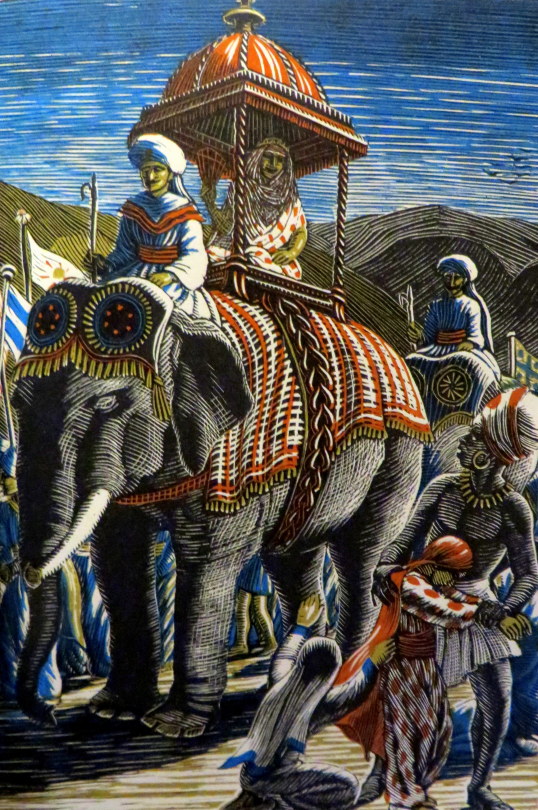

In a past post I wrote about the Cambridge Book of Poetry for Children, edited by Kenneth Grahame with 54 wood-engravings by Raverat. All of them black and white. This is a post about her colour wood engravings from The Bird Talisman.

Gwen Raverat, the granddaughter of Charles Darwin, was an English wood engraver and author. Born and raised in Cambridge, England, she studied art at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1908 and studied under Frederick Brown and Henry Tonks. She was inspired by Thomas Bewick’s wood engravings but the Slade at that time gave no opportunities to study wood engraving. When she left the Slade she went to Paris to the Sorbonne where she met and married Jacques Pierre Raverat, a fellow student and draughtsman.

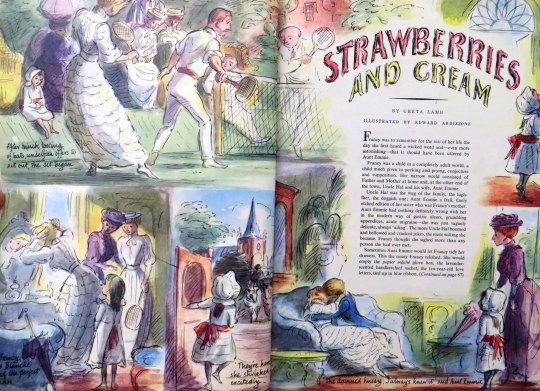

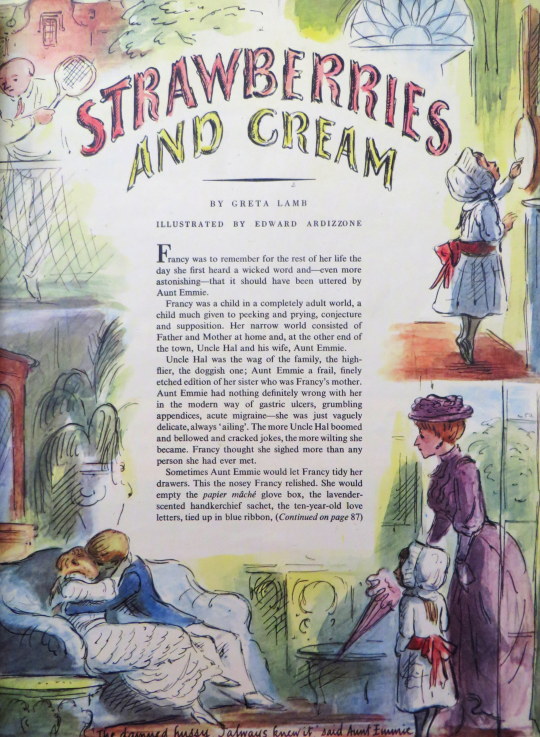

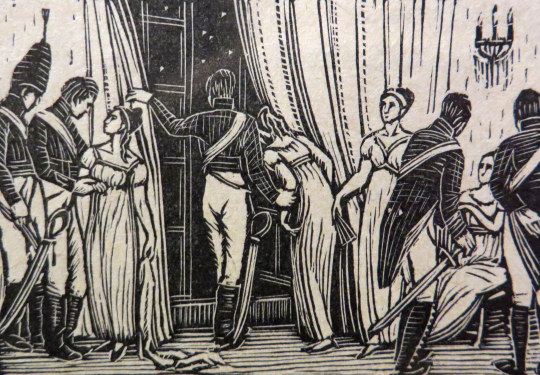

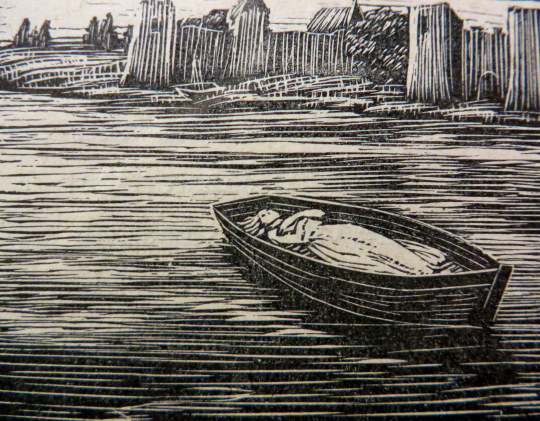

These images come from The Bird Talisman is a story written by Raverat’s great uncle, Henry Allen Wedgwood, a London barrister. He originally published it with illustrations by the himself in The Family Tutor in 1852 and then later in book form in 1887.

Gwen took it upon herself to re-illustrate the book with her wood engravings.

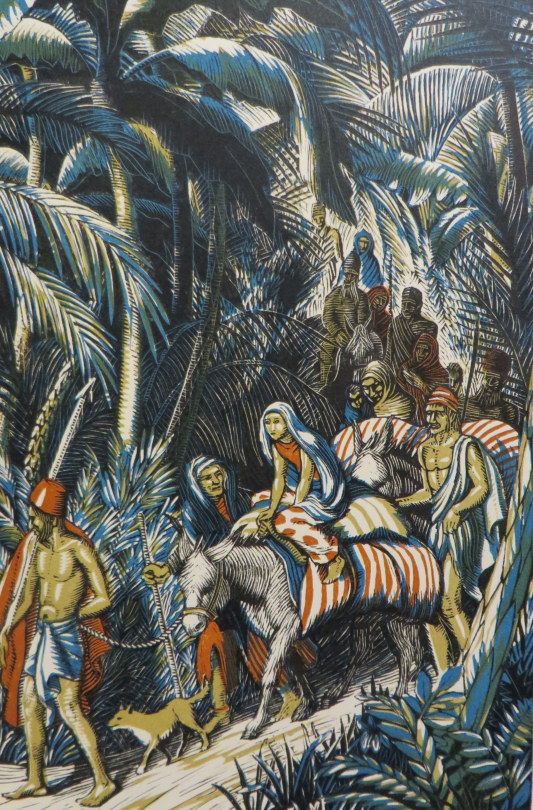

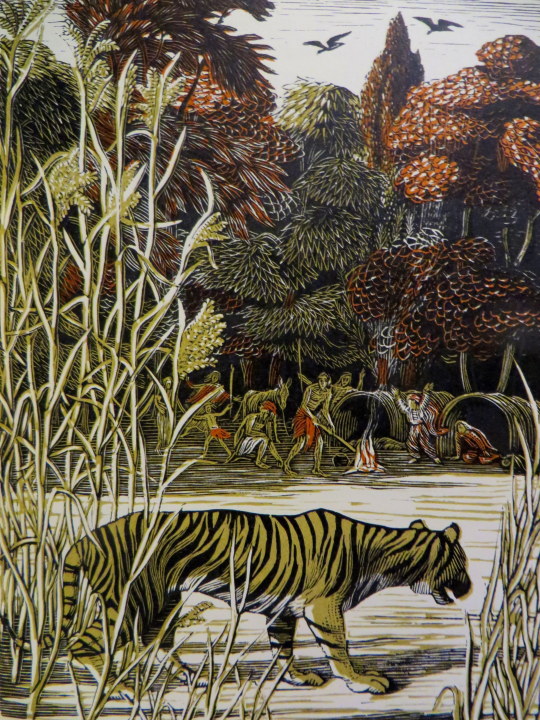

She overcame her feeling of “sacrilege in tampering with a sacred work” and tried to illustrate it herself for Faber and Faber. It did not worry her that she had never visited India, where the story is set, for neither had her great uncle; and neither of them made any effort to be accurately Indian.

Her interest in colour printing, which had first appeared in the frontispiece to Four Tales from Hans Andersen, is here developed with rich effect in eight full-page colour plates. †

She held off agreeing to a contract until she had experimented one of these and settled how to do the various cuts. She decided in each to undertake the main block herself, but to hand over to a blockmaker those that would carry the colour. When de la Mare arranged for these to be done in Vienna, Gwen objected, owing to the German occupation of Austria, and asked to estimate the cost of Austrian blocks, postage and insurance against the of using either English or French blockmakers as she was willing to pay the difference. †

In the end she used an English blockmaker she knew and trusted outlining for him the colour on the second block. She herself cut the plentiful smaller black-and-white engravings, in a variety of shapes and sizes, which help make this the most sumptuously decorated of all her books.It was contracted in February 1939 and due to be delivered in May of that year, but took longer, owing to the painstaking work involved. †

At one point the imminence of war cast doubt over the book’s production. “It’s now so nearly finished that I do hope it will get actually printed and bound, war or no war,” she wrote to Richard de la Mare in late August 1939, “that is I should hope this, if I could think about anything but war.” More positively, she wrote: “I hope you will like the colour plates; they are, at any rate, just what I intended them to be.” She threw further encouragement his way, reminding him that in the last war people had bought a lot of books, “especially if they were absolutely non-topical – quite away from war subjects, which this is. And there’s always Christmas for children even in war. However,” she ended, unable to stem her own despair, “nothing really matters much does it?” †

The book did, however, get published, though work on it was slow for by the time they started printing half the men at the Press had been called up. (This may have limited the number produced in 1939 and helps explain why a second edition was produced in 1945, soon after the return to peace.) †

† Gwen Raverat: Friends, Family and Affections by Frances Spalding, p357, 2001.