As the title suggests, this is a lecture by Quentin Bell on his family that I haven’t found online, so using a text scanner, I have put it online for you all.

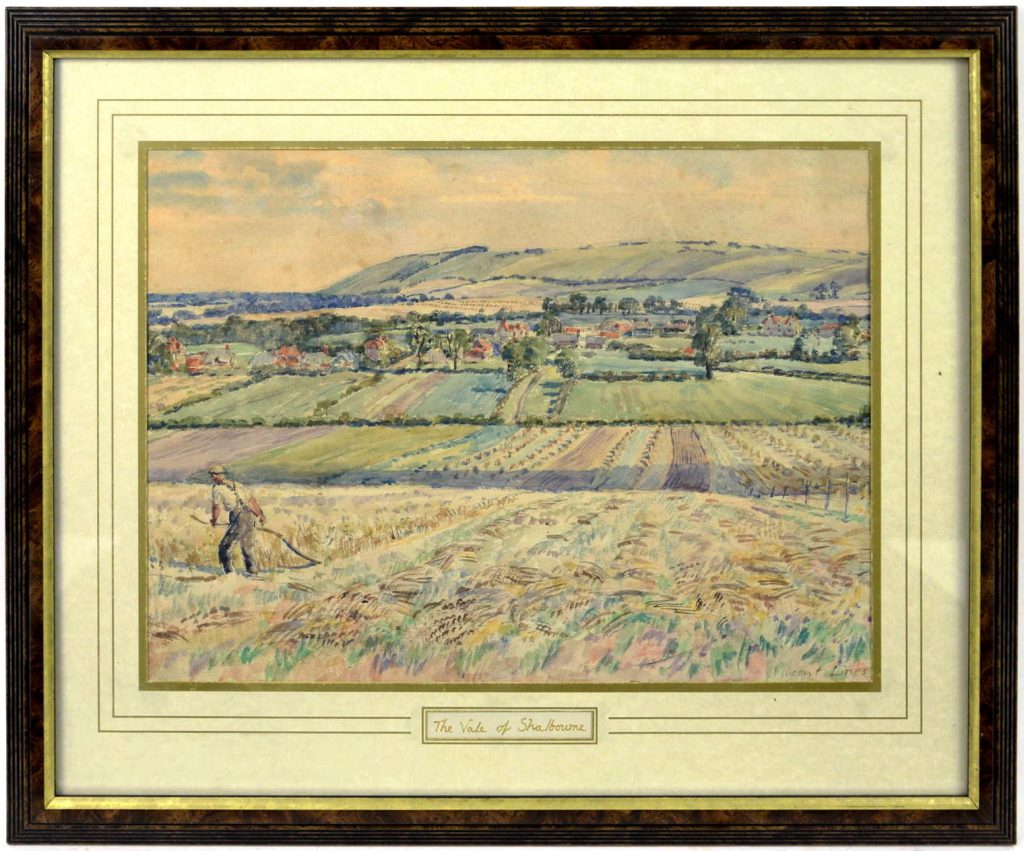

When it was known that the exhibition which you see around you would come to Leeds, Mr. Rowe suggested that I, as the son of the artist, should open it. I resisted this notion. A filial tribute is, of all literary forms, the most difficult and the most perilous censure is out of place and praise

is discounted; impersonality is absurd and intimacy is embarrassing. Thus it appeared, thus it appears to me and I felt that I could not undertake the task. Our Director is, however, a remarkably persuasive and persistent character. When he had twisted my arm very nearly clean out of its socket I agreed to talk, not about my mother, but about the circle of friends to which she belonged, that which the world knows as “Bloomsbury”. I have now become aware that, in accepting this proposition, I made a careful withdrawal from the frying pan into the fire. I shall again be forced into the compromising situation of an advocate; moreover there must be a

certain air of irrelevance about what I say. We are here in a picture gallery and you naturally expect me to talk about pictures, whereas in fact I must talk about writers and politicians, about philosophy and about sex (I shall probably be thrown out before I have done). But here I must ask you to bear with me, the incongruity between that which you see before you

and that which you will hear, is in truth, a part of my argument; it will help me to explain the nature of what they call the ‘Bloomsbury Group’.

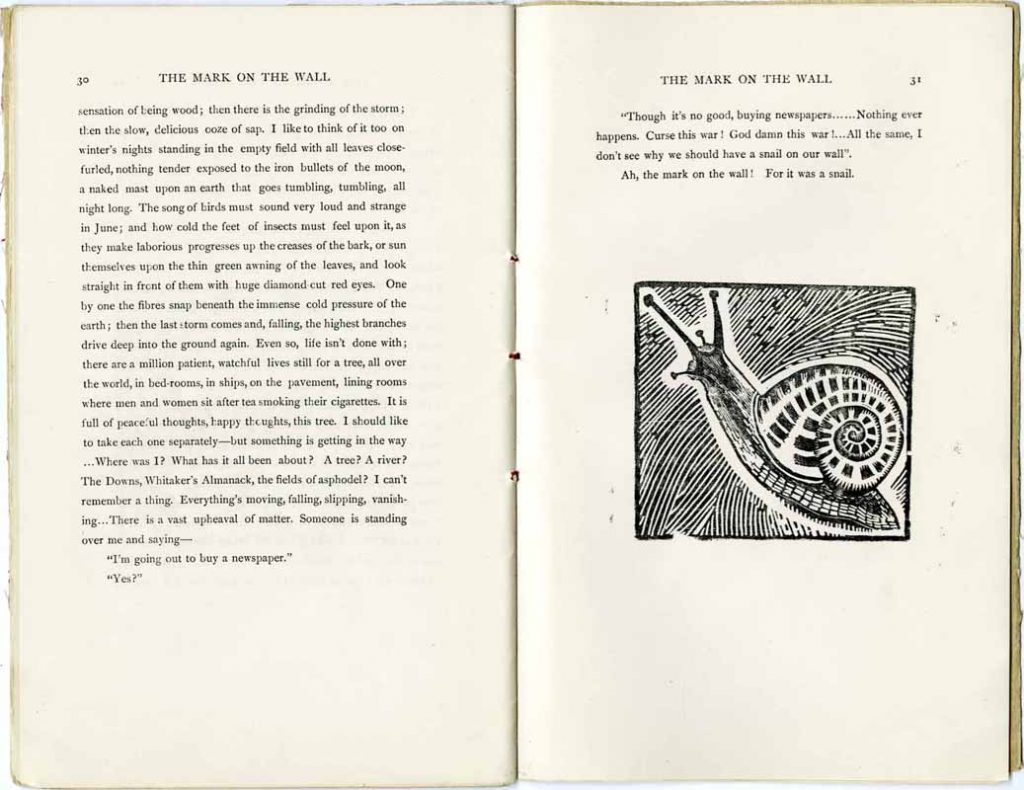

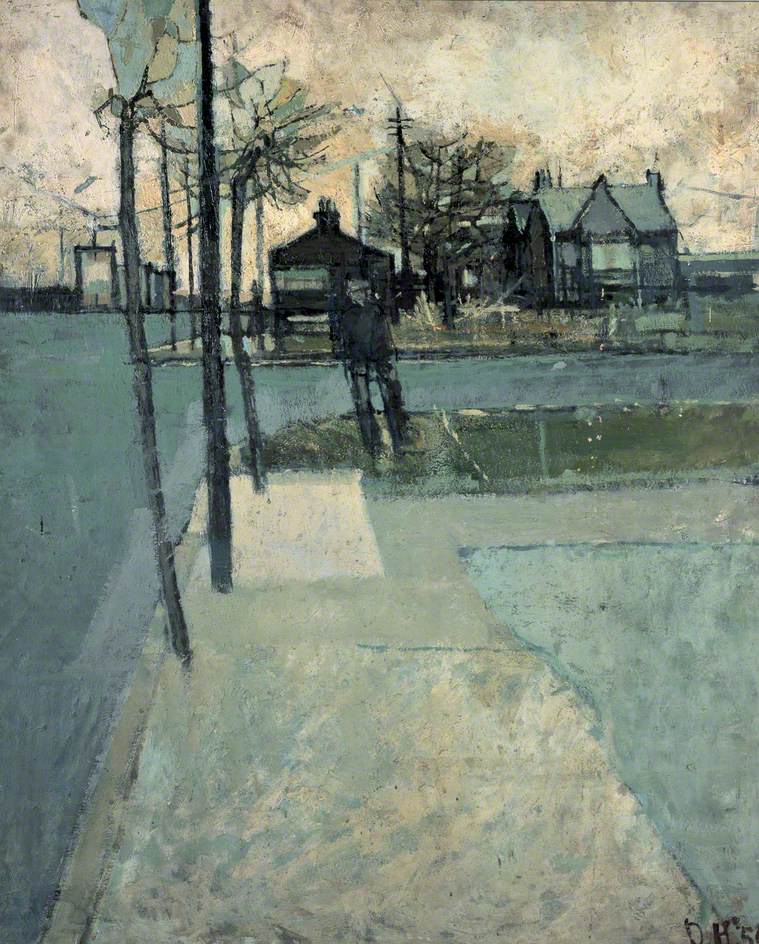

Vanessa Bell – Virginia Woolf, 1912

I shall have to use the word ‘group’, but it is something of a misnomer; when one speaks of ‘a member of the group’ one suggests an organisation with rules, membership cards, and a programme. Bloomsbury had none of these things and it is not at all easy to say who was or who was not within that circle of friends, most of whom lived in Bloomsbury. Circles of friends are not usually perfect circles, in fact they are more like spirals which

extend further and further from their centres in a progressively widening helix. But even this image will not serve, for a spiral departs from a centre and in Bloomsbury there was no centre. I have heard Virginia Woolf described as the ‘Queen of Bloomsbury’ this is pure nonsense; Bloomsbury was never a Monarchy – neither was it a Republic. It was an anarchic entity in so far as it was an entity —without laws or leaders or a common doctrine. The inhabitants themselves differ when it comes to making a list of the so-called members.

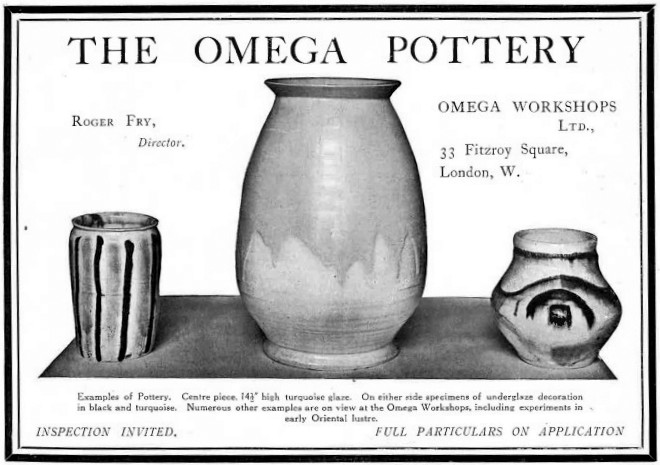

Let me play safe: no account of Bloomsbury could omit Lytton Strachey and his cousin Duncan Grant, the two daughters of Leslie Stephen, Vanessa and Virginia, and their two husbands, Clive Bell and Leonard Woolf; to these we may certainly add Maynard Keynes and Roger Fry.

During the years between 1904 and 1914, these were very closely linked by friendship with Desmond MacCarthy and his wife Molly, Saxon Sidney Turner, Gerald Shove and H. T. J. Norton, E. M. Forster, and, until his early death, Thoby Stephen, the brother of Vanessa and Virginia.

During and after the First World War there were many other close contacts and the list could be enormously widened, but at this period, as I hope to show, the method of classification has to be altered. Now I was born in Bloomsbury and am related to or have been a close friend of all the people whom I have placed on my ‘shortlist’ and some of those in the more

extended catalogue. But I am very far from being an authority on this subject. I was only four years old when the first and most characteristic phase came to an end; and today a great deal has been written on the subject, so that a complete bibliography would, I suppose, be quite an

extensive document. I have read very little but I have read enough to gain the impression that Bloomsbury was, in the opinion of most critics, an unhealthy neighbourhood. Let me quote from one of these critics, Sir john Rothenstein:

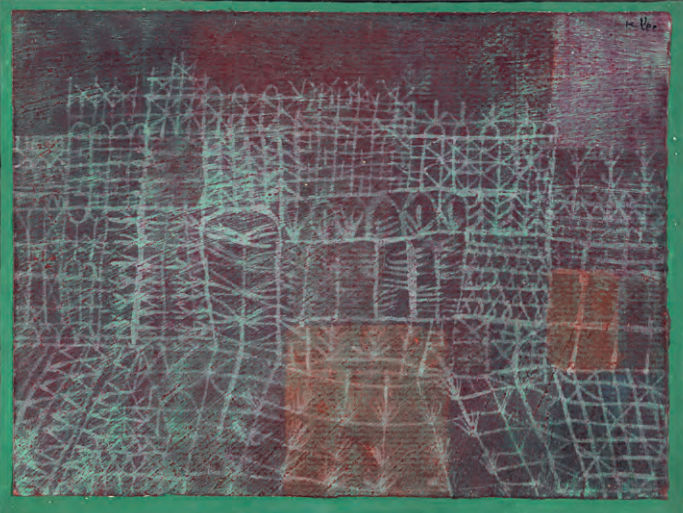

Vanessa Bell – Lytton Strachey, 1911

“I doubt… whether more than a few people are even now aware how closely knit an association ‘Bloomsbury’ was, how untiring its members were in advertising one another’s work and personalities. Most people who came into casual contact with members of this gifted circle recall its charm, its candour, its high intelligence; few…suspected how ruthless and businesslike were their methods. They would have been surprised if they had known of the lengths to which some of these people were prepared to go in order to ruin, utterly, not only the ‘reactionary’ figures whom they publicly denounced, but young painters and writers who showed themselves too independent to come to terms with the canons observed by ‘Bloomsbury’ or, more precisely, with the current ‘party line’…. If such independence was allied to gifts of an order to provoke rivalry, then so much the worse for thc artists. And bad for them it acts, for there was nothing in the way of slander and intrigue to which certain of the ‘Bloomsburys’ were not willing to descend. I rarely knew hatreds pursued with so much malevolence over so many years; against them neither age nor misfortune offered the slightest. protection.”

Rothenstein’s hard words certainly prove how much Bloomsbury has been

disliked. I do not think that they prove very much more than that because,

when it comes to the awkward business of supporting his accusations with evidence, Sir John is completely at a loss. He has in fact been challenged to make good his words and has failed to do so. I understand that in a later edition of his book they have been omitted. But the fabrication, for it certainly is a gross and impertinent fabrication, has been widely circulated and I take this opportunity to deny it.

Now let me turn to a more common and more reasonable line of criticism which is expressed well enough by Mr. A. D. Moody in a study of Virginia Woolf. Mr. Moody describes the origins of Bloomsbury in the Victorian middle class, that section of it which produced the Darwins, the Haldanes, thc Huxleys, the Strachey’s, and the Stephens, academics and civil servants who “became the top layer of the middle class, primarily by virtue of intellectual ability and moral responsibility, though inevitably this later took the form of social exclusiveness.” Mr. Moody sees Bloomsbury as a fraction of this part of the establishment.

“The distinguishing character of the Bloomsbury group derived largely from King’s College, Cambridge, and principally from the philosopher, G. E. Moore, author of ‘Principia Ethica’. The influence of G. E. Moore can be described as a turning back within the ‘intellectual aristocracy in a rather ideal form of Arnold’s ‘Culture’, or rather in that aspect of it which led Eliot to connect Arnold with Pater. The ideal of Moore’s followers was the exclusive and strictly non-practical pursuit of ‘sweetness and light’ ‘love, beauty and truth’ were their own terms. They had the requisite residue of Hebraic conscience, expressed mostly in righteous scorn for the barbarian, philistine and populace, to which all outsiders were consigned; and they subscribed to the Greek heritage. Since their concern was all for a civilisation of the mind, they regarded as outsiders the main body of the Establishment who were concerned with the more practical problems of governing and civilising. Thus they set up a cultural elect within the Establishment elite.”

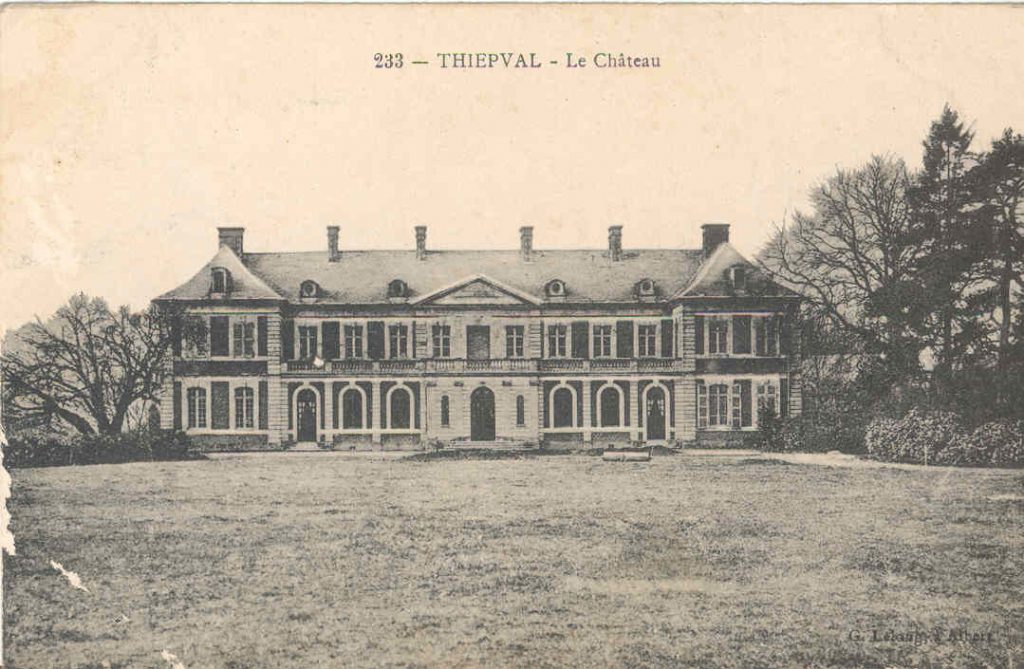

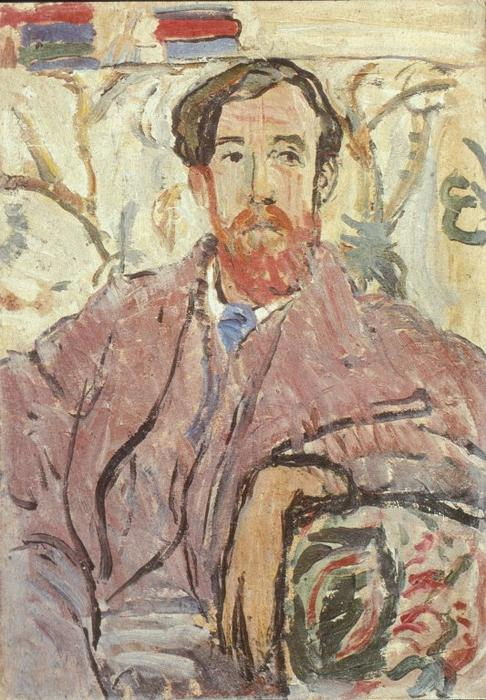

Vanessa Bell – Leonard Woolf, 1940

Mr. Moody overlooks an important element in the formation of Bloomsbury and his generalisations can hardly be applied even to the short list that I have made. I am not quite sure what he means when he says that ‘they subscribed to the Greek heritage’, but certainly the phrase could hardly be used of Roger Fry nor could he be described as a follower of G. F. Moore. But I think that Mr. Moody’s principal criticism, and it is a common one, is that Bloomsbury lived in an ivory tower, that it scorned the populace, and that it disdained the ‘practical problems of governing and civilising’. It is a criticism with which I have some sympathy. I remember that when Maynard Keynes read his essay entitled My Early Beliefs to a group which included what we called ‘Old Bloomsbury’ and also to some much younger persons, we, the young, agreed that it was a fantastically reactionary document and revealed a politically innocent and parochial attitude on the part of Cambridge at the beginning of the century which we deplored. Nevertheless, whether their political beliefs were right or wrong, we could hardly maintain that our elders had withdrawn from political action. Neither Maynard Keynes, Leonard Woolf nor Lytton Strachey could be described as being indifferent to the practical problems of governing and civilising; Keynes and Woolf were in fact public servants. The suffrage movement, the foreign and colonial policy of the Labour Party, the credit structure of the Western world have all felt their influence.

The third critic whom I would like to mention was D. H. Lawrence.

Lawrence went to Cambridge in 1915 and met a number of people, some of whom Keynes, Duncan Grant and, perhaps, Francis Birrell, the son of Augustine Birrell may fairly be described as ‘members of Bloomsbury’, others, such a Bertrand Russell, who can not. His reaction was sharp and decisive:

“…to hear these young people talk really fills me with black fury: they talk endlessly, but endlessly and never, never a good thing said. They are cased each in a hard little shell of his own and out of this they talk words. There is never for one second any outgoing or feeling and no reverence, not a crumb or grain of reverence. I cannot stand it. I will not have people like this….”

And to David Garnett who had brought about this unlucky meeting:

“Never bring Birrell to see me any more. There is something nasty about him like black beetles. He is horrible and unclean. I feel I should go mad when I think of your set, Duncan Grant and Keynes and Birrell. It makes me dream of beetles….”

Keynes, in the work to which I have already alluded, considers Lawrence ignorant, jealous, irritable and hostile (and, as one who remembers the charm, sincerity and good humour of Birrell, I should add: blind), but he goes on to ask whether there was not “something true and right in what Lawrence felt? There generally was. His reactions were incomplete and unfair, but they were not usually baseless.” In a brilliant analysis of the influence of Moore on Cambridge and of the way in which the profoundly unworldly teachings of that philosopher changed in the hands of a generation which found that it could not accept the high seriousness or the

austerity of its starting point, Keynes concludes that Lawrence was not altogether wrong. The criticism may be just, but is it a criticism of Bloomsbury? Could it be directly applied to, shall we say, Roger Fry

or Virginia Woolf’? I doubt it. Is there in fact enough community of thought and feeling in Bloomsbury to make any criticism of this kind valid?

I think that perhaps there is, that the quality which Lawrence called ‘irreverence common to all; but one cannot understand Bloomsbury unless one begins by acknowledging its heterogeneous character and observing that it was heterogeneous in a very special way. It is because this has not been understood that so many of the criticisms that are aimed at it fall partly or wholly outside the target area. I think I may come at the nature of

Bloomsbury by looking at its origins. In so doing I must again admit that I do not speak as an authority, in fact I rely very largely upon a volume which Sir Leslie Stephen wrote for his children after his wife’s death. It gives a sufficiently vivid picture of one of the families from which Bloomsbury sprang but it is, of course, concerned only with this one family. I will try, however, to confine myself to those transactions which were reasonably typical of many such families and which set the

tone for Cambridge and for London at the end of the Victorian Age.

What kind of people were they? They had money, not enough to keep them in idleness but enough to enable them to choose the kind of work that they would do in the world. They went into the Universities, into the Civil Service —-above all into the Indian Civil Service—they wrote books, they edited journals. The great intellectual adventure of their lives was

the struggle between faith and reason. The struggle was an arduous one and certainly it would be a mistake to think of our grandfathers as living a sheltered life—it was the very opposite for they looked out with dismay into an empty universe. But it was a private struggle. By this I mean that, unlike continental atheists, English freethinkers were not naturally drawn to a political position and that, although they had changed their views

concerning the origin and destiny of men and women, this in no way altered their views concerning the proper relationship between ladies and gentlemen. The enlightened English home at the end of the century might be, and very often was, a benevolent despotism; but it was and it remained despotic. Our Father in heaven might be removed to the world of myth,

but our father at the breakfast table persisted. Just what this could mean in practice in what was, taking one thing with another, a happy family, we may see from Virginia Woolf’s portrait of Mr. Ramsay in To the Lighthouse. Stephen worshipped his wife;

“He desired,” writes Noel Annan, “to transform her into an apotheosis

of motherhood, but treated her in the home as someone who should

be at his beck and call, support him in every emotional crisis, order the

minutiae of his life and then submit to his criticism in those household

matters of which she was mistress… he was for ever trampling upon her feelings, wounding the person who comforted him, half conscious of his hebetude, unable to contain it.”

This was the paternalist structure of society in action as the Stephen children saw it and they did not have to look very far afield in order to see how the conventional morality in which they had been reared could turn to unreasoning savagery. A short entry in my grandfather’ private memoir reads thus:

“There happened a terrible scandal in consequence of which Lady

Somers daughter, Lady Henry Somerset, was separated from her husband —a blackguard.”

Behind this brief statement lies a Victorian tragedy. My grandmother’s

cousin had married a man who, in so far as he was unfaithful to her, might fairly be termed ‘a blackguard’, but the terribly scandalous nature of his ‘blackguard’, but the terribly ‘blackguardism’ lay in the fact that his partner in sin was of his own sex.

Now observe the workings of Victorian morality: when the scandal broke, and it was the young wife’s mother who made it public, the censure of society was brought to bear, not on the husband, who escaped to Italy and ended his days in cultured ease, but upon the wife. Her guilt consisted in the fact that she reminded society of something that it preferred to disregard. She was cut, ignored and as far as possible forgotten by good society. I am happy to say that my grandparents proved on this occasion that they were not really members of good society. I do not think it will be denied that, with very few exceptions, the hard thinking, bravely speculative intellectual elite when confronted with that which it considered ‘morbid’ or ‘unnatural’ was, like the rest of good society, bereft of courage, humour, compassion and reason.

The younger generation was confronted, then, by a system of morality which was by no means purely ethical, it was a system which allowed the strong and the fortunate to injure the weak, the herd to dominate and destroy the individual. This, it may be objected, is still the case but today audible protests are made, eighty years ago they were not. G. E. Moore did not offer an escape from this system, as Keynes has pointed out ‘he found a place in his religion for vindictive punishment’ and no place at all one may add for l’homme moyen sensuel. But his disciples could find in his concern with passionate states of contemplation and communion, with love and with beauty, enough to write into his teachings a doctrine of complete nonconformity in faith and morals. It is interesting to notice that Bertrand Russell came to the same position via Spinoza. The a priori moral judgment, unquestioned acceptance of established patterns of behaviour, the taboo that forbids further discussion of a subject, all were discarded and the burden of making ethical decisions was taken from society and thrust upon the individual. This I think was characteristic of Bloomsbury

at the beginning of the century. I think it had a deep effect upon the habits

of speech and thought of the group and that its influence is discernible in the writings of Lytton Strachey, E. M. Forster, Virginia Woolf and even of

Roger Fry.

This then brings me to the first common characteristic of the group, its readiness to talk about anything:

“They showed a taste for discussion in pursuit of truth and a contempt for conventional ways of thinking and feeling contempt for conventional morals, if you will” says Clive Bell and adds:

“Does it not strike you that as much could be said of many collections of young and youngish people in many ages and many lands? For my part, I find nothing distinctive here.”

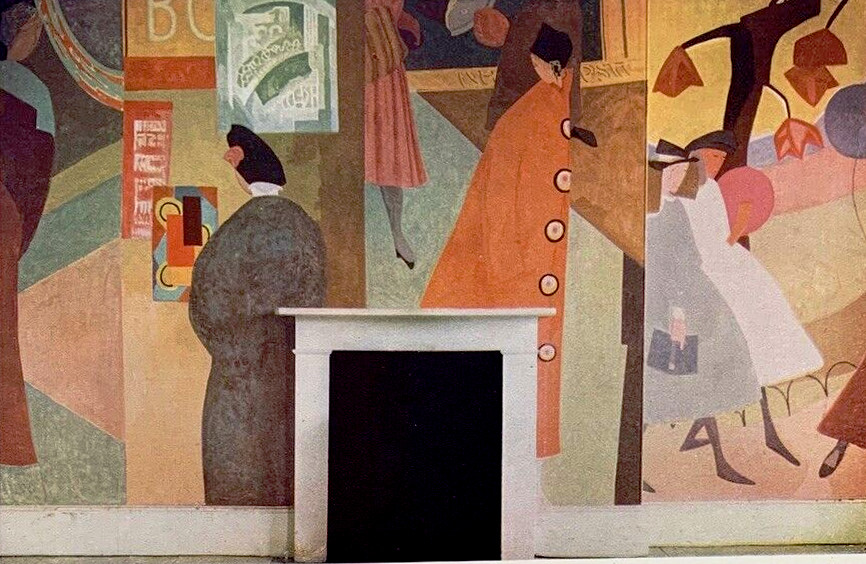

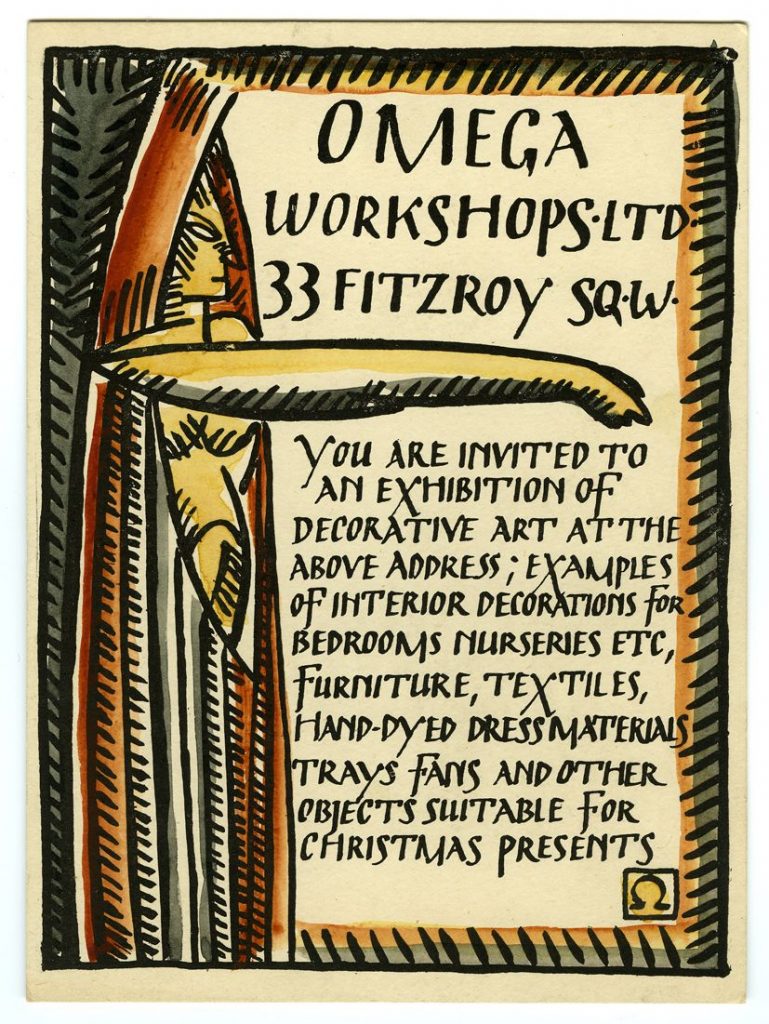

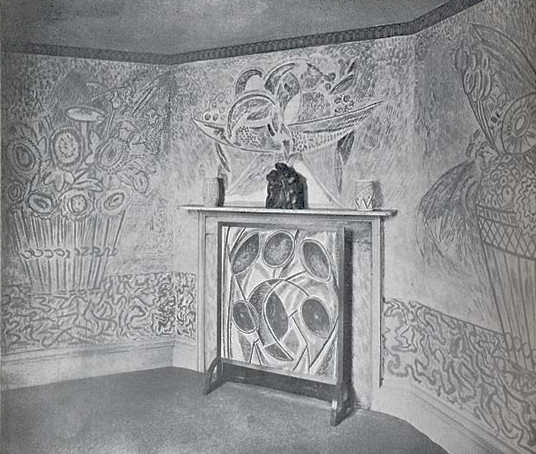

Personally I doubt whether any group had ever been quite so radical in its approach to sexual taboos. I am not sure. But I am sure that in this country, at all events, there had never before been a moral adventure of this kind in which women were on a completely equal footing with men with, so to speak, no holds barred. It was this which, after 1903 at all events, made Bloomsbury very unlike any other Cambridge group, made it in fact ‘un-Cambridge’. But there was something else, something even more important, an influence which was in a sense anti-Cambridge, and this I think has been overlooked by most of the people who have written about Bloomsbury. It is here that I would ask you to look at the pictures on the walls. You will search in vain I think for the influence of G. F. Moore or Bertrand Russell, you will find that of Cezanne and Matisse, of Velasquez and of Duncan Grant. Vanessa and Virginia Stephen were from the first. affected by two parental influences. From their father they imbibed and reacted against a purely Cambridge doctrine, the doctrine of men such as Fav cett and Maitland, which was concerned entirely with the world of literature and of ideas. From their mother they learnt of a very different society, the society of Little Holland House, of Watts and Woolmer, Val Prinsep and Burne Jones. They reacted against this too, in so far as it represented the late Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, but their reaction was an aesthetic reaction. Leslie Stephen climbed the Alps, at his feet lay Milan and Sta. Maria delle Grazie, Turin and Bergamo. But never, in all his life, did he go down to visit these cities of the plain. For him Paris was a station between London and Geneva, the fine arts a mystery that he did not care

to examine. His children did not climb the Alps, they hastened past them to Arezzo and to Padua; above all they journeyed to Paris and there, with Clive Bell, Duncan Grant and Roger Fry, established friendships with Picasso, Derain, Andre Marchand, Segonzac and Matisse such as have seldom existed between artists on opposite sides of the Channel.

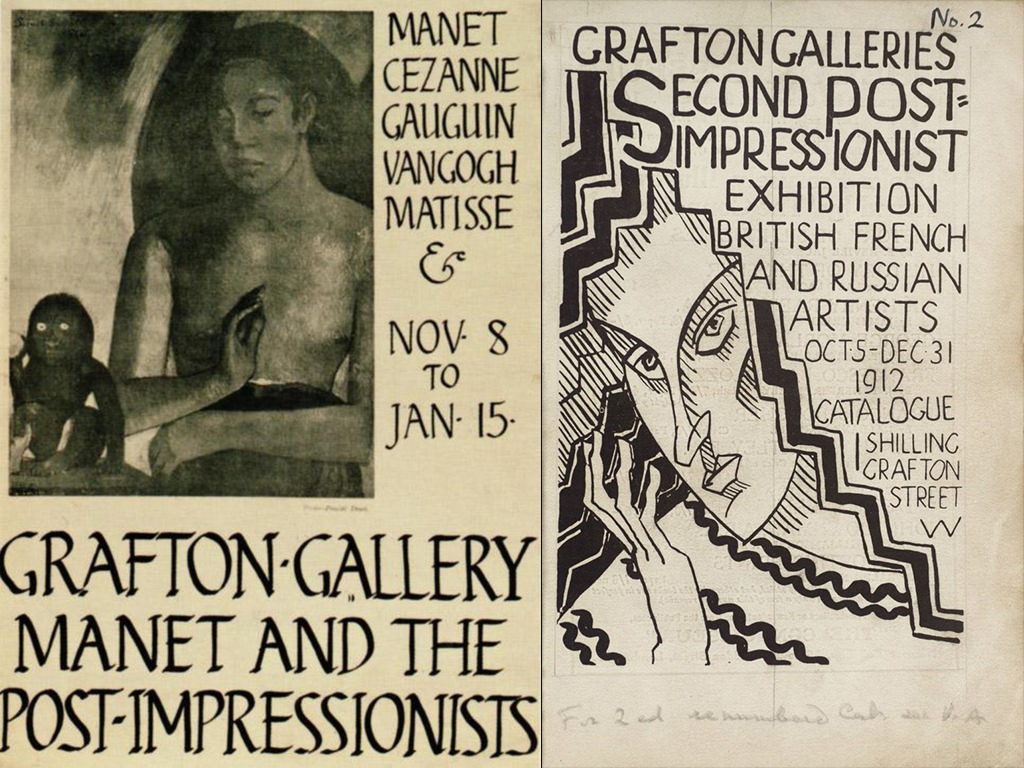

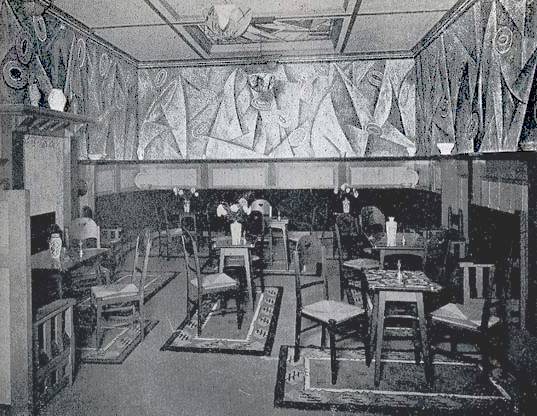

The great and moving spirit in all this was Roger Fry and, to my mind, the

great and decisive act of Bloomsbury was the Post Impressionist exhibition of 1910. The exhibition itself represented comparatively little to those of the group who were neither artists nor art critics. But the reaction to the exhibition was important. Desmond MacCarthy, who was secretary of the first exhibition, has left his account of the laughter and abuse with which it was greeted. Leonard Woolf has recently published his account of the

second exhibition —in 1912.

“The first room was filled with Cezanne watercolors. The highlights in the second room were two enormous pictures of more than life-size figures by Matisse and three or four Picassos. There was also a Bonnard, and a good picture by Marchand. Large numbers of people came to the exhibition and nine out of ten of them either roared with laughter at the pictures or were enraged by them…. The whole business gave me a lamentable view of human nature, its rank stupidity and uncharitableness… hardly any of them made the slightest attempt to look at, let alone understand the pictures and the same inane remarks were repeated to me all day long. And every now and then some well-groomed, redfaced gentlemen, oozing the undercut of the best beef and the most succulent of chops, carrying his top hat and grey suede gloves, would come up to the table and abuse the pictures and me with the greatest rudeness.”

The intensely individualist revolt against Victorian morality is paralleled by the equally individualist revolt against Victorian aesthetics. In both cases Bloomsbury is on the side of the individual and against what it sees as the irrational power of the establishment. In both cases it stands on the side of reason and tolerance and against authority. Such an affirmation of individualism implies, in the absence of any alternative system of ethics and belief, irreverence. And I think that Lawrence was right when he found Bloomsbury lacking in that quality. I think also that critics of Bloomsbury are right when they accuse it of a centripetal, a clannish tendency, although here, if one is to be fair, it is necessary to make

all kinds of reservations and qualifications. To some extent the mere fact that Bloomsbury was committed to an attitude which was fiercely resented by the majority of ‘right-thinking people’ made it more compact. The experience of the two post-Impressionist exhibitions augmented that

feeling; but the really formative moment, in this respect, was the war, that war which was humorously styled ‘the war to end war’.

Here again the reactions of Bloomsbury were not uniform, some opposed the war and became conscientious objectors, others joined in the war effort. But there was, I think, a common reaction to the communal spirit of that time, a spirit of unreasoning devotion to the Fatherland and equally unreasoning hatred of the enemy. My generation has seen a war which was, in all conscience, horrible enough and in many ways more terrible than that which preceded it; but at least it was not obviously and hopelessly futile, the generals could at least lead armies and win victories. From December 1914 to March 1918 the pointless and gigantic butchery was organised by elderly gentlemen who remained at a safe distance from the firing line, in order that the business —and it was a profitable business —might continue. The press, the publicists and the politicians had continually to proclaim the unspeakable wickedness of the enemy, the purity of our intentions, the stirring integrity of our allies, and the fact that we were in some mysterious, imperceptible and yet indubitable fashion, winning. It was this the hatred and the hubris of the home front that Bloomsbury refused to accept, it was here that it proved its final and complete irreverence for anything save the intellect. Lytton Strachey ordering a glass of lager beer in a restaurant found himself faced by the protests of his neighbour, protests which ended with the half apologetic admission, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, but it drives me silly with rage to see a Britisher drinking a hun beer.” “So I observe,” replied Strachey. The refusal of the intellectual to be stampeded by a collective emotion whether it be of love or of hatred, is exasperating to the ordinary man and calls forth all his witch hunting instincts; but it is even more exasperating to the intellectual who has accepted the collective emotion. There is, I think, no more touching record of D. H. Lawrence than his letter to Ottoline Morrell of 14th May, 1915, after the sinking of the Lusitania: There had been riots in London, German shops or at least shops with German names, were smashed and looted and Lawrence wrote:

“I cannot bear it much longer, to let the madness get stronger and stronger possession. Soon we in England shall go fully mad, with hate. I too hate the Germans so much, I could kill every one of them. Why should they goad us to this frenzy of hatred, why should we be tortured to bloody madness, when we are only grieved in our souls, and heavy? They will drive our heaviness and our grief away in a fury of rage. And we don’t want to be worked up into this fury, this destructive madness of rage. Yet we must, we are goaded on and on. I am mad with rage myself. I would like to kill a million Germans —two millions….”

and then at the end of the letter:

“Don’t take any notice of my extravagant talk -one must say something.”

If one is D. H. Lawrence one must, even if one knows at bottom that what one is saying is stupid and odious, for it is produced by a real sentiment of anger and of affection, real sentiments are holy things, things to be treated with reverence. It is not surprising that Lawrence detested Bloomsbury, nor is it surprising that under the stress of war Bloomsbury became increasingly separated from the main current of intellectual life, for it was the liberals the progressively minded people who were loudest in their rage against the Germans and who, unlike Lawrence, mistook their emotions for patriotism and sanity. Apart from religious and political extremists, Bloomsbury had no allies. Bloomsbury, according to Vanessa Bell, ended in 1915. In a sense it is true and yet the achievements of Bloomsbury were

still to come. It was the war itself which, more than anything, brought Leonard Woolf into practical politics; it was Versailles which impelled Keynes to make his celebrated attack upon a peace which he saw as vindictive and unworkable. Eminent Victorians was, I think, published

in the same year. By the mid nineteen twenties, the communal feeling that had made the war and made the treaty was dissipated, people began to wonder whether there might not, after all, be something to be said for reason and critical detachment. At the same time the war itself shook the patriarchal morality of the nineteenth century to its foundations. The libertarian spirit of Bloomsbury was no longer exceptional, neither was it any longer so odd a thing to admire Cezanne or even Picasso. A new generation arose which has sometimes been identified with Bloomsbury but for which I think that one ought to find another name, even though the older members were often very intimate with their younger contemporaries. Bloomsbury had ended by the twenties in the sense that its always very tenuous common qualities ceased to be meaningful; its beliefs were shared by many people and as the individuals who had originally made it developed, they became less and less capable of being contained within any generalisation. A group of friends continued to meet, held together by old affections and, perhaps, by the memory of a time when they had been unified in moral isolation; but by the 1930’s it was no longer possible to find any intellectual attitude that would distinguish them from their fellows. Thereafter the group itself rapidly changed character as it fell beneath the sentence of the President of the Immortals.