This is the Obituary for Roland Pym by Alan Powers. I post it because he is mostly forgotten now.

Roland Pym, artist: born Cheveley, Cambridgeshire 12 June 1910; died Edenbridge, Kent 12 January 2006.

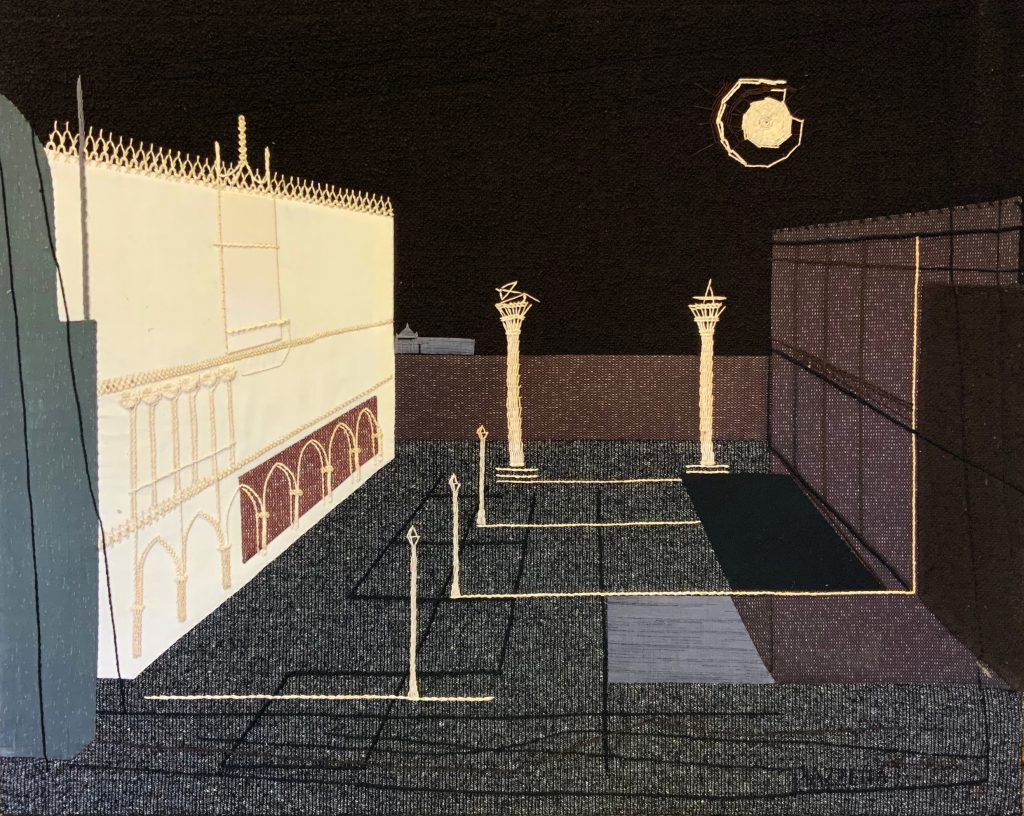

Roland Pym was a painter, illustrator and theatrical designer whose work was redolent of the lyrical and romantic mood of the 1920s and 1930s in England. He had a slight acquaintance with Rex Whistler (five years his senior), and after the Second World War was one of the artists able to supply a similar type of evocative trompe l’oeil decoration. “I suppose Rex Whistler gave me the lead that you could do old things in new ways,” he said in a interview for Country Life in 1999, “but I never consciously imitated him, I would naturally draw like that too.”

Born in 1910 at Banstead Manor, outside Newmarket, Pym moved at the age of four to the family home, Foxwold, near Brasted in Kent, when his father, the future Sir Charles Pym, inherited it. Later he made his home in the nursery wing (lovingly attended by his sister Elizabeth), while his brother, the architect John Pym, occupied the main part of the house.

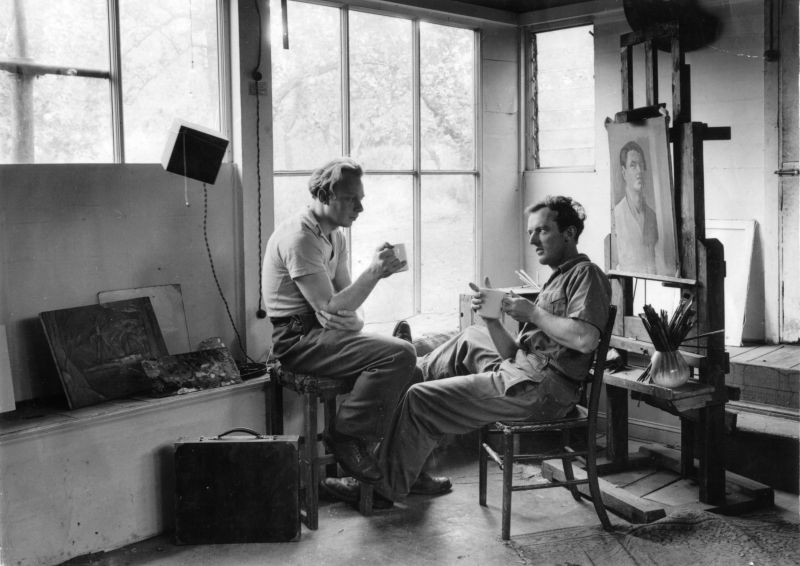

After education at Ludgrove and Eton, he studied at the Slade School and specialised in theatre design, with Osbert Lancaster (two years his senior) as one of his fellow students. Like Lancaster, Pym had an excellent eye for drawing architecture and landscape, but his vision was sweeter, and he peopled his nostalgic landscapes with dashing beaux and doe-eyed belles straight from a Frederick Ashton ballet.

Pym’s mural painting began with a decoration for the Refreshment Room at Lord’s, somewhat in the Doris Zinkeisen manner, won in competition. He painted a bathroom decoration of Victorian Cromer at 39 Cloth Fair, commissioned by the architect Paul Paget for his father, the retired Bishop of Chester.

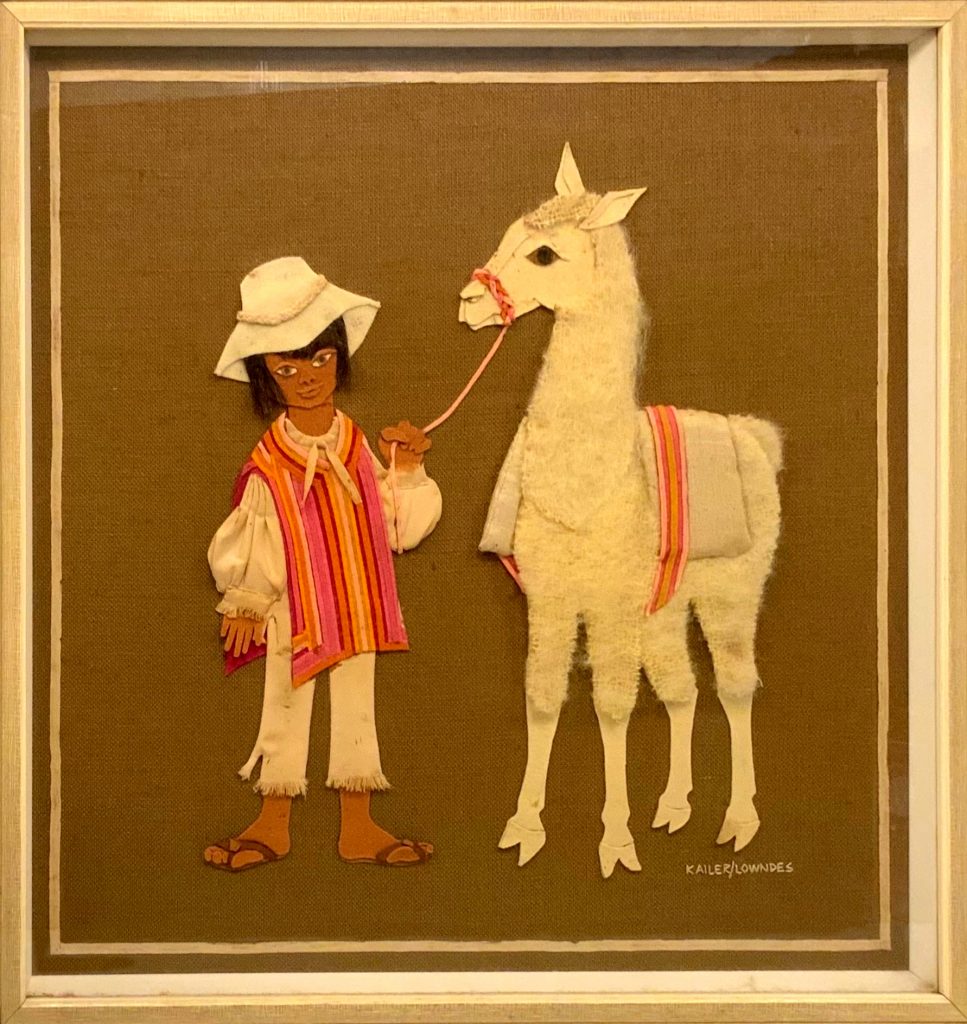

One of his pre-war commissions, for figures in blank windows at Biddesden House, Wiltshire, was the beginning of a long friendship with Bryan Guinness (later Lord Moyne) and members of his family, in England and Ireland, for whom many murals and illustrations were produced down the years – the books including The Story of Johnny and Jemima (1936), The Children in the Desert (1947) and The Story of Catriona and the Grasshopper (1958), all with Bryan Guinness, and, with his daughter Mirabel Guinness, Biddesden Cookery (1987).

During the war, Pym enlisted in the 16th Regiment of the Royal Artillery as a private soldier, and endured some taunting as a fish out of water. However, when he swore back at one of the chefs in the food line, he received a round of applause from the whole canteen. They arrived at Basra in December 1941 and he fought at Tobruk and El Alamein, remaining in the field until 1944. Throughout he kept an illustrated diary, initially in Greek and later in French, for security purposes.

Back in London, he enjoyed his heyday in the theatre, commissioned by Binkie Beaumont of H.M. Tennant to create sets and costumes for ballets and plays, including Oranges and Lemons and Pay the Piper at the Globe Theatre and A Master of the Arts by William Douglas-Home at the Aldwych Theatre. He designed Lohengrin at Covent Garden and Eugene Onegin in Paris.

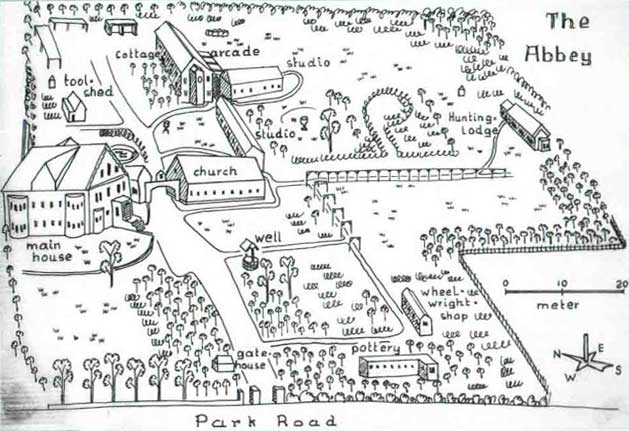

This style of theatre went out of fashion, but Pym could fall back on murals. For the Coronation in 1953, he decorated the Queen’s Retiring Room at Westminster Abbey, and a sequence of domestic commissions, restaurants and hotels followed, with an altarpiece in an icon style at St Mark, Biggin Hill, in 1959. The Saloon at Woburn Abbey, 1971-75, in typical tones of blue and pink, was his largest single work, commissioned after he told the Duke of Bedford, on first encounter, that to paint this room was a life’s ambition. He never retired from murals, and, despite the frailties of age, recently completed a set of four classical figures for Ivry, Lady Freyberg in London.

His greatest achievement as a book illustrator (with a total of 60 books to his name) came late in life when Joe Whitlock Blundell at the Folio Society made the inspired move to commission illustrations for Nancy Mitford’s novels – The Pursuit of Love (1991) was followed by Love in a Cold Climate (1992). Pym did not need to research the Twenties and Thirties settings laboriously, as they were stored in his own excellent visual memory. When stuck for specific details, he could telephone one of the surviving Mitford sisters, and the Duchess of Devonshire commended him on the accurate portrayal of her father as Uncle Matthew, even though he had never met the original. He followed these books with Edith Sitwell’s English Eccentrics (1994) and Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1996).

Pym’s Indian summer continued, with drawing for the parish newsletter at Brasted, edited by his niece’s husband Edwin Taylor, and published in 2004 in book form as The Kentish Scene: pages from the Brasted Diary 1999-2004, with pages from his war diaries and a brief retrospective of other aspects of his work.

Roland Pym never married, although once he came close enough on one occasion for banns to be published. By mutual consent, the relationship ended, however, and he remained wedded to his art and comfortable in his familiar surroundings. As he wrote in The Kentish Scene, “Perhaps it is as beautiful a region as anywhere.”

Alan Powers