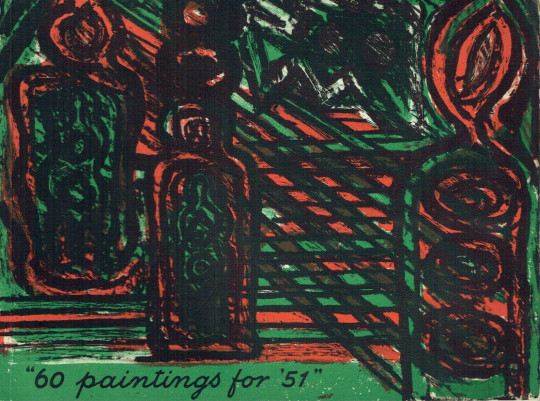

60 Pictures in ‘51 was part of the Festival of Britain celebrations, a touring exhibition of art with 60 paintings by Britain’s leading artists. It came with a booklet but like many books of the time, all the images were in monochrome. I thought it would be entertaining to present the pictures in colour and though I haven’t found all of the paintings, here is what I amassed.

Gerald Wilde cover for the book 60 Paintings for ‘51.

If the Festival of Britain is to achieve its avowed aim of showing the British way of life in all its various facets it is clearly appropriate that a number of our distinguished painters and sculptors should have been given an opportunities to make their contribution.

With this very end in view – and also in the hope of handing down to posterity from our present age something tangible and of permanent value – the Arts Council has commissioned twelve sculptors and invited sixty artists to paint a large work, not less than 45 by 60 inches on a subject of their own choice. †

Keith Vaughan – Interior at Minos, 1950

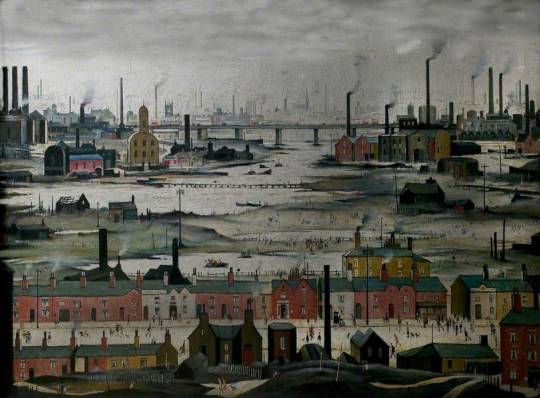

L S Lowry – Industrial Landscape, River Scene, 1950

Lucian Freud – Interior Near Paddington, 1951

Rodrigo Moynihan – Portrait Group, 1951

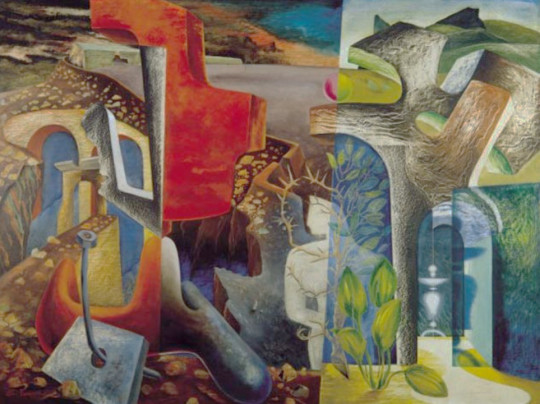

John Tunnard – Return, 1951

Michael Ayrton – The Captive Seven, 1950

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square, London, 1950

John Nash – Afon Creseor, North Wales , 1951

Keith Baynes – Hop-Picking, Rye, 1950

Elinor Bellingham Smith – The Island, 1951

Martin Bloch – Down from Bethesda Quarry, 1951

Edward Burra – Judith and the Holofernes, 1951

Prunella Clough – Lowestoft Harbour, 1951

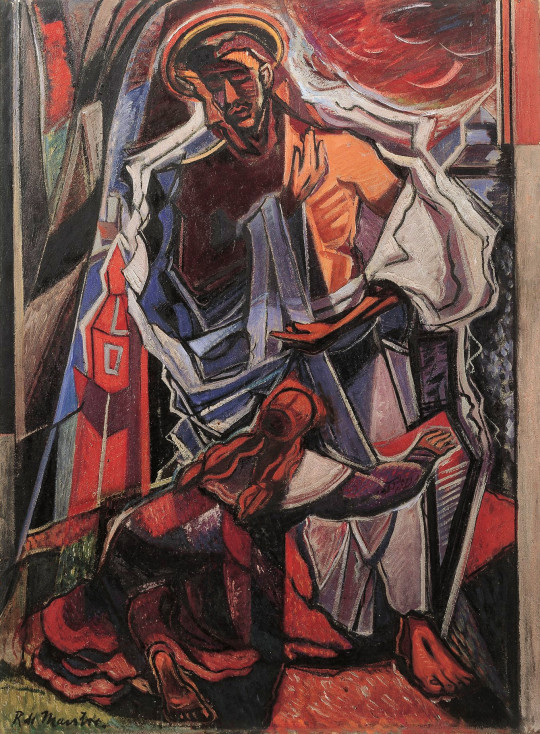

Roy de Maistre, Noli Me Tangere

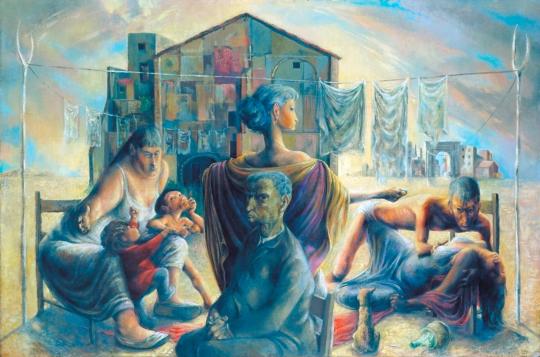

Hans Feibusch, The Prodigal Son

Carel Weight, “As I wend to the Shores…”

Ivon Hitchins, Aquarian Nativity, Child of this Age

Gilbert Spencer, Hebridean Memory

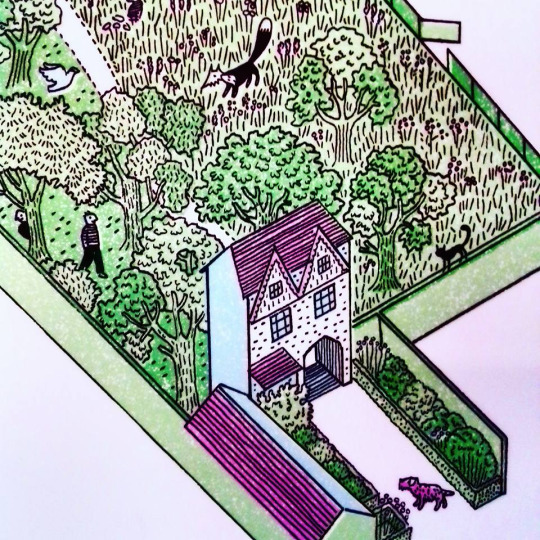

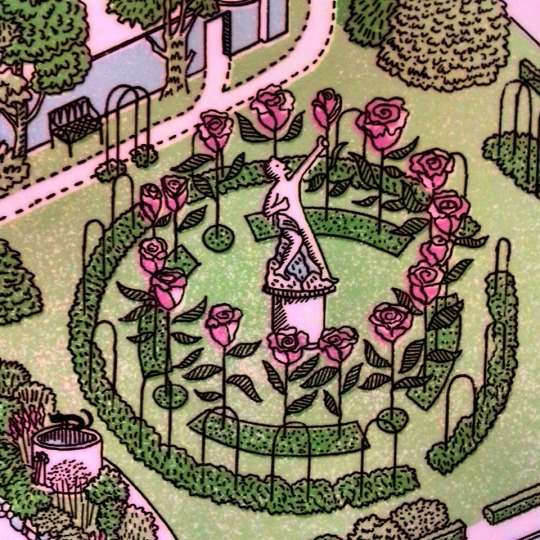

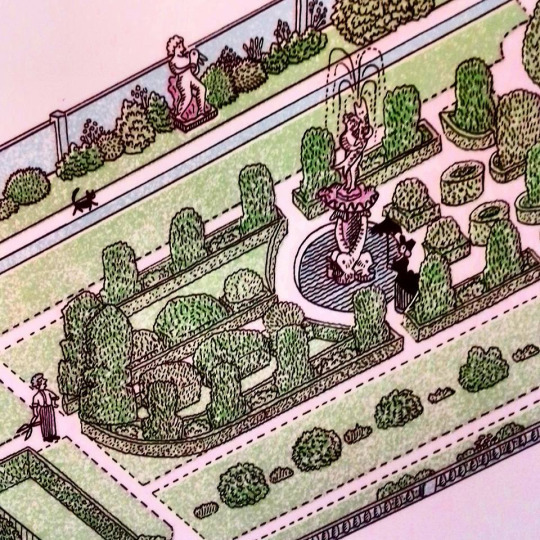

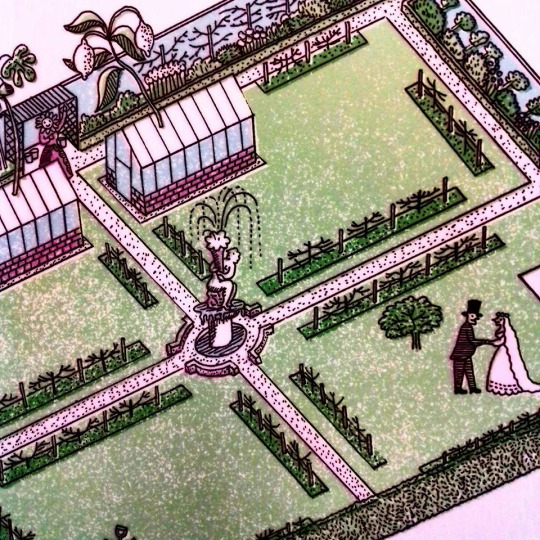

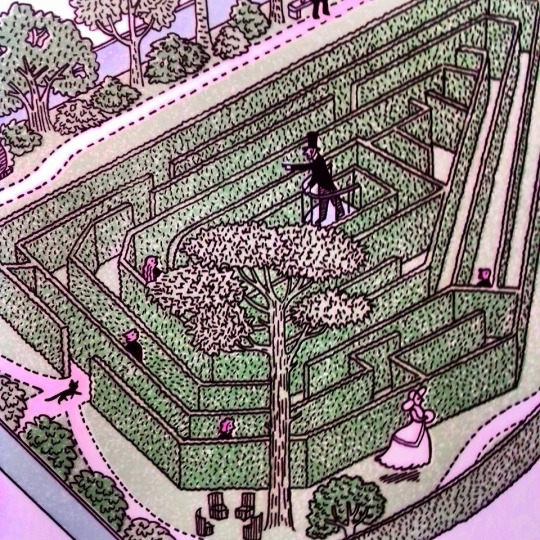

Charles Mahoney – The Garden, 1950

Claude Rogers, Miss Lynne

Ruskin Spear – River in Winter, 1951

Victor Pasmore – The Snowstorm: Spiral Motif in Black and White, 1951

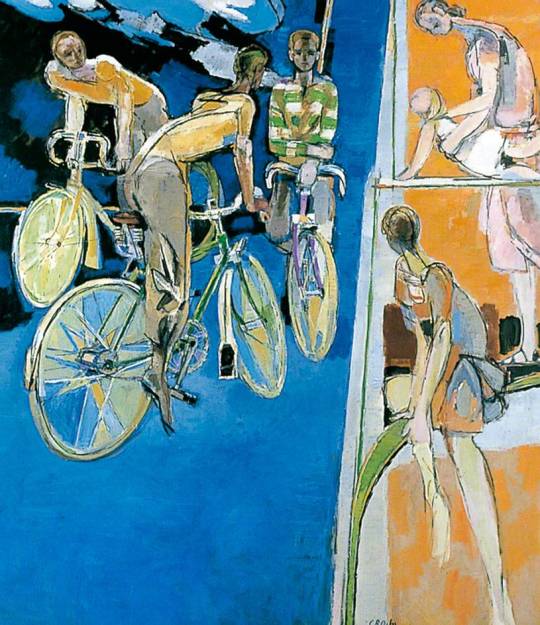

Robert Medley – Cyclists against a Blue Background, 1951

William Gillies – The Studio Table, 1951

Patrick Heron – Christmas Eve, 1951

William Gear – Autumn Landscape, 1950

Peter Lanyon – Porthleven, 1951

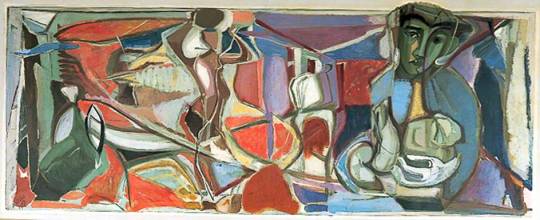

Robert MacBryde – Figure and Still Life, 1951

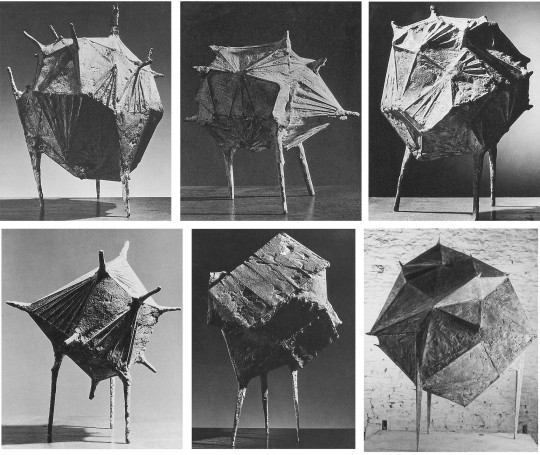

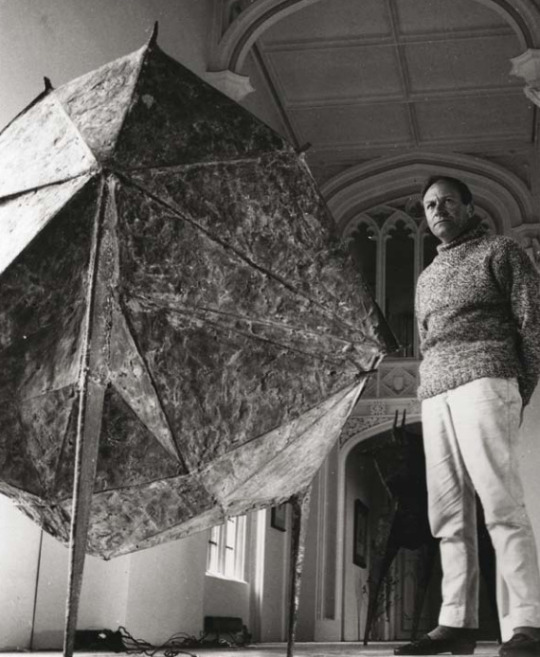

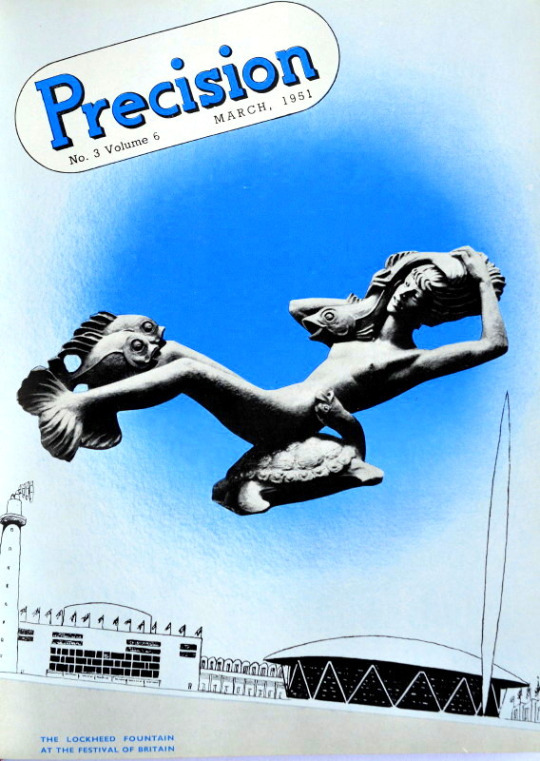

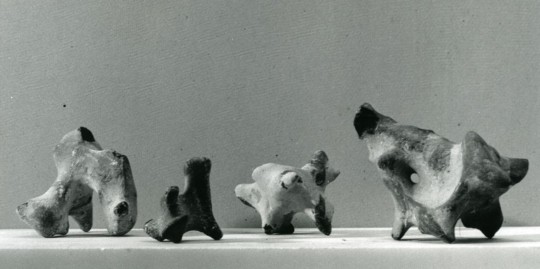

Below are some of the sculptures mentioned in the forward, but these really had their own booklet and part of the Battersea Park Festival Of Britain Pleasure Garden.

Henry Moore – Reclining Figure, 1951

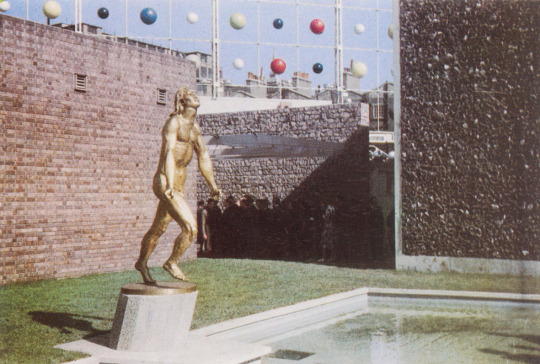

Jacob Epstein – Youth Advances, 1951

Barbara Hepworth

Contrapuntal Forms, 1951

Frank Dobson – Woman and Fish, 1951

The statue above stood in Frank Dobson Square, Tower Hamlets until it was vandalised and she had her head destroyed. Now with scars she sits in Delapre Abbey, Northampton, pictured below.

† Philip James – 60 Paintings for ‘51, 1951