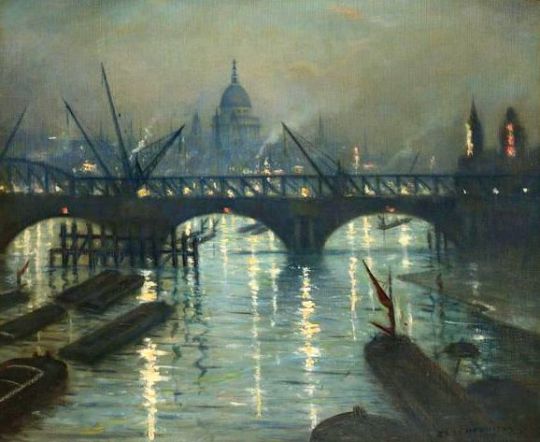

Nov ‒ Dec 1915. Goupil Gallery, London

I thought this review of the London Group Show was of note as it features so many wonderful painters. I have found some of the paintings on show to illustrate it. Originally published in the magazine, Colour, 1915.

Harold Gilman – Leeds Market, 1913

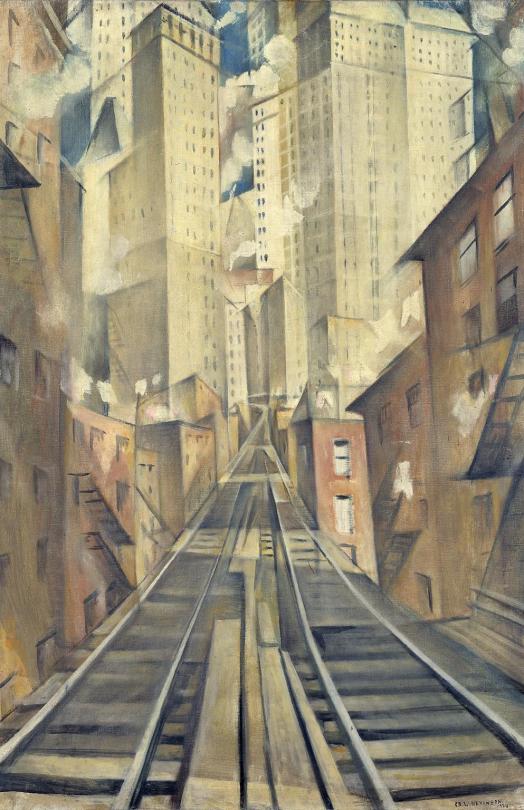

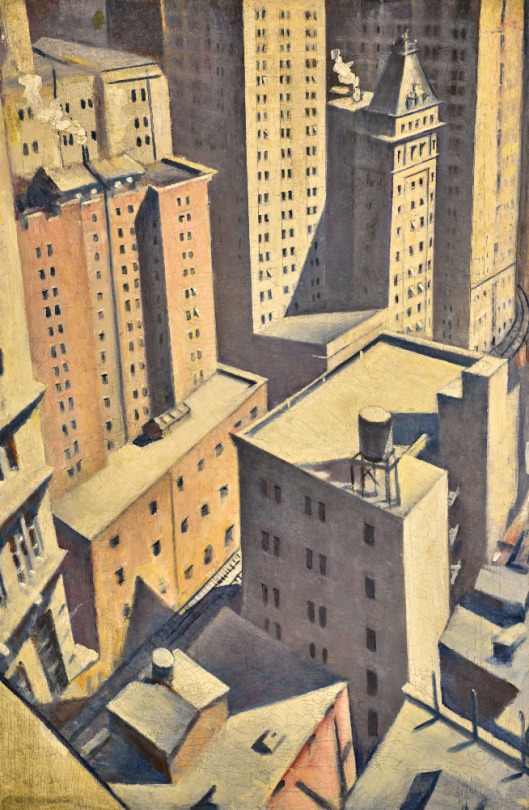

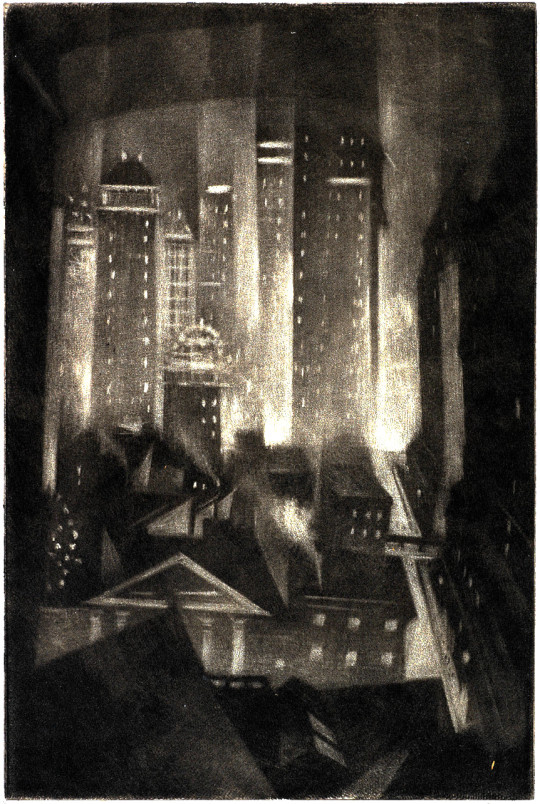

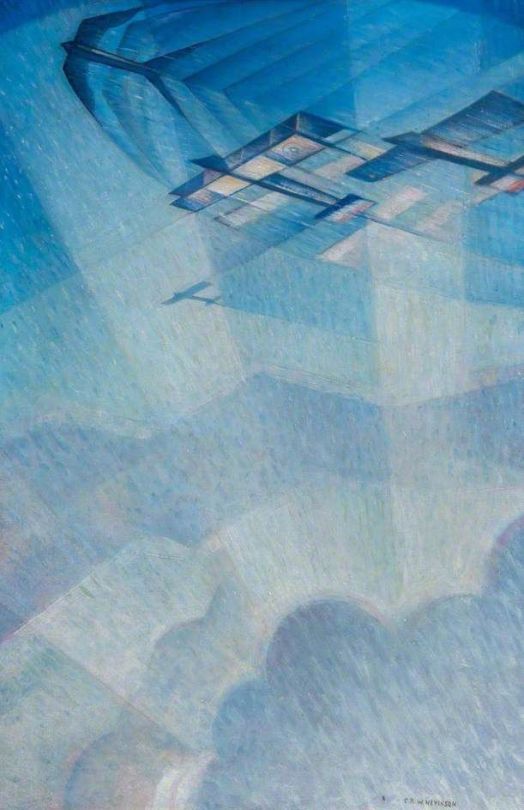

London Group – The third Exhibition of this group is now on exhibition at the Goupil Salon is one of in which a certain sense of gaiety and experiment is to be seen. The spirit of adventure is also alive, and the group being one where members are not subject to the tyranny of a selecting committee, one notices that with a free hand these artists can give liberal expression to their point of view. There is much good painting in various Styles, and Little that is bad add, while a high level of excellence is in evidence throughout the show. W. B. Adeney show several canvases in which the design is obviously the first aim of the artist. In most cases he is successful. Thérèse Lessore is also greatly interested in the designing of her canvases, but colour also plays an important part. Harmonies of Pale colours, that always good colours, together with a simplified rendering of the figures which people her canvases, make for a series of distinguished works. As decorations they are complete.

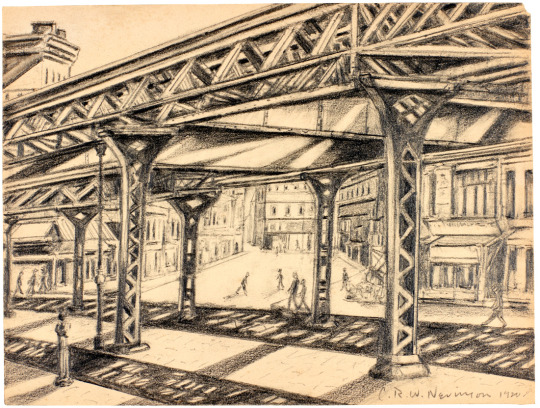

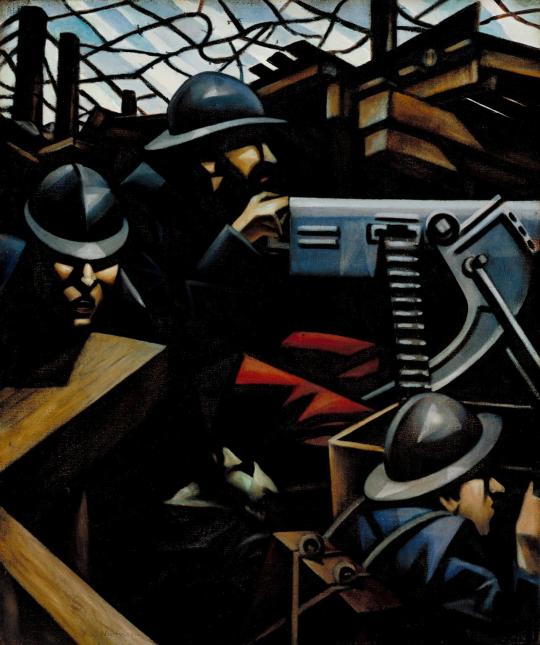

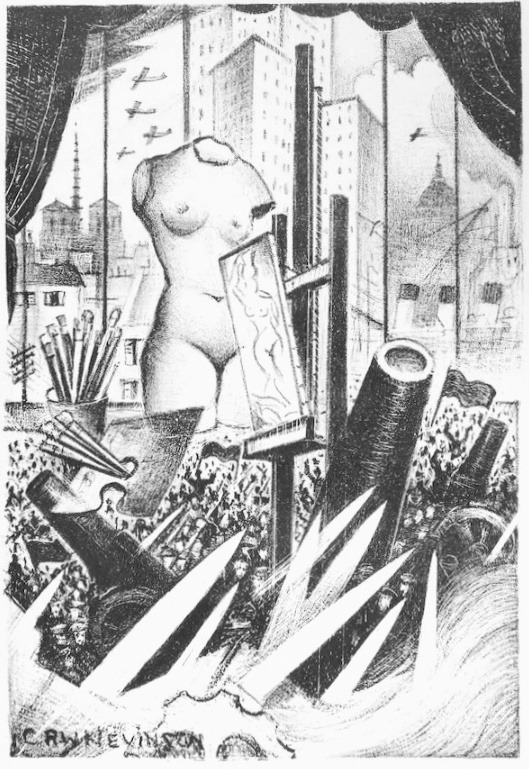

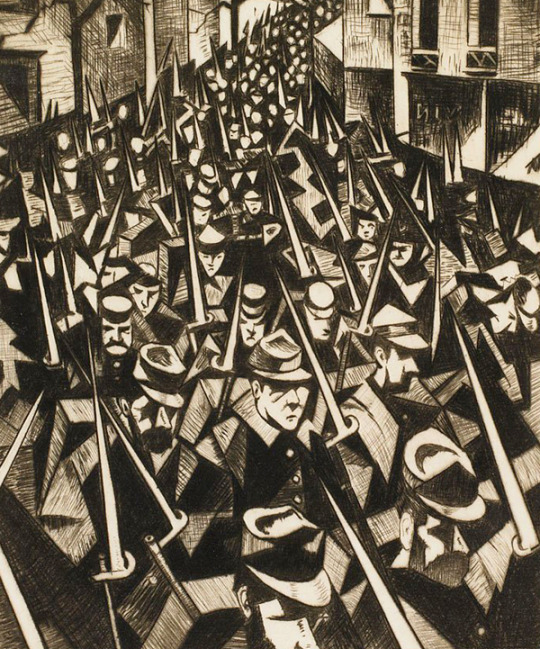

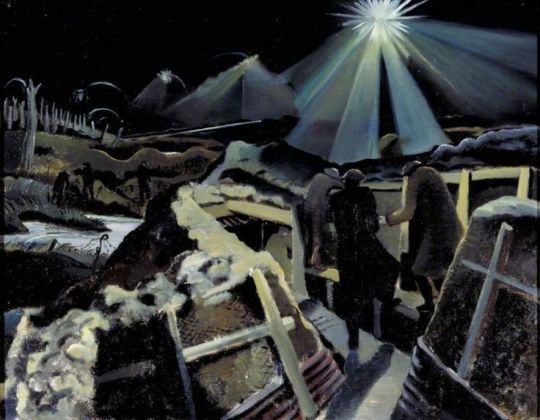

Christopher R. W. Nevinson – Les Guerre de Trous, 1914

Figure work and portraits at this exhibition are few, and of the latter nana satisfactory. Of the former, Thérèse Lessore, who we have already mentioned, Mary Godwin, and Horace Brodzky, contribute. The last mentioned painter shows a decoration in which three nudes energetically struggle with a large stone. This work is evidently a sketch for a mural decoration to be painted on a large scale. Mary Godwin’s subjects display a searching after luminosity and texture.

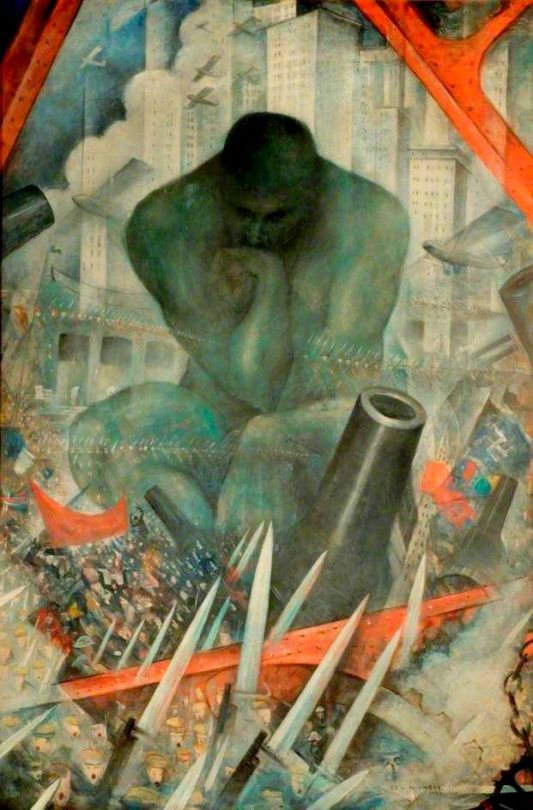

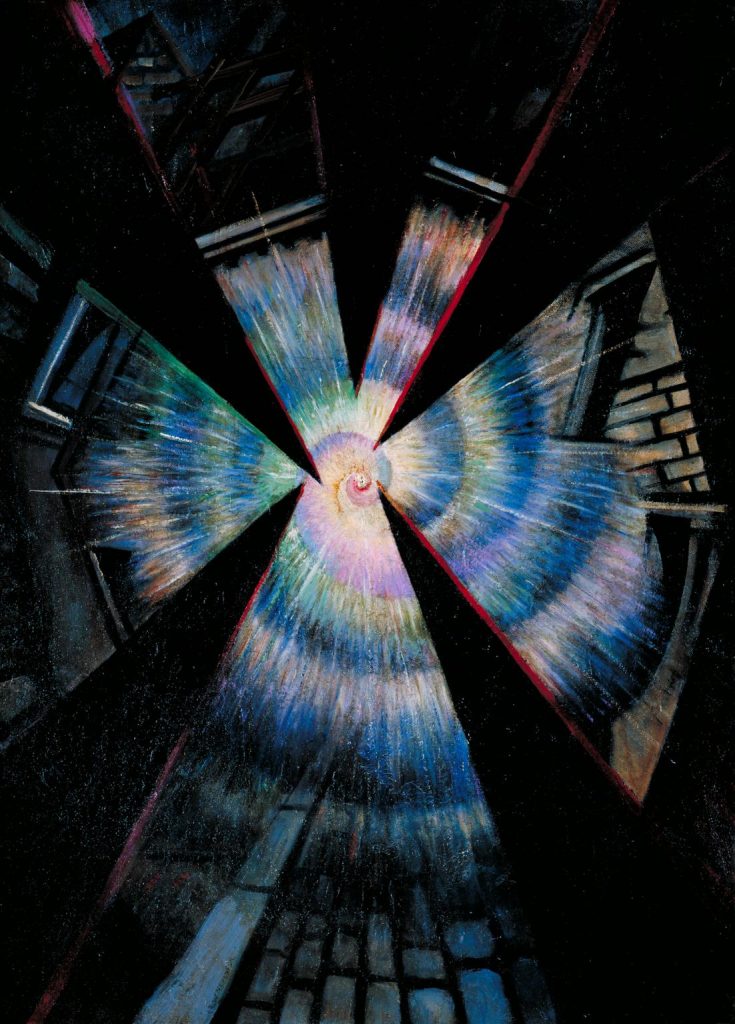

Mark Gertler – Creation of Eve

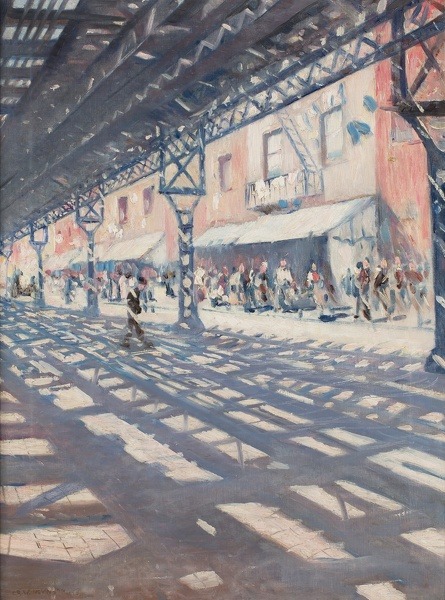

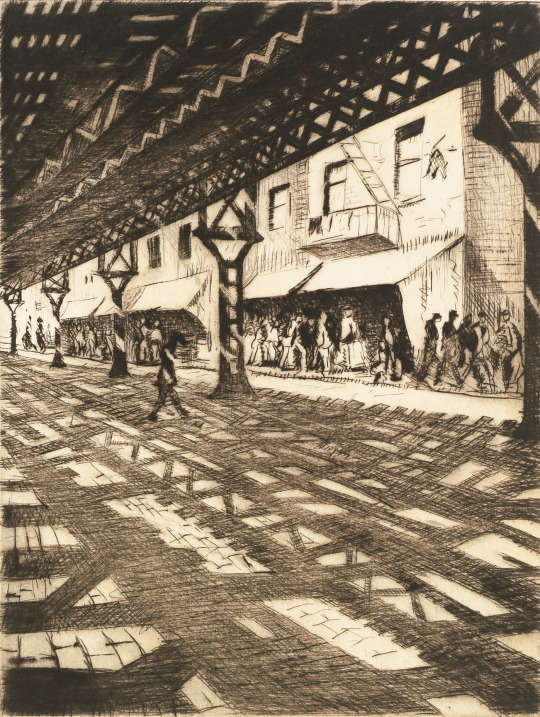

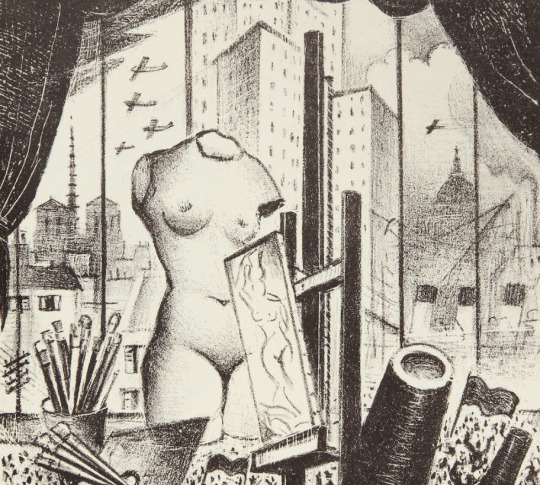

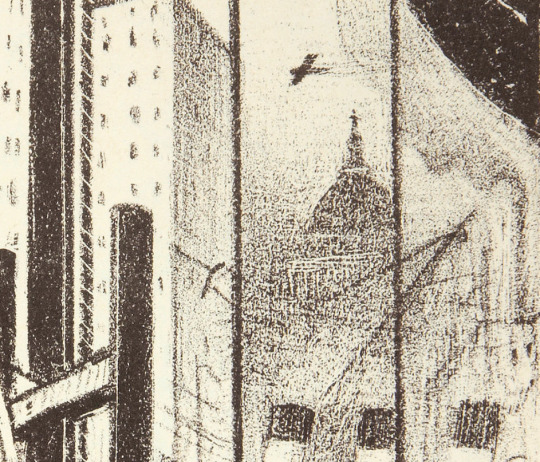

R.P. Bevan sends a fine landscape “The Corner House,” which shows that he has learnt match from Cezanne without losing his own individuality. The excessive pink and mauve of his earlier work now makes place for dignified colour. His design has significance and weight. Harold Gillman’s best picture here, the interior of a fruit market, is a beautiful harmony in greens, whilst Charles Ginner expresses the greyness of things in a fine painting of Leeds Canal. Mark Gertler shows two intoxications of colour which we are sure were painted in the true spirit of joie de vivre. One piece of sculpture alone is on view, and that by C.R.W. Nevinson.

For the nation – A marble statue by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska has recently been presented to the South Kensington Museum, together with a number of this sculptors drawings.

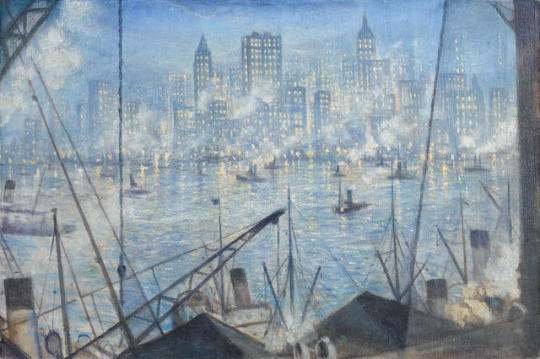

Frederick Porter, a young painter at present residing in London and a New Zealander by birth, is a colourist of considerable merit. Porter studied at the Academy Julian in Paris from 1907 to 1910. He has also painted with success the landscape of Barbizon, particularly Moret, made famous through the paintings of Tisely, and he has painted for some time in Etaples. In 1911 Porter came to London, where he has exhibited on several occasions at the London Salon. Here his work received considerable attention from discriminating critics, and as he is still a young man and intensely serious, we may expect to find augmented interest in his new work.

Two cartoons, entitled “A Place in the Sun” and “A Controller of Traffic” by Will Dyson, have been purchased by the Felton Bequest for the Melbourne National Gallery.

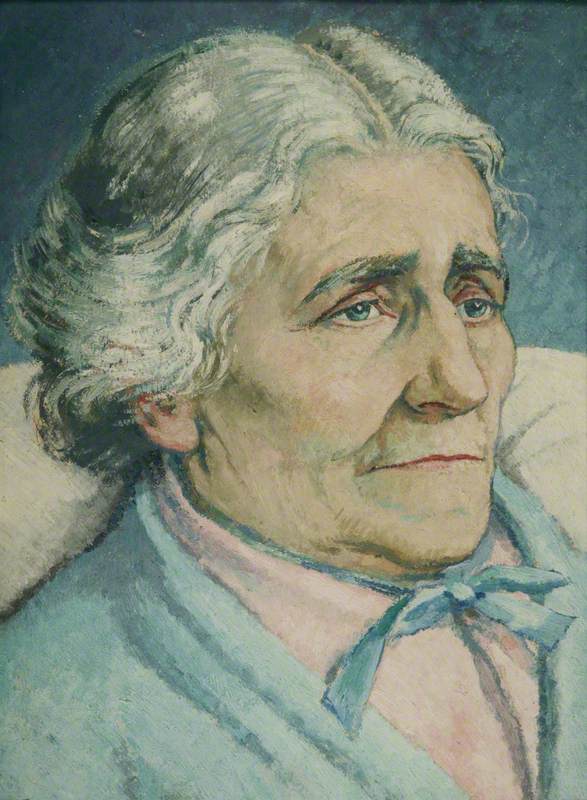

Randolph Schwabe – Head of an Old Woman

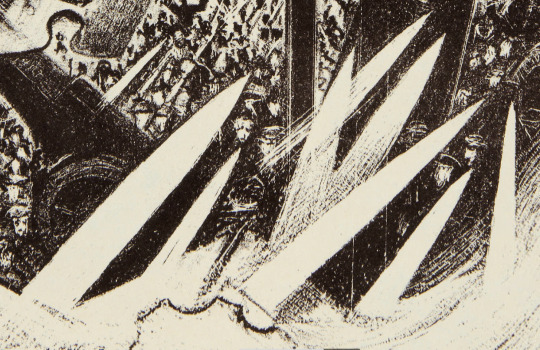

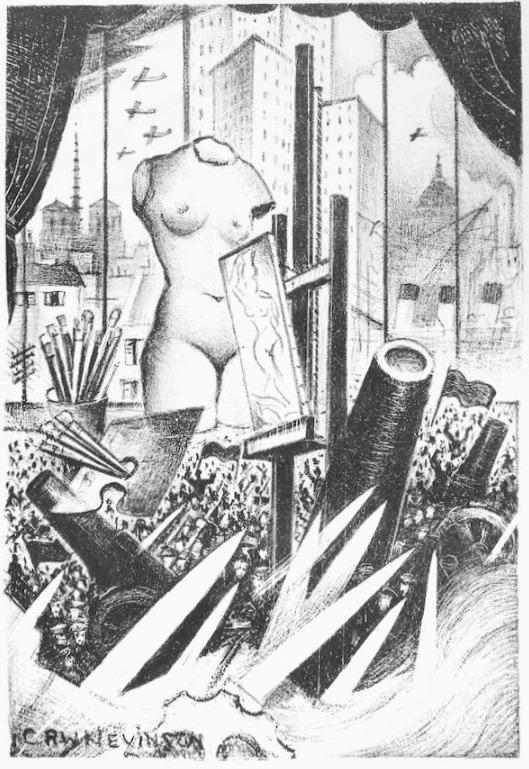

Christopher R. W. Nevinson – Bursting Shell, 1915

Artists on show:

William Ratcliffe – The Old Mill

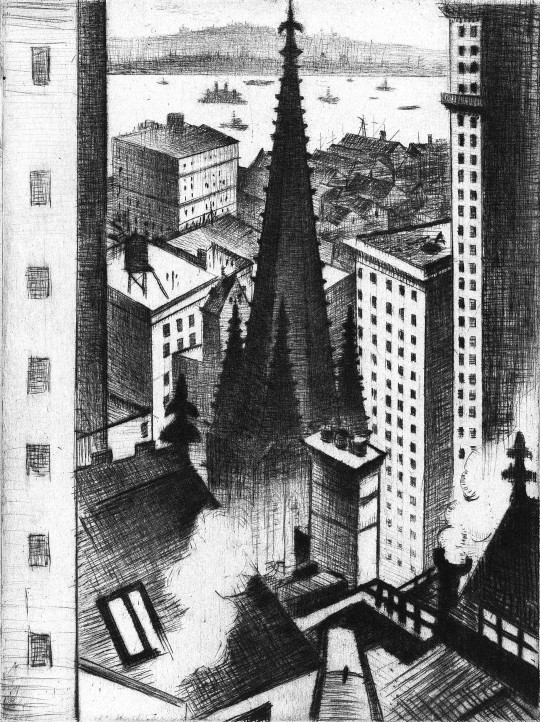

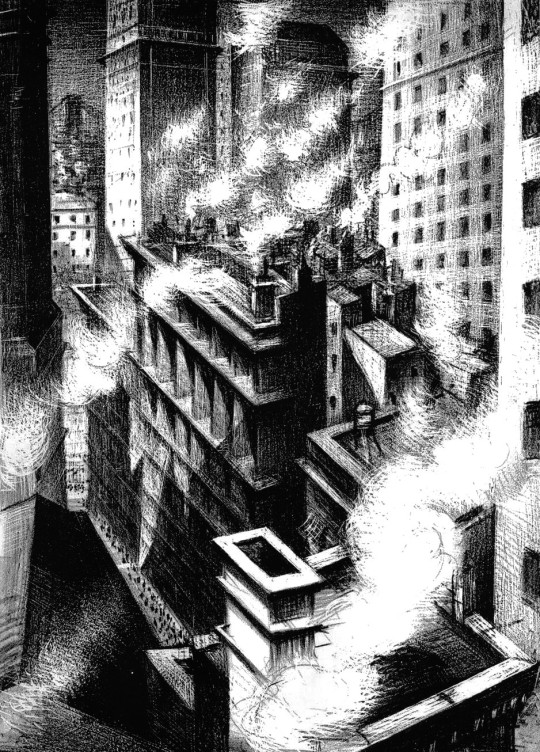

Charles Ginner – The Angel, Islington

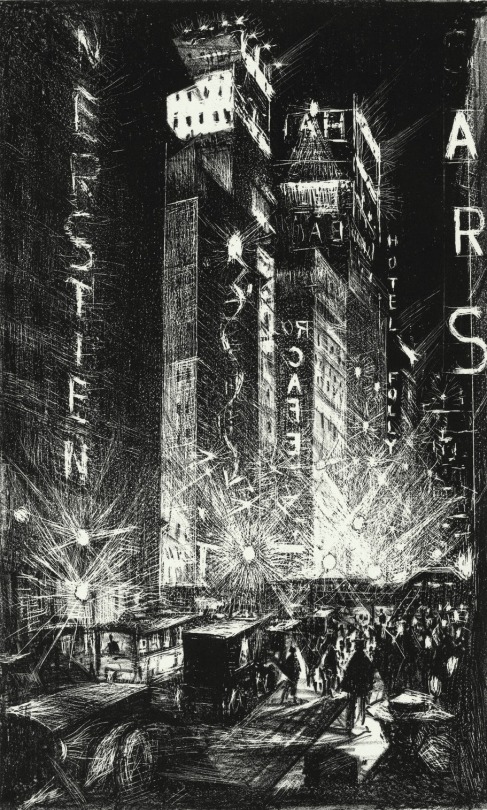

Adrian Paul Allinson – Casino de Paris

Adrian Paul Allinson – Mauve and Green

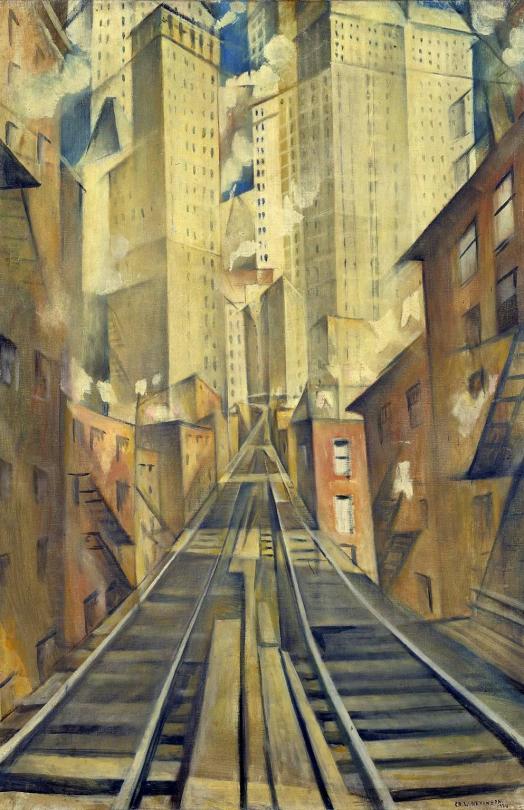

Christopher R. W. Nevinson – The Bridge at Marseilles

William Ratcliffe – The Mill Stream

William Bernard Adeney – The Spruce

William Ratcliffe – Interior

William Bernard Adeney – The Road through Woods

Mark Gertler – Swing Boat

William Bernard Adeney – Man and Horse

Charles Ginner – From Trinidad

Thérèse Lessore – An Old Woman

Stanisława de Karłowska – White Paintings

Thérèse Lessore – The Cyclist

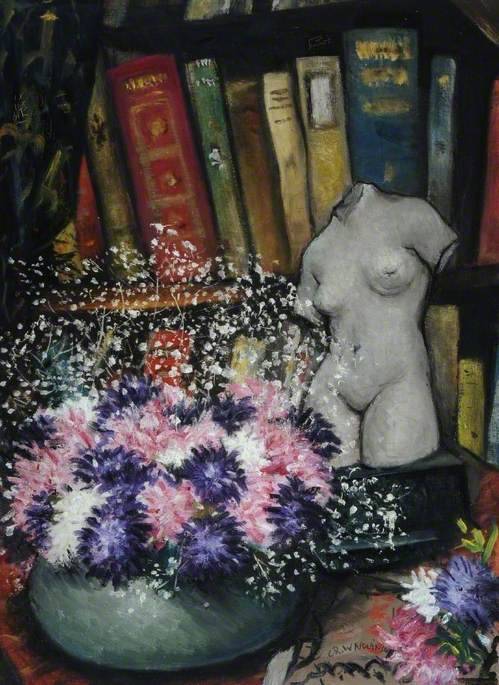

Stanisława de Karłowska – Still life

Harold Gilman – Portrait

Harold Gilman – Interior

Harold Gilman – Still Life

Adrian Paul Allinson – Queen´s Hall

Stanisława de Karłowska – Woodlands

Horace Brodzky – The Little Mourner

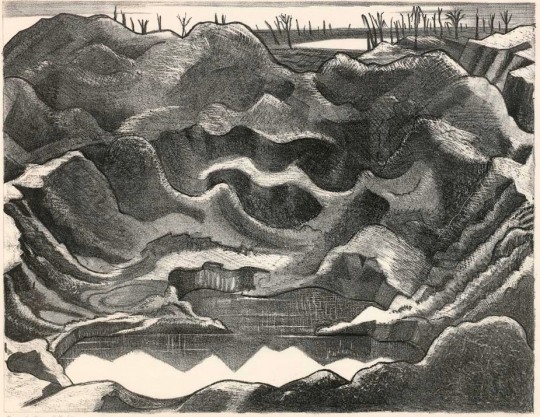

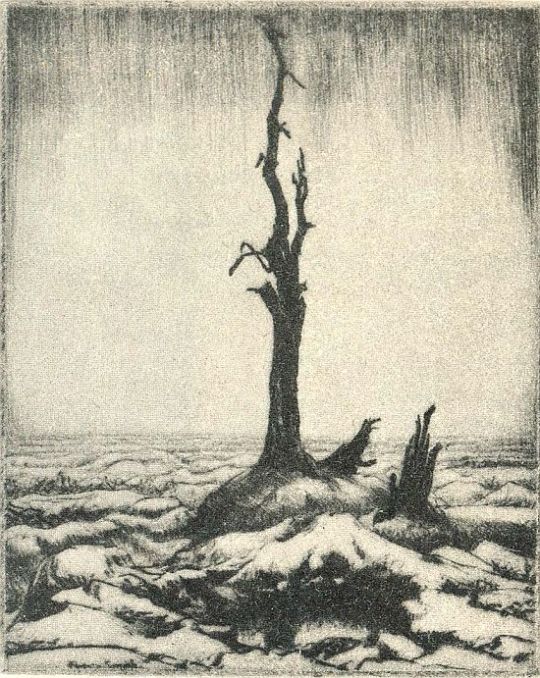

Christopher R. W. Nevinson – A Deserted Trench

Thérèse Lessore – King Street

Robert Polhill Bevan – A Hillside, Devon

John Northcote Nash – Pine Woods

Horace Brodzky – Portrait

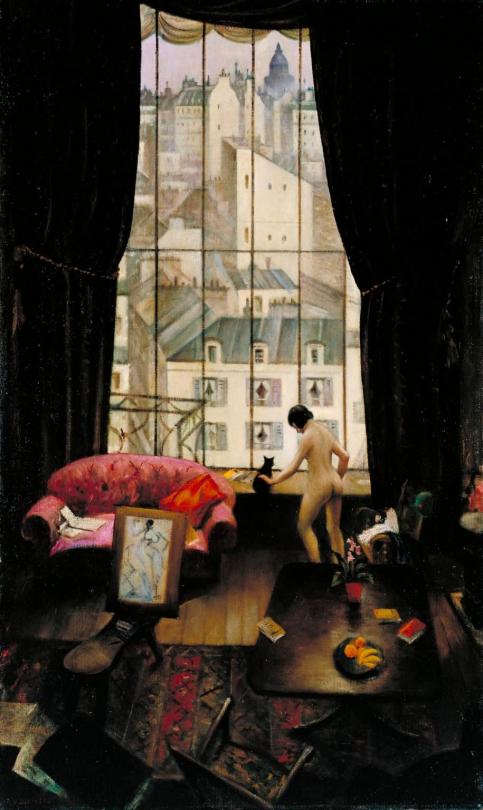

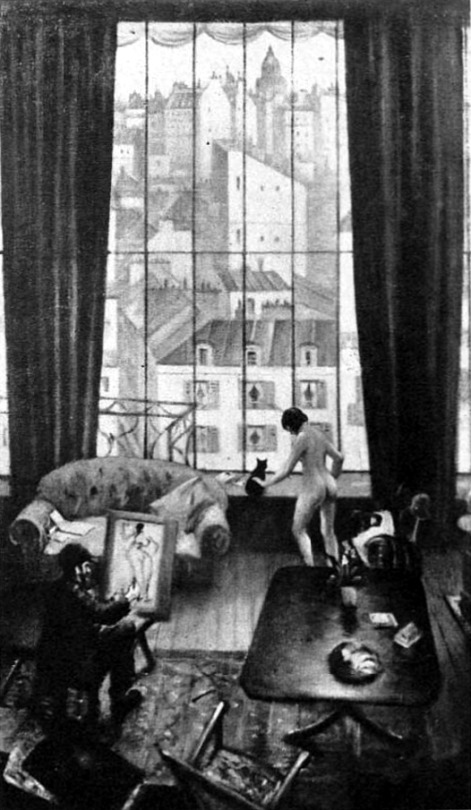

Mary Godwin – The Bedroom

Mary Godwin – Fish

Walter Taylor – Brighton

Walter Taylor – The Boat House

Randolph Schwabe – Mrs. Randolph Schwabe

Paul Nash – Tree Tops

Paul Nash – A Sunset

Paul Nash – Moonrise over Orchard

Paul Nash – Tryon´s Garden

Mary Godwin – Ways and Means

Douglas Fox Pitt – Brighton Front

Douglas Fox Pitt – Shoreham

Randolph Schwabe – Portrait

Charles Ginner – Surrey Landscape

John Northcote Nash – Landscape

John Northcote Nash – Steam Ploughing

Horace Brodzky – Expulsion

Sylvia Gosse – Versailles

Sylvia Gosse – The Toilet

Sylvia Gosse – Busch Bilderbogen

Sylvia Gosse – The Answer that turneth away Wrath

Sylvia Gosse – Sussex Meadows

Randolph Schwabe – Landscape in Devonshire

William Bernard Adeney – Dividing Roads

William Bernard Adeney – House and Trees

Thérèse Lessore – The Canal Bridge

Stanisława de Karłowska – The Lane

Stanisława de Karłowska – From an Upper Window

Mary Godwin – Still Life

Mary Godwin – Ewelme Alms House

Robert Polhill Bevan – The Corner House

Robert Polhill Bevan – Tattersall´s

Harold Gilman – My Lonely Bed

Thérèse Lessore – The Confectioner´s Shop

Adrian Paul Allinson – Cotswolds, Spring

Walter Taylor – Interior

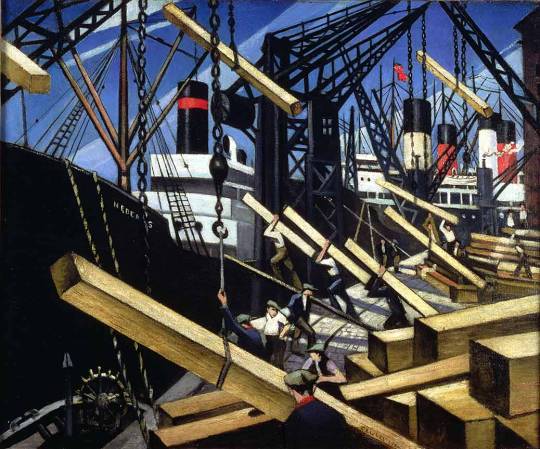

Charles Ginner – The Timber Yard, Leeds

Charles Ginner – Crown Point, Leeds

John Northcote Nash – Threshings

John Northcote Nash – Woods

Adrian Paul Allinson – Still Life

Horace Brodzky – Decoration

Horace Brodzky – Cefalu

Mark Gertler – Fruit Stall

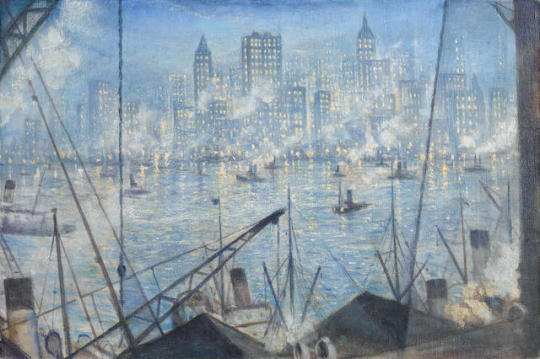

William Ratcliffe – London

Douglas Fox Pitt – In the Dome, Brighton