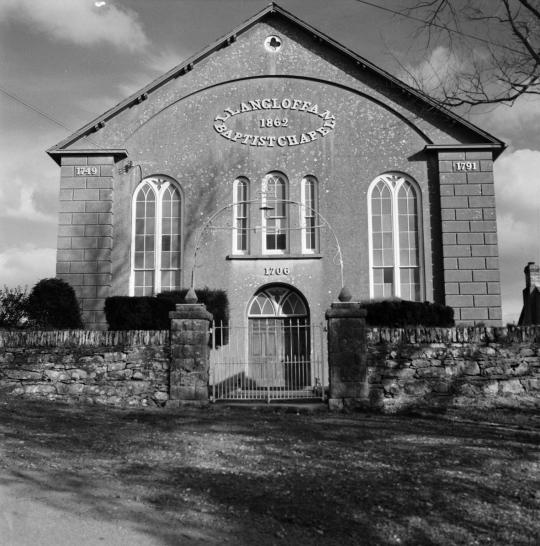

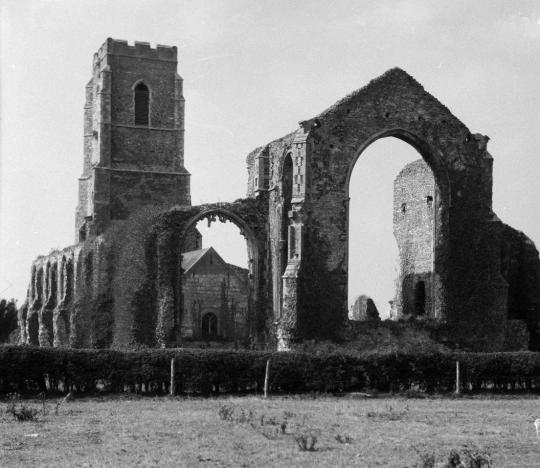

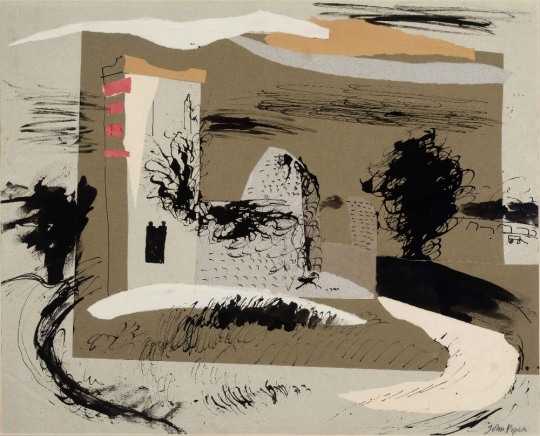

Here are two photographs by John Piper and two paintings, both in different styles. They focus on the such of St Clement’s, in Terrington St Clement. A large village in Norfolk, England. It is situated in the drained marshlands to the south of the Wash, 7 miles west of King’s Lynn, Norfolk, and 5 miles east of Sutton Bridge, Lincolnshire, on the old route of the A17 trunk road.

As well as showing the different artistic techniques for one subject, it also shows how Piper used his photographs as a visual reference when back in his studio (as I noted in the post ‘Lens and Pens’).

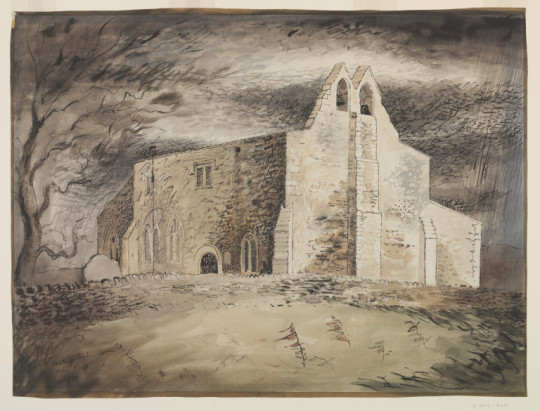

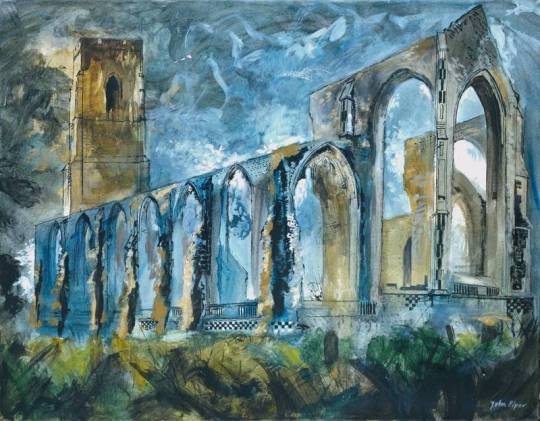

John Piper – Terrington St Clement Church, 1975.

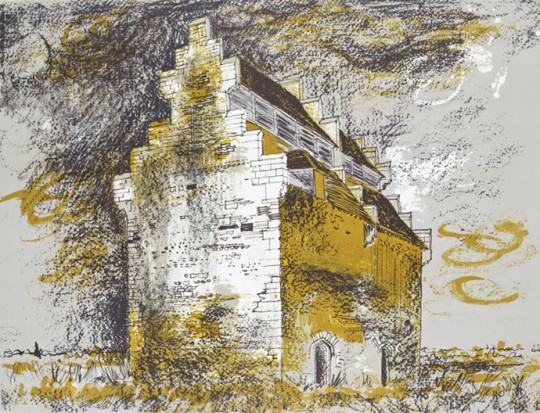

Five years apart between them both, the 1975 painting is a classic Piper picture and I am amazed it wasn’t editioned into a screen-print as the levels of detail in it are remarkable, the blocked out lighter panels of the windows and reversed light outline of the bell tower against the typical Piper sky.

John Piper – Terrington St Clement Church, Norfolk.

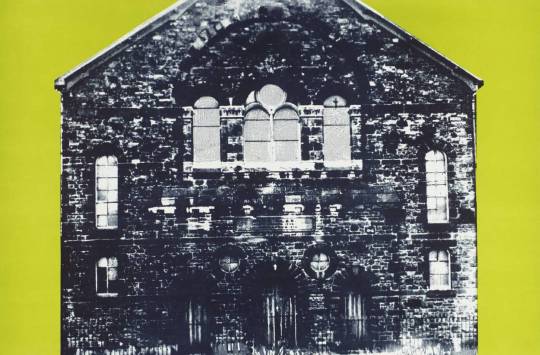

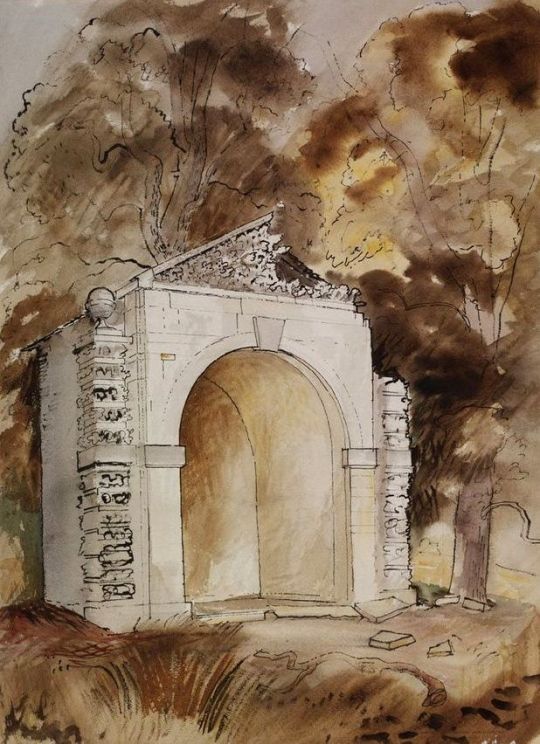

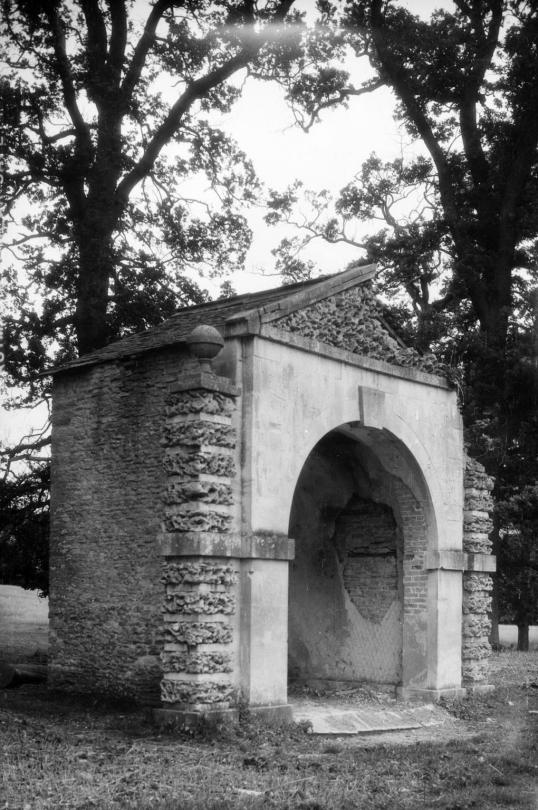

John Piper – Knowlton Church, Dorset, 1938

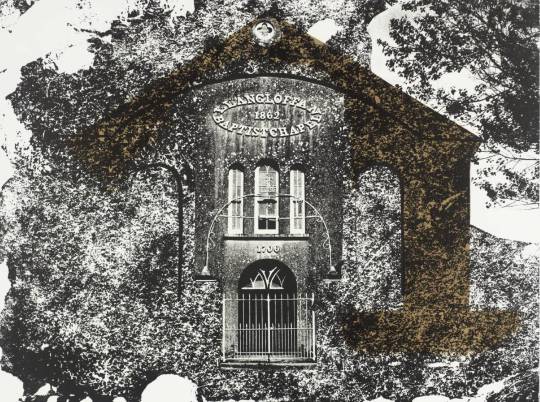

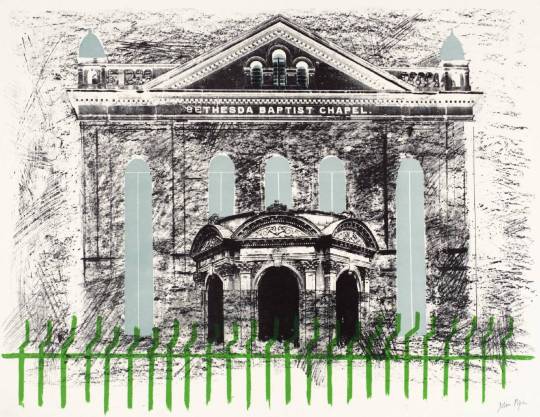

The picture below from 1980 is far more abstract and wild with colour. It is looking more like a study of a painting. The outlines and abstracted features of the building draughtsmanship are typically Piper. Although the colouring may not look like his works at that time, I would suggest they are a throwback to when Piper used collage in the 1930s. As with the Knowlton Church collage, blocks of colour are used with outlines. It makes an interesting marriage of new and old techniques.

John Piper – Terrington St Clement Church, 1980

John Piper – Terrington St Clement Church, Norfolk.

Below is a video I found on Youtube of a drone flight around the church, I wonder what Piper would have made of such a technology?