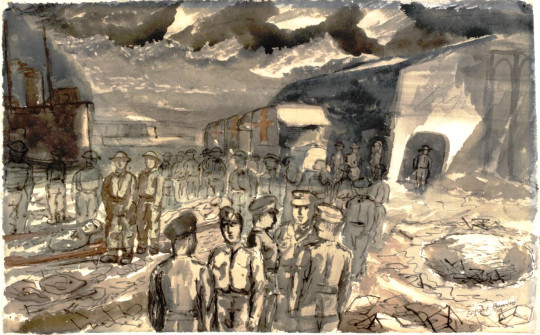

Nevinson caused a sensation with his one man exhibition of war paintings in 1916. The images presented the modern age’s first industrialized war, often in bold modernistic style derived from Futurism, and the pictures all sold. †

Nevinson’s artistic legacy in Britain had been established by his two exhibitions at the Leicester Galleries in 1916 and 1918. It was his work during this time, documenting the First World War that gave him some fame. The works at this time being a mixture of abstraction and futurism. When he first went to New York, it was as a war hero, a survivor and documenter of war in a bold new ‘futurist’ way.

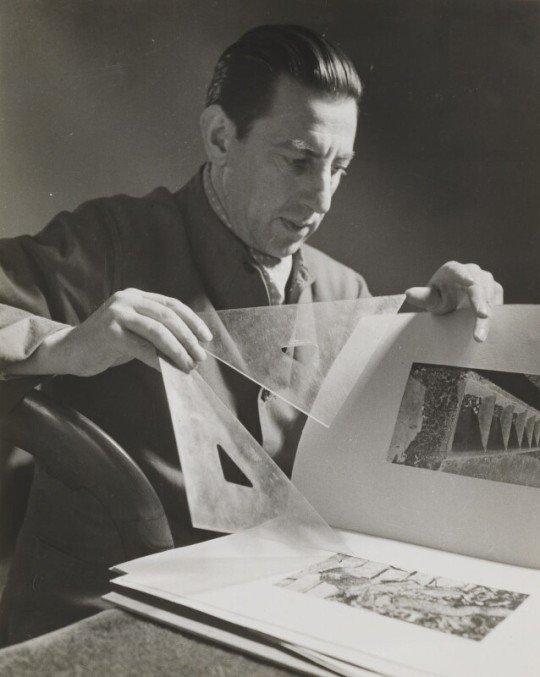

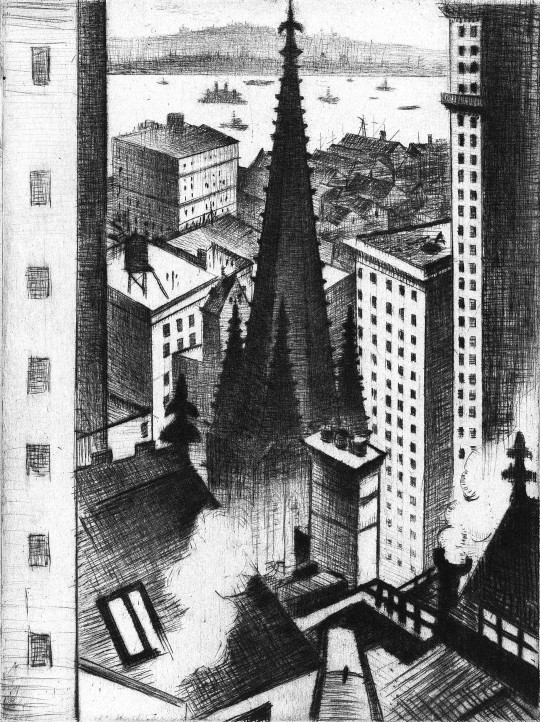

Nevinson was invited to New York in 1919 by David Keppel of the print publishers Frederick Keppel and Co, to exhibit his War prints. Manhattan’s architecture inspired him, not only by the sheer beauty of its skyscrapers. ♣

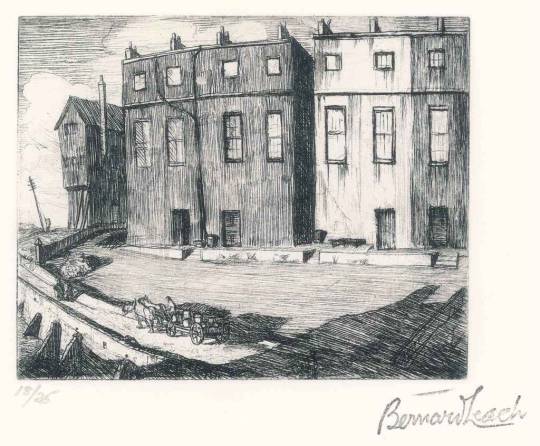

Nevinson made two trips to New York, the first in 1919 and again the following year. His first visit was to attend the exhibition of his war etchings and lithographs. This first exhibition held at Keppel and Co was a great success and the catalogue came with an introduction by the well known American critic and connoisseur Albert Gallatin.

It would have been during this first trip that Nevinson started a whole series of new works based on New York City. Many of these works were made from sketches and studies he made from the first trip, but were sold during his second. Many of the works are harder to date, a lot of the works are considered 1919/1920 but many of the dates rely on the year they were sold, not the year they were made. The process of lithography and etchings needed to be made in the studio later, some were sold at an exhibition in 1921. It is likely that many of the works that are etchings where also made into oil paintings(The Great White Way, Three AM), but their location is currently a mystery.

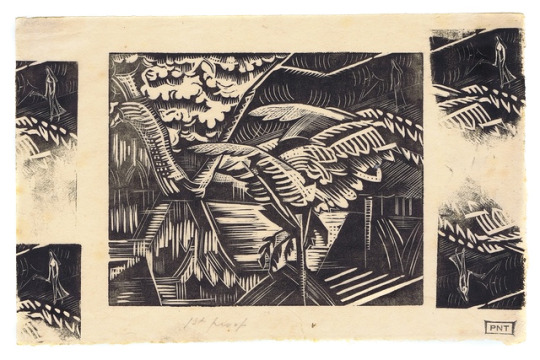

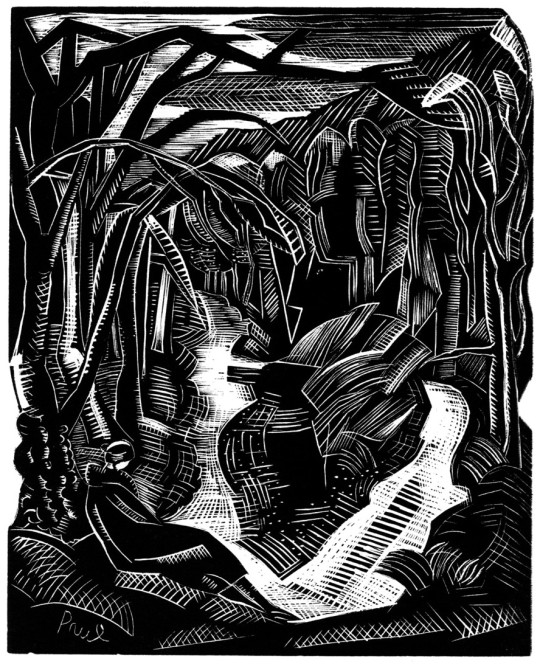

C.R.W Nevinson – Temples of New York, 1919 (Etching)

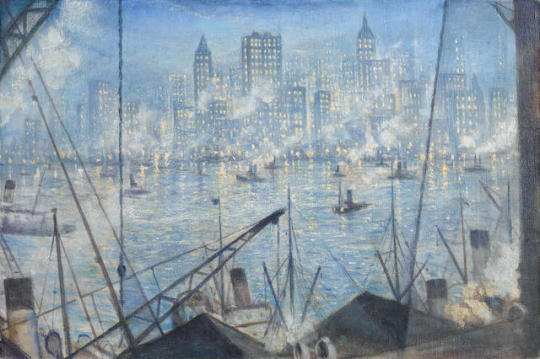

C.R.W Nevinson – The Statue of Liberty from the Railroad Club, 1919 (Oil)

C.R.W Nevinson – New York, Night, 1919 (Oil)

The print below ‘Looking down Wall Street’ has a view of the Brooklyn Bridge in the top left corner, though only 30 something years old at the time, the bridge and its size were still a marvel of engineering.

C.R.W Nevinson – Looking Down into Wall Street, 1919 (Lithograph)

He was clearly captivated by the city, compared to the London of the 1920s it must have been something, the skyscrapers of the time in New York would have been the Woolworth Building (60 stories) and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower (50 stories), but most of the ‘skyscrapers’ of the early 1920s peaked around 30 stories tall. London didn’t start building above 20 stories until the 1960s. Nevinson is quoted below:

‘New York, being the Venice of this epoch, has triumphed, thanks to its engineers and architects, as successfully as the Venetians did in their time.. Where the Venetian drove stakes into his sandbanks to overcome nature, the American has pegged his city to the sky. No sight can be more exhilarating and beautiful than this triumph of man. ♥

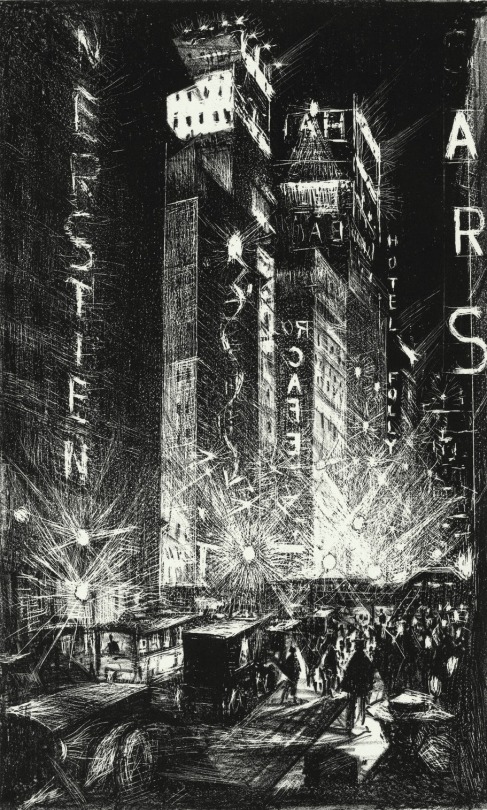

C.R.W Nevinson – The Great White Way, 1920 (Lithograph)

Between the New York exhibitions of 1919 and October 1920 Nevinson exhibited in the Senefelder Club – Leicester Galleries in February 1920 and also at the Manchester City Art Gallery in July 1920. The Great White Way was shown first at the Senefelder Club and Three AM shown first at Manchester.

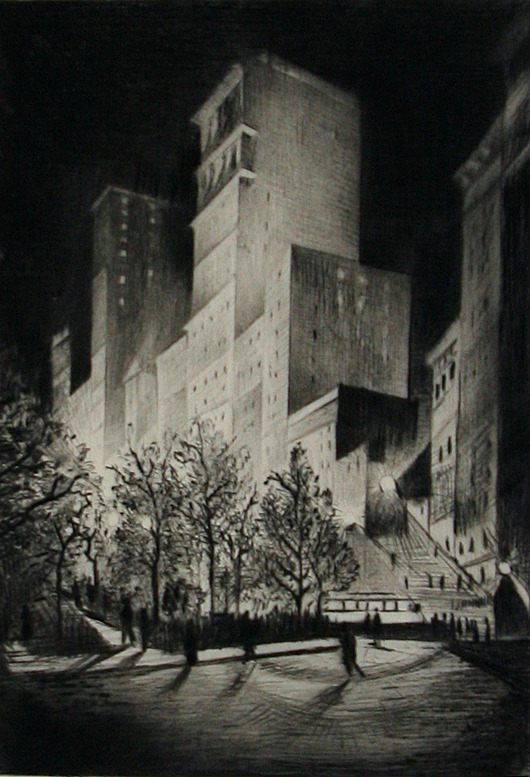

C.R.W Nevinson – Three A.M. – A Corner by Madison Square at Night. 1920 (Etching)

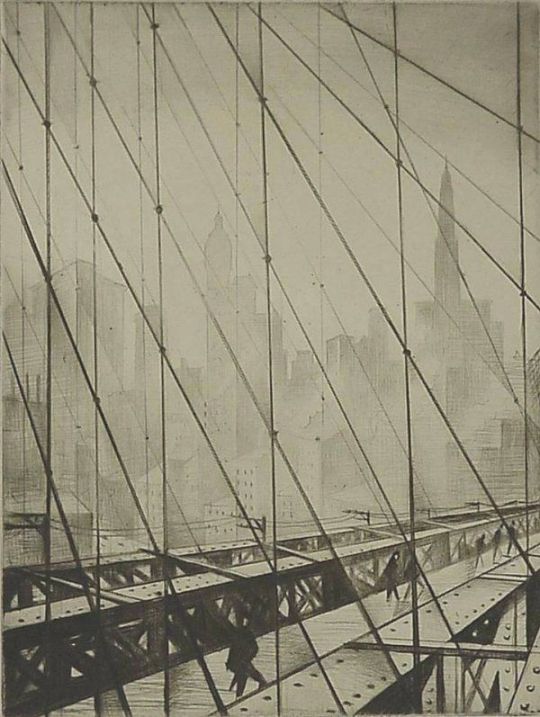

C.R.W Nevinson – Looking through Brooklyn Bridge, 1920 (Etching)

His second exhibition held at the Bourgeois Gallery was much larger, with a series of paintings and etchings of New York that failed to capture the attention of the public. The press were kind but the works did not sell well and there is little reporting of the second exhibition in comparison to the first. Nevinson hired a cuttings agency to collect all items about him that featured in the press.

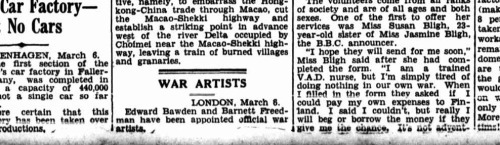

Below is an extract from the New York Herald, 24th October, 1920.

“Art,” says Mr. Nevinson, “triumphs in utility, and the most beautiful products of the modern world are a Rolls-Royce car and a skyscraper. They have been built for strict utility; their lines are perfect and they must appeal to the genuine artist. New York will be remembered for its introduction of the architecture of the skyscraper long after its people have been forgotten for other things.“ ◊

New York should like Mr. Nevinson and his work, for surely he is her friend. No native could ever idealize America’s greatest city more than this foreigner. ◊

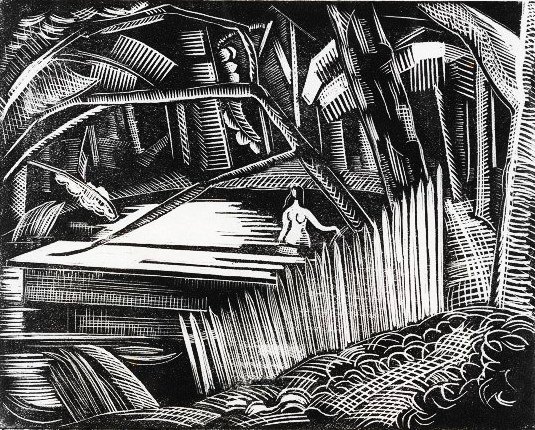

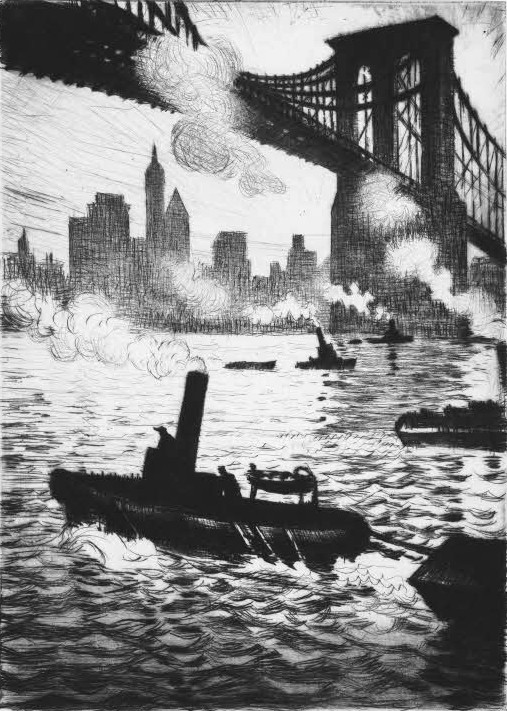

C.R.W Nevinson – Under Brooklyn Bridge, 1920 (Etching)

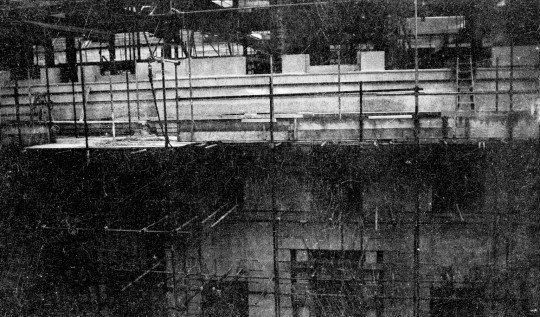

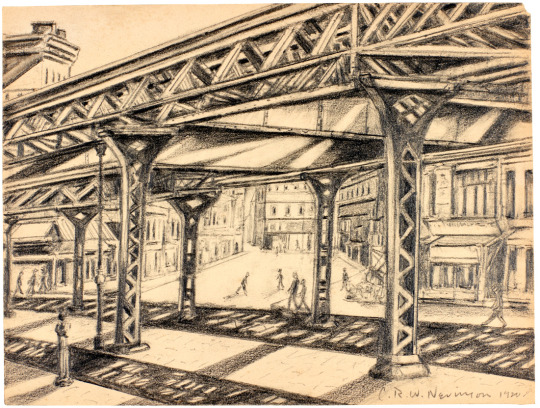

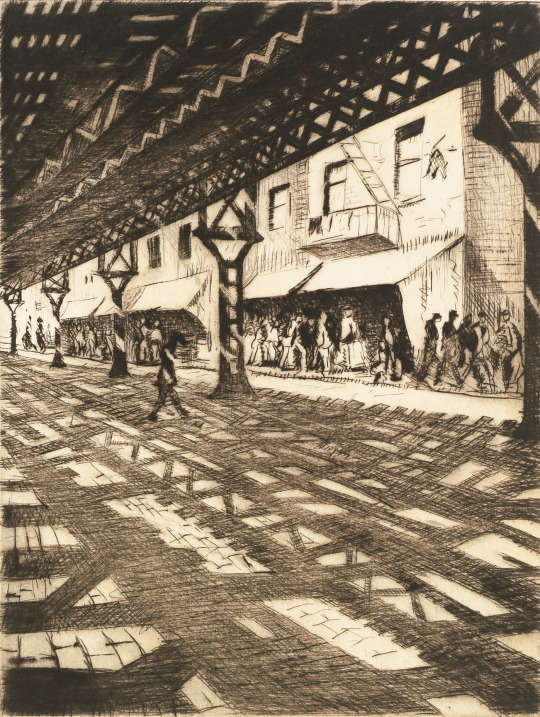

Here I start to look at the station and railway pictures. Here is a photograph of the Fulton Street Station and the Elevated railway. Railways like this started in London but were built of bricks with viaduct structures. In New York, the buildings were made of iron girders and so the railways were bridged with girders.

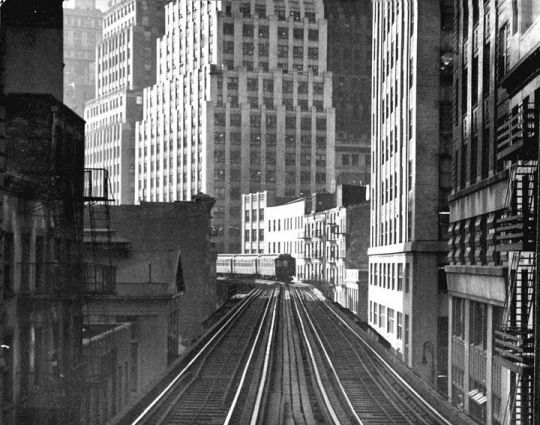

In a wonderful bit of research I found a photograph of the station at the intersection of Greenwich Street in Manhattan. When the railway line was taken down the World Trade Centre was built just to the left of this photograph.

Greenwich and Fulton Streets, 1914

The photograph shows the same view only 4 years before Nevinson stood in the same spot. Being able to pinpoint the location of the station has helped with the location of other works too.

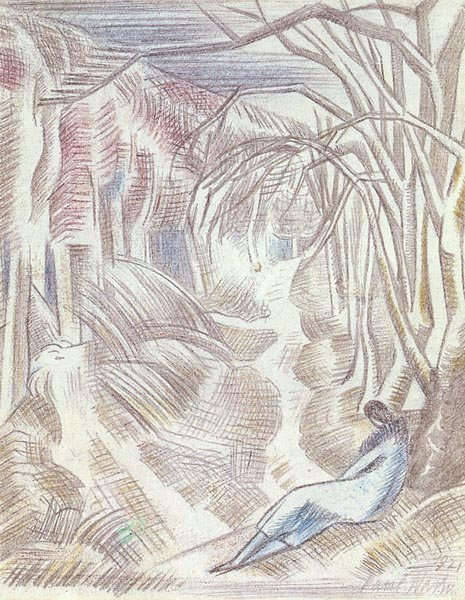

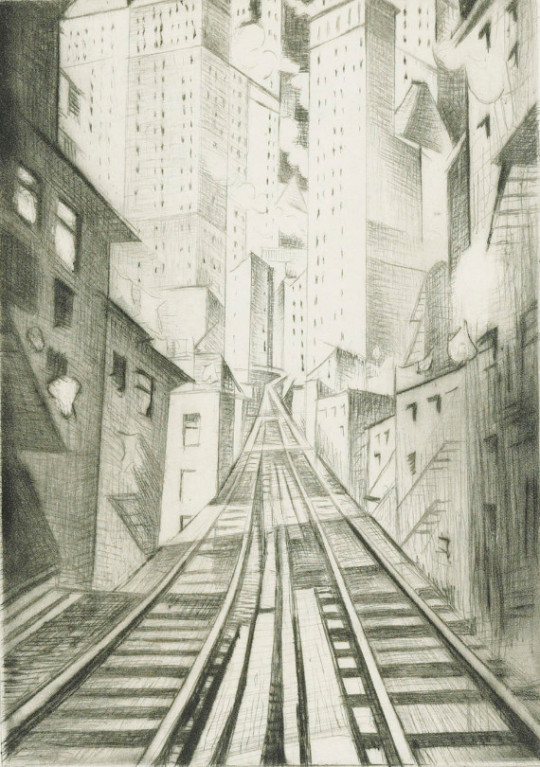

C.R.W Nevinson – Third Avenue, Elevated Railway, 1920 (Drawing)

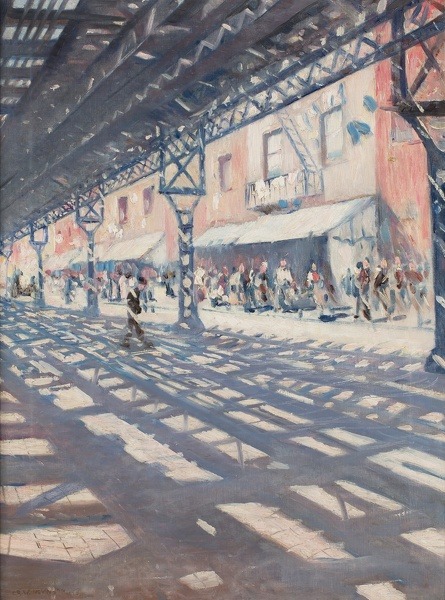

C.R.W Nevinson – Third Avenue, Elevated Railway, 1920 (Oil)

Critics have suggested that the almost Monet style of the oil painting Third Avenue, Elevated Railway is down to it being painted on the spot and not in Nevinson’s studio. The etching that would have been made later still has some of the free feeling that the painting has and is more pictorial and more photo accurate than many of his pictures are.

C.R.W Nevinson – Under the Elevated, 1921 (Etching)

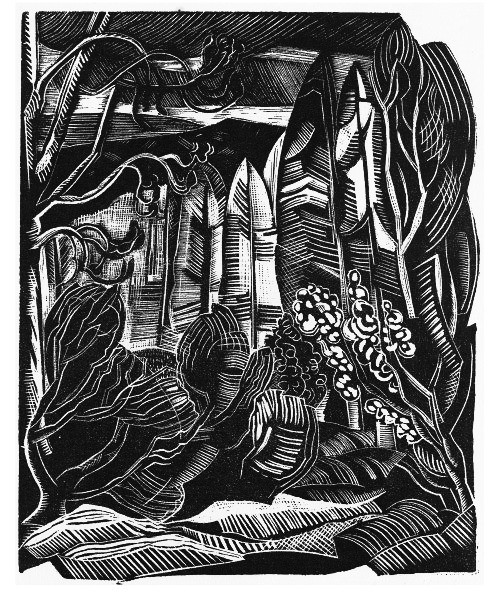

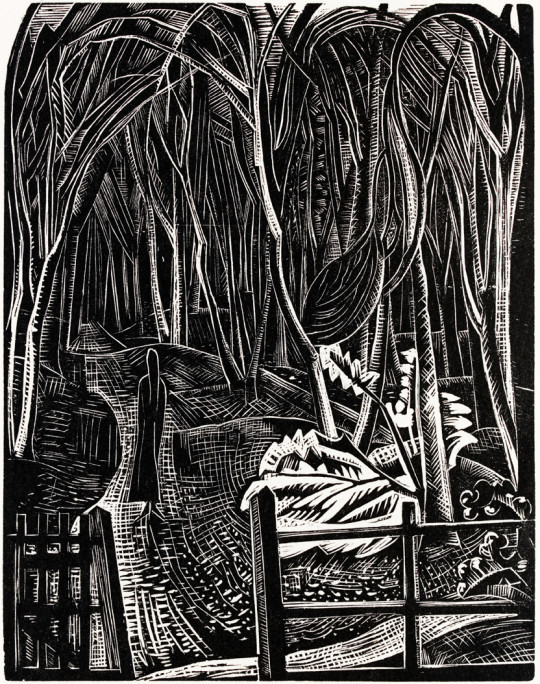

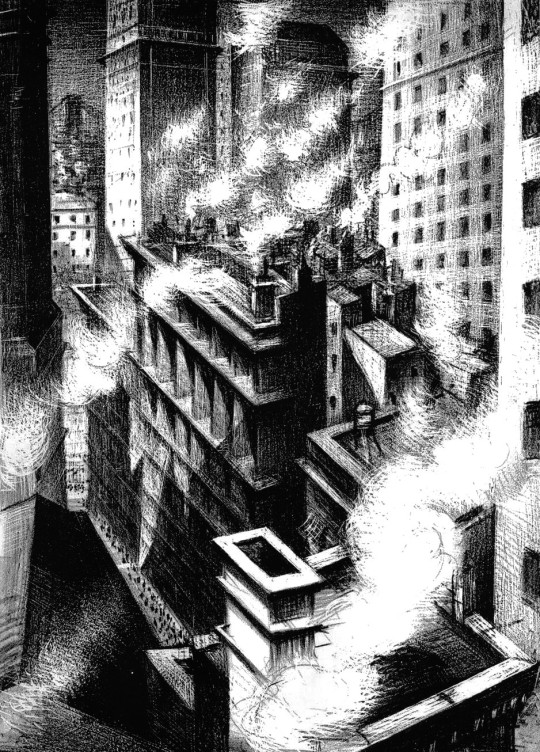

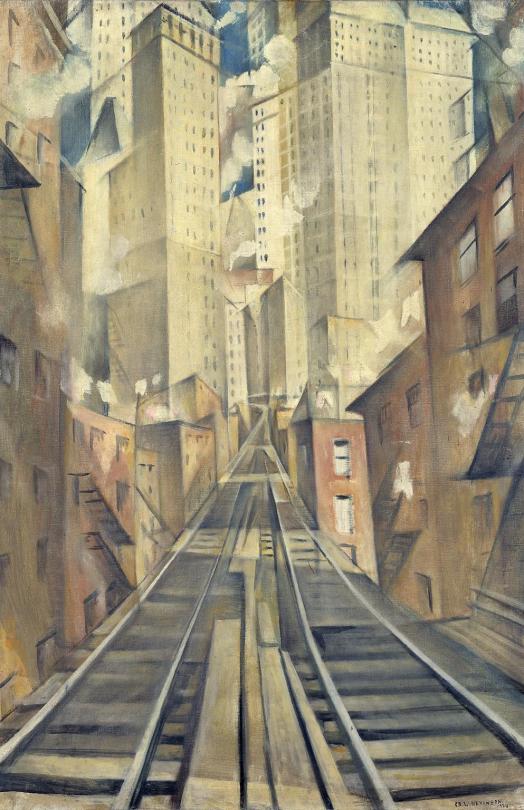

C.R.W Nevinson – New York: An Abstraction, 1921 (Etching)

C.R.W Nevinson – Fulton Station of 3rd Ave El, c1950

With the help of the drawing above and finding the location we can see that Nevinson was working in this part of New York on many views. The photo above is the same view as the etching above and the painting below. You can look at the metal fire escapes on either side of the buildings and find they match up. It is the view from the very end of the platform of the Fulton station. The skyscrapers become a theatrical fantasy.

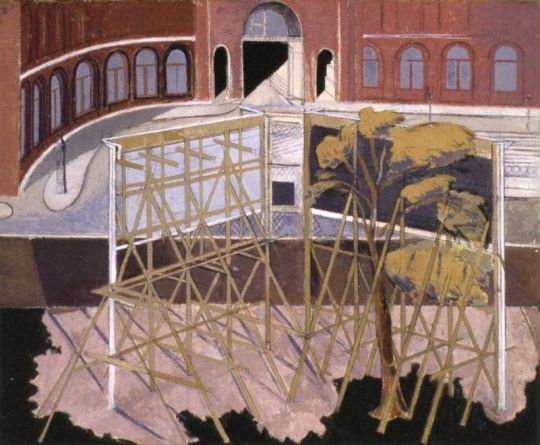

C.R.W Nevinson – The Soul of the Soulless City, Previously known as New York – an Abstraction ,1920 (Oil)

The poor reception of this exhibition may have accelerated Nevinson’s disaffection with the city. His growing embitterment is perhaps reflected by the change of title. Originally exhibited in 1920 at the Bourgeois Galleries, ‘New York, as New York – an Abstraction’, it was re-titled ‘The Soul of the Soulless City’ in the Faculty of Arts Exhibition, Grosvenor House, London, in 1925 probably at Nevinson’s instigation. ♦

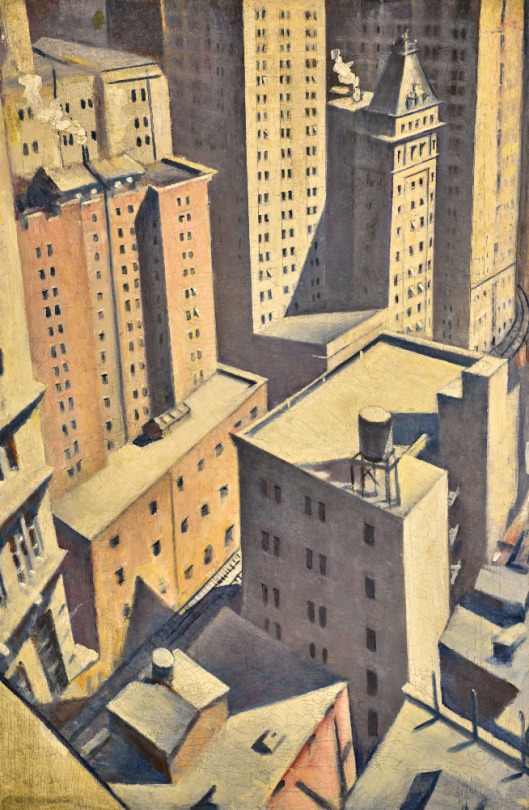

C.R.W Nevinson – Looking Down on Downtown, 1920 (Oil)

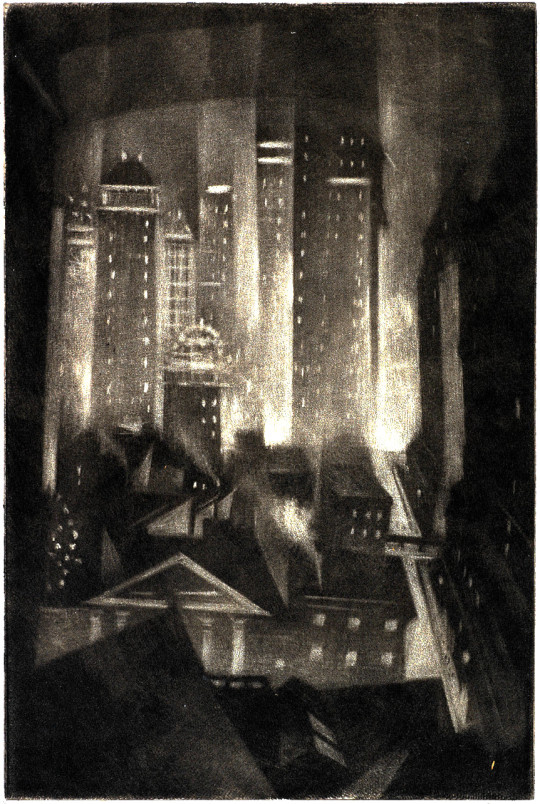

C.R.W Nevinson – New York, Night, 1920 (Mezzotint)

† Michael Walsh – A Dilemma of English Modernism: Visual and Verbal Politics in the Life and Work of C. R. W. Nevinson (1889-1946), 2007

♣ C.R.W. Nevinson 1889 – 1946 Retrospective Exhibition Of Paintings, Drawings And Prints: Kettle’s Yard Gallery 1988

♥ David Cohen – C.R.W. Nevinson, The Twentieth Century, p46, 1999.

◊ New York Herald, 24th October, 1920.

♦ Tate, London, T07448.