The Phoney War was an eight-month period at the start of World War II in 1939 during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germany’s Saar district. During this time the Nazi’s had invaded Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia. On 10 May 1940, eight months after Britain and France had declared war on Germany, Nazi troops marched into Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, marking the end of the Phoney War and the start of Germany being an advancing danger to the British. Some months later the Germans took control of Guernsey and Jersey. The British activities in the war were mostly at sea with the Navy disabling German shipping in an economic blockade and the troops on the mainland of Europe were drawn back to the retreat in Dunkirk.

Trafalgar Square, October 1941

It was around this time that the National Gallery collection of paintings was to be evacuated out of London as from September 1940 to May 1941 the Blitz happened, by mistake.

The first German attack on London actually occurred by accident. On the night of August 24, 1940, Luftwaffe bombers aiming for military targets on the outskirts of London drifted off course and instead dropped their bombs on the centre of London destroying several homes and killing civilians. Amid the public outrage that followed, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, believing it was a deliberate attack, ordered Berlin to be bombed the next evening.

About 40 British bombers managed to reach Berlin and inflicted minimal property damage. However, the Germans were utterly stunned by the British air-attack on Hitler’s capital. It was the first time bombs had ever fallen on Berlin. Making matters worse, they had been repeatedly assured by Luftwaffe Chief, Hermann Göring, that it could never happen. A second British bombing raid on the night of August 28/29 resulted in Germans killed on the ground. Two nights later, a third attack occurred. German nerves were frayed. The Nazis were outraged. In a speech delivered on September 4, Hitler threatened, “When the British Air Force drops two or three or four thousand kilograms of bombs, then we will in one night drop 150-, 230-, 300- or 400,000 kilograms. When they declare that they will increase their attacks on our cities, then we will raze their cities to the ground. We will stop the handiwork of those night air pirates, so help us God!”

Beginning on September 7, 1940, and for a total of 57 consecutive nights, London was bombed. The decision to wage a massive bombing campaign against London and other English cities would prove to be one of the most fateful of the war. Up to that point, the Luftwaffe had targeted Royal Air Force airfields and support installations and had nearly destroyed the entire British air defence system. Switching to an all-out attack on British cities gave RAF Fighter Command a desperately needed break and the opportunity to rebuild damaged airfields, train new pilots and repair aircraft. “It was,” Churchill later wrote, “therefore with a sense of relief that Fighter Command felt the German attack turn on to London”. †

The feeling was it was unwise to have the National Galleries collection separate in locations as one location would save on guarding the works and help keep the location more secret and avoid any potential losses of work in transportation or admin. The curators could also monitor the condition of the paintings too.

One serious proposal was for the paintings to be evacuated by ship to Canada. But the vulnerability of the ships to U-boat attack worried the Gallery’s director, Kenneth Clark. He went to see Winston Churchill who immediately vetoed the idea: ‘Hide them in caves and cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island’.

The danger of shipping was just as worrying as the dangers on the dockland. One chance bomb could wipe out the whole collection in a dockland warehouse while waiting to be loaded.

Martin Pritchard – Manod Quarry, 2008

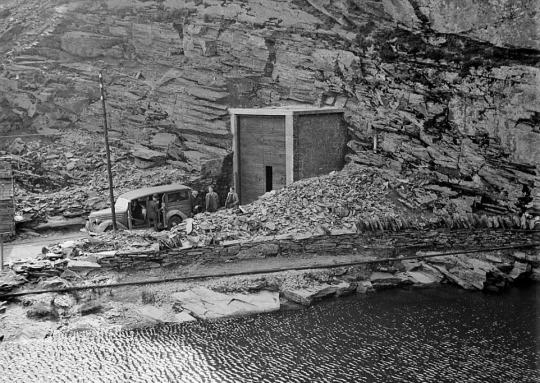

Manod Quarry, 1940s

The Welsh quarry of Manod was chosen as the best location. After the quarries entrance was widened with explosive blasts so that trucks could drive inside, the next task was to build man structure inside to house the collection.

Lee McGrath – Inside Manod Quarry, 2018

These brick buildings (like bungalows) were built inside the cave quarry with roofs and picture racks. There were thermostat and humidity controllers to stop the paintings becoming damp or suffering changes in temperature. By the end of the Blitz the whole collection was now housed in the cave.

Manod Quarry – Inside the Art Bungalows housing the National Collection.

It had long been known that paintings were happiest in conditions of stable humidity and temperature. But it had never been possible to monitor a whole collection in such controlled circumstances before. Valuable discoveries were made during this time which were to influence the way the collection was displayed and cared for once back in London after the war.

It was also an opportunity for Martin Davies, the Assistant Keeper in charge of the paintings in Wales, to complete his research for new editions of the National Gallery’s permanent collection catalogues. ‡

Manod Quarry – Inside the Art Bungalows housing the National Collection.

The precautions were wise as the National Gallery was hit by nine bombs between October 1940 and April 1941.

The collection returned to London by the end of 1945 but the caves were held as government property in case they were needed during the Cold War.

The curious thing about the nations art during wartime was it didn’t all get put together. The National Gallery had the quarry in Manod but the National Portrait Gallery moved their collection to Mentmore House, in Buckinghamshire. The Gallery evacuated its portraits to Mentmore’s outbuildings.

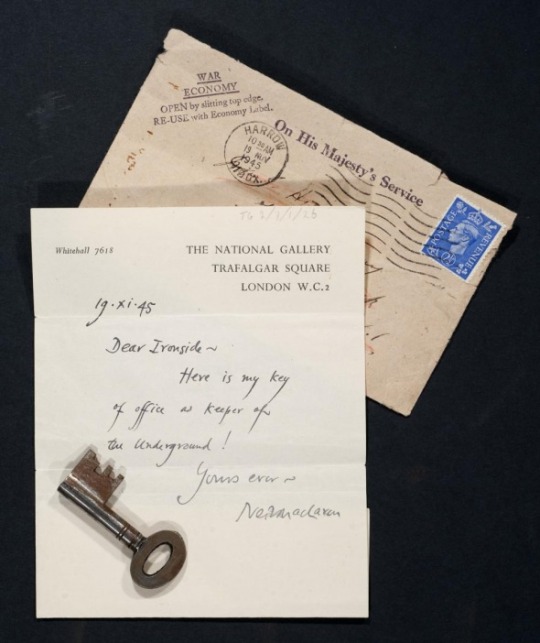

The Tate Gallery had moved their works, to a disused stations on the Piccadilly London Underground network.

Photograph of a letter to Robin Ironside with the key to the Piccadilly Underground storeroom from Neil MacLaren.