Avebury is a Neolithic henge monument containing three stone circles. The Village of Avebury in Wiltshire was built around them and now bisect the circle with a High Street. Avebury contains the largest megalithic stone circle in the world. Constructed over several hundred years in the Third Millennium BC, during the Neolithic, or New Stone Age, the monument comprises a large henge (a bank and a ditch) with a large outer stone circle and two separate smaller stone circles situated inside the centre of the monument.

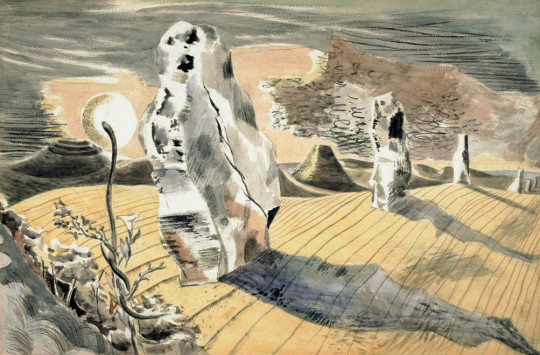

Paul Nash – Avebury, 1936

When England was converted to Christianity, Avebury was considered a non-Christian monument. At some point in the early 14th century, villagers began to demolish the monument by pulling down the large standing stones and burying them in ready-dug pits at the side. During the toppling of the stones, one of them (which was 3 metres tall and weighed 13 tons), collapsed on top of one of the men pulling it down, fracturing his pelvis and breaking his neck, crushing him to death. Trapped in the hole that had been dug for the falling stone he was found by archaeologists in 1938. They found that he had been carrying a leather pouch, in which was found three silver coins dated to around 1320–25, as well as a pair of iron scissors and a lancet.

In the latter part of the 17th and then the 18th centuries, destruction at Avebury reached its peak. The majority of the standing stones that had been a part of the monument for thousands of years were smashed up to be used as building material for the local area. This was achieved in a method that involved lighting a fire to heat the sarsen, then pouring cold water on it to create weaknesses in the rock, and finally smashing at these weak points with a sledgehammer.

In the 1920s Marconi wanted to build a radio station on the hills above Avebury and the Air Ministry wanted to close Wayland Smithy area with standing stones as a bombing range in the 1930s . †

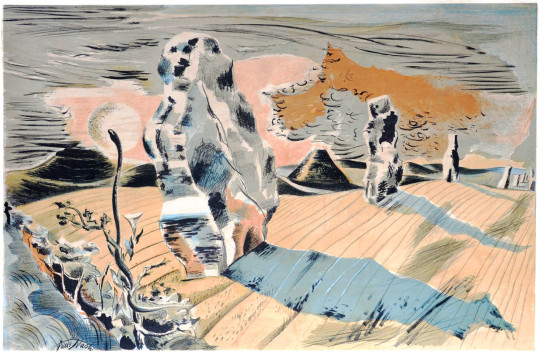

Paul Nash – Avebury, Personage, 1933

In July 1933 the ailing Nash went on holiday to Marlborough with his friend Ruth Clark. From there they made a day trip to nearby Avebury. ‡

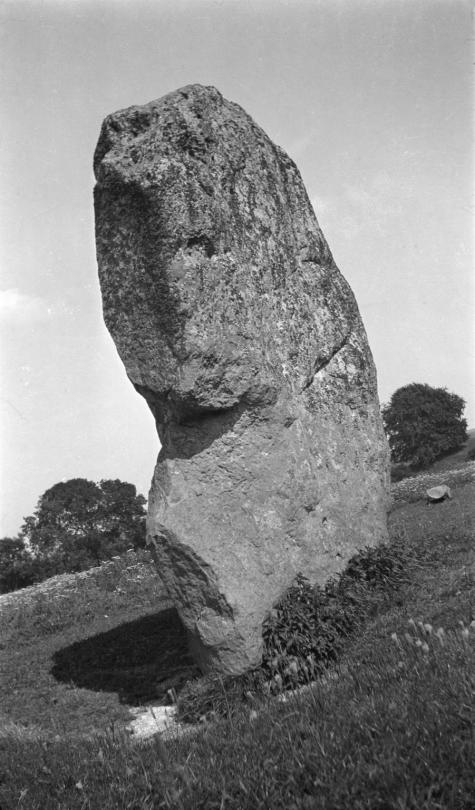

Paul Nash – Avebury Stone (Double Exposure), 1933

The epiphany that Paul Nash had to use he standing stones artistically, seems to have come with an interest in the Neolithic period in publishing with the British Public. It is an era where Paganism has become popular, as many alternative religions did after the First World War. In trying to make sense of the carnage and brutality of the War the public looked for ancient wisdom and this maybe why we have to tolerate people smothering themselves over Stonehenge every solstice.

In these paintings and photographs Nash was also documenting an interest that other artists such as Henry Moore had in the primitive. Moore looked towards early Peruvian pottery and flints for organic shapes and old works made by early man. These monuments are the few examples of art that survive. Even in the medieval period the only arts to survive in Britain of the common man would be the carvings of bench-ends in churches, pottery or other folk art.

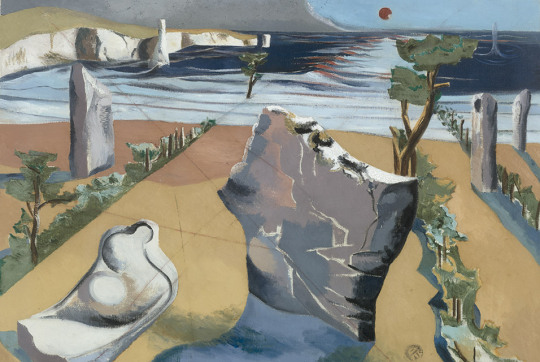

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Megaliths, 1934

Margaret Nash said this was Paul’s first painting of the Avebury stones, which he saw in August 1933. Nash himself gave the following description of Avebury in ‘Picture History’ The preoccupation of the stones has always been a separate pursuit and interest aside from that of object personages. My interest began with the discovery of Avebury megaliths when I was staying at Marlborough in the Summer of 1933. The great stones were then in their wild state, so to speak. Some were half covered by the grass, others stood up in the cornfields were entangled and overgrown in the copses, some were buried under the turf. But they were always wonderful and disquieting, and, as I saw them then, I shall always remember them … Their colouring and pattern, their patina of golden lichen, all enhanced their strange forms and mystical significance. Thereafter, I hunted stones, by the seashore, on the downs, in the furrows. ♣

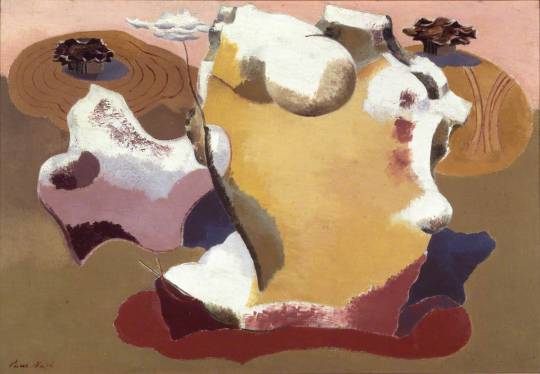

Paul Nash – The Nest of Wild Stones, 1937

I found my first nest of wild stones on looking closely into a drawing I had made of some bleached objects on the Swanage Downs. It lay just below the level of my consciousness, slightly out of focus. But there was no mistaking its lineaments a moment later when I moved the dry thoughts to one side. ♠

Below Paul Nash writes of the effect of Avebury on his work. That he wasn’t only painting the stones themselves but placing ordinary stones he found in a picture as if they were large monuments.

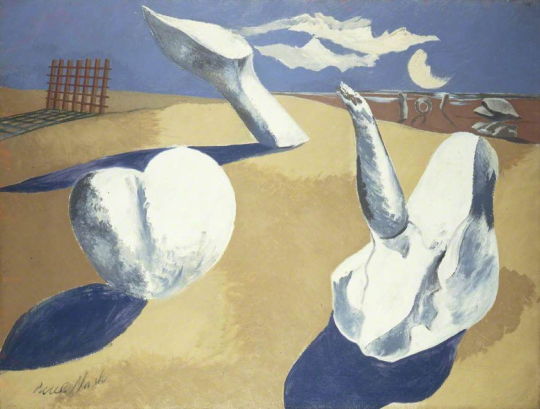

In most instances, the pictures coming out of this preoccupation were concerned with stones seen solely as objects in relation to the landscape. But later certain stone personages evolved, such as the stone birds in the ‘Nest of Wild Stones’ and the more ‘abstract’ forms in ‘Encounter in the Afternoon’. ♣

Many of these works may be down to another external influence, Eileen Agar. Nash had met and fallen in love with Agar, who was a surrealist artist and using stones and found objects in her works around the same time.

Paul Nash – Photograph of Stones in his Studio, 1936

Paul Nash – Encounter in the Afternoon, 1936

Paul Nash – Landscape of Bleached Objects, 1934

Paul Nash – Circle Of The Monoliths, 1937-8

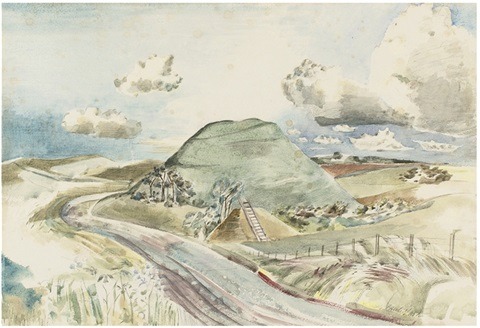

In the painting above (Circle of the Monoliths) is the stepped hill what is likely Silbury Hill. The construction of the hill in the Late Neolithic period was originally stepped, then filled in. Silbury Hill is very close to Avebury.

When the artist Paul Nash first visited Avebury in 1933 he was amazed by the scale of Silbury Hill and by the ancient circle of megaliths, the great glacial boulders that had been dragged from the Downs in prehistoric times. ♥

Paul Nash – Silbury Hill, 1938

Paul Nash – Silbury Hill, c1937

All Nash’s other statements about Avebury and stones are much more direct, it is almost as if he contrived to intellectualise his ideas simply to be provocative, but in face the Landscape of the Megaliths Nash does resolve the equation. The picture shows the adventure of stones receding away from the spectator, in the foreground in the convolvulus curls round a snake which rises upwards. ♦

Paul Nash – Avebury Stone, 1933

The stones at Avebury come up again when Nash was asked to illustrate a cover to the magazine Countrygoing. Though I think it was commissioned in 1938 it was published in 1945.

A Paul Nash Cover to Countrygoing, 1945

Paul Nash – Circle Of The Monoliths, 1937-8

Above is the finished painting of Circle Of The Monoliths. Below is the study for the work that was found painted on the back of The Two Serpents c 1937.

Paul Nash – Circle of the Monoliths, 1937-1938

Nash’s abstraction of stones in the 1930s went on with his distortions of landscapes, found stones and the real Neolithic stones. In we see Mên-an-Tol and the stone ring there placed in the top right corner in front of more found stones. To the right is a grid that can only be echoing Encounter in the Afternoon and Circle Of The Monoliths.

Paul Nash – Nocturnal Landscape, 1938

Below we see the same Avebury stone used on the cover to Countrygoing with the wedge shaped cut in the side.

Paul Nash – Druid Landscape, 1938

Initially, using a No.1A pocket Kodak series 2 camera, Nash captured images so that he could refer to them in the creation of his paintings. Increasingly, however, he saw his photographs, not as aids or sketches, but as artworks in their own right.

Here Nash depicts one of the Avebury Sentinels, and his choice of subject matter is characteristic. Nash was always interested in landscapes and aspects of the natural world, not for their historical or aesthetic interest per se, but more because he thought that certain places as he called them (see Biography) had about them a mystical importance, a genius loci; which lent the place, the stone, the tree, an importance which transcended its apparent properties. As he wrote there are places whose relationship of parts creates a mystery, an enchantment. It is this mystery, this enchantment, which Nash tries to capture in his photographs. ◊

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1933

Some of the quote below may be a repeat of what has been read about Nash, but I featured it for the Convolvulus park that features in Landscape of the Megaliths. In the background of the watercolour and lithograph below are two hills, both likely to be a Neolithic Sidbury Hill and how it looks today.

Last summer I walked in a field near Avebury where two rough monoliths stand up … miraculously patterned with black and orange lichen, remnants of the avenue of stones which led to the Great Circle. In the hedge, at hand, the white trumpet of a convolvulus turns from its spiral stem, following the sun. In my art I would solve such an equation

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Megaliths – Watercolour, 1937

Some time ago I made a blog post on Paul Nash and the process of colour layers used to make the lithograph below.

Paul Nash – Landscape of the Megaliths – Lithograph, 1937

The photographs below are dated 1942 by the Tate. I don’t know is Nash went back to Avebury or if they are catalogued wrongly. But I thought it was worth including them with the car by the roadside.

Paul Nash – Avebury, 1942

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1942

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1942

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1944

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1944

Paul Nash – Avebury, Sentinel, 1944

Paul Nash – Avebury, 1944

† Joanne Parker – Written on Stone: The Cultural Reception of British Prehistoric, 2009

‡ David Boyd Haycock – Paul Nash, p54, 2002

♠ Andrew Causey – Paul Nash: Writings on Art – Page 142

♣ Paul Nash – Paintings and Watercolours Exhibition Catalogue, Tate, 1975

♥ Julius Bryant – The English Grand Tour, p16, 2005

♦ Paul Nash, Places, South Bank Centre, 1989

◊ Art Republic