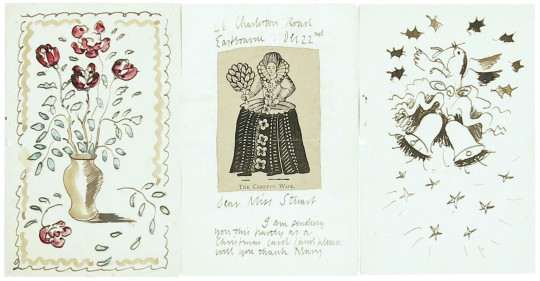

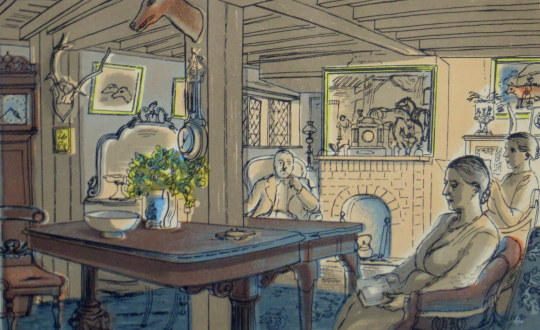

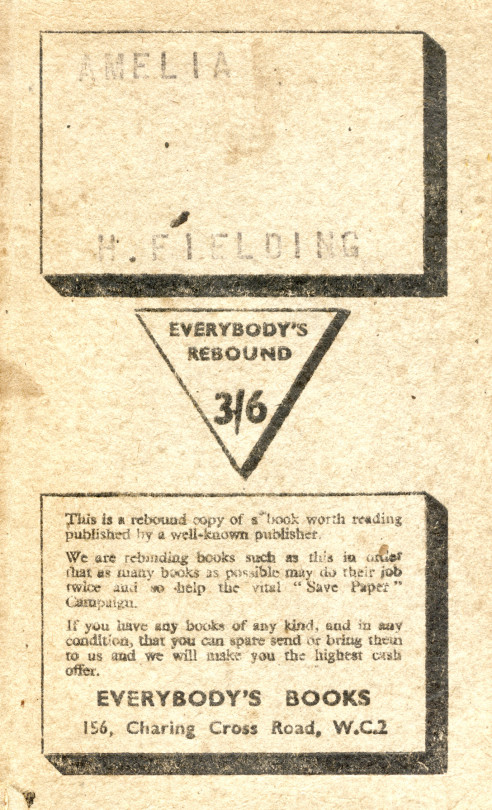

I bought this book the other day, it is Amelia by Henry Fielding from 1906, published by George Bell and Sons, later rebound by ‘Everybody’s Rebound’, run by the publishers Everybody’s Books. On the cover is this:

– This is a rebound copy of a book worth reading published by a well-known publisher.

– We are rebinding books such as this in order that as many books as possible may do their job twice and so help the vital “Save Paper” Campaign.

– If you have any books of any kind, and in any condition, that you can spare send or bring them to us and we will make you the highest cash offer.

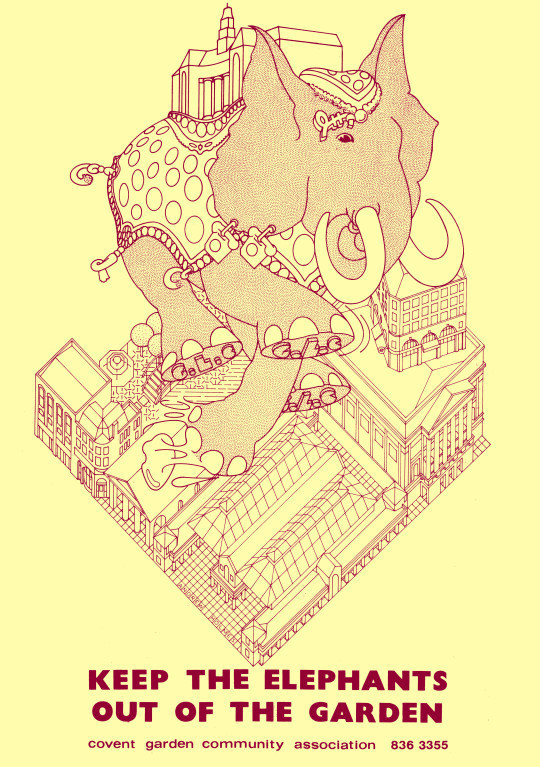

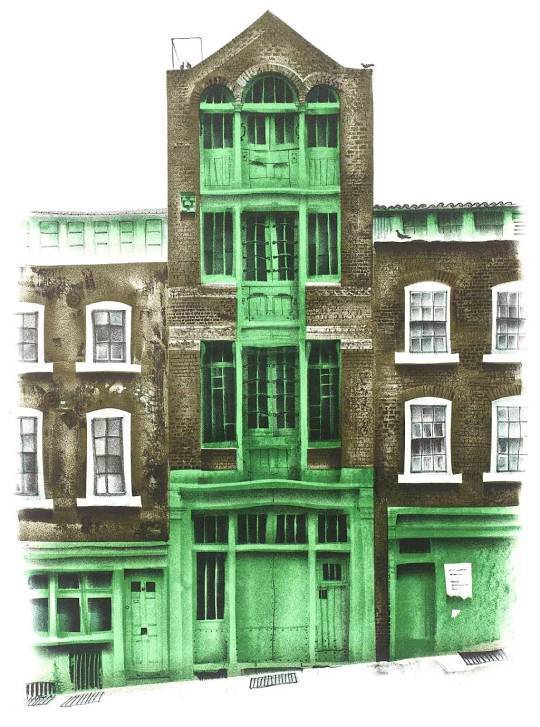

I can only guess the Save Paper Campaign was from the Second World War. Everybody’s Books were based at 156 Charing Cross Road and 4 Denmark Street. It was a cunning idea to take old books and re-brand them as their own. As one thing leads to another… The building of the publishers has a curious history.

The Rolling Stones recorded at Regent Sound Studio based at 4 Denmark Street.

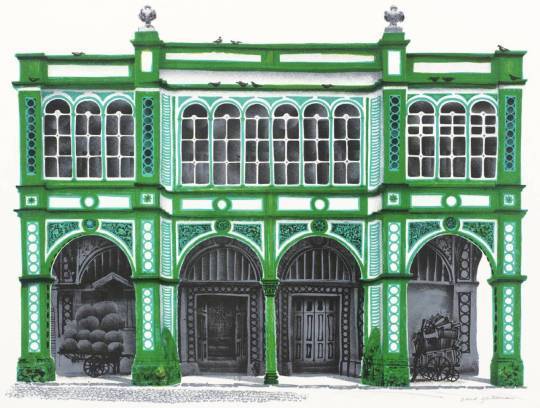

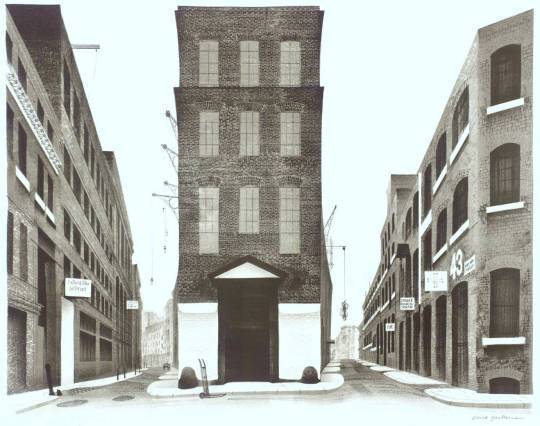

156 Charing Cross Road has now been demolished but stood close to Centre Point in London. The building was taken by George Allen. In 1890 Allen opened a London publishing house at 8 Bell Yard, Chancery Lane; and in 1894 he moved to a larger place at 156 Charing Cross Road. There he took to general publishing, though Ruskin’s works remained the major part of his business. He died in 1907 but the publishing house Allen and Unwin lives on. While there George Allen named the building Ruskin House.

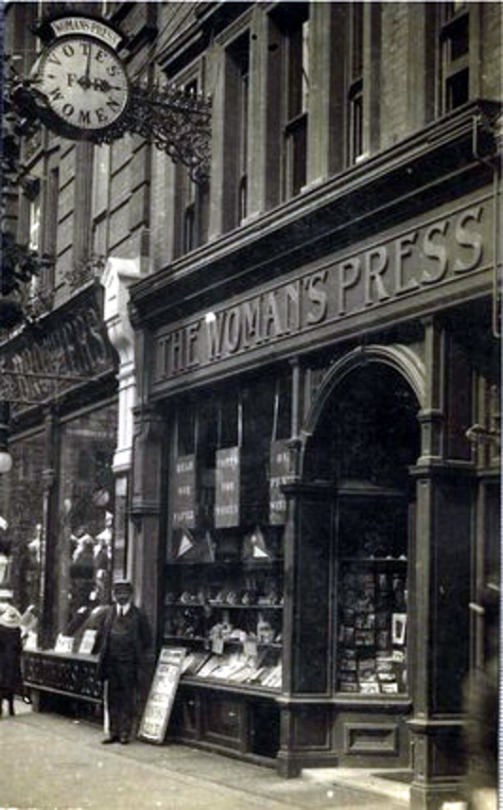

Some time in 1909 George Allen moved from the building. The offices of the building were then occupied by the Woman’s Press from 5 May 1910 until October 1912. Established in 1907, the Woman’s Press has been described as “..an all-encompassing, self-funding propaganda division” of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The premises at Charing Cross Road constituted a shop at ground floor level, and offices of the Woman’s Press above. The shop stocked a range of campaign-themed goods such as ribbons and rosettes, as well as other items like tea and soap which featured their motto ‘Votes for Women’. The upstairs offices housed the WSPU’s wholesale and retail operations, however the editorial division remained based at the union’s Clements Inn headquarters. Despite its name, the printing was largely undertaken by St Clements Press near Clements Inn.

It is likely that after the WSPU came Everybody’s Books in the late 30s.

The Woman’s Press, Ruskin House, 156 Charing Cross, London.