Many people might be unaware that Paul Nash did portraits, few are finished works but some are in illustrated letters. To me they are rather pleasing and the dress and hair of the sitters is also of the era. I picture them being drawn in a 1930s sitting room by a fire.

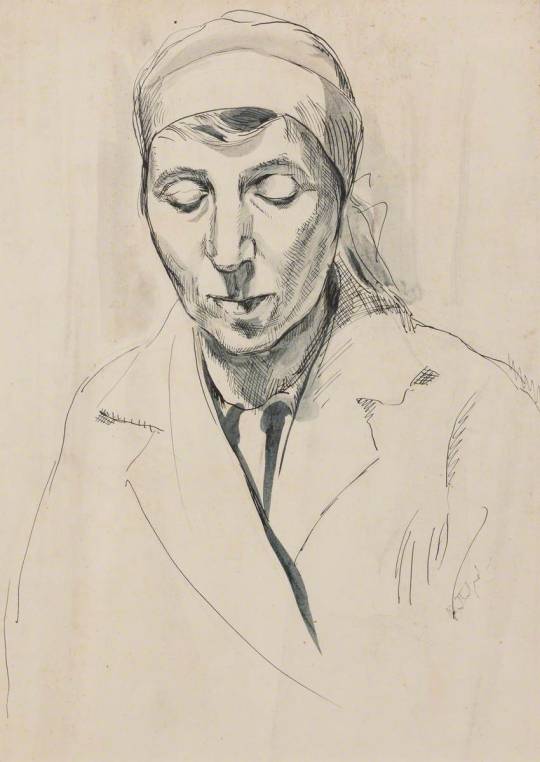

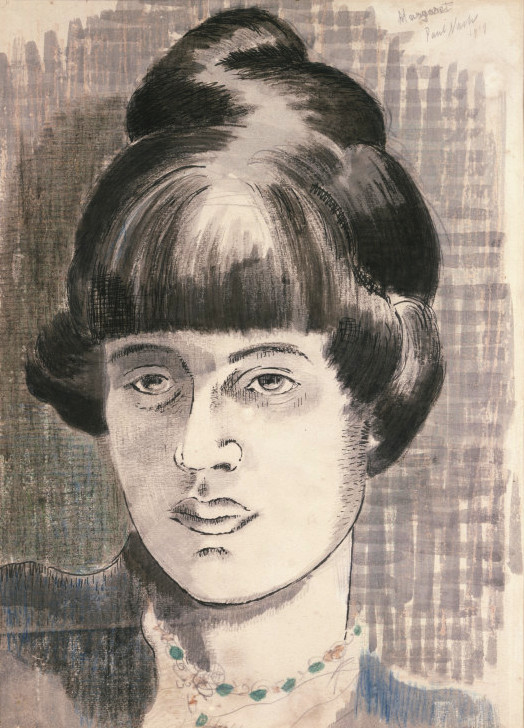

Paul Nash – Margaret Nash, 1919

Margaret Theodosia Odeh was born in Jerusalem, Nash grew up in Cairo. She was the daughter of an Anglican minister. Shortly after moving to London in 1908, she became involved in the suffrage movement and the Tax Resistance League. One of the founding members of the Committee for Social Investigation and Reform, Nash offered rehabilitation and opportunities for women working as prostitutes. With funding from donors including Millicent Fawcett and Elizabeth Anderson, the Women’s Training Colony in Berkshire was established. Women could stay at the retreat and learn arts and crafts, including millinery. The initiative was inspired by the Arts and Crafts objective to improve people’s lives through craft. She also worked on textiles at the Omega Workshops run by the Bloomsbury group. She married Paul Nash in 1913.

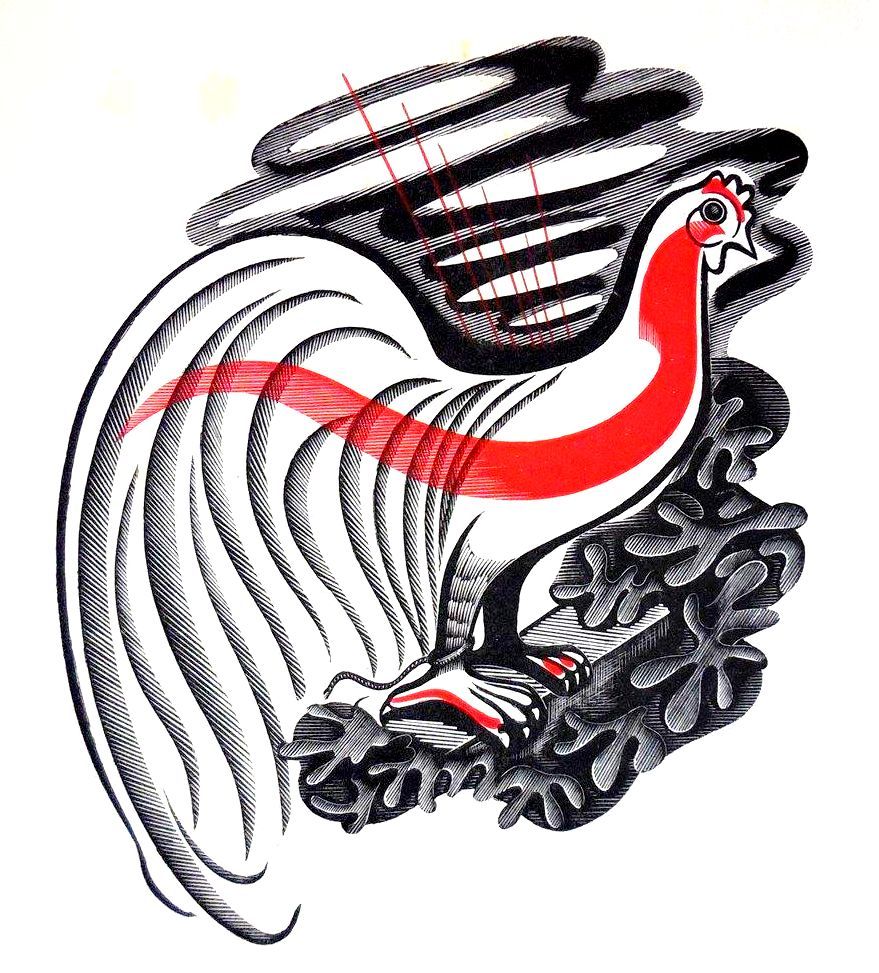

Paul Nash – Portrait of Alice Daglish, 1921

Alice (nee) Archer is known mostly for The Land of Nursery Rhyme, 1932, a book she co-edited with Ernest Rhys. It was illustrated by Charles Folkard. She married Eric Fitch Daglish in 1918 and lived to be 103.

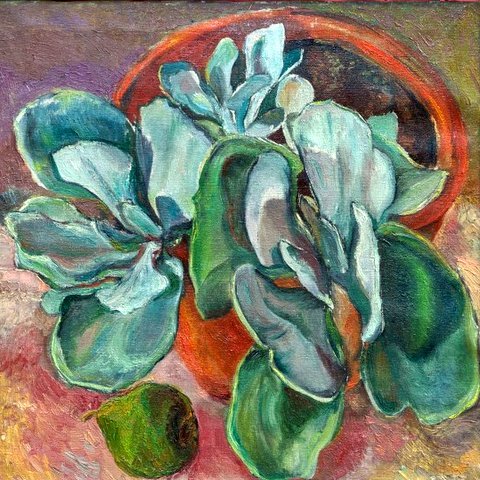

Paul Nash – Yvonne, 1922 (Maybe Yvonne Gregory)

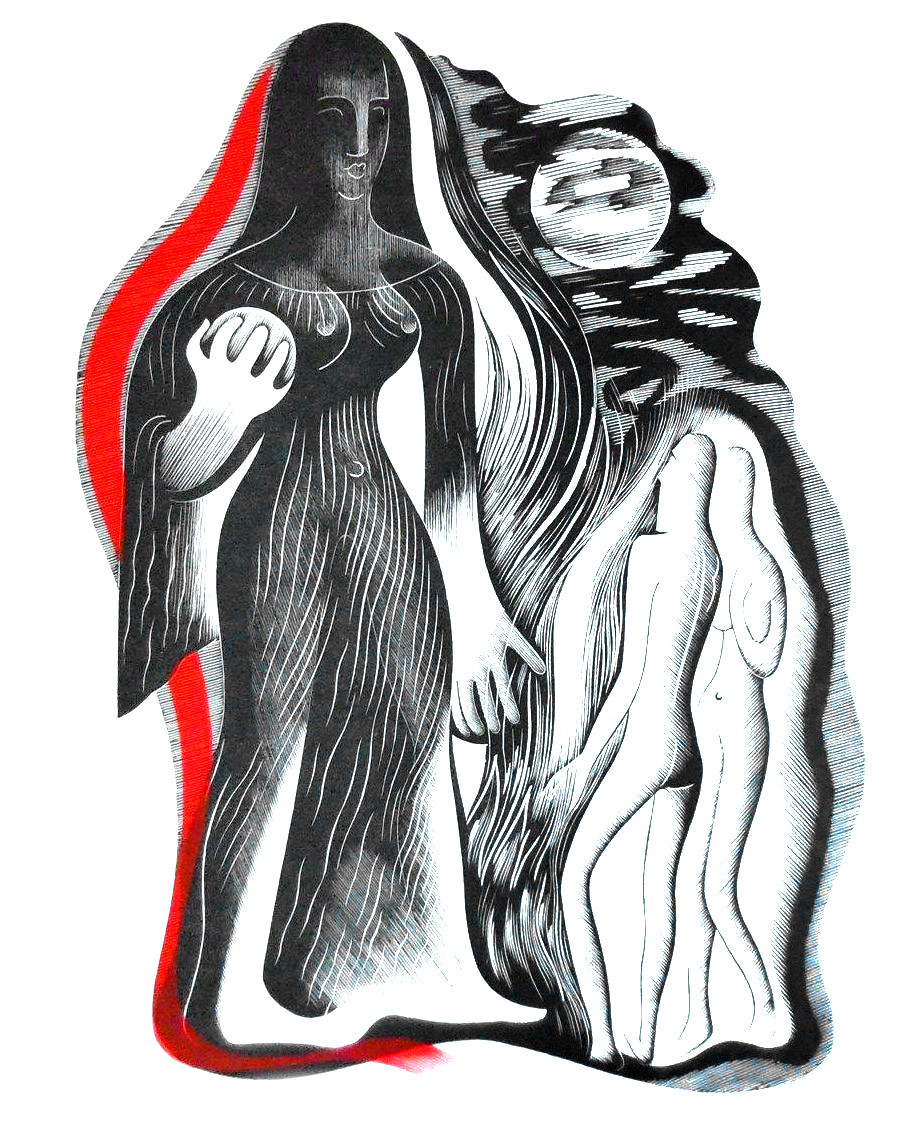

Paul Nash – Douglas Goldring

Douglas Goldring was an English writer and journalist. He became known mostly as a travel writer. In the late 1930s Goldring came to prominence in two ways. He was Secretary of the Georgian Society, which he helped to found after writing in the Daily Telegraph in 1936, with Lord Derwent and Robert Byron. Inspired by the ideas of William Morris, Goldring helped transform it in 1937 into the Georgian Group, a section within the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, on the advice of Lord Esher.

Goldring soon became unhappy with the Georgian Group’s political conservatism and left it. He was also noted, at the same period, as a radical journalist and prolific contributor to left-wing publications. Goldring described his political views as socialist. In his last years, Goldring contributed reviews to the Socialist Labour League magazine Labour Review.

Paul Nash, Barbara, c1910

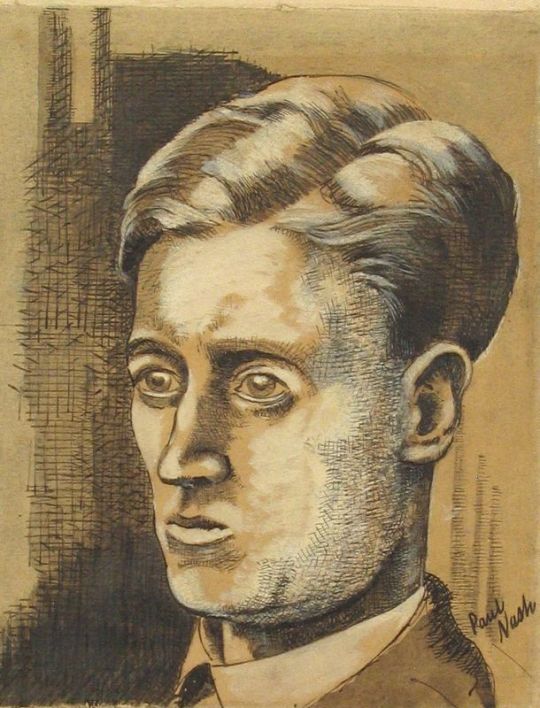

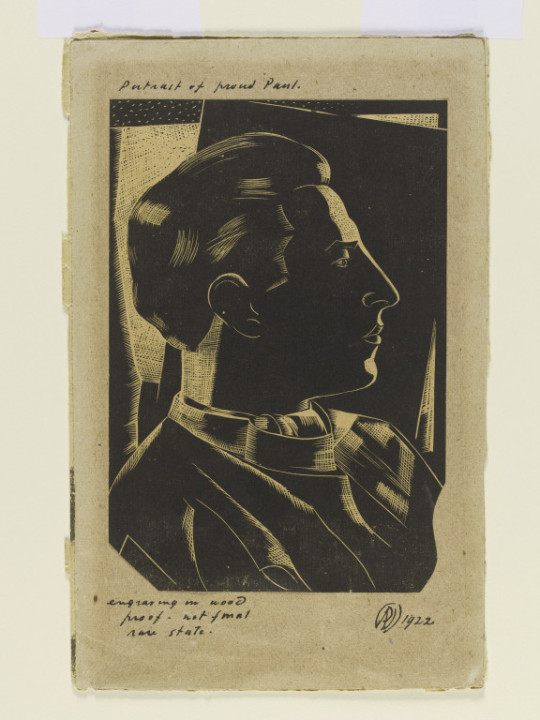

Paul Nash – Self Portrait, 1922