Hall on Euston Road, designed by A. J. Thomas. In the photographs below you can see Margret and Paul’s view disappearing with the scaffolding and construction.

Paul Nash – St Pancras, London, 1932

Paul Nash – St Pancras, London, 1932

The Nash’s lived on the 5th floor and this is the view from their window looking out. It is level with the top of the council offices.

And below is the site as it looks today but would have also looked in 1936 when complete.

Andrew Cusack – St Pancras and Camden Town Hall, 2017

Below are the happier times for the Nash’s when they had a view and Paul was able to paint from his window various flower paintings using the same jug.

Paul Nash – St Pancras Lilies, 1927

Paul Nash – St Pancras, London, 1927

I show below the process of buildings that faced the midlands hotel. First is Titford and Co – Funeral Furniture, Coffin Makers and undertakers – 131 Judd Street.

St Pancras Railway Station, April 1899

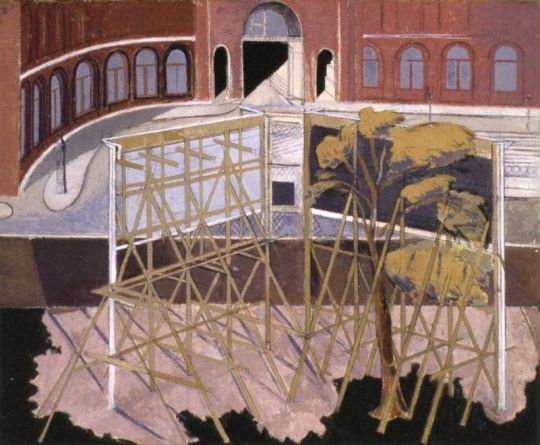

Here you see the buildings and gardens gone and the plot of land with signage that Nash would translate in his Nortern Adventure Picture.

St Pancras, London, 1925

Rather like Eric Ravilious at this time, Paul Nash became inspired by the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico. He translated the signage of construction seen above by the fence into the image below.

Paul Nash, Northern Adventure, 1929.

The painting below is more in Nash style, less abstract but it uses most of the hotel’s arched doors and windows, a favourite motif of de Chirico. The billboards have signage on them so I suppose this is the later image. The name ‘Nostalgic Landscape’ likely noting the view, now lost.

Paul Nash – Nostalgic Landscape, St. Pancras Station, 1929

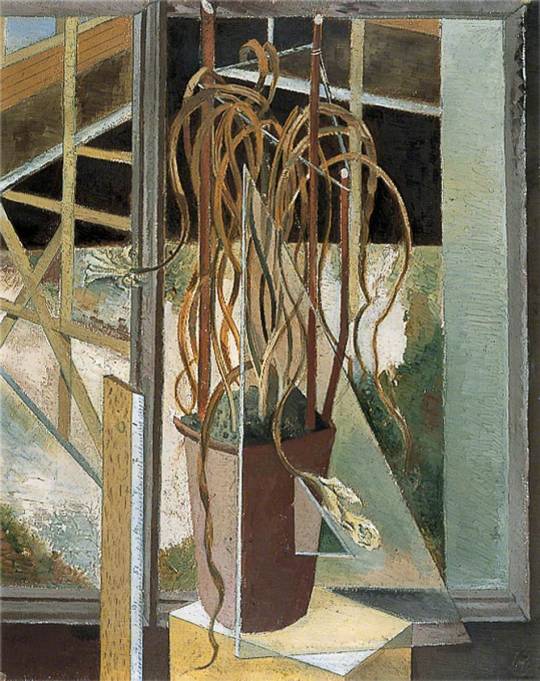

The image below Dead Spring is said to be a reaction against the artist’s father dying.

February 1929 Nash’s father died. Margaret Nash told Bertram that ‘nothing in their whole married life so profoundly affected her husband as his father’s death’ †

I don’t know I know if I buy into that idea that the painting conveys this. I think it is likely a protest putting the building site and his newly found style to good use. It is also said that the plant is dead, but the plant isn’t dead as it is in flower. I think it’s the landscape that is now dead, not the plant. The geometrical tools and rulers, the type a builder would use, and the features that make me think the outside is the dead world, while poking fun at the technique of de Chirico. They appear in the photo at the bottom of this post.

Paul Nash – Dead Spring, 1929

Paul Nash – St Pancras, London, 1932

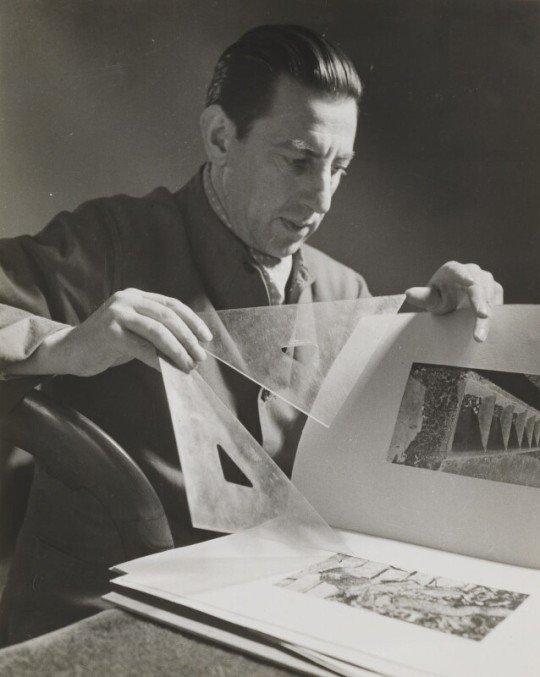

Helen Muspratt – Paul Nash, 1932

† Paul Nash, paintings and watercolours, p23, 1975

Paul Nash – Landscape of the British Museum, Fitzwilliam Museum

One of the arguments for not leaving a good bit of art to a large museum is that it might never be seen. The idea that your gift may end up in the endless archives of the Tate Gallery or Towner comes with that danger. When Edward Bawden was looking to leave his studio to someone he chose the Higgins Gallery in Bedford because they were much smaller and would be more likely to exhibit his works, though for some time that was not what happened. (It was a decision he apparently regretted when the Fry Gallery was founded in 1985 and opened in 1987.) If work sits in archive storage this might give more weight to my constant quest for Why not a Tate East?

I digress – the other day while looking up engraved windows by John Hutton I discovered the The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge have an online archive of the pieces they own, many of them being in archives not on display and it shocked me to see how many works by Paul Nash they had.

Living in Cambridge one of the things visitors to the city want to see is the Fitzwilliam’s amazing collection of art, but to me a lot of it doesn’t rotate and so I find going rather boring. I wish they could set a rotating room or explore their archives for exhibitions. Below the paintings are mostly from the collection of Paul Nash’s in the Fitzwilliam Museum archives.

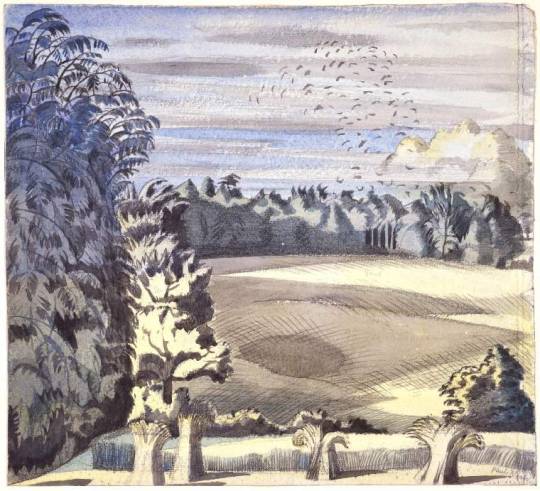

Paul Nash – Landscape with Rooks, 1913, Fitzwilliam Museum

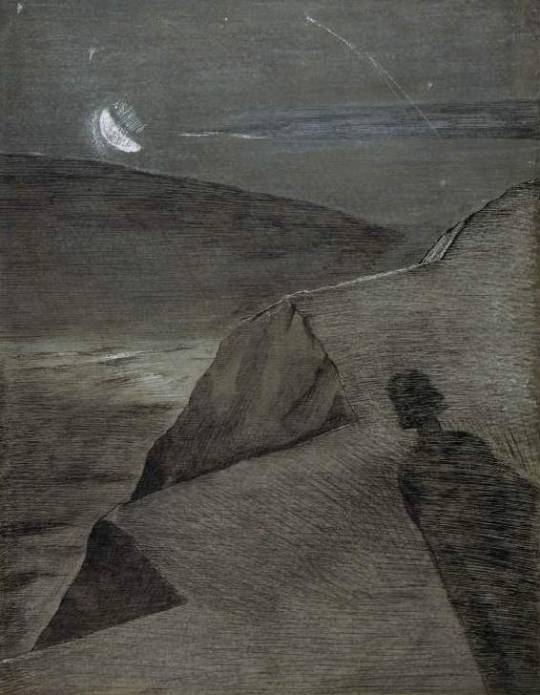

Paul Nash – The cliff to the north, 1912, Fitzwilliam Museum

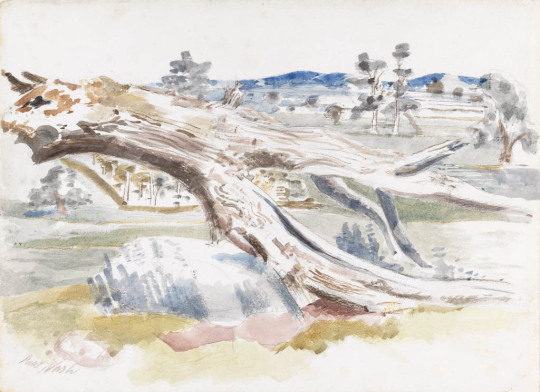

Below are a series of Monster Studies, the photographs and oil are in the Tate but the watercolours are in the Fitz. It is interesting to show how Nash used photography as a memory aid.

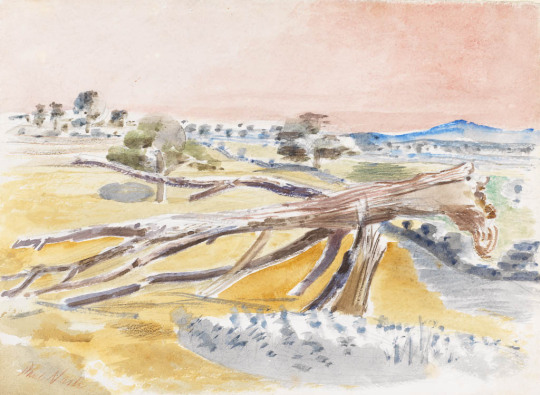

Paul Nash – Monster Field, Study I, 1938, Fitzwilliam Museum

Paul Nash – Monster Field, 1938, Tate TGA 7050PH/1111

Paul Nash – Monster Field, Study II, 1938, Fitzwilliam Museum

Paul Nash – Monster Field, 1938, Tate TGA 7050PH/1109

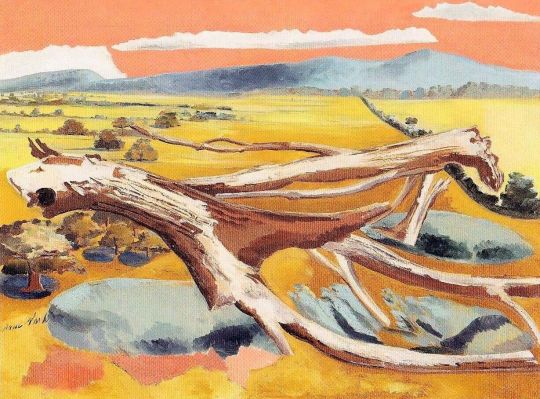

Here in the oil painting by Nash below, he uses both of the ‘Monster’ tree stumps, one in front of the other with his dream like landscape. If it wasn’t for the Oak trees, I would guess at it being Mexico, it’s almost a tacky colour palette.

Paul Nash – Monster Field, 1938

Paul Nash – Clouds, hill and the plain, 1945, Fitzwilliam Museum

Paul Nash – Sunset eye, Study II, 1945, Fitzwilliam Museum

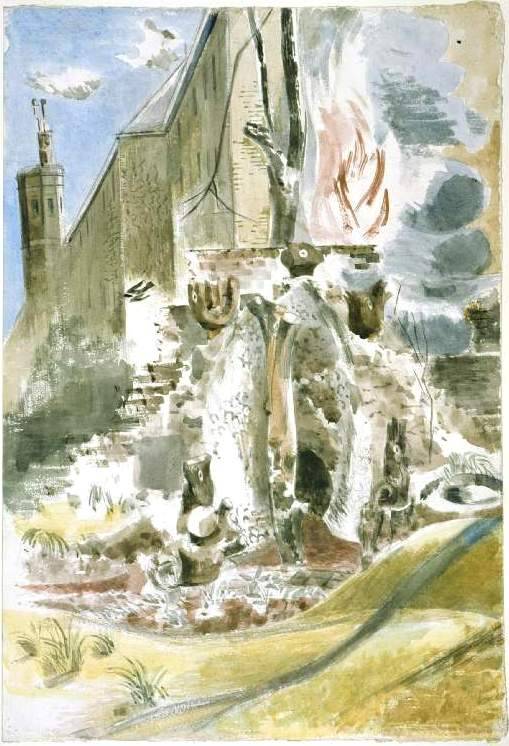

The photography returns with this other ugly Grotto made in the back-garden of Paul Nash’s house in 3 Eldon Grove, Hampstead. Nash lived at this address from 1936 till August 1939. In the photograph a tree stump has been placed in front of the grotto entrance in what might be said to be a phallic way.I don’t think anyone would have guessed this without the photograph as a guide as I thought his painting was of a semi demolished house.

Paul Nash – The grotto, Eldon Grove, 1938, Tate TGA 7050PH/670

Paul Nash – The grotto, Eldon Grove, 1938, Tate TGA 7050PH/673

Paul Nash – The Grotto at Eldon Grove / Study of the Grotto at Eldon Grove, 1938, Fitzwilliam Museum

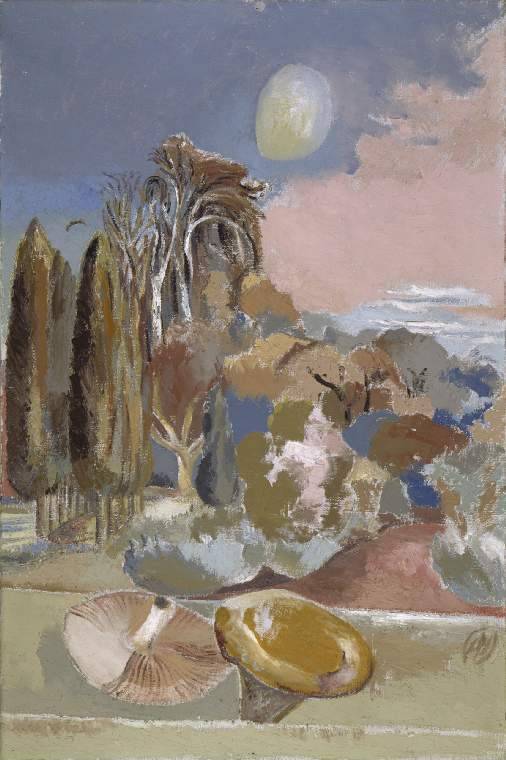

Paul Nash – November Moon, 1942, Fitzwilliam Museum

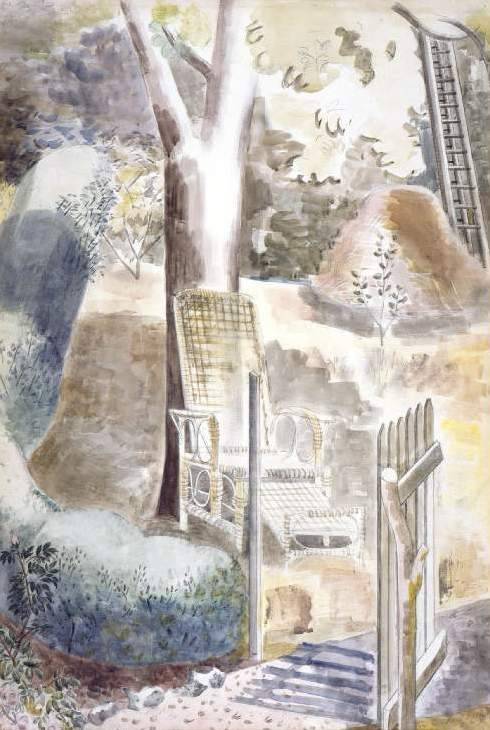

Paul Nash – Garden, 1929, Fitzwilliam Museum

Paul Nash – Atlantic ocean, 1932, Fitzwilliam Museum

Bright Cloud Sketch of a landscape, 1941, Fitzwilliam Museum

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Death Watch, Fitzwilliam Museum

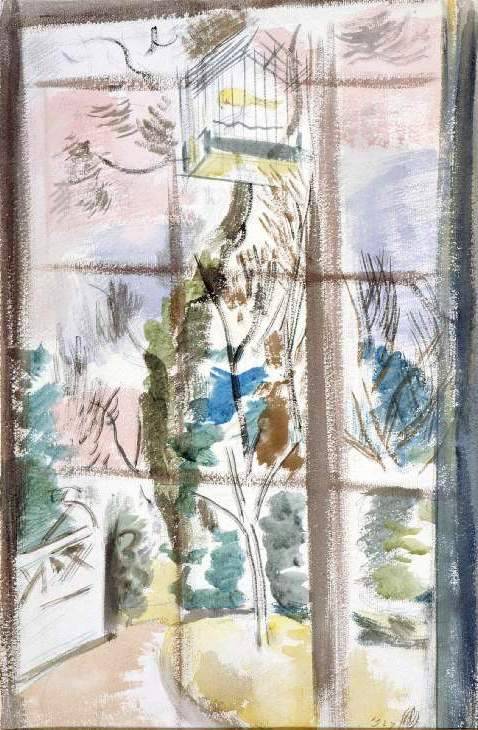

Paul Nash – The Bird-Cage (Canary), 1927, Fitzwilliam Museum

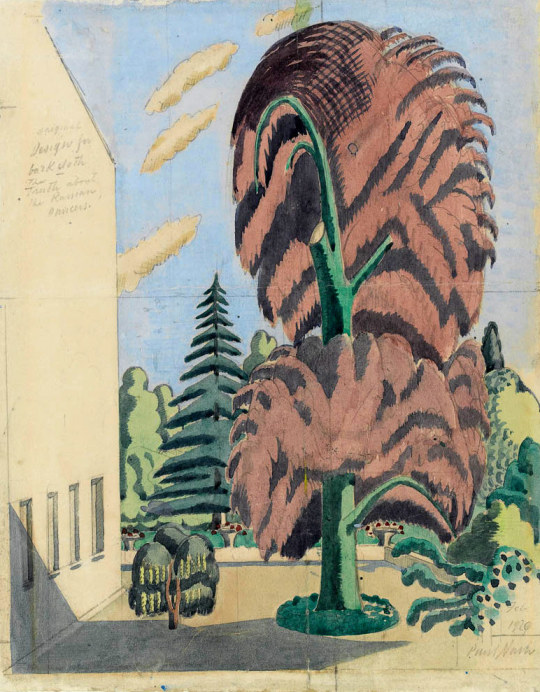

Paul Nash – Design for backcloth, The Truth about the Russian Dancers, 1920, Fitzwilliam Museum

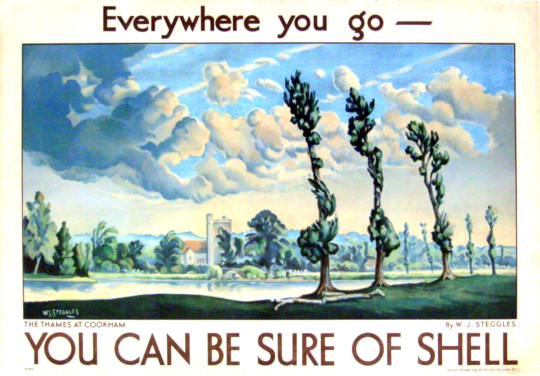

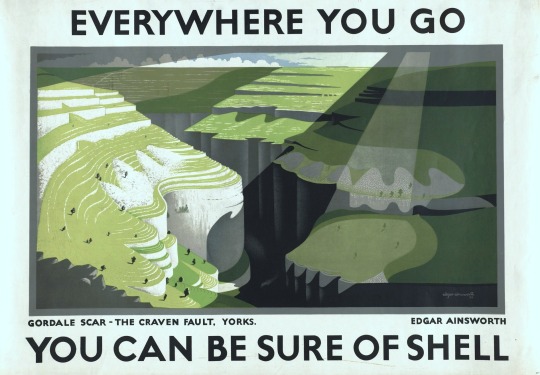

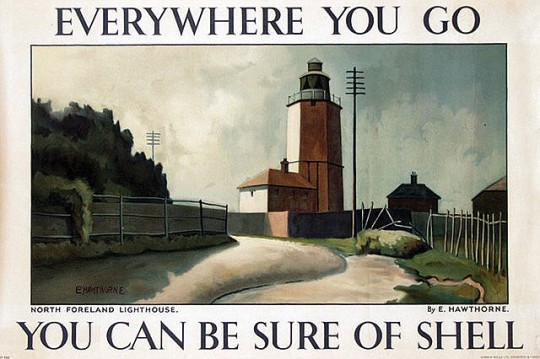

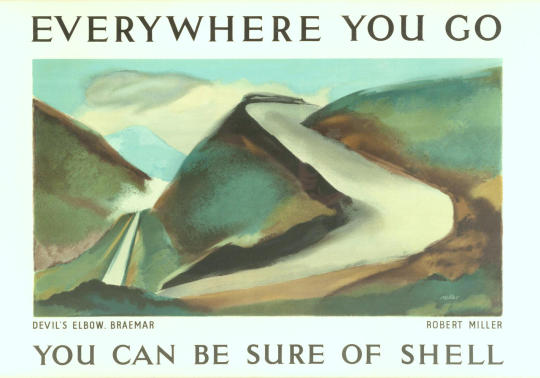

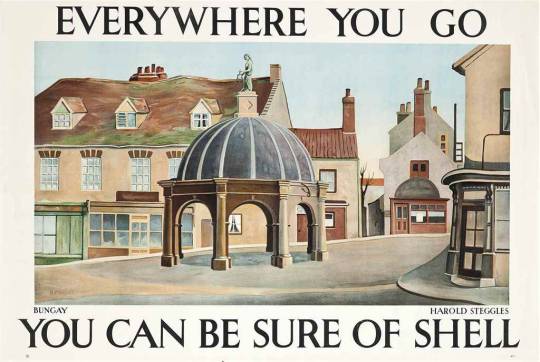

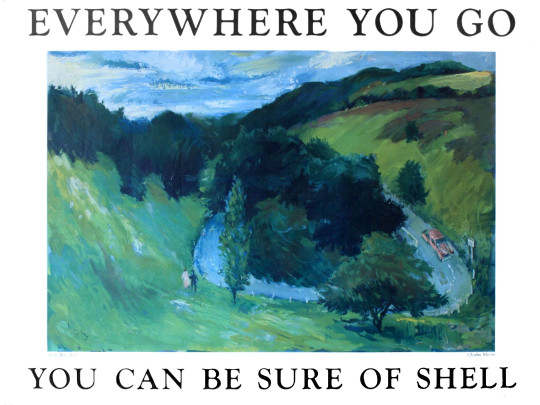

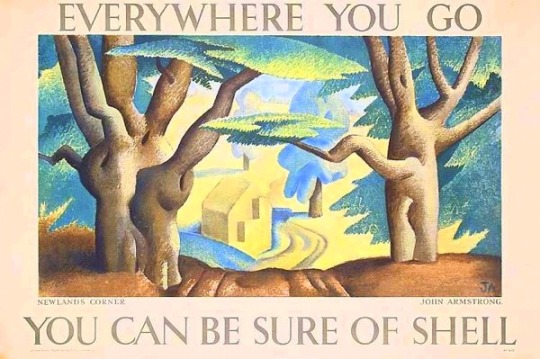

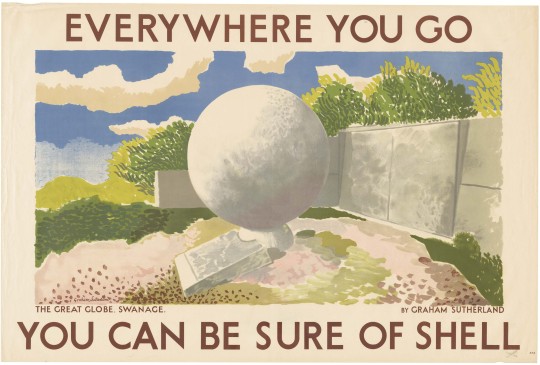

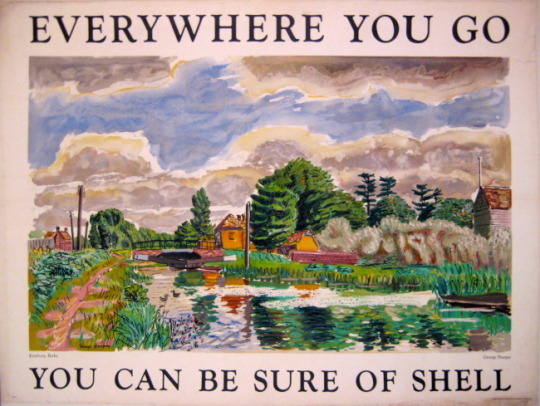

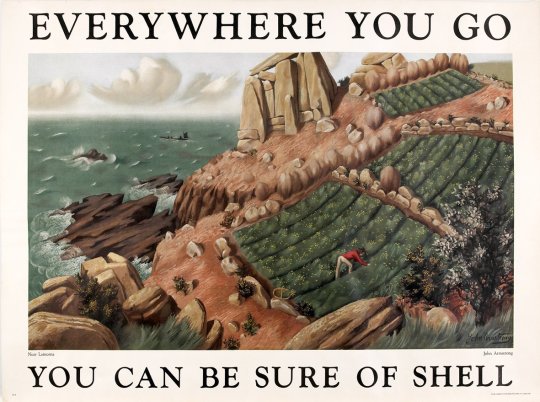

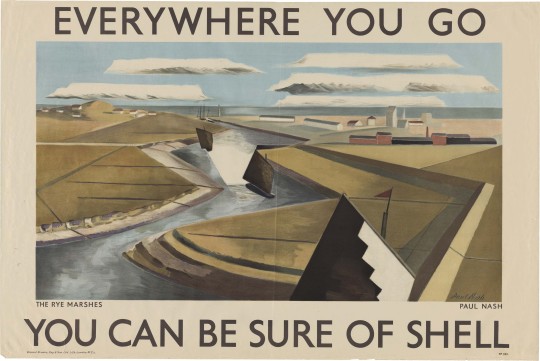

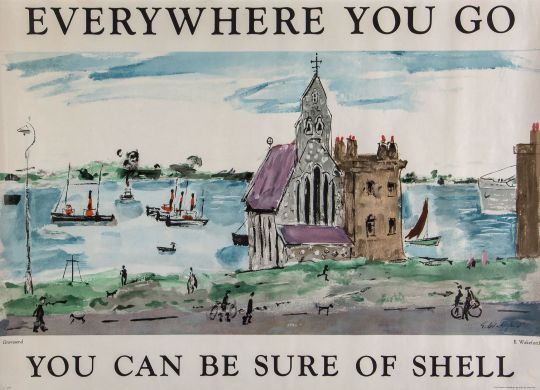

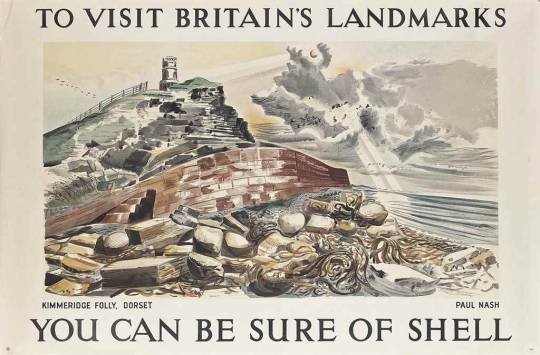

Both beautiful and inspiring, the artwork that Shell used on their posters was a shift in advertising for two reasons: They were selling the ambitions of the motorist beyond commuting; a generation of day-trippers without trains. Also they were presenting modern art to the public in an era when museums charged admission. The posters were pasted on the sides of petrol stations, lorries and billboards with that simple line “You Can Be Sure of Shell”.

Shell Mex Limited appointed a new Publicity Director in 1932, Jack Beddington. His insight turned the British Shell advertisements of the 1930s into one of the classic campaigns of the twentieth century. The genius of the campaign was to let artists depict Britain in their own styles, they would paint an image and whatever their style, it was surrounded by text. There would be no need for product placement, for models holding petrol cans, it was a campaign exposing the beauty and wonder of Britain and modern art.

Some of these posters were exhibited at the New Burlington Galleries in 1934. Below are two quotes from different reviews on the exhibition that show the surprise of critics to Beddington’s use of modern artists in poster design.

It is now a good many years since, under the able directorship of Mr Frank Pick, some of our best designers were encouraged to show their works in public – using the expression in its broadest sense. People who never though of going to picture galleries could, for the first time find delight in good pictorial art even in an Underground station and in the street. –

Apollo, January to June, 1934, p322 †

If it can be hoped that big firms like Shell-Mex are really going to patronize art as intelligently as this, we shall expect to be seeing in a few years’ time at Christie’s, not the sale of the collection of the Duke of Frumpshire, but of the Gas Light and Coke Company. If the princes of commerce are going to behave like princes we shall have some fun. ‡

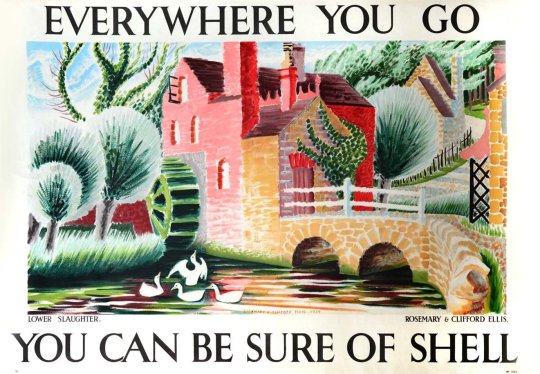

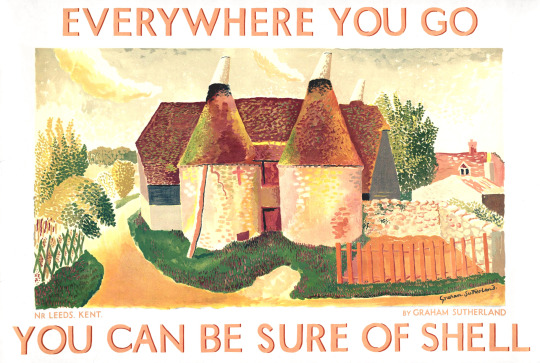

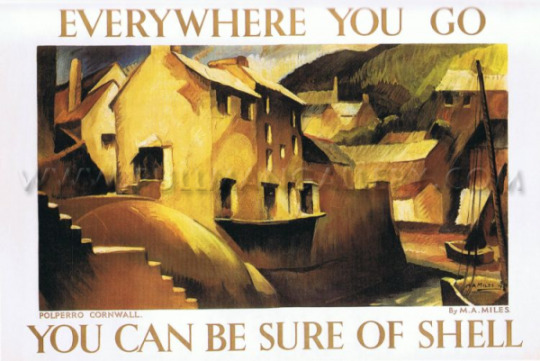

The Everywhere You Go series is one of the more curious for it is before the typographic design for the posters had settled down, a range of typefaces, colours and sizes are used. The first offering by W J Steggles has the tag line in lowercase. Steggles was part of the now fashionable, East London Group of artists, he painted various scenes for Shell posters, as did his brother Harold and

Elwin Hawrhorne.

Walter James Steggles – The Thames at Cookham

Edgar Ainsworth – Gordale Scar

Elwin Hawrhorne – North Foreland Lighthouse

Robert Miller – Devil’s Elbow, Braemar

Harold Steggles – Bungay

Rosemary and Clifford Ellis – Lower Slaughter

Graham Sutherland – Oust Houses nr Leeds, Kent

M. A. Miles – Polperro Cornwall

Charles Mozley – Boxhill

John Armstrong – Newlands Corner

Graham Sutherland – The Great Globe, Swanage

George Hooper – Kintbury Berks

John Armstrong – Near Lamorna

Paul Nash – Rye Marshes

Edward Wakeford – Gravesend

† Apollo, January to June, 1934, p322

‡ W.W.Winkworth – The Spectator – 29 JUNE 1934, p15

Catherine McDermott – Design Museum Book of Twentieth Century Design, 1998, p319

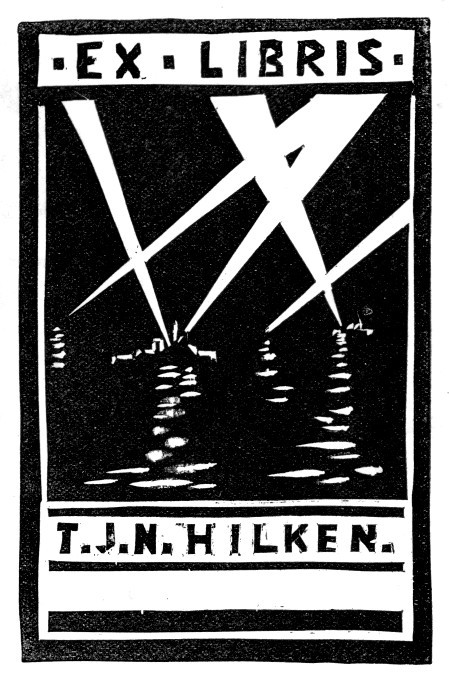

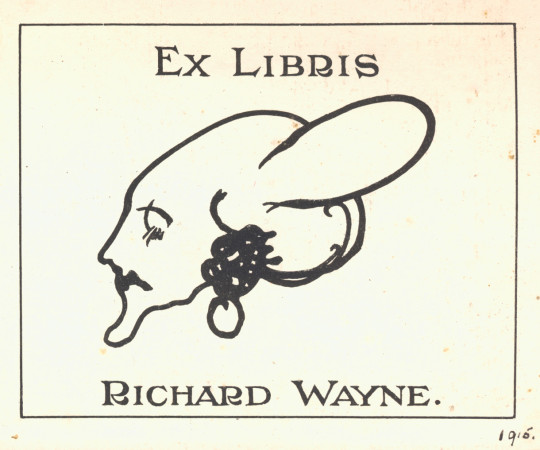

In the past week while looking at some of my books, I noticed that many of them have Ex Libris plates. I have not really thought of having such a thing myself. I always thought although decorative, in most cases they are dull and damage books – though it is nice to trace the possessions of people. Some of the bookplates you are able to Google the people involved, others it is a mystery.

Captain Thomas John Norman Hilken, DSO. (1901-1969)

Richard Wayne. The illustration is lovely and I thought slightly Bloomsbury but I couldn’t find any mention of him.

Stephen Brook

A Book Society bookplate for the public to fill in by Rex Whistler, below another design by Whistler, this time for Duff Cooper.

Trinity Hall Library, Cambridge

Keith Douglas – Second World War Poet.

Samuel Courtauld – Art Collector and founder of the Courtauld Institute of Art. Designed by Paul Nash.

John & Myfanwy Piper – Artists and writer.

Raymond Lister – Society Ironworker and writer on Romantic Watercolourists, designed by Reynolds Stone.

Brian M Warner. A mass produced bookplate by D.W who is unknown to me.

Trevor and Anne Martin

Hengrave Hall library bookplate. Hengrave Hall is a Tudor manor house near Bury St. Edmunds and has been a nunnery. It is now a wedding venue.

E G Crowsley.

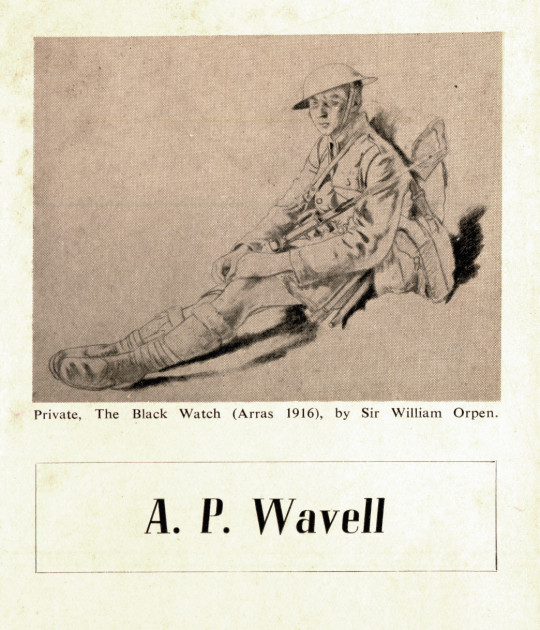

Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, GCB, GCSI, GCIE, CMG, MC, KStJ, PC. As noted on the plate, it features a beautiful drawing by William Orpen.

Angela Carter the Novelist.

One of the Prince Friedrich’s of Liechtenstein

John Denham Austin, writer. Figures depicted are Samuel Johnson and James Boswell.

Norbert Hardy Wallis – Translator and writer.

2nd Lieutenant in the South Wales Borderers.

Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert McDougall, of the McDougall’s Flour company. His daughter married Prince Andrew Alexandrovitch of Russia, eldest nephew of Tsar Nicholas II.

Paul Nash – Black and white negative, stone personage, Avebury, 1933

Paul Nash is one of the most distinctive and important British artists of the 20th century. He is known for his work as an official war artist during both WW1 and WW2. He also was one of the most evocative landscape painters of his generation. Nash was a pioneer of modernism in Britain, promoting the avant-garde European styles of abstraction and surrealism in the 1920s and 1930s.

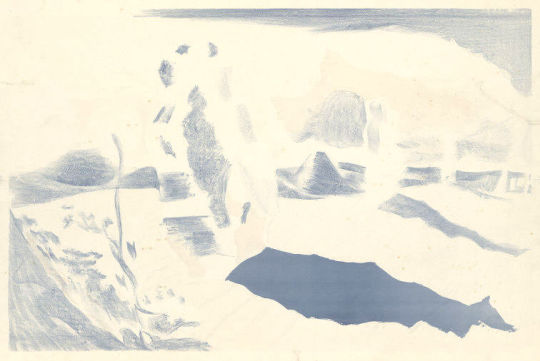

This post is about the printing process and how the Landscape of the Megaliths lithograph was made, showing each of the layers that were printed to make up the final image.

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Megaliths – Watercolour, 1937

Last summer I walked in a field near Avebury where two rough monoliths stand up, sixteen feet high, miraculously patterned with black and orange lichen, remains of an avenue of stones which led to the Great Circle. A mile away, a green pyramid casts a gigantic shadow. In the hedge, at hand, the white trumpet of a convolvulus turns from its spiral stem, following the sun. In my art I would solve such an equation. ‡

This lithograph by Nash is the bridge between romantic and surrealist art of the 1930s. Looking like a desert landscape by Dali the monoliths are both alien and familiar as Nash notes in the quote above. The convolvulus plant is a pernicious weed, I remember it covering a water-pump in the village I grew up in.

It is odd to consider that in my design I, too, have tried to restore the Avenue. The reconstruction is quite unreliable, it is wholly out of scale, the landscape is geographically and agriculturally unsound. The stones seem to be moving rather than to be deep-rooted in the earth. And yet archaeologists have confessed that the picture is a true reconstruction because in it Avebury seems to revive. ♠

Above is the original watercolour that Nash and the printers would have worked from. The colours have replaced and layered over shadow and texture. Below are many colour layers from the print showing the levels of tone and texture Nash would have used to put into the print. The main tones are printed one-by-one and then variations of tone are printed and layered, and the colours adjusted until the print is final. All the prints came from the V&A archive.

† Paul Nash by Emma Chambers, 2016

‡ The Oxford History of English Art, Volume 11 – Dennis Farr, 1979

♠ Paul Nash writing in Art and Education – March, 1939

Both beautiful and inspiring, the artwork that Shell used on their posters was a shift in advertising for two reasons: They were selling the ambitions of the motorist beyond commuting; a generation of day-trippers without trains. Also they were presenting modern art to the public in an era when museums charged admission. The posters were pasted on the sides of petrol stations, lorries and billboards with that simple line “You Can Be Sure of Shell”.

Edward Scroggie – Temple Bar

The respectability of motor touring was reinforced by the list of artists commissioned by Shell. It reads like a Who’s Who of the British art establishment of the period – Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, Vanessa Bell, Ben Nicholson, Rex Whistler and Edward McKnight Kauffer – who between them produced some of the finest examples of commercial art while promoting a nostalgic view of England at the same time. At this stage of the century the motor car itself was not perceived as a threat to the countryside. Buying a car meant buying into a new world. ‡

Richard Guyatt – Ralph Allen’s Sham Castle

Ralph Allen’s Sham Castle:

Ralph Allen was an entrepreneur, philanthropist and was notable for his reforms to the British postal system. He his home, Prior Park, a Palladian house, built to demonstrate the properties of Bath stone as a building material, Allen happened to own a few stone mines in Bath. On the crest of Bathwick Hill facing the city of Bath is the colloquially dubbed “Ralph Allen’s Sham Castle”, built in 1755. Guyatts poster is the most modernist in this post, making use of positive and negative line drawing in the shade and light.

Edward McKnight Kauffer – Dinton Castle, Near Aylesbury

Dinton Castle:

A most charming, innocent folly, standing on a little mound by the Aylesbury-Thame road and circled by pine trees. It was built in 1769 by Sir John Vanhatten to house his collection of fossils, some of which are let into the random rubble walls. The plan is a hexagon with towers at two opposite corners, one for fireplaces and the other for a spiral staircase. ♠

Graham Sutherland – Bringham Rock, Yorkshire

Bringham Rock, Yorkshire.

Sutherland visited this site in the autumn of 1935 at the suggestion of Jack Beddington, who wanted it to figure as one of a series of Shell posters. The result is a dreamlike lithograph, more in the style of Paul Nash. There are other rock structures on the site, all unique. ♣

There are many variations of rock formations, caused by Millstone Grit being eroded by water, glaciation and wind, some of which have formed amazing shapes. ♣

Paul Nash – Kimmeridge Folly, Dorset

Kimmeridge Folly, Dorset

When Paul Nash was working for Shell in 1937 it was to produce the Shell Guide of Dorset. He relocated for the project. His boss for the guide was not just Jack Beddington but also John Betjeman. It was Betjeman who suggested he paint Kemmeridge Folly for the ‘Landmark’s’ campaign. Paul Nash was paid 50 guineas when the picture was accepted as a poster in 1938.

Denton Welch – Hadlow Castle, Kent

Hadlow Castle, Kent

The first few months of 1937 saw Denton working on a large-scale panel of Hadlow Castle, a building some three miles east of Tonbridge. Although the main part of the house dated from the end of the eighteenth century and had been inspired by Strawberry Hill, the 170-foot tower, built between 1938-40, was modelled on William Beckford’s Fonthill. The whole ambience of the place appealed greatly to Denton’s love of the Gothic. His naive painting, which shows the puny tower rising above the other parts like a coffee-iced wedding cake, was designed specifically to be reproduced as a poster. †

Hadlow Castle was built on the site of Hadlow Court Lodge, a country house. The Castle was built over a number of years from the late 1780s, commissioned by Walter May in an ornate Gothic style, it became known as May’s Folly. The architect was J. Dugdale.

His son, Walter Barton May inherited the estate in 1823. It was he, who added a 170 feet (52 m) octagonal tower in 1838, the architect was George Ledwell Taylor. The tower was based in part on James Wyatt’s at Fonthill Abbey. A 40 feet (12 m) octagonal lantern was added two years later in 1840 and another smaller tower was added in 1852. This was dismantled in 1905. Walter Barton May died in 1858 and the estate was sold.

The property passed from many owners in the early twentieth century. During the Second World War it was used as a watchtower by the Home Guard and Royal Observer Corps. The unoccupied castle changed hands several times after the war too, until it was demolished in 1951, except for the servants’ quarters, several stables and the Coach House, which was saved due to campaigning from the society portrait painter and local resident, Bernard Hailstone. The Tower was Listed as a historic structure on 17 April 1951.

† Denton Welch: Writer and Artist by James Methuen-Campbell, 2003

‡ The English Landscape in the Twentieth Century by Trevor Rowley 2006

♠ Follies & Grottoes by Barbara Jones, 1953

♣ Wikipedia: Brimham Rocks

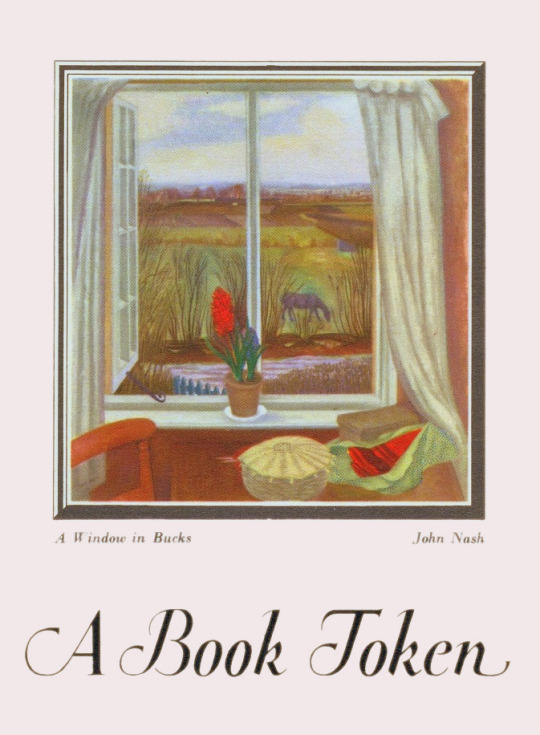

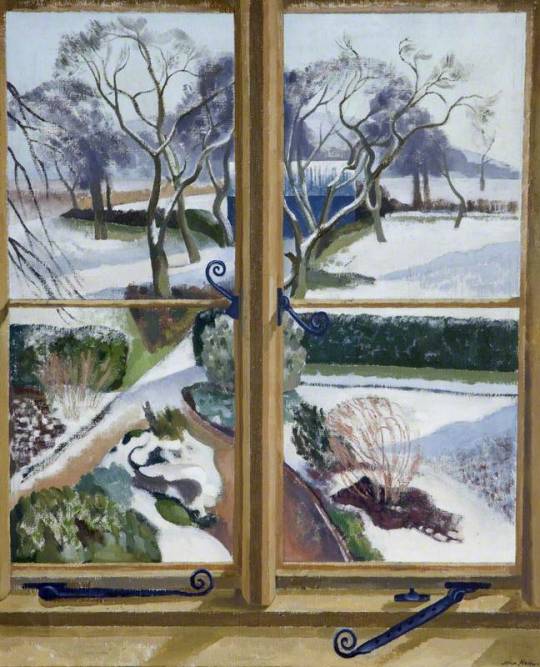

This week’s post all started with a book token that I found being used as a bookmark. It was of the John Nash painting ‘A Window in Bucks’.

John Nash – A Book Token featuring A Window in Bucks

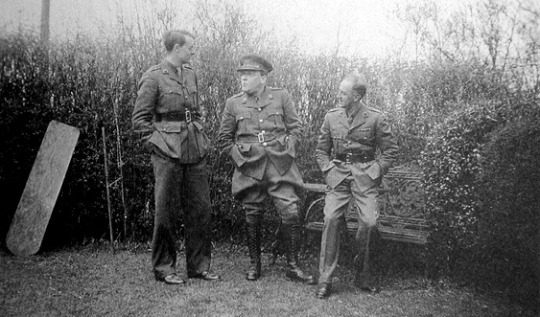

The painting was a view from John Nash’s house ‘Lane’s End’ in Meadle, Buckinghamshire. John Nash and his wife Christie moved to the village in 1922 and stayed until 1939. During his time there many friends visited including Eric Ravilious, Barnett Freedman and his brother Paul Nash.

Eric Ravilious, Barnett Freedman and John Nash photographed by Christie Nash in April 1940. †

Meadle is a hamlet in Buckinghamshire, England. It is located to the north of the village of Monks Risborough and near Little Kimble. Today the population of Meadle is about 75. A village of barn conversions and very few new housing, most of the properties are farmhouses and labourers’ cottages build in traditional red clay brick with thatched roofs. A small stream rises in the village and ultimately joins the Thames.

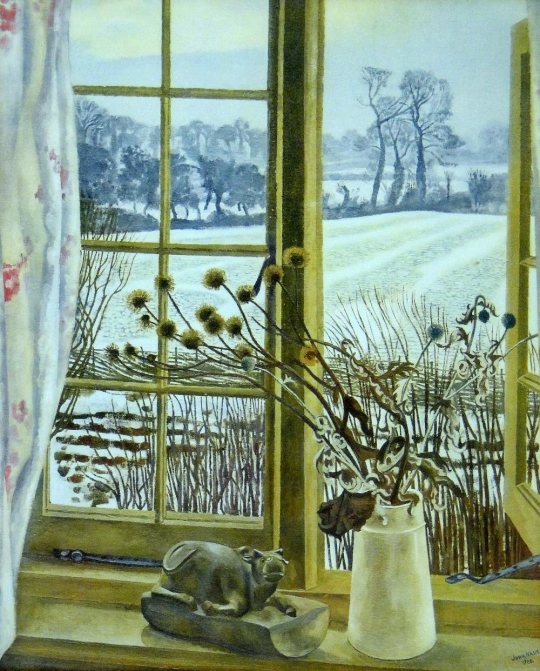

The view of the book token is taken from the window at Meadle, The same view can be seen from the painting below.

John Nash – Winter Landscape

The field line of this painted study line up to the bookplate above, the shape of the hedges and the three colours in the fields too.

John Nash – Window in Bucks, auto-lithograph, 1928.

In this lithograph the view out of the window is to the left-side, but still lines up with hedgerows today. What some have called ‘willow style fencing’ is actually a traditional hedgerow of what is most likely Hawthorn.

John Nash’s home ‘Lane’s End’, Meadle, Buckinghamshire.

One of the upstairs windows at the front of the house would have been where the paintings where made as the hedgerows in the painting line up to the hedges and field layouts today.

Paul Nash – Lupins and Cactus, 1928

The painting Lupins and Cactus is believed to have been painted by Paul Nash while staying at Meadle in 1928. The windows fit the style painted in the house and the flowers are likely to have been grown by John in the garden.

John Nash – The Garden under Snow

The Garden under Snow is believed to be a view from the back of the house and the garden of Lane’s End

† Ravilious: The Watercolours By James Russell