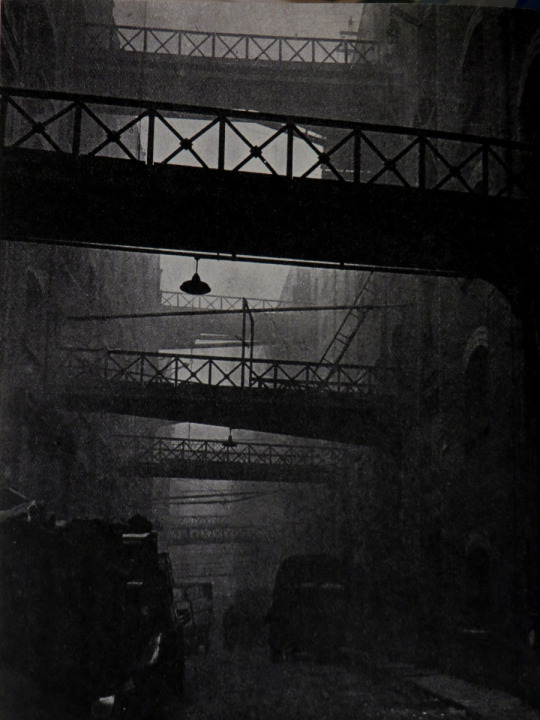

Covent Garden Market in London has a varied history that came to a head in the 1960s. Traffic to and from the market for buyers and traders was bothersome enough with narrow horse carts but with larger cars and lorries it was a nightmare.

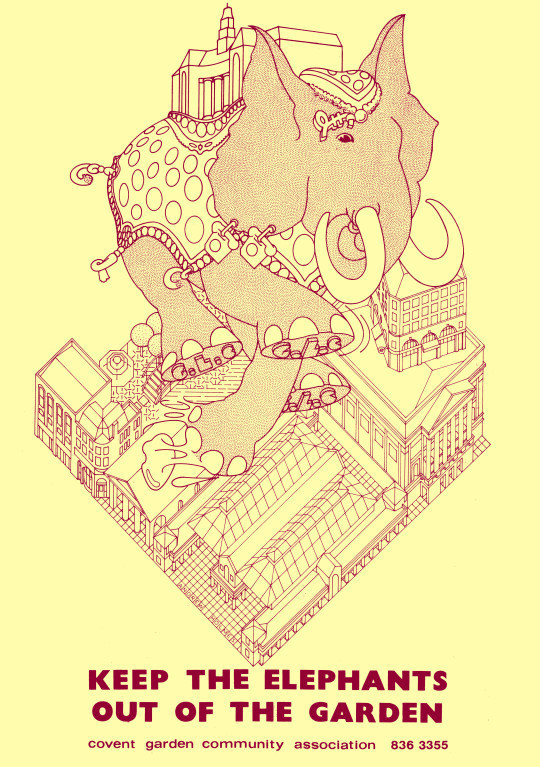

In 1961 the Covent Garden Market Bill was passed, there was some deliberation on what would happen to the historic buildings of Covent Garden after that. Redevelopment plans arose, and for ten years these plans were fiercely fought by the Covent Garden community, arguing in favour of preserving the area for its historical value and cultural meaning.

The Elephant being the GLC for Greater London Council, trampling on the area.

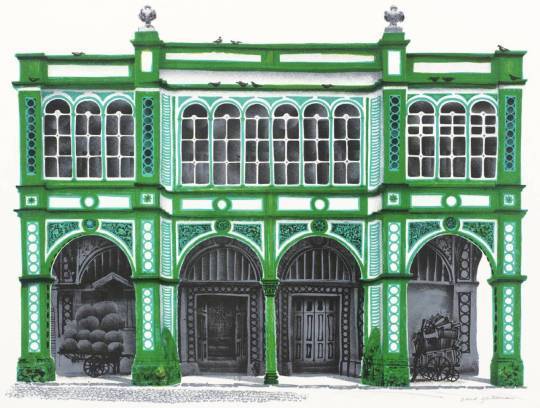

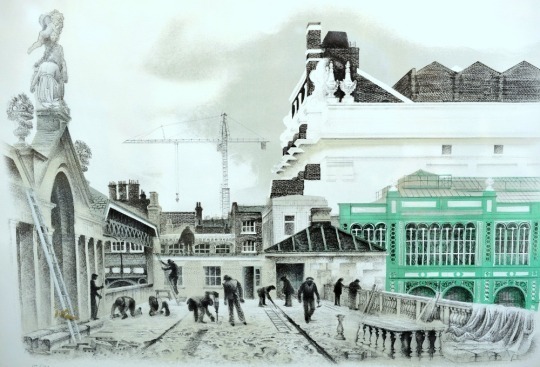

Their victory in this battle preserved Covent Garden’s old market buildings and they were reopened as a major tourist and shopping destination in 1980. The market had to be moved in its entirety across the river to Nine Elms in 1974 but the original buildings were preserved. Below are the responses to the closure and artistic propaganda by David Gentleman to show the beauty of the area.

By the end of the 1960s, traffic congestion had reached such a level that the use of the square as a modern wholesale distribution market was becoming untenable, and significant redevelopment was planned. Following a public outcry, buildings around the square were protected in 1973, preventing redevelopment. The following year the market moved to a new site in south-west London. The square languished until its central building re-opened as a shopping centre in 1980.

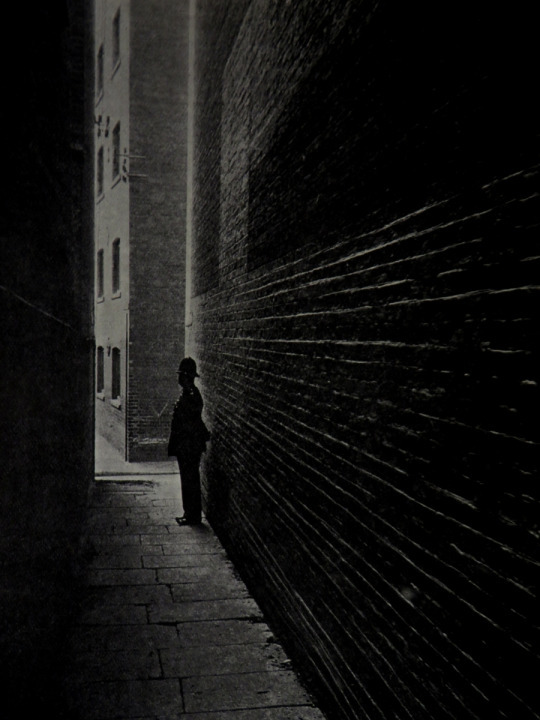

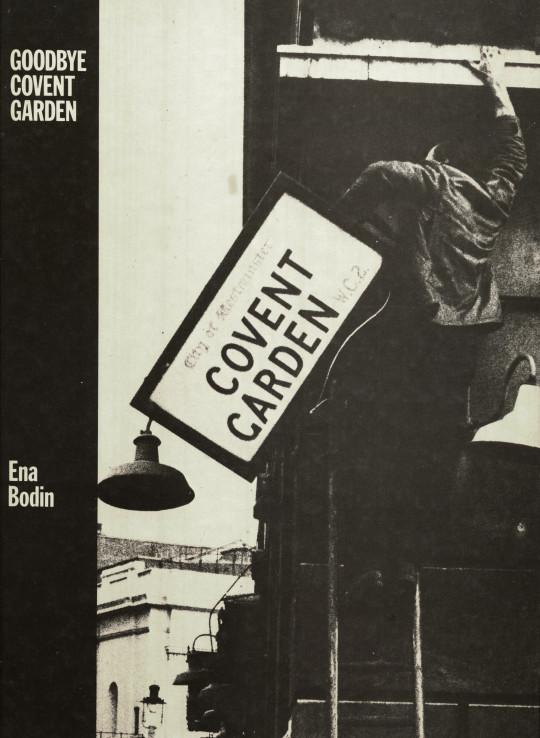

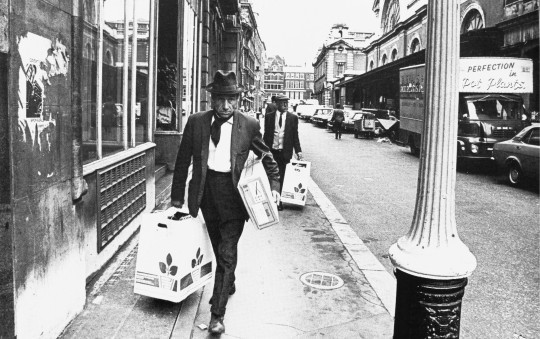

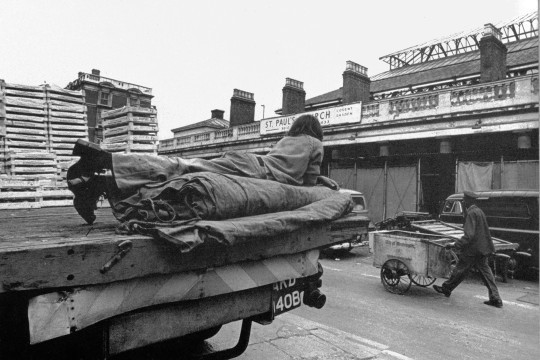

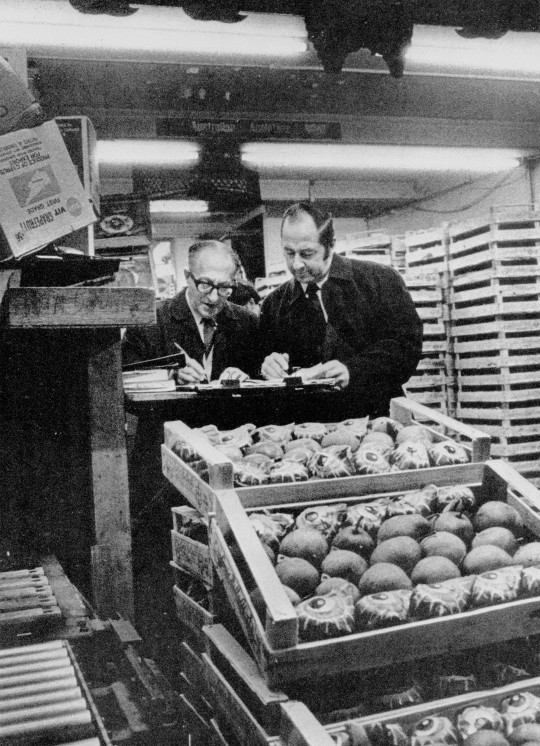

Goodbye Covent Garden was a photobook published in 1975 by Oxford Illustrated Press. It featured photographs of the workers and people around Covent Garden taken by Ena Bodin in the last two years of the market. Other than the cars and beautiful signage in the photographs you can see some of the mens fashions and even in some cases – platform shoes.

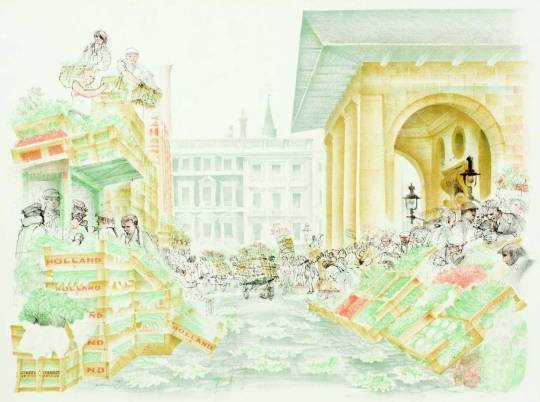

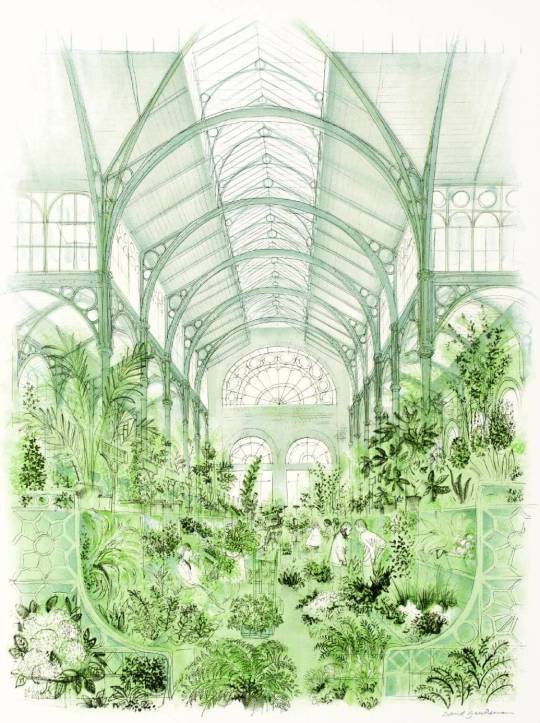

Above the picture shows the original Market building in use and below you can see the beautiful lithographs by David Gentleman.

David Gentleman – Foreign Fruit Market, 1972

David Gentleman – Southern Section of Piazza (James Butler), 1972

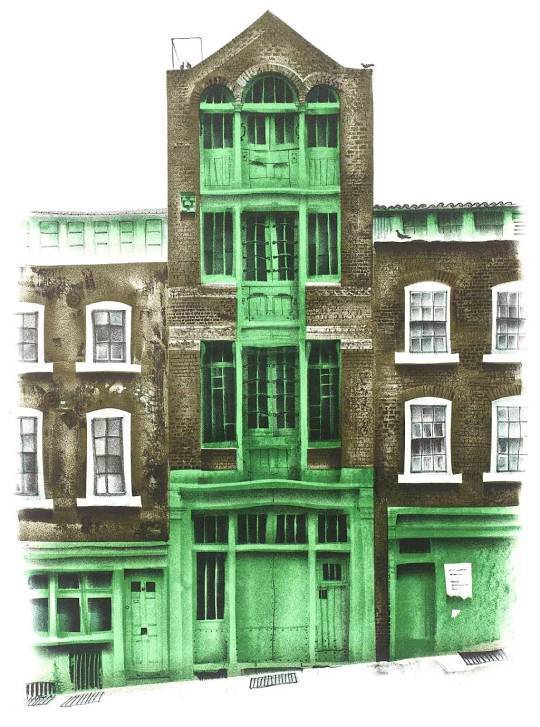

David Gentleman – East Terrace, 1972

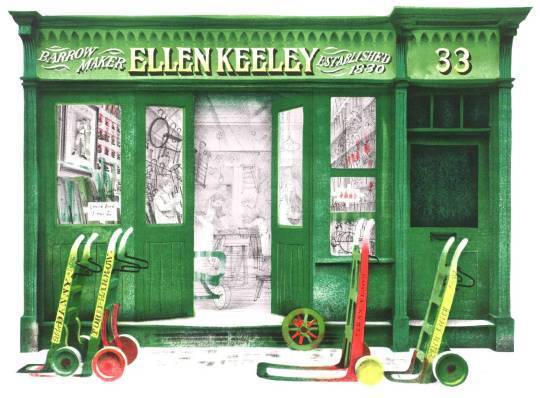

David Gentleman – Ellen Keeley’s Shop, 1972

The main premises of barrow-making firm of Ellen Keeley est. in Ireland in 1830. The Keeley family came to England at the time of the potato famine and lived in Nottingham Court. James Keeley invented and produced the costermonger’s barrow, like a shop on wheels and also developed the donkey barrow, once a familiar sight in London. In 1891 he was living at No.12 Nottingham Court and the elderly costermonger Ellen was living alone at No.8. In the 1960s the firm branched out into hiring their vehicles to the film industry (Keeley Hire in Hoddesdon).

Ellen Keeley’s Shop, 33 Neals Street, 2017.

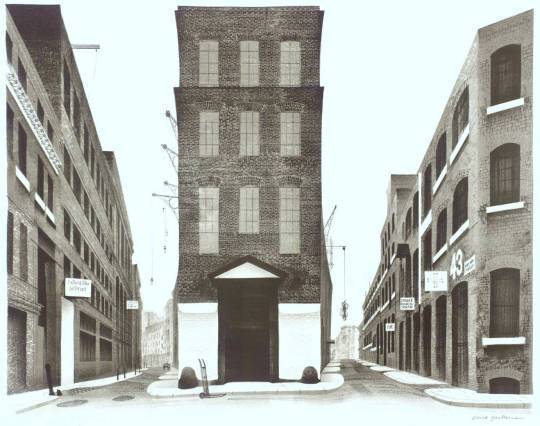

David Gentleman – Warehouses between Shelton St and Earlham St, 1972

David Gentleman – Piazza Looking South Past St Paul’s, 1972

David Gentleman – Warehouse in Mercer St, 1972

David Gentleman – The Flower Market, Covent Garden, 1972

The photography in this post is more of a defeat than a triumph, it is the documenting the end of something. The works of David Gentleman however placed along-side these photos show that Gentleman’s lithographs were able to inspire a vision of the area, making the dishevelled and shabby, romantic. Much like an Eric Ravilious painting. In making the lithographs I believe that Gentleman helped to present a case for the areas protection amongst the artists and lovers of conservation at the time when a spotlight was being put on the East End and Spitalfields.