Here are some photos from walks and rides across Cambridgeshire.

Here are some photos from walks and rides across Cambridgeshire.

On the corner of the road into Cambridge, in Trumpington, is a very simple looking war memorial. Up close, you notice the detail and the figures. With no information or makers mark near-by you have to google the sculptor. In this case and rather unexpectedly it is by Eric Gill. Gill is remembered today as a typographic designer and sculptor, this most famous in Britain being Prospero and Ariel on Broadcasting House, London.

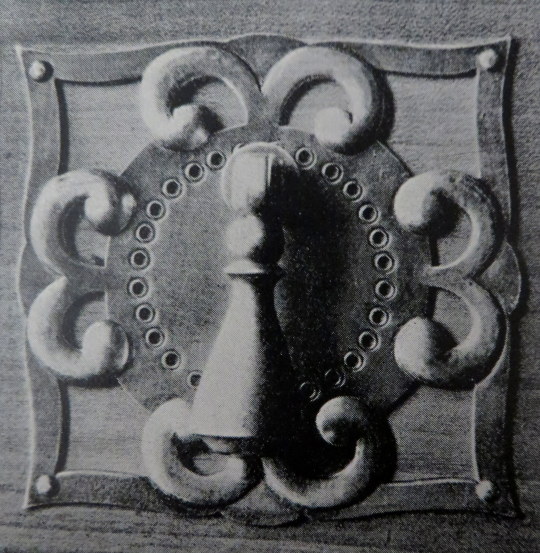

The four pictograph designs (an individual design for each side) for the Trumpington Cross are subtlety arranged at the base of the cross. Below that on the pedestal are Norman looking arches with the names of the fallen from WWII between.

For Trumpington, Cambridgeshire, he created a plain ‘cross of vaguely medieval form’ adorned with four small reliefs. One of the reliefs was based on a design by the author David Jones (like Gill a convert to Roman Catholicism), who had joined Gill’s radical ‘guild […] of craftsmen’ which sought to revive the communal spirit of medieval society. †

This was memorial was commissioned by the village itself, although the Pemberton family who owned Trumpington Hall has lost their son, Francis, in October 1914 and where the main donors to the village’s war memorial fun. The memorial cross that Gill designed was unveiled in 1921 and stands outside the gates of the hall. This spot was the most prominent corner of the village, on the junction of the village street and the main road to Cambridge.‡

It is the four images carved in relief on panels at the base of the cross which are so striking. Two of these represent religious subjects – St Michael triumphant in defeating the Devil, and the Madonna and Child (the parish church is dedicated to SS. Mary and Michael) – while the third depicts St George slaying the dragon. So far, so conventional. However, the fourth panel shows an exhausted soldier returning from the war, and this is one of the most profound, though least known, images of the experience of war to appear on any war memorial in Britain or Germany.‡

The Madonna and Child side below, seams to need some restoration as it’s weathering away.

The four sides of the shaft are inscribed with the names of 36 men from WWI and on the base a later addition of 8 men from WWII and what I believe is one from a subsequent war.

† The Great War and Medieval Memory: War, Remembrance and Medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914-1940

by Dr Stefan Goebel, 2007. 9780521854153 p.60.

‡ The silent morning (Cultural History of Modern War) by Trudi Tate, Kate Kennedy, 2015, 9781784991166 p.326.

Below is a piece on James Ravilious, written 20 years ago in ‘World of Interiors’, March 1996 by Ronald Blythe. The pictures are the same as in the magazine.

I was inspired to type it up after having gone to see a show of James Ravilious’s works at the Fry Gallery, running from 18th June – 24th July (2016). The exhibition’s booklet has a quote by Olive Cook from Matrix Magazine #18: "I know of no other presentation of a particular place and people which is as broad and as captivating as James Ravilious’s photographs of North Devon. They are the fruit of a quite exceptional acuity and patience of witness and of a quite unusual humility and warmth of spirit. This great body of work establishes its author as a master of the art of photography whilst at the same time it makes an unparalleled pictorial contribution to social history.“

James Ravilious – Young Bulls eating Thistles

Plainly Pastoral – James Ravilious. World of Interiors. March 1996.

For over 20 years photographer James Ravilious has captured on camera powerfully candid images of rural North Devon life for the Beaford Archive. A Corner of England, a new book of his pictures, is full of ‘private moments’ photographed without pathos.

This second collection of James Ravilious’s work has to be studied for three distinct reasons. Because it is in the great tradition of Henri Cartier-Bresson, because it corrects our distorted vision the English countryside, and because it reveals the poetry of the commonplace. In 1973 Ravilious was invited to restore and add to the Beaford Archive, a remarkable library of photographs of village life in North Devon. This wonderful book shows him way ahead of his commission. His Leica records his own intimacy with the region, its landscape, its people, its creatures. No ordinary journalist or social historian could have gained

Ravilious’s entree to these extraordinarily private rooms and fields, or be taught to see what he so naturally sees.

James Ravilious – ‘Dr Paul Bangay visiting a patient, Langtree, Devon 1981

The book’s pictures have been drawn from his own contribution to the Beaford Archive and he describes them as ‘rather like scenes from a tapestry I have been stitching over the years’. His wife Robin, a local girl, contributes a few hard facts. ‘The small mixed farm is the commonest unit still. Short of labour, short of capital, bothered by paperwork and recession, farmers struggle stoically in a cold soil, high rainfall and awkward upland terrain…’

James Ravilious – Pigs and woodpile, Parsonage Farm

Ravilious’s camera scrupulously avoids wringing the usual bitter-sweet agricultural drama out of this situation and his work is masterly in its absence of comment.He has a way of capturing a private moment without making it public, so to speak. So the reader/looker has to share his intimate views if they are to see anything at all. As one stares into these twisting lanes, farmyards, churchyards, bedrooms, kitchens, animals’ faces, sheds, shops, schools, one often feels apologetic at invading something so personal, then grateful for having been shown what is actual, true and good.

James Ravilious – Red Devon cow, Narracott, Hollocombe, Devon, England, 1981

This is a rural world without ‘characters’, only people. Not even the old tramp sunning himself amidst the rubbish tip of his belongings is a character – just a naked man on the earth. Nor do the farm animals set out to beguile but are captured without sentiment. A snowdrift of geese on a darkening hilltop and a dog on a blackening road are waiting for the first thunderclap. A sick ram rides home in a tin bath. Here is the ordinariness of the harsh and lovely pastoral. The Ravilious ‘interior’, whether of houses or hills, can shock or inspire- usually both. A rare country book. – Ronald Blythe.

James Ravilious –

Storm Clouds with Geese

– ‘A Corner of England: North Devon Landscapes and People’ by James Ravilious. Lutterworth Press.

The Churches in Cambridgeshire are some of the least documented in Britain. Cambridgeshire really gets thrown into a void and all the books about the region focus upon the City and the university or Ely; Sometimes the National Trust’s properties like Wicken Fen and Wimpole Hall will also get a mention but there is little else documented on them, outside of pamphlets or the impenetrable Pevsner.

These are the wooden hand carved and probably medieval pew ends of Swavesey Church in Cambridgeshire. Below is a photograph of fourteen of them in a line but there are around fifty carvings in the church itself.

Listed as ‘Suauesye’ in the Domesday Book, the name Swavesey means “landing place (or island) of a man named Swaef”, it was on the edge of the un-drained fens and so it would have been a marsh landscape of islands.

A castle was built here in the late 11th or early 12th century, though is believed to have been derelict by 1200. Swavesey served as a port and subsequent market town and was fortified at the end of the 12th century.It had a port area dug into the centre of the village too. With the draining of the fens the only evidence of this a network of ditches. The draining of the fens bought fields and arable wealth to the town.

The present parish church in Swavesey, dedicated to St Andrew since the 11th century, has a double aisle aspect to its nave. The east window in the Lady Chapel contains a 1967 Tree of Jesse by Francis Skeat.

In writing up an article on Brangwyn’s interior design for 13 Lansdowne Road, London, I discovered a little more about the house and it’s owner. Below is the history of the house and then under is the article from The Studio Magazine, in 1900.

Nos. 11 and 13 were a pair of no doubt half stucco villas very similar to the others on this block. However, both houses were acquired in the late 19th century by Sir Edmund Davis, the millionaire and patron of the arts who built Lansdowne House. In around 1900, shortly after his marriage, he united the two houses, with the help of William Flockhart, the architect of Lansdowne House. Around the same time their facades were remodelled in Gothic style. Several rooms in Davis’s double villa at Nos. 11 and 13 were decorated and furnished by Frank Brangwyn around 1900. Charles Conder also painted a number of panels in water-colour on silk. Much of Brangwyn’s work is said still to remain. †

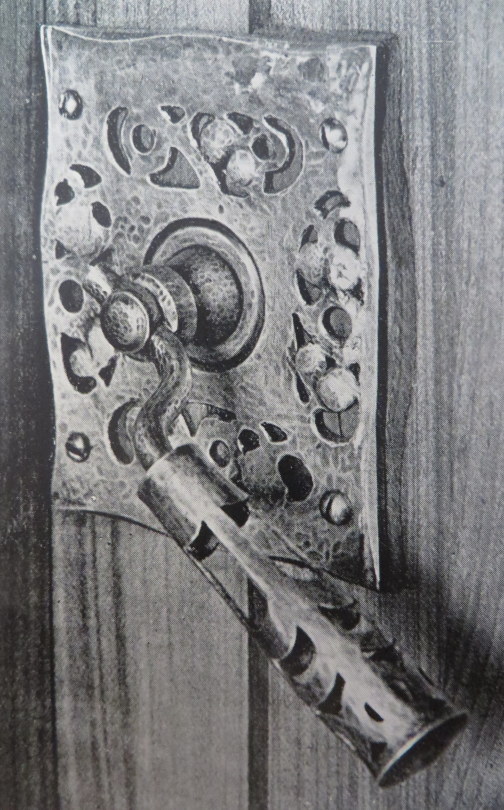

Frank Brangwyn designed door handle.

A bedroom decorated by Frank Brangwyn. From, The Studio: Volume 19. February-May 1900

Frank Brangwyn designed bedroom with freezes.

Although the collecting of pictures has ceased, of late years to be a general fashion, it certainly cannot be said that people with artistic tastes have lost

their desire for surroundings that are attractive and aesthetically satisfying. The lessened demand for pictorial productions does not mean that art in the broad sense has become uninteresting to the majority of thinking men, but simply that a conviction has grown up that other, and perhaps better, ways of adorning modern houses can be found than the old device of covering the walls with a heterogeneous collection of canvases of different dates and without any community of style.

What has happened is transference of patronage from the picture painter, to whom formerly it was given almost exclusively, to the decorator and design, whose right to place in the front rank of his profession is gaining daily a wider and more sincere recognition. This is to some extent a reversion to the creed of the Middle Ages when there was not the hard and fast line that has been drawn in modern times between workers in various branches of art.

The medieval artist took a very comprehensive view of his responsibilities, and spared no pains to equip himself so completely that he would be equal to whatever demands might be made upon him. He was by turns painter, architect, metal-worker, and sculptor, a craftsman full of adaptability, a practitioner learner in all the details of artistic production. But through all his practice ran the one dominating idea, that his mission was to decorate, to make something that would fulfil a specific purpose of adornment and

permanently beautify some chosen place. It is this idea that is being revived today. A steadily increasing section of the public is asking for something like consistency in the applications of art to modern life; and the wish to make practical aestheticism logical and complete is becoming a powerful factor in deciding the direction in which artists can hope to achieve success.

The specialist, the man who narrows himself down to fit a certain groove and refuses to see what lies beyond it, is losing his following because he does not realise that taste has changed and that his work does not satisfy art lovers whose ideas have progressed while his lave been standing still. His place is being taken by the more observant craftsmen who can read the signs of the times, and are prepared to adapt themselves

to what is plainly required.

Frank Brangwyn designed Light switches.

That the change is really in the best interests of art, though it may affect seriously a considerable class of artists, is quite undeniable. Decorating is the foundation of all that is best in artistic production, and its principles govern every detail of sound aestheticism. The great pictorial masterpieces which have set the standard of picture painting throughout many ages owe their authority to the fact that they were created by men who considered design as an absolute essential for the building up of great compositions, and depended on nature for the component parts of a pre-conceived pattern rather than for suggestions as to the subject that should be chosen for illustration.

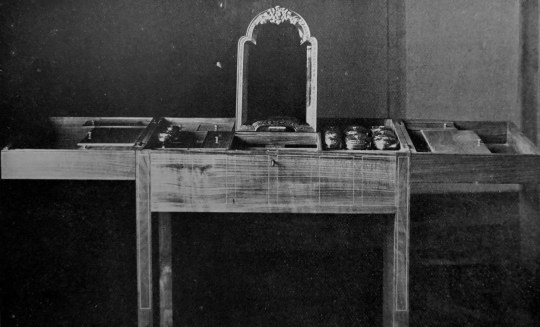

Frank Brangwyn designed Dressing table (open)

The modern painter has accustomed himself to worship realism, and to condemn as conventional everything which does not reproduce exactly the facts that nature presents. He has bowed down before the imitative accuracy and through of the old masters, but he has missed the value of the decorative convention which in their work brought nature and art into harmony; and he has lost in consequence the guidance by which his effort can most surely be saved from straying into vague irresponsibility. Therefore, a change in the public taste, and the growth of a demand which will oblige the workers to study more closely the laws of decoration, cannot fail to improve the character of their art, and give it eventually a higher value and significance.

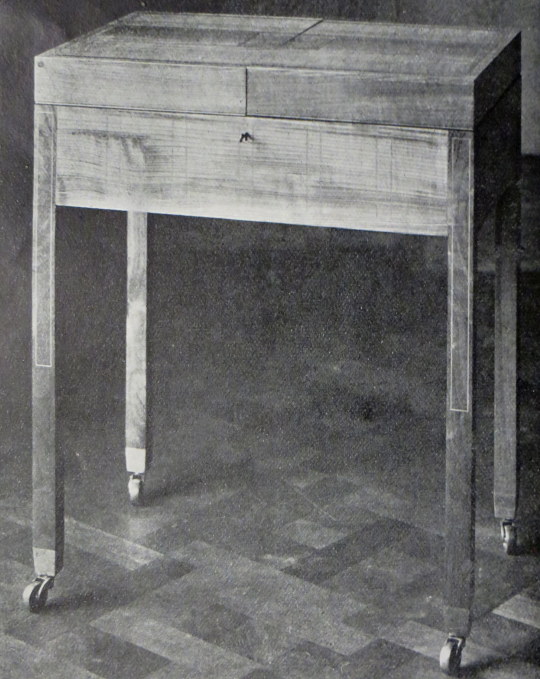

Frank Brangwyn designed Dressing table (closed)

At present the number of men who have set themselves to satisfy the new condition is distinctly limited. In the great array of working artists some are

too wedded to their habitual methods, or too well satisfied with the successes they have made in the past, to care to launch out in the fresh directions; others are too blind to what is doing on about them to see that they cannot hope to raise a fresh crop on the ground that their predecessors have already exhausted. Only here and there is there to be noted evidence of more correct appreciation, signs that the position of affairs is read aright, and that its necessities are properly and practically understood; but though these evidences are scattered they are plain enough to put beyond question the change into professional practice that is inevitably coming.

Frank Brangwyn designed freeze (detail)

No one, perhaps, deserves greater credit than Mr F. Brangwyn for keen and prompt appreciation of the duty that lies upon the artists of to-day. He is an instinctive decorator, with a true knowledge of all the refinements of design, the subtleties of colour arrangement, and the elegance of line, which must be closely studied by the craftsman who wishes to do work made a reputation that stands as high abroad as at home; and as a designer of strained glass, textiles, and woven fabrics, metal work, and other ornamental accessories, he has few rivals. One of the most interesting of his developments has been as a decorator of houses. Here he has been able to combine his many-sided knowledge of the applied arts with all that is most original in his pictorial feeling, and to unite harmoniously exquisite freshness of fancy with constructive ingenuity of a delightful kind. As a

consequence he has gained artistic effects that are in some respects unique, because they are the outcome of his peculiar individuality, and reflect his own personal beliefs about the part that aesthetics should play in modern life.

Frank Brangwyn designed freeze (detail)

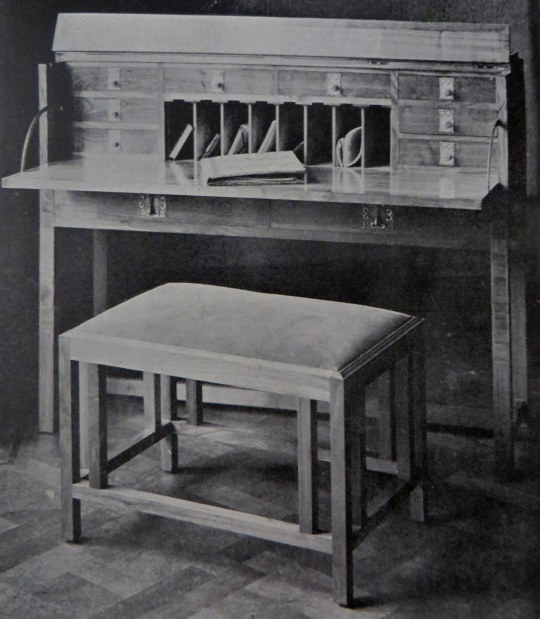

His most recent effort in domestic decoration has just been carried out for Mr. and Mrs. Davis at 13 Lansdowne Road, London, where, with other well-known artists, he has helped to give an ordinary London house an extremely attractive aspect. His share in the work is the principal bedroom, in which every detail of the arrangement, every piece of furniture, and every little accessory by which the decorative scheme is perfected, can be claimed as an expression of his artistic creed. The room illustrates in every part the feeling that dominates the whole of his practice in painting and design; and in its subdued, yet varied, harmony of colour, its severe dignity of line, and its atmosphere of absolute fitness for its specified purpose, it bares the stamp of an artist who does nothing without exact calculation, and leaves no detail to chance.

Frank Brangwyn designed Fireplace.

There is an especial charm in the manner in which the colour is managed. To gain response without dullness and delicacy, without monotony, is the first essential in the decoration of a bedroom, so Mr Brangwyn chose a

scheme of quiet tints that would combine into a restful effect of warm greys. Into the frieze of figures and landscape, and into the panels on the upright strips of woodwork which divide the walls into compartments, he has introduced tones of warm blue and fresh colour, and the cornice of the ceiling is in a deeper tone of the same blue.

Frank Brangwyn designed bed-head.

The doors, skirting, over-mantel, and all the articles of furniture are made of unpolished cherry-wood, the warm tint of which contrasts effectively, and yet not strongly, with the brown paper that is the covering of the walls; and the floor is oak parquet not too highly polished. A slightly more definite note of colour, a rosier pink than the flesh colour in the frieze, accentuates the panel that, above the head of the bed, hides a telephone by which the occupant of the room can communicate with other parts of the house. The door-handles, the switch-board for the electric light, and the little ring handles which are on the small cupboard doors of the over-mantel, are in oxidised silver, quaintly modelled and full of detail. Those lines of the furniture, like those of the room itself, are dignified and without any restlessness, severe perhaps in their simplicity, but neither heavy nor trivial.

Frank Brangwyn designed Desk and seat

Frank Brangwyn designed A handle from the desk

They have in form the same character that there is in the colour – a subtlety that prevents the minute care that has been exercised in perfecting them from becoming too obvious. Indeed, careful, studied, and exact, as

the whole work is, it has a curiosity happy air of spontaneity, and makes no display of labour or eccentric ingenuity. It I a decoration without a flaw, and it shows most hopefully what vitality there is now in the school of design that is making its influence felt amongst us.

† http://www.ladbrokeassociation.info/LansdowneRoad.htm#Nos1to27

I want to believe the internet is a nice utopia of thought and freedom for people, so this is really why I type up obscure interviews and articles on people for this blog. So far this has been limited to Paul Nash, Frans Masereel and Eric Ravilious but I have many others earmarked from niche publications that I own that seam far too expensive to buy. I hope they are of interest to you all and here is another on John Piper, at this time aged 60. It has a long introduction by Spender but I think it’s nice to read Piper expressing himself about his work, mid career.

A Talk with John Piper by Stephen Spender.

From Encounter #116. May 1963.

When I first knew John Piper, in the ‘thirties, he was one of several painters (Ben Nicholson was another) who resisted the turning of Coldstream, Moynihan, Pasmore, and the Euston Road painters towards portraits, landscapes and still lifes. These were artists who, a bit fastidiously, pushed representation towards a frontier where it began to turn into near-abstract drizzly lines (Coldstream), pure colour (Pasmore), rich lumpiness (Moynihan).

John Piper has a lean and hungry look and a lank cheek, like Caesar’s idea of Cassius, and was perhaps also a bit quixotic, as though he might suddenly appear in armour. Although he supported all the virtuous left-wing causes and conscientiously attended every director’s meeting of the Group Theatre, he went on painting abstracts about the size of windmills. During the war he became a War Artist, a position for which his love of architecture, ruins, and an atmosphere of drama admirably qualified him. His paintings of burning churches and barns form, with Moore’s shelter drawings, Sutherland’s iron foundries, the best part of the artistic record of the war.

Before the was, as though to prepare himself for events, Piper has started doing collages of Welsh villages and landscapes. He also did the set for the Group Theatre’s production of ‘Trial of a Judge’. After the war he established a new reputation as a topographical artist, with his series of water colours of Windsor Castle, Renishaw, and other famous houses. He continued with Welsh landscapes – pen-and-ink scratched,with texture like that of cracks in slate, slopes of shale, enclosed in golden washes.

He went on working in the theatre (doing the sets among others for Billy Budd) and painting abstracts. Recently he has done a whole series of oils and water colours of Venice and Rome. Piper is in fact an extremely prolific painter, branching out into many different styles and activities, but at the same time with a very marked consistency which makes a Piper, whether it is a water colour two inches by four, or a stained-glass window the size of a battleship, immediately recognisable. All the same, his work is (it seems to me) very uneven on account of the tension in his nature between the almost oriental richness of some of his water colours, and the extreme dryness which shows in many of his oils, even when they are theatrical and garish. His achievement is absolutely honourable: a fusion of a life-long search for a contemporary idiom with a passion for tradition. He is one of the few English artists whose reputation is more likely to increase than to decline.

To-day tape-recorders have had an effect on interviewing like that of photography on drawing. A printed interview appears a transcript a tape-recording, a bad imitation of one, or a fictitious intervention of the interviewer. Since I hate tapes, and anyway do not know how to use them, I will leave my notes (made in the course of a day spent at the delightful stone farmhouse in a sheltered valley near Henley, where the Pipers live) much as they were written.

Some of them are taken from conversation, some of them were written for me by John Piper before I arrived. It is John Piper speaking:

The Eye.

There isn’t a difference between “abstract” and “topographical” in the sense that one might consider “abstract” as purr invention, and “topographical” as imitation. The reason for this is that nothing comes out of a visual consciousness that has not already been received by the eye. All visual invention is the result of visual experience and observation. Everything is drawn out of the stock-pot of visual impressions. Abstraction is a way of inventing variations on the visual experiences one has had, but these may not prove enough to make a decent painter. There have been very few abstract masterpieces apart from those by Mondrian and Rothko. So when one looked into one’s heart and asked “Where do we go from here?” one looked at one’s own nature. I found I was English and Romantic, so I looked at Cotman, Turner, Blake, Palmer and painters in that in that tradition and tried to draw the things I seemed born to love.

Topography.

Topography is a branch of Romantic art, and it is also a branch of particularisation. For Romantic art consists in seeing the wing of a bird – a tower – a hop field – and interpreting all nature through the particular. Topography at its best is the interpretation of the world as a vision of the place. The best topographical paintings have spirit of the place in the time, not just the representation of the place, as Cotman expresses the atmosphere of places in Norfolk in the 19th century. Giorgione’s La Tempesta is the epitome of every virtue topographical art should have.

Photography.

Photography us useful because it makes one’s vision ridiculous. It proves that what one has seen is in literal fact a cliché. I never take photographs of anything I draw, unless I think the photographs may be useful as something to react against.

Abstraction.

Abstraction is much more difficult for English artists than some of them realise. By habit, certainly, and probably by temperament m most English people are literary before they are visual – they have to go through some process, some ritual almost, before they see at naturally and simple. Everything is wrapped in a known idea of itself, a concept. And then, when they do begin to see a thing directly, more or less for what it is, half the time they want to reinterpret the experience in words. Intensity! Intensity is all – but the intensity is made of something, experiences, love, hate, fears: and the natural progress for an Englishman is to explain himself in words before he sings or scribbles.

Crafts.

Nobody can possibly have more than two or three original ideas to bring to any craft, without renewing himself by working with his hands all by himself in the studio. The rest is tinkering, improving, tidying, untidying, and doing variations. People think that they can be original stage designers, and can go on being original indefinitely. All they’re doing is turning round on the same spot and facing different ways, using the same two or three little ideas they had when they were twenty: unless, of course, stage designing is simply another form of interior decorating, which it is often thought to be by the public and producers, and especially by music critics, who like everything beige and grey so not to interfere with the music. As for stained glass, there had not been any new ideas in that – not even little ones – for 200 years until Léger and Matisse came along (preceded by a herald or two like Miss Geddes and Miss Hone).

Stained Glass and Real Painting.

The bogey of stained glass is its recent history, like the bogey of English painting fifty years ago. You have to steer through all the crafty “traditions.” But in fact the proper rules of the craft (as opposed to the acquired traditions) help a lot by providing an artificial discipline, so that you don’t have to invent one of your own. That’s the horror of crafts. In other words, the limitations of the medium itself, the craft, make half the troublesome decisions for you before you start, and set the pace, and then the craftsman, if he is a good craftsman, takes the strain of a lot more decisions – tensions – all those that have to be made from minute to minute during the work. It is a rest, really, for the designer, except for the enormous area of a window he has to cover. First-class interpretive craftsmen like Patrick Reyntiens or like Charles Bravery, the scenic painters, take nearly all the strain anyway.

No, what is really difficult is to create a masterpiece on paper or canvas all by yourself in the studio with no artificial discipline of the craft that can offer ingenious solutions, no outside help at all. That’s what’s difficult. Loves, hates, fears: those are what painting is about. It is very difficult to paint love and hate without bringing in the things they are about. Abstraction can be achieved, and complete abstraction, without total loss of richness and intensity. I do belie that. Only, as I say, it is much more difficult than most people make out. People pretend that they’re born into it these days. They aren’t, any more than Mondrian was. He achieved it though a long, lonely sweat, like anyone else.

Twenty-five years ago I painted purely abstract paintings for five years, mixed with some collages (which we weren’t allowed to call collages by the galleries, because they said the name suggested that they might come unstuck). – which were done, more or less, from nature. I did actually go out with a big sketch book full of scraps of grey and brown-coloured paper, and a pair of scissors and a bottle of gum or glue. I tried to keep these going side by side with the oils, which were purely abstract-schematic arrangements of shapes and colours I wanted, even then, some of the natural energy and fecundity of nature to get into them, even at second hand. It got into Mondrian through his early works, and through his post-cubist pictures. All this time I had a feeling that-while one was learning a great deal (by putting one colour in a positive shape against others) about the mutual reactions of positive colours and positive shapes, which is the right stuff – at the same time one felt that the things one was producing lacked the richness, the fullness, and the ripeness of life: which, of course, they did, because one wasn’t rich, full or ripe enough; and still one isn’t but you can’t go on waiting till you die.

Michael (Gordon) Brockway – Manor House, Downton.

This weekend I bought a painting by Michael Brockway. It’s a landscape with a house. I like to know what paintings are off, so I turned detective.

The first step was removing the picture from it’s frame. On the back was ‘Manor House, Downton’. A google of that came up with hundreds of images of the Television show ‘Downton Abbey’. I then Googled ‘villages called Downton, UK’ and a list of ‘things called Downton’ from Wikipedia came up.

Using the church and it’s spires in my picture, I went down the list of villages. The matching church was Downton Wiltshire.

Then after entering ‘Manor House, Downton, Wiltshire’ I looked on Google Maps, the picture below is of the house and the church. The roof-line matched.

In the other details on the village I was lucky enough to get an estate agent’s property listing, with the house in my painting.

“It is a building with history. Below is a quote from the Daily Mail on the property when it went up for sale: First lived in more than two centuries before William the Conqueror set foot on British soil, this ancient house is believed to be the longest continually inhabited home in the south of England.

Dating back to 850, the Manor House in the pretty Wiltshire village of Downton, was once home to Sir Walter Raleigh.” “The Grade I-listed five-bedroom, four-bathroom house was originally founded as a chapel in 850, after which it was transformed into a medieval hall house, and subsequently into a comfortable country home”.

“In the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth I leased the house from Winchester College, giving it first to Thomas Wilkes, Clerk to the Privy Council, and then to her favourite, Raleigh. In 1586 he invited the monarch to stay, but not before he made substantial improvements to the property, and the Raleigh family coat of arms still stands above the fireplace in the house’s wooden panelled Great Parlour. Another improvement by the Raleigh family, who lived at the house for about a century, was the addition of a first floor, created with wood from a ship which had been sailed up the River Avon and then dismantled”.

On Michael Brockway more detective work was needed. He was Born in 1919, in London. Michael Gordon Brockway was a painter and author. He was schooled at Stowe and Peterhouse, Cambridge. After WWII he studied under Simon Bussy in France. After deciding to take up painting professionally he studied at the Ruskin School of Drawing, Oxford and Famham School of Art.

In addition to his exhibits at London’s Royal Academy, he has been the subject of several successful solo exhibitions at Walker Galleries, King Street Galleries.

In 1952 he wrote a monograph on the watercolourist Charles Knight, R.O.W., R.O.I. The book was a limited edition of 350 copies.

He is a honorary life member of the New English Art Club (NEAC), other members were: Walter Sickert, William Orpen, Augustus John, Gwen John, William Rothenstein, Evelyn Dunbar and Muirhead Bone.

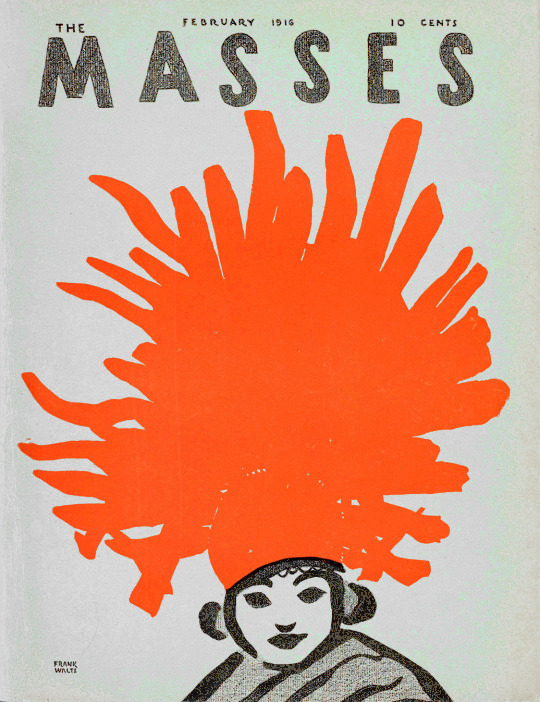

In a garage sale I bought a book of magazines. I love old newspapers and annuals bound into books, it saves them from damage and keeps them in order of date. On that day, I came away with a bound book of The Masses Magazine – A left wing american publication from 1911-1917. It was an interesting period for America, with the Mexican revolution and the start of the First World War happening around them.

“Perhaps the most vibrant and innovative magazine of its day, The Masses was founded in 1911 as an illustrated socialist monthly, and it was soon sponsoring a heady blend of radical politics and modernist aesthetics that earned it the popular sobriquet “the most dangerous magazine in America.”

The magazine had three editors during its first two years—Thomas Seltzer, Horatio Winslow, and Piet Vlag (the magazine’s founder)—but for the remainder of its short life The Masses was brilliantly edited by Max Eastman, who—with Floyd Dell, as managing editor—helped turn it into the flagship journal of Greenwich Village, the burgeoning bohemian art community in New York”. †

After Max Eastman took over editing the magazine, the front covers became more colourful and less conservative looking. Inside the magazine the lithographs and illustrations became more contemporary, looser drawings rather than cartoonish ‘Punch’ like illustrations.

In his first editorial, Eastman argued: “This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers.”

The Masses magazine cover, by Frank Walts, 1916.

Many scholars have noted the high quality of the writing, imagery and design of the Masses. Specifically, they all identify the magazine’s visuals as its hallmark. The complete list of works that mention the magazine would be too extensive to list exhaustively, but in a number of works, the Masses takes centre stage. Discussions on the magazine and imagery can be found within histories of print journalism and the little magazine; works on the intellectual and artistic life of New York City in this period. ‡

Max Eastman was accused later on of going against the collective nature of the magazine when he wrote and published articles and illustrations without consulting the board who hired him. Eastman hired an assistant editor, Floyd Dell, he recalled “some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures”.

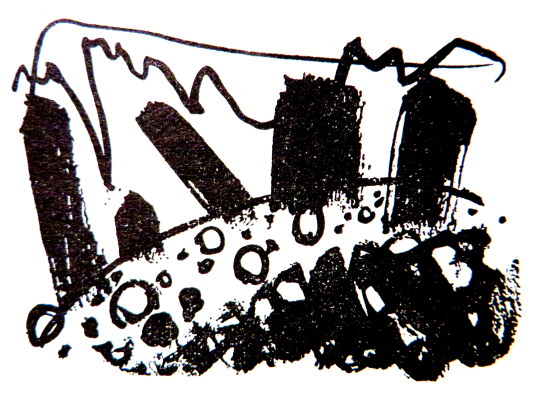

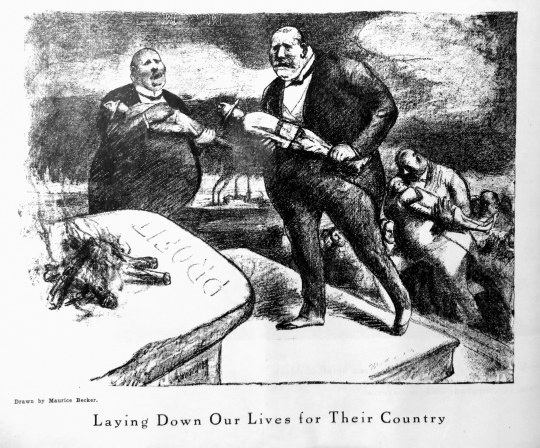

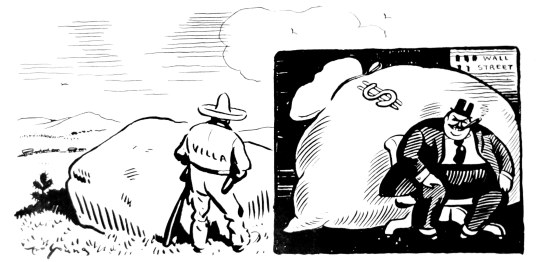

Maurice Becker – Laying Down Our Lives for Their Country

Above is a typical illustration from the magazine; Capitalists laying down the bodies of soldiers at the alter of Profit. The magazines socialist agenda wasn’t masked at all. Below a picture about the Mexican Revolution and how a Mexican is hiding behind a rock from gunfire where as the American Fat Cat is hiding behind the gold of Wall Street.

Maurice Becker again, – This was one of the more interesting illustrations, it was untitled – drawn direct onto newspaper print and then printed up. Maybe unknowingly initiative.

Maurice Becker – Christmas Cheer, 1914.

The picture above is captioned “Cheer up, Bill – time next Christmas comes around, we may be prisoners of war.”

In 1918 Maurice Becker became a conscientious objector to American participation in World War I. He fled to Mexico with his wife to avoid the draft. He was arrested upon his return to the United States in 1919 and was tried, convicted, and sentenced to 25 years of hard labour, of which he served 4 months at Fort Leavenworth prior to commutation of his sentence. After he was released he lived in Mexico for a few years before returning to America.

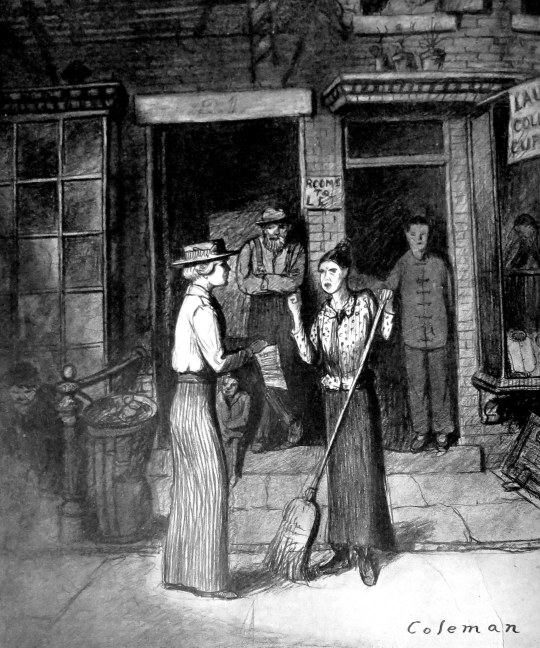

Glenn O. Coleman – Overheard on Hester Street.

(To the Suffrage Canvasser) “You’ll have to ask the head of the house – I only do the work.”

The Masses, as in the picture above, were keen to promote women’s rights.

The magazine vigorously argued for birth control (supporting activists like Margaret Sanger) and women’s suffrage. Several of its Greenwich Village contributors, like Reed and Dell, practised free love in their spare time and promoted it (sometimes in veiled terms) in their pieces. Support for these social reforms was sometimes controversial within Marxist circles at the time; some argued that they were distractions from a more proper political goal, class revolution.

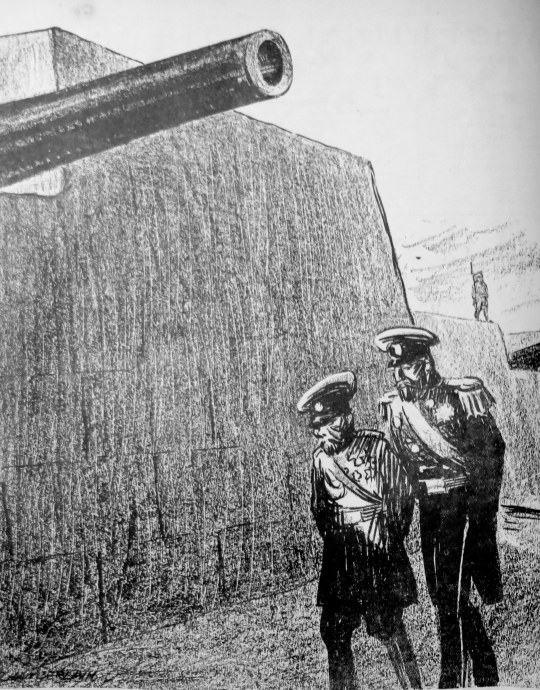

K. R. Cahmberlain – At Petrograd

Russian Officer: ‘Why these fortifications, your Majesty? Surely the Germans will not get this far!” The Czar: “But when our own army returns…?”

It’s hard to say if the Masses did anything at the time to change the political thinking of America. It’s true to say they sponsored and promoted art and writers that would go on to become significant. As a historical document, it’s value has been justified by time.

The Masses found itself constantly entangled in lawsuits claiming libel brought by major corporation and syndicates (most notably the Associated Press), and eventually the government, invoking the Espionage Act of 1917, barred it from the mails in August 1917 for its critique of the U.S.’s involvement in World War One. Without being able to ship the magazine to it’s subscribers the magazine folded.

† http://modjourn.org/render.php?view=mjp_object&id=MassesCollection

‡ Constructive images: Gender in the political cartoons of the “Masses” (1911–1917)

Following my Post on the John Nash ‘Harvesting’ Schools Print I thought I would present another unravelling of prints from my collection of books.

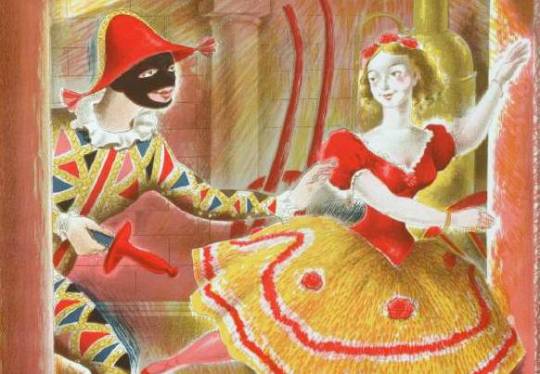

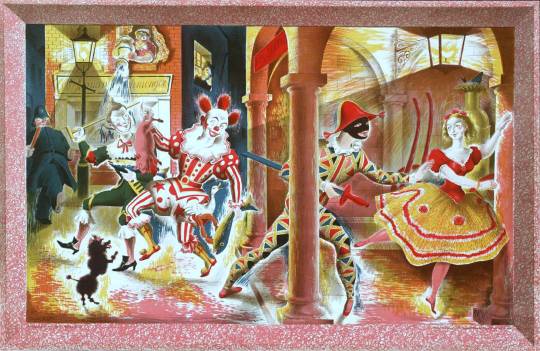

A detail of Harlequinade by Clarke Hutton, 1946.

Stanley Clarke Hutton was born in Stoke Newington, London, on 14 November 1898, son of Harold Clarke Hutton, a solicitor, and his wife Ethel, née Clark. In 1916 he became assistant stage designer at the Empire Theatre. About a decade later he took a trip to Italy, which inspired him to become a fine artist.

In 1927 he joined A.S. Hartrick’s lithography class at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, after Hartrick retired he taught the class himself until 1968. He experimented with the technique of auto-lithography with the aim of developing a way of printing affordable full-colour children’s books, and worked with Noel Carrington at Penguin Books to develop the Picture Puffin imprint. With Penguin he also illustrated Popular English Art by Noel Carrington, for King Penguin Books, in 1945.

He used the auto-lithography techniques he developed for the Oxford University Press’ Picture History series. Other notable publications where for The Folio Society. He illustrated about 50 books in all, for publishers in the UK and USA.

His paintings, figures and landscapes, were widely exhibited. His later work took on a surrealist influence. He died in Westminster in the second quarter of 1984.

A Picture History of India by John Hampden – Oxford University Press, 1965

Illustrated by Clarke Hutton

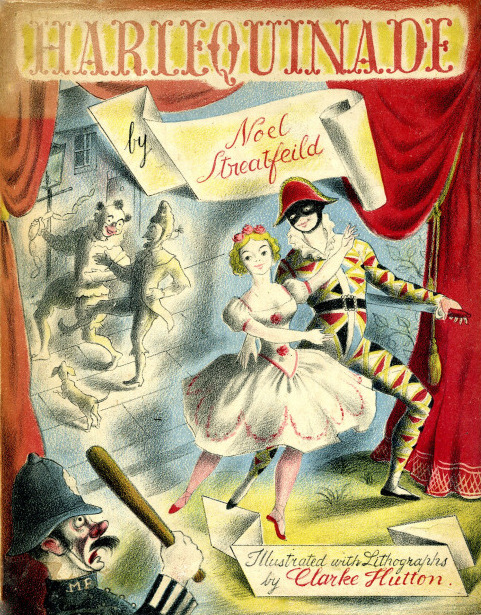

It was his illustrations for Noel Streatfeild’s ‘Harlequinade’ that the link to the Schools Print lays. It’s remarkably similar. Most of the figures are all represented, the harlequin, the ballet dancer and the policeman in the corner. Again under the same street light the clown, dog and jester appear.

The book was published in 1943 and the Schools Print was produced in 1946. So rather like the case of the John Nash ‘Harvesting’ the Schools print is made from recycled earlier sketches and ideas, in my opinion, to great effect – these days it would be considered good marketing for the book.

Noel Streatfield – Harlequinade. Chatto and Windus, 1943.

Illustrated by Clarke Hutton

Clarke Hutton – Harlequinade – A Schools Print, 1946.

About The Schools Prints:

Set up in 1945 by Brenda Rawnsley, the School Prints scheme commissioned well-known artists to create lithographs, which would then be printed in large numbers and sold cheaply to schools for display in classrooms. The aim was to give ‘school children an understanding of contemporary art’. Each lithograph had a drawn frame so that the print could be pinned to the wall.

In the spirit of post-war optimism, artists responded enthusiastically. The scheme was a unique attempt at giving children access to original works of art in a period of austerity but ended in 1949 because of financial problems.

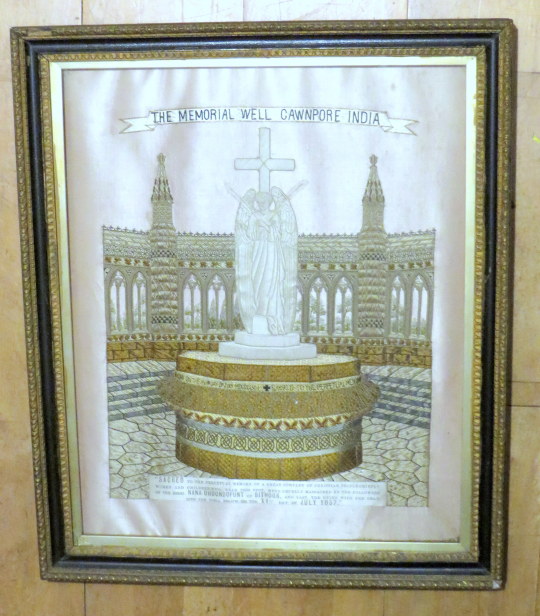

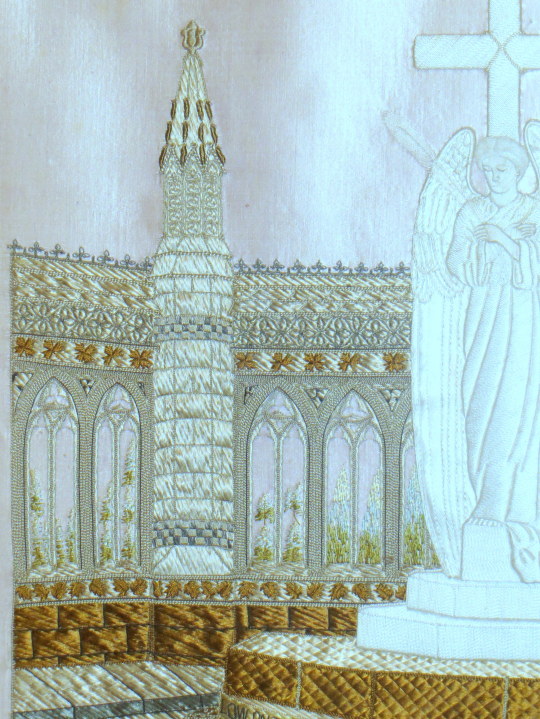

I was in an antique shop in Cambridge just before Christmas when I saw an embroidery on the wall. It was a Victorian memorial piece made from silk and the detail of it was stunning. It was done in the memory of the victims of Cawnpore. Below, in short, is the story of the Indian mutiny.

The large embroidery for the victims of Cawnpore.

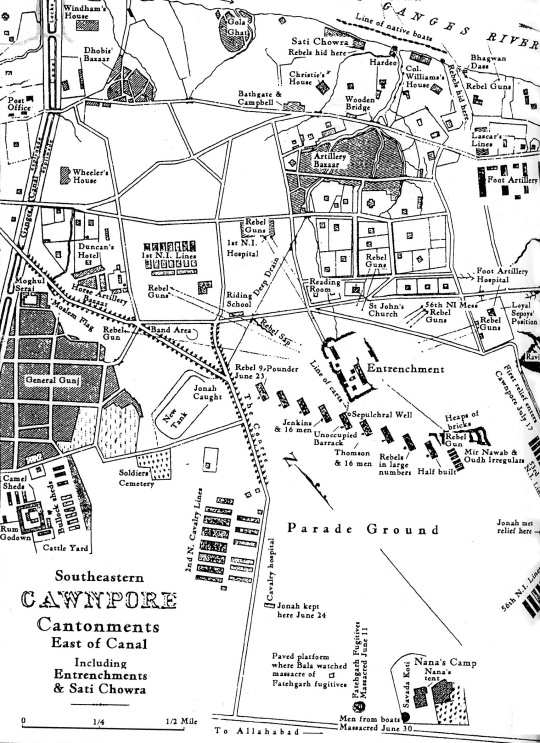

Cawnpore was a major crossing point of the Ganges and Grand Trunk Canal, and an important junction where the Grand Trunk Road and the road from Jhansi to Lucknow crossed. Cawnpore was to become a vitally important garrison town for the British, straddling key communication lines.

In 1857 it was garrisoned by four regiments of native infantry and a European battery of artillery and was commanded by General Sir Hugh Wheeler. Wheeler had served in India most of his life, had an Indian wife and a gross overconfidence in the loyalty of the sepoys under his command.

Sepoys were the native, Indian soldiers who served in the army of the British East India Company. On June 27th, 1857, in Cawnpore, India, a British garrison with many women and children, under siege, were offered safe passage and sanctuary. Instead, they were betrayed and butchered. The surviving women and children were later hacked to death. The British retribution, when it came, was unrelentingly severe.

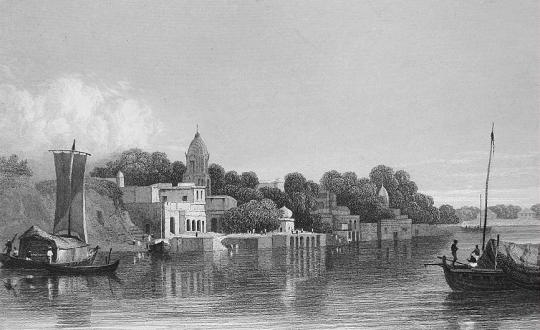

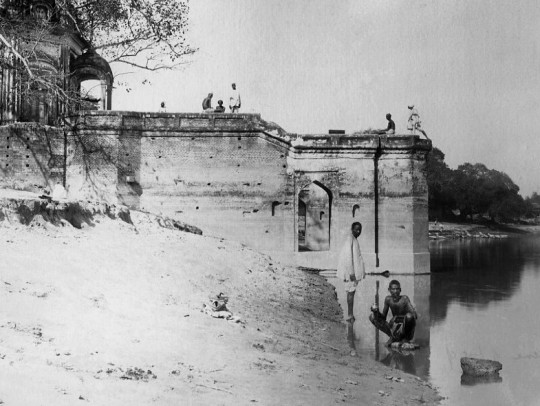

A View of Cawnpore, India, 1858) †

There was one complicating factor in the area that would come back to haunt Wheeler and the garrison. Nana Sahib was the adopted heir of the last great Mahratta king Baji Rao.

Unfortunately for Nana Sahib, the East India Company decided that Baji Rao’s pension and honours would die with him and would not be passed on to any successors. Nana Sahib lobbied hard sending an envoy, Azimullah Khan, to London to petition the Queen directly but to no avail.

This dispossessed Hindu aristocrat would play a dangerous double game before deciding who to support in the mutiny.

A Portrait of Nana Sahib, one of Victorian Britain’s most famous villains. – The Illustrated Times, 1857.

With the patronage of the Mughal Empire in New Deli the mutineers ransacked towns and cities. The Mughal Empire was to be reestablished of Hindus and Muslims, these combined forces where to evict the Christians from India forever. This turned a localised army mutiny into a more significant political challenge to the rule of the East India Company.

The slow response by the commander of the East India Company General Anson did not help. He underestimated the size and escalation of the challenge to the company’s authority. He would not be the only one to make that mistake in 1857

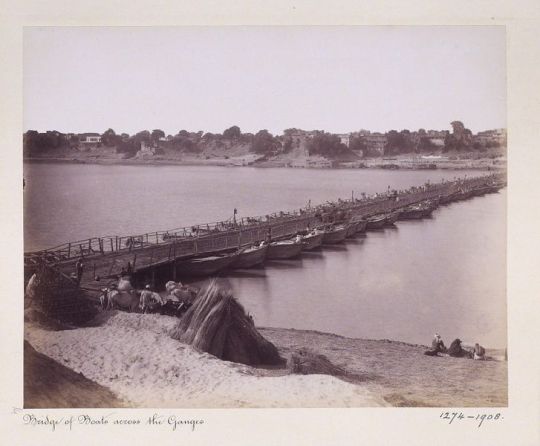

Bridge of boats across the Ganges at Cawnpore – Seeta Ram, 1814/15 – British Library

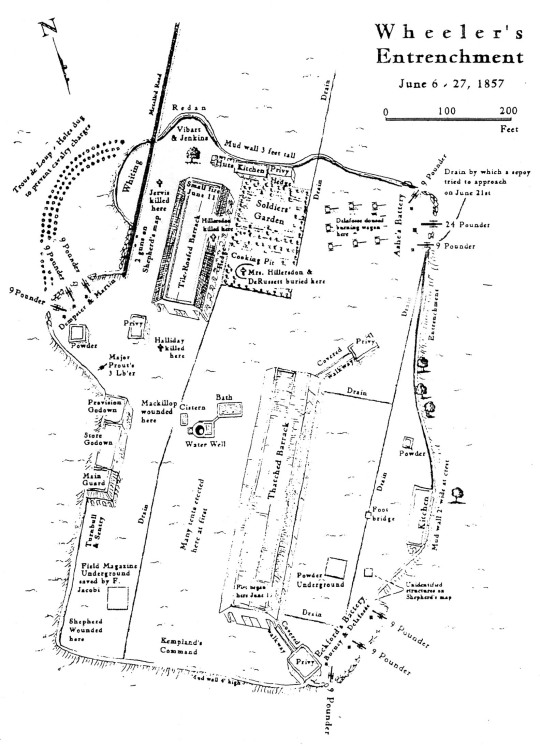

Wheeler expected reinforcements to come from the South of Cawnpore, so he made camp of defence a few miles South of the city at a small military base where barracks were being constructed. His hope was to build an entrenchment around this camp as a defence from the outside. However it was the height of the Indian hot season and digging defences was hampered by an iron backed ground. It was almost impossible to get the trenches below waist height and the surrounding area outside of the fortifications had buildings to shelter the enemy and their gunfire.

The biggest problem was the lack of decent sanitatary facilities. There was only one water well and that would be exposed to enemy fire.

The entrenchment would be fine to defend with a significant force of soldiers or for a very short period of time. As it was, there would be a thousand plus civilians with a pitifully small garrison of European soldiers who would end up having to defend for far longer than they had possibly anticipated.

Although no direct threat had yet occurred in Cawnpore, European families began to drift into the entrenchment and tried to find a space in one of the sturdier buildings available. The very sight of the Europeans withdrawing into relative safety was not unnoticed by the Indian sepoys and sowars.

To try and disperse the number of Indian soldiers away from Cawnpore, General Wheeler decided to send troops on various ‘missions’ to relieve garrisons in the region. They mutinied against the British, killing both their commanders. Oblivious to this the men making Entrenchment fortifications at the south of Cawnpore kept working.

Nana Sahib had declared his loyalty to the British and sent what volunteers he could spare to be at the disposal of Wheeler and for the defence of Cawnpore. He sent his units to camp just south of the Entrenchment, to guard the treasury. Wheeler had barely 250 forces in total and he had to defend a thousand odd civilians.

A Map of Cawnpore. The Entrenchment being centre-right.

Tensions would be raised on the night of June 2nd when a drunk Lieutenant Cox fired on his own guard. He missed, was disarmed and thrown into jail for the night. The following day the sowars were less than impressed when a hastily convened court failed to convict him of firing on his own troops. This seemed to confirm that there was one rule for the English and another for the Indians.

Rumours of mutiny and impending treachery were becoming so widespread that it was difficult to tell the truth from the rumours. There were still Native regiments based in the city. (The 1st, 53rd and 56th Native Infantry and the 2nd Bengal Cavalry).

It was to be the 2nd Bengal Cavalry that were the prime instigators of the mutiny. It seemed to them as if the English were already prepared for them to mutiny. They cited the insulting fortification of the entrenchment, artillery guns being primed and aimed at them, the fact that they had to collect their pay out of uniform and one by one so as to not all turn up in the entrenchment armed and en masse, the acquittal of Lt Cox and rumours that they were to be summonsed to a parade where they were to be blown to pieces all convinced the sowars that something was seriously amiss.

A map of Wheeler’s Entrenchment.

In the city at 1:30am on June 5th, three pistol shots signalled the start of the mutiny. At least one Rissaldar-Major Bhowani Singh refused to join his comrades and was cut down there and then.

As predicted by Wheeler the sowars began to burn buildings, loot and cause mayhem. The 53rd and 56th were groggily awoken by the panic and started to form up. The 56th began to panic and started to run off. European artillery opened up on the fleeing sepoys assuming they were mutineers too. If they hadn’t been before, they were now. Worse than that, the 53rd, Wheelers old regiment, were caught up in the cross fire. The confusion and panic had led the British defenders to fire upon what was probably the most loyal unit in the area. Soon virtually the entire native contingent had risen up or run off.

It was then that Nana Sahib’s and his men looted the treasury and set off down the Grand Trunk Road. He caught up with the bulk of the mutineers at Kalyanpur. Seeing advantage for himself, he therefore pleaded with the mutineers to about-turn and come back with him to besiege and capture the city on behalf of the Mughal Emperor, bribing the men with the British Gold.

Ominously for the British, the mutineers trundled back into town. This time, they made sure that they had expunged all the Europeans from outside of the entrenchment and systematically plundered and destroyed all European owned property. Native Christians were also singled out for gruesome fates.

Whilst all this was happening Nana Sahib took the time to write a letter to General Wheeler informing him to expect an attack the next morning at 10am!

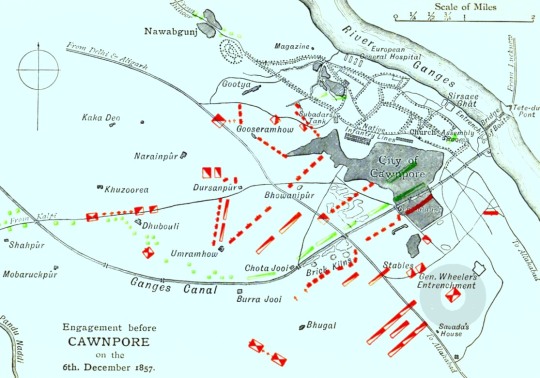

A larger map of Cawnpore showing the Entrenchment bottom left and the Grand Trunk Road slashing top left to bottom right.

The attack started half an hour late at 10:30 on June 6th. It would actually take the form of a prolonged artillery bombardment but this offered little comfort to the defenders who realised quickly that the mutineers had more and better guns available to them and that the entrenchment offered and that they were surrounded.

Fortunately for the British, the mutineers were reluctant to test the defences in an all out assault. In fact, they had been led to believe (falsely) that the entrenchment had gunpowder filled trenches.

The following days, and indeed weeks, would only confirm what a difficult position this was to defend. The fact that it was the hottest time of the year only added to the miseries of the defenders. The one well was exposed to the enemy artillerymen and snipers who took delight in aiming at the desperately thirsty defenders. Water extraction would have to take place at night to stand any chance of success. A second dried-up well would have to serve as the make-shift burial chamber. The solid ground was too difficult to dig individual graves. Dead bodies would have to be piled up outside the buildings awaiting nightfall when they would be dragged and dumped with as much ceremony as could be summonsed given the circumstances.

The defenders were becoming increasingly desperate, their already small quantity of soldiers was being steadily whittled down by the combined attritional effects of successive bombardments, snipers, assaults, disease and poor to non-existent medical supplies. Food and water were dangerously low and the hot season was still beating down the sun unmercifully on the defenders. By the 21st of June, they had probably lost a third of their number.

With the prospect of relief seemingly as far away as ever, General Wheeler assented to Jonah Shepherd slipping out of the entrenchment in disguise to ascertain the condition of the mutineer army. Jonah was picked up pretty quickly by the mutineers although they failed to appreciate that he had been part of the defending force and merely imprisoned him as a wastrel.

Whilst this was all taking place, Nana Sahib and his advisers had come up with a plan of their own to end the deadlock. They used a female European prisoner, Rose Greenway, to approach the entrenchment with the idea of initiating negotiations. She conveyed to the defenders a note that said that Nana Sahib was willing to offer safe passage to Allahabad for all those who lay down their arms. This offer was rejected by General Wheeler ostensibly because it hadn’t been signed and that therefore no personal guarantee had been offered.

The following day, June 25th, a second note was brought, this time by a different female prisoner, a Mrs Jacobi. This letter was signed by Nana Sahib himself. Debate swirled amongst the survivors and it was clear that there were two camps forming: Those determined to hold out versus those wishing to lay their trust in Nana Sahib’s assurance. Wheeler, already in a poor state of mind, was actually in favour of holding out, but when some of his officers began to talk of the sense in escorting the surviving women and children to safety, the old general relented and offered to lay down his arms in return for safe passage.

The next 24 hours saw an immediate improvement in the condition of the defenders. No longer having to brave the bombardment just to get a bucket of water meant that the defenders could drink their fill and wash and bathe for the first time in three weeks. Additionally, as the remaining rations would no longer be required for a long siege, allowances were doubled and the defenders could eat satisfying quantities for the first time in a long time.

With a day for preparation and laying to rest any remaining fallen comrades, the morning of the 27th June was designated as the day to board the boats to take them down the Ganges to Allahabad.

The ‘Sati Chaura Ghat’ on the bank of the River Ganges.

A large column was formed with General Wheeler leading from the front. They tried to show as much dignity as they could muster but the privations and conditions were unable to be concealed from the Indian onlookers. The respect shown to the front of the column gradually broke down as looters and pilferers tried their luck in grabbing the personal effects of those further down the column. More locals swarmed into the entrenchment hoping to find things of value left behind by the defenders.

One unanticipated problem was that the river was unusually dry and the boats were left fairly high and dry. It would take some serious dragging and effort to find the deeper parts of the Ganges. General Wheeler and his party, being the first to arrive, were the first aboard and the first to manage to set their boat adrift. It was at this point that some of the mutineers began to look nervously at the general’s boat floating downstream. It was clear that not all the boats were yet loaded and there were still a lot of Europeans waiting to board the at all.

There was a bit of confusion as the Indian boatmen jumped overboard and made for the banks. They knocked over the cooking fires on the boats before jumping in, thus setting some of the boats ablaze. Then, all hell broke loose. Tatya Tope ordered the 2nd Bengal Cavalry unit and some artillery pieces to open fire on the hapless Europeans. The massacre was merciless. Bullets flew from all directions as the Europeans desperately attempted to scramble into the burning boats.

Women and children were inevitably caught up in the deadly fire. At the boarding point, the carnage continued. It then stopped almost as suddenly as it started when the mutineers suddenly ceased fire. Any remaining women and children were taken prisoner and escorted to Savada House. Any remaining men were cut down where they stood. Approximately 120 women and children were thus taken away.

Wheeler’s boat, floating away was pursued. Under-fire and with the low tide, the sandbanks and rocks hampered escape efforts. General Wheeler’s own family members were probably killed in the water trying to free the boat.

Lieutenant Thomson led a last gasp desperate charge out of the river into the mutineers. Unbelievably, the suicidal charge worked and in fact allowed them to capture some vital ammunition. The next morning yet another grounding resulted in another charge by Thomson and 11 volunteers. Having left the boat the mutineers captured it and the people on-board were unceremoniously escorted off the boat. The men where executed on the bank and the women and children were taken back to Savada house. The men in Thomsons charge ran, hid, attacked and were surrounded. They ran to the river, four survived including Thomson – they swam to the centre of the river. They drifted downstream as best they could – although they now had to worry about crocodiles too. They came exhaustively ashore a few hours later. Their fortunes finally turned for the better when they were discovered by Rajput matchlockmen who worked for the Raja Dirigibijah Singh who had remained loyal to the British. They were taken, or rather carried, to the Raja’s palace. With the exception of Jonah Shepherd, these were the only male survivors of the ordeal.

A photograph of the river in 1908 showing the width at a fuller tide.

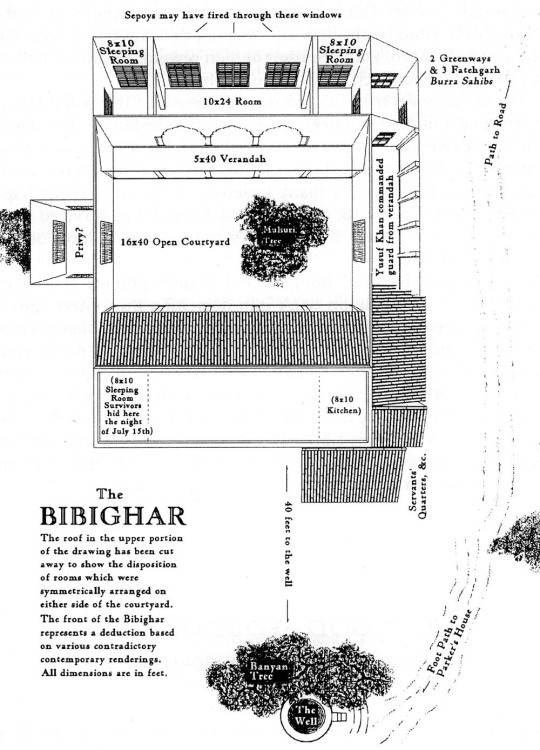

The dazed, shocked and confused women and children were moved from Savada House to the Bibighar. It was terribly cramped for the women and children. The original 120 women and children would later be joined by other women and children from Wheeler’s boat, some from a second flotilla from escaping violence in Fatehgarh. In total there were about 200 souls crammed into the house.

Nana Sahib placed the care for these survivors under one of his mistresses serving girls who would become known as the Begum. Her real name was Hussaini Khanum. She seemed particularly unmoved by the plight of her captives and did little to help them. Food was provided but little thought was given to the dignity or care of the prisoners.

Nana Sahib had decided to use these prisoners as bargaining chips to try and keep back the relieving force of Havelock and Neill. They demanded that the British retreat to Allahabad. Havelock’s force though advanced relentlessly towards Cawnpore. An army was sent by Nana Sahib to intercept the relatively small but determined flying column. They met at Fatehpur on July 12th where Havelock’s forces quickly out-manoeuvred the larger mutineer force and captured the town.

As it became clear that the British were going to enter Cawnpore, Nana Sahib, Tatya Tope and Azimullah Khan debated about what to do with their captives. As mutineers scurried out of the city, it was not clear how 200 women and children could be escorted anywhere and their use as bargaining chips had patently failed. Azimullah Khan was also worried that Nana Sahib might flee and abandon the mutiny altogether. The order was given to eliminate their prisoners.

At first the guarding Sepoys refused to obey the order. They had executed the remaining men without much thought, but murdering women and children was another matter. It was only when Tatya Tope threatened to have the sepoys themselves executed for dereliction of duty that they agree to try and remove the women and children from the courtyard for their execution.

The women had already realised what was going on with the execution of the remaining menfolk. They barricaded themselves in as best they could by tying the door handles with clothing. Some twenty soldiers opened fire into the cramped compound. A second squad that was to fire the second volley was so disturbed by what they saw that they discharged their shots into the air and staggered away. The sepoys now adamantly refused to finish the job off.

The Begum was so irate at what she called the cowardice of the sepoys that she had to get recruit her lover Sarvur Khan to finish the job off. He went into town and hired butchers with cleavers to finish off the nasty business. They were hacked to death. The following day, orders were given by Nana Sahib to clean up the scene of the massacre. They were surprised to come across the half dozen or so women and children who were still alive. The women actually threw themselves down the well rather than be murdered on the spot. The children, who were only five and six years of age, tried to evade the scavengers and mutineers until exhausted. They were then chased around the corner into waiting executioners who decapitated them. Eventually, all the bodies were looted of whatever pitiful possessions that they still had on their bodies and were then dragged to the nearby well and thrown down it.

The horror was indescribable. There was so much blood that they could not clean the walls and floors despite their attempts at scrubbing.

On the 16th of July, a group of British officers and soldiers were directed by fearful local Indians to the Bibighar. They were horrified by the smell and sight that greeted them. They had assumed that they were arriving to rescue the women and children. Any feelings of elation at the victories and relief quickly turned to feelings of despair and then through to vengeance.

A plan of the Bibighar, where the slaughter took place.

It was beyond comprehension for Victorian soldiers to believe that innocent women and children could be butchered in such a manner. Most pitiful were the tiny hand and footprints of the children who had been slaughtered.

A photo of the well from 1858.

Discipline had all but collapsed amongst the British who were in utter despair at the massacre. The slaughterhouse Bibighar became a place of pilgrimage for the British soldiers who then turned their indignation on any local Indians who happened to be in the way. They wondered how any of the locals could have let this massacre occur and do nothing to intervene and stop it. Neutrals became hostiles in the minds of the British soldiers. Looting, burning of houses and murder became acceptable as old testament-style vengeance was meted out indiscriminately. Looted alcohol fuelled the despair and destruction.

The worst vengeance was applied to any mutineer captured. No mercy was shown to them at all. A set of nooses was set up next to the well at the Bibighar, so that they could die within sight of the massacre. Colonel Neill decided that the crime was so serious, that all captured mutineers would be expected to clean up the scene of the massacre literally with their tongues. They were beaten and clubbed into licking the floor of the Bibighar compound. They would then be forced to eat Beef if Hindu or Pork if Muslim and then hanged at the gallows adjacent. Sweepers were employed to execute high-caste Brahmins. Some Muslims were sown into pig skins before being hung. The idea was to ritually humiliate and defile the victims to preclude any reward they might have expected to find in the afterlife.

The memorial at Cawnpore, 1860

Memorial at Cawnpore (present-day Kanpur), devised by Charlotte, Countess Canning (1817-61) and her sister Marchioness of Waterford (1818-91), with the figure of an angel executed by Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-67) and a screen by Colonel Sir Henry Yule (1820-89). C. B. Thornhill, Commissioner of Allahabad and superintending architect.

Count and Countess Canning paid for the sculpture, the large park surrounding it was paid for by a levy on the citizens of Cawnpore, as a sort of punishment.

Regardless of the savage history of the tapestry, I requested it as a Christmas gift. My mother and the antique dealer then both acted in a masquerade of it being sold until I was delighted on Christmas day with it. The detail of it is amazing. The work of the windows and brickwork, not to say the angel. All hand stitched.

† The History of the Indian Mutiny Giving a Detailed Account of the Sepoy Insurrection in India and a Concise History of the Great Military Events Which Have Tended to Consolidate British Empire in Hindostan – The London Printing and Publishing Company, London, 1858

The Body of text for this post and the maps were sourced from this website:

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armycampaigns/indiancampaigns/mutiny/cawnpore.htm