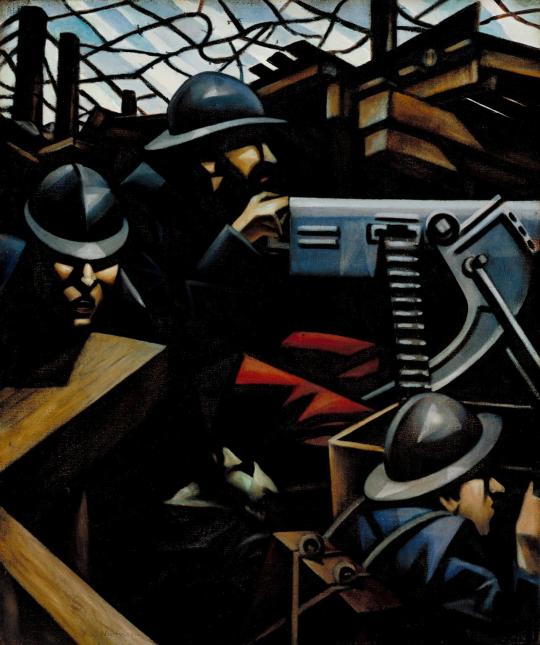

C.R.W Nevinson – La Mitrailleuse, 1915

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson was a fascinating man who in life and letters seems paranoid and jealous of the success of others, no matter how well he himself was doing. Many of his friends he drove away in one way or the other due to his incredible ability to take offence. In 1920, the critic Charles Lewis Hind wrote that:

‘It is something, at the age of thirty one, to be among the most discussed, most successful, most promising, most admired and most hated British artists.†

He studied at the Slade art school alongside Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, John Currie, Edward Wadsworth, Rudolph Ihlee, Adrian Allinson and Dora Carrington.

His time at the Slade was unhappy, the tutor Henry Tonks hated his work, he and Gertler fell in love with Dora Carrington (as did most men it seems) and their strong friendship was shattered when Carrington started having intercourse with Gertler.

His work however was visual and strong and he was inspired by the Italian Futurists, Cubists and his work follows themes of the Vorticists, even though he was not a member of the group after irking Wyndham Lewis.

After a brief stint as a journalist he went back to art. At the outbreak of World War I, Nevinson joined the Friends’ Ambulance Unit and was deeply disturbed by his work tending wounded French soldiers in Flanders. For a very brief period he served as a volunteer ambulance driver before ill health forced his return to Britain. Subsequently, Nevinson volunteered for home service with the Royal Army Medical Corps. He used these experiences as the subject matter for a series of powerful paintings which used the machine aesthetic of Futurism and the influence of Cubism to great effect. His fellow artist Walter Sickert wrote at the time that Nevinson’s painting:

Mr Nevinson’s Mitrailleuse, which will probably remain the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting. This must be for the nation. ‡

In 1917, Nevinson was appointed an official war artist, but he was no longer finding Modernist styles adequate for describing the horrors of modern war, and he increasingly painted in a more realistic manner to the point that ’Paths Of Glory, 1917’ was censored from display.

The First World War was one were that artists embraced Printmaking due to the lack of materials at hand, it saw the medium rise up from trade and advertising to one of art. Nevinson’s prints of WW1 were lively, hellish and futuristic.

Nevinson’s printmaking is unique in a number of ways. He was virtually the only artist who was directly concerned with Modernism to use etching and mezzotint. Every other important artist in this regard turned to wood engraving, cutting, or lithography, perhaps to break away from the established traditional etchers with whom they did not wish to be associated. Nevinson actually only attempted two woodcuts.

During the years 1916-19, Nevinson was instrumental in establishing modern ideas in British printmaking, which should be seen in the context of Vorticism, and Nevinson’s own earlier painting. Another antecedent was Edward Wadsworth’s woodcuts. ♠

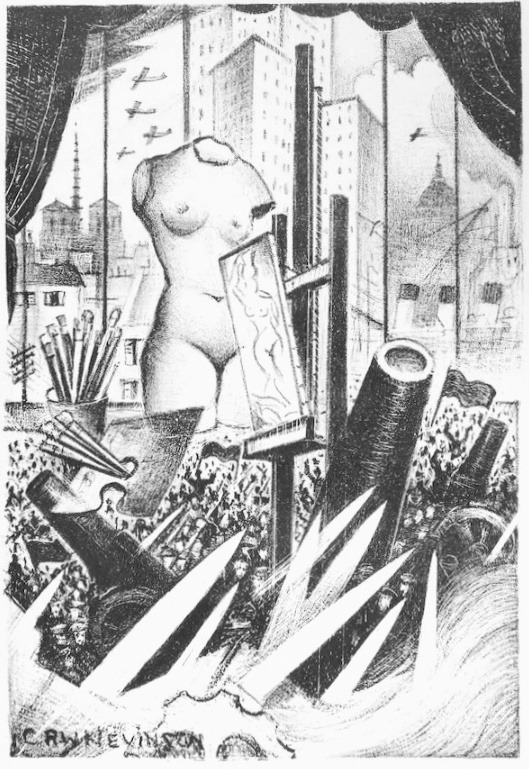

C.R.W Nevinson – The Spirit Of Progress, 1915

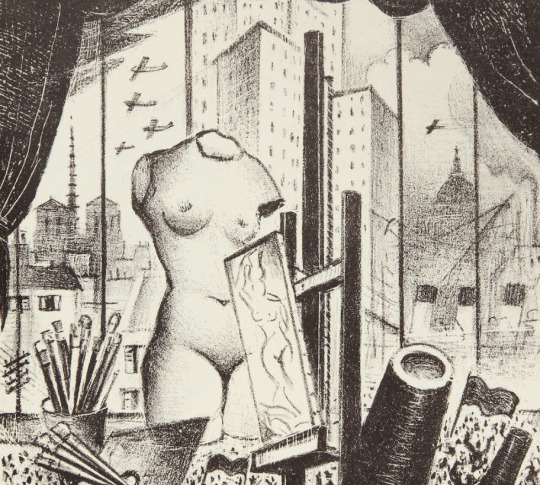

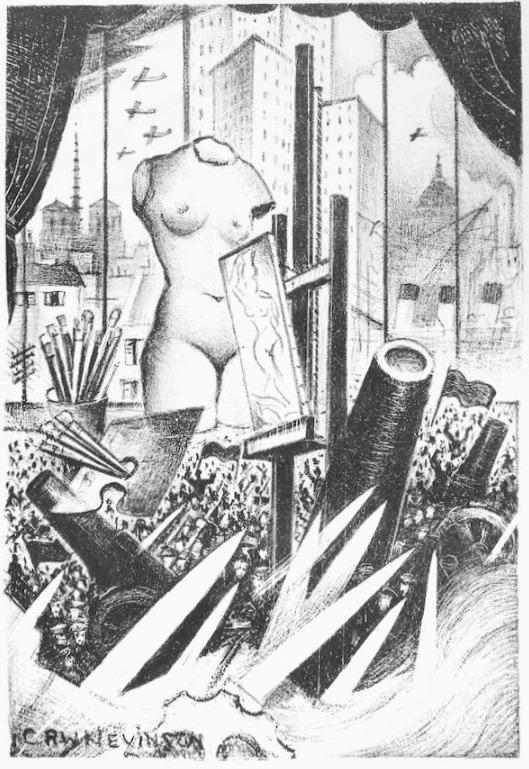

However, this post is about the lithograph by C.R.W.Nevinson made in 1933 called ‘The Spirit Of Progress’. It is an iconic yet strange picture, almost a greatest hits of Nevinson’s artworks of the previous twenty years.

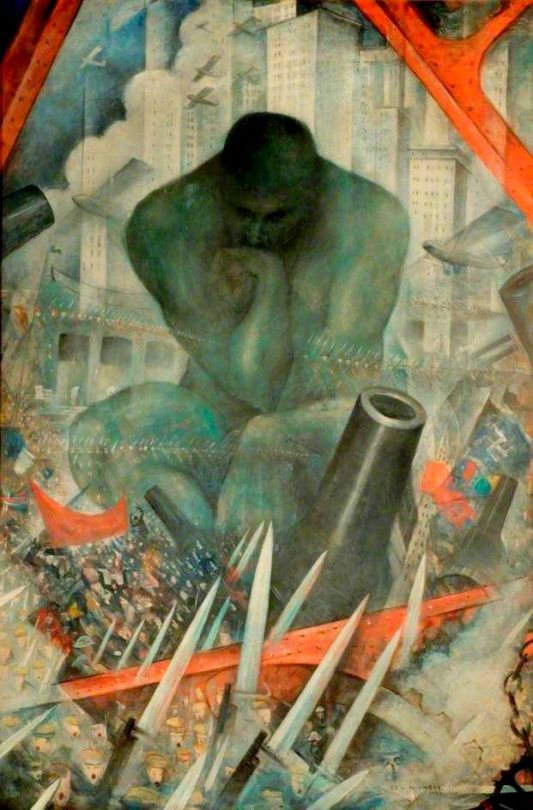

The arrangement of ‘The Spirit Of Progress’ is one Nevinson would visit many times. In ’Twentieth Century’ the Thinker by Auguste Rodin is in the centre of a war and skyscraper combination of airplanes and weaponry.

C.R.W Nevinson – Twentieth Century

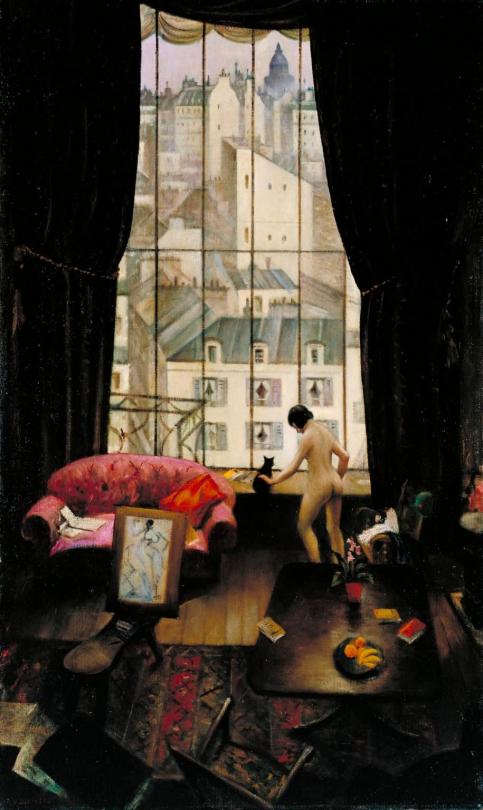

‘The Spirit Of Progress’ takes place on the seventh floor of the Paris studio of the author and journalist Sisley Huddleston, as seen in the painting ‘A Studio in Montparnasse’, with the windows, curtains from this setting.

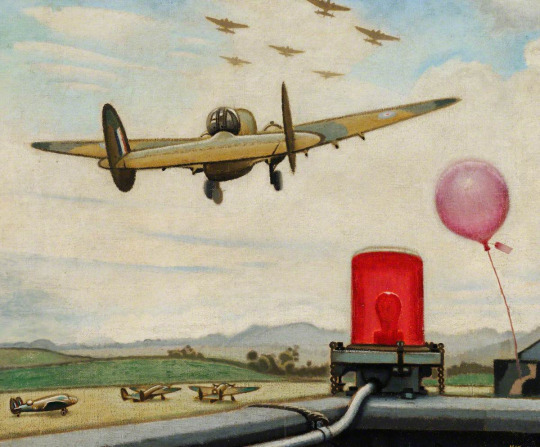

C.R.W Nevinson – A Studio in Montparnasse, 1925

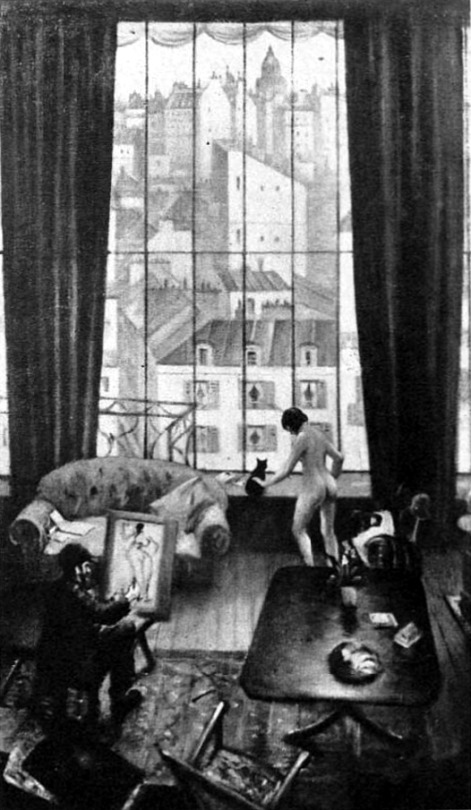

Curiously enough the painting ‘A Studio in Montparnasse’ was exhibited at Leicester Galleries in March 1926 as though it were finished but after the exhibition Nevinson repainted areas of it, adding a swagger to the curtains and removing the artist painting the nude. The original version is pictured below from The Sketch newspaper.

C.R.W Nevinson – A Studio in Montparnasse, from The Sketch, 3 March 1926

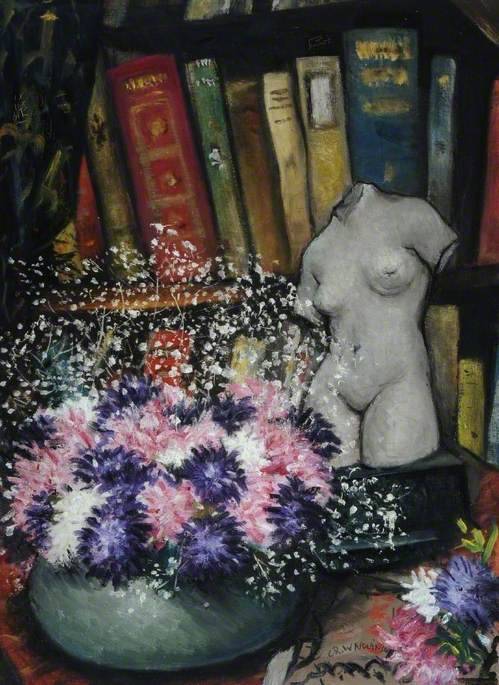

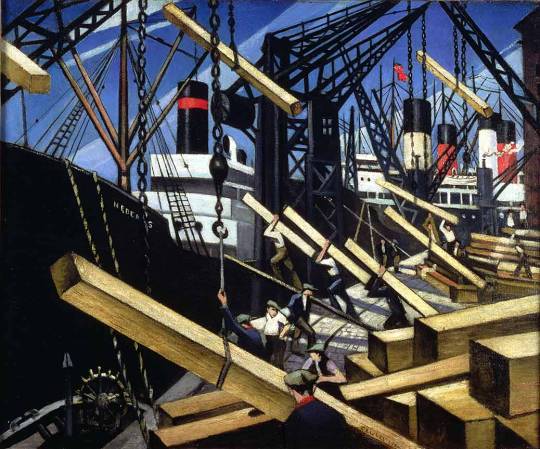

When Huddleston saw the painting he was outraged of the addition of the nude model. In ‘The Spirit Of Progress’ the painting of the model is kept but is replaced with a stone Aphrodite of Milos like figure. In the painting ‘Asters’ the model is shown as a small piece of sculpture on the artists desk, though a mirror image, a print is the reverse of how it is drawn. This also happened when Nevinson transcribed ‘Loading Timber, Southampton Docks’ into the print ‘Dock Workers Loading’ it is a mirror image of the painting, being drawing as a print, the same as the painting and reversed in the printing.

C.R.W Nevinson – Asters

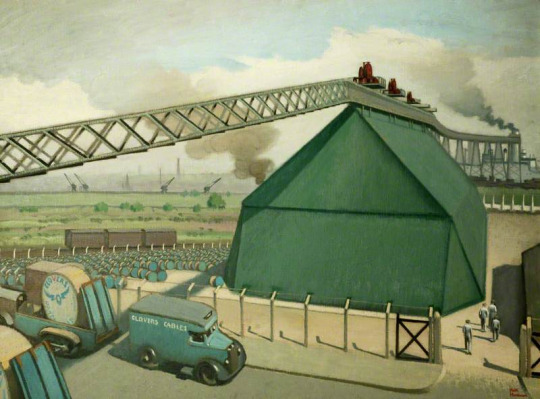

As above – outside the window to the right are the funnels of an ocean-liner, the type that Nevinson painted below in 1916 with the cranes for the docks.

C.R.W Nevinson – Loading Timber, Southampton Docks, 1917.

C.R.W Nevinson – Dock Workers Loading, 1917.

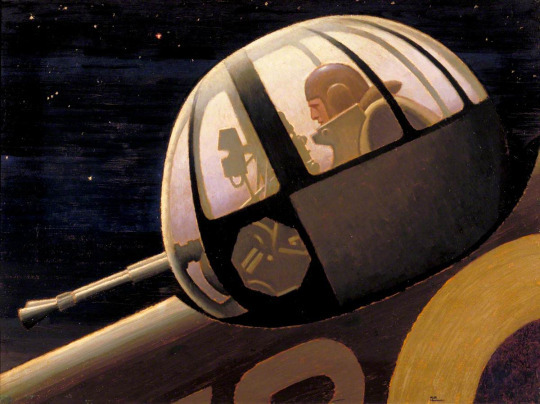

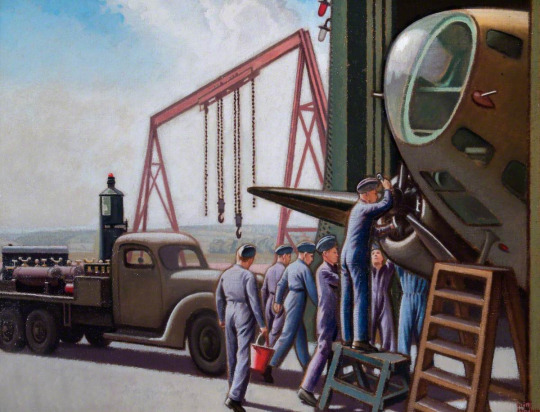

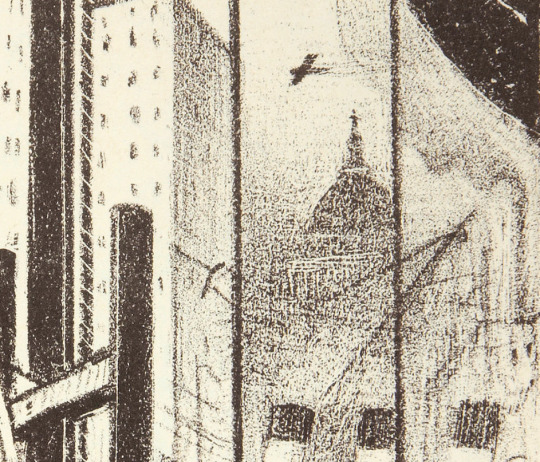

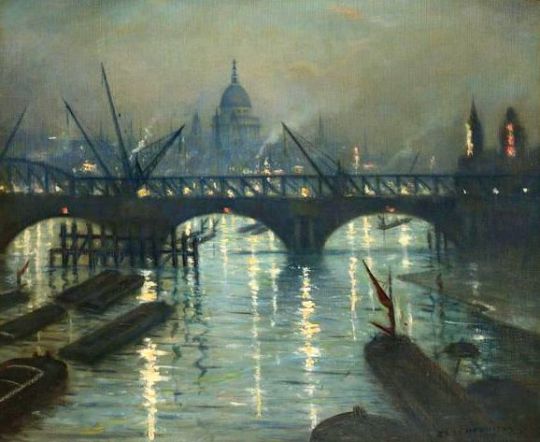

Above the ocean-liner in the mist is St Pauls, Nevinson painted the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral many times from different view points. Planes fly over head, not the Blitz yet, as ‘The Spirit Of Progress’ dates from 1933. It was the early days of aviation and airline travel and aircraft had been used in the World War One as Nevinson was sent up, Biggles style to draw the De Havilland D.H.2 planes in Dog Fights.

C.R.W Nevinson – City of London from Waterloo Bridge, 1934

C.R.W Nevinson – St Paul’s from the South

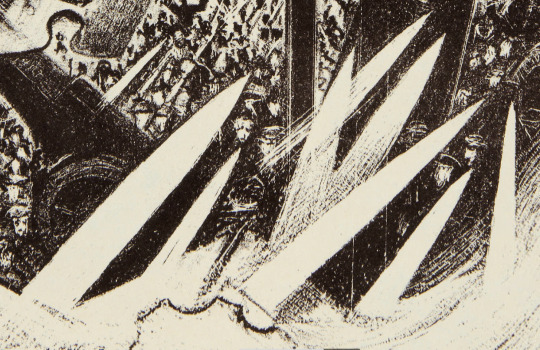

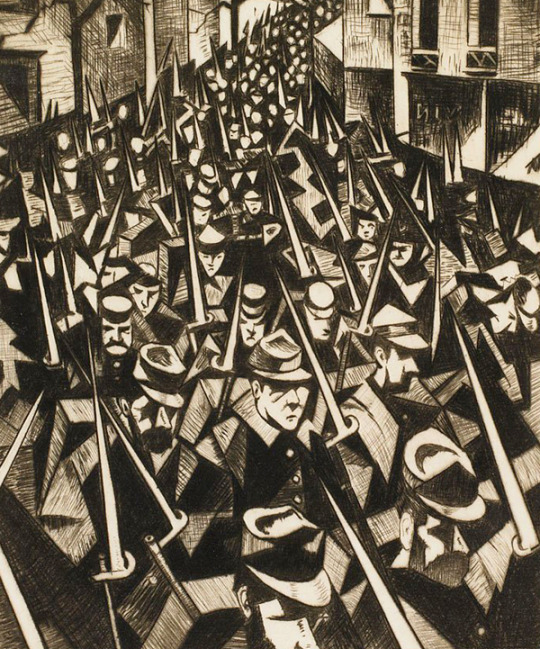

The Bayonets shown are found in many of Nevinson’s First World War pictures, below is an etching of French infantrymen matching though a town. As it is an early picture from the war it is more Futurist in style. The same can be said of ‘Returning to the trenches’, a painting of men marching off into the distance.

C.R.W Nevinson – A Dawn, 1914.

C.R.W Nevinson – Returning to the Trenches, 1914

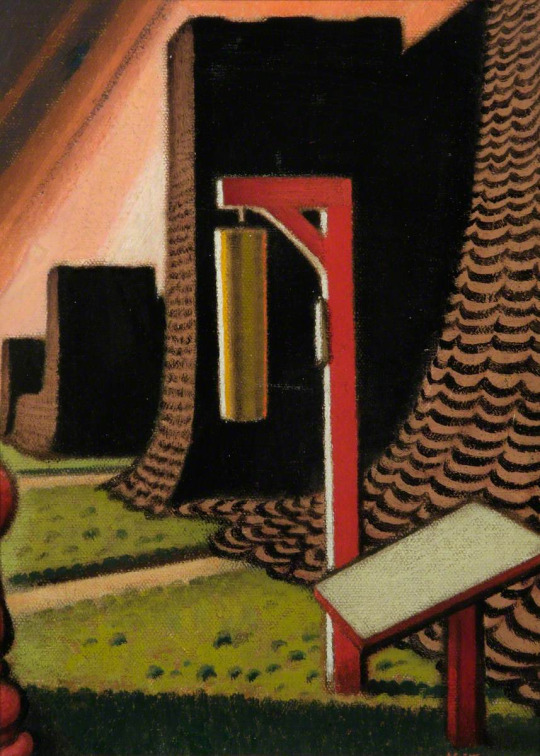

At the base of the the picture is a Howitzer Gun among the bayonet knives. Nevinson painted the gun on its own in a ‘A Howitzer Gun in Elevation’. A mechanical and rather Futuristic painting. The First World War being about the machines and not the humans operating them.

C.R.W Nevinson – A Howitzer Gun in Elevation, 1917

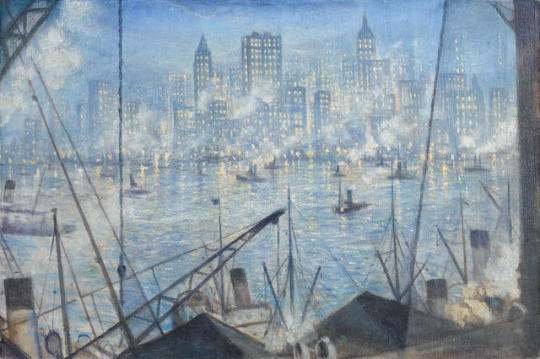

C.R.W Nevinson – New York, Night, 1920.

Nevinson was invited to New York in 1919 by David Keppel of the print publishers Frederick Keppel and Co, to exhibit his War prints. Manhattan’s architecture inspired him, not only by the sheer beauty of its sky-scrapers. ♣

It is interesting to see what then happened between the first and second exhibition in New York. When Nevinson first went to New York, it was as a war hero, a survivor and documenter of war in a bold new ‘futurist’ way. And the first exhibition was a success.

He was clearly captivated by the city, compared to the London of the 1920s it must have been something, the skyscrapers of the day in New York would have been the Woolworth Building (60 stories) and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower (50 stories), but most of the ‘skyscrapers’ of the early 1920s peaked around 30 stories tall. London didn’t start building above 20 stories until the 1960s. Nevinson is quoted below:

‘New York, being the Venice of this epoch, has triumphed, thanks to its engineers and architects, as successfully as the Venetians did in their time.. Where the Venetian drove stakes into his sandbanks to overcome nature, the American has pegged his city to the sky. No sight can be more exhilarating and beautiful than this triumph of man. ♥

His second exhibition was a series of paintings and etchings of New York that failed to capture the attention of the public. The press were kind but the works did not sell well and there is little reporting of the second exhibition in comparison to the first.

Below is an extract from the New York Herald, 24th October, 1920.

“Art,” says Mr. Nevinson, “triumphs in utility, and the most beautiful products of

the modern world are a Rolls-Royce car and a skyscraper. They have been built for strict utility; their lines are perfect and they must appeal to the genuine artist. New York will be remembered for its introduction of the architecture of the skyscraper long after its people have been forgotten for other things.” ◊

New York should like Mr. Nevinson and his work, for surely he Is her friend. No

native could ever idealize America’s greatest city more than this foreigner. ◊

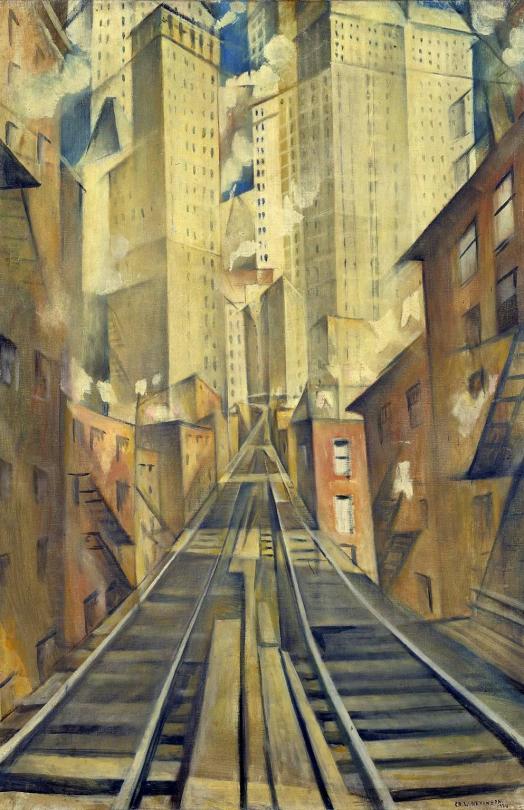

C.R.W Nevinson – The Soul of the Soulless City, Previously known as New York – an Abstraction ,1920.

The poor reception of this exhibition may have accelerated Nevinson’s disaffection with the city. His growing embitterment is perhaps reflected by the change of title. Originally exhibited in 1920 at the Bourgeois Galleries, ‘New York, as New York – an Abstraction’, it was re-titled ‘The Soul of the Soulless City’ in the Faculty of Arts Exhibition, Grosvenor House, London, in 1925 probably at Nevinson’s instigation. ♦

‘The Spirit Of Progress’ has all the motifs mentioned above and of all my Nevinson prints is my favourite.

† M J. K. Walsh – A Dilemma of English Modernism, 2007

‡ Walter Sickert – Burlington Magazine, The True Futurism – April – 1916

♠ Robin Garton – British Printmakers 1855 – 1955, 1992

♣ C.R.W. Nevinson 1889 – 1946 Retrospective Exhibition Of Paintings, Drawings And Prints: Kettle’s Yard Gallery 1988

♥ David Cohen – C.R.W. Nevinson, The Twentieth Century, p46, 1999.

◊ New York Herald, 24th October, 1920.

♦ Tate, London, T07448.