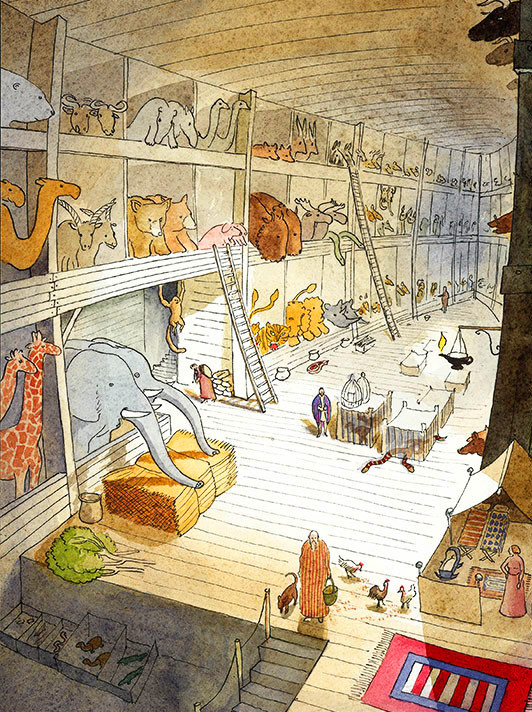

Warwick Hutton – Interior of Noah’s Ark, 1977

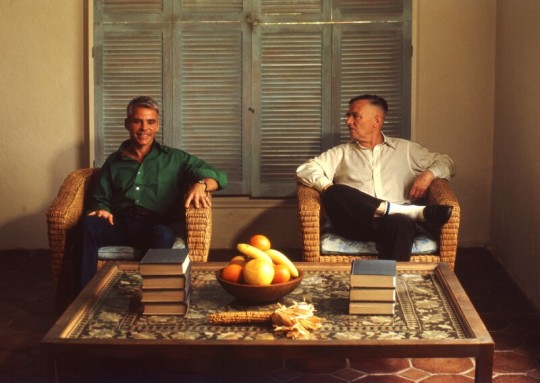

The work of Warwick Hutton is a bit of a rarity in the UK sadly. In Cambridge (where I live) he is known as a teacher as he was head of Fine Art at the Cambridge School of Art. Across the UK he is known as a painter and wood engraver and internationally he is remembered as an illustrator.

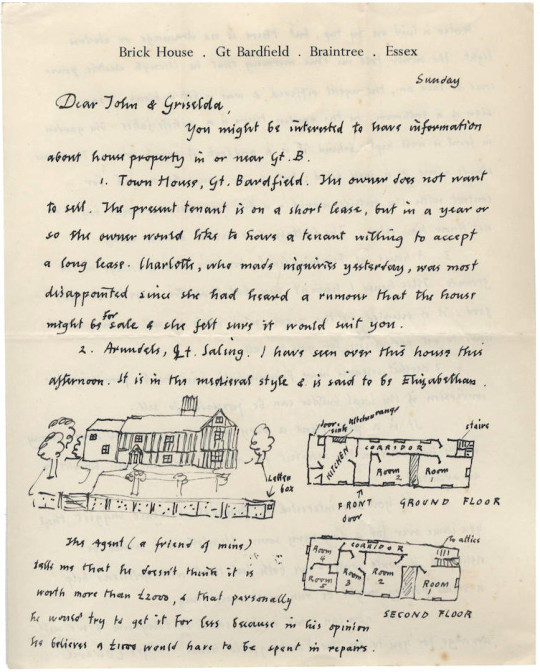

Hutton was born in England to an artistic family originally from New Zealand. His father was the glass engraver John Hutton (famous for the windows at Coventry) and his mother was Helen (Nell) nee Blair a talented painter. In 1939 the couple had twins, Macaillan (Cailey) John Hutton and Warwick (Wocky) Blair Hutton.

Warwick attended the Colchester School of Art where John O’Connor was the Principle and John Nash was teaching Botanical drawing. Richard Chopping was also teaching there. There Hutton met Elizabeth Mills and they were married in 1965.

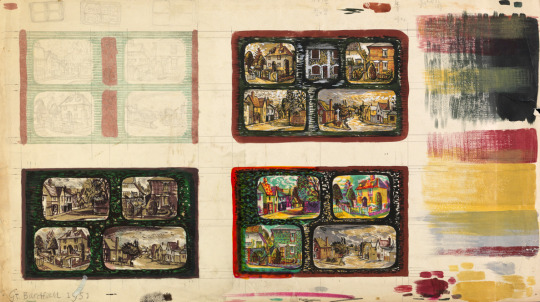

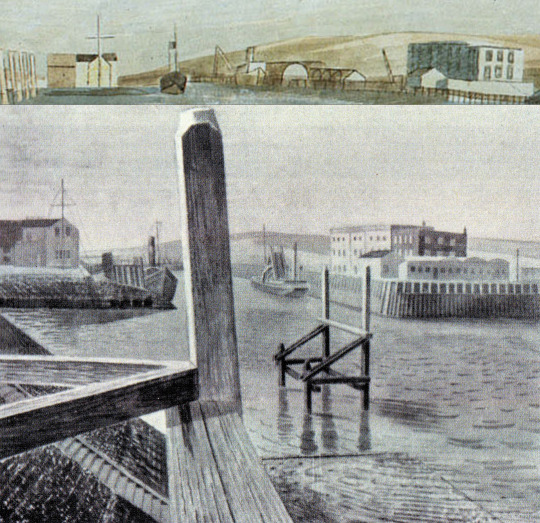

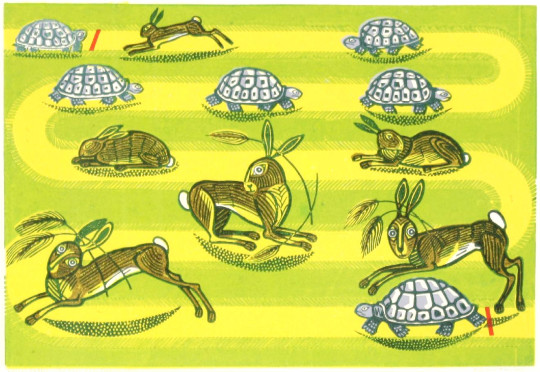

Warwick Hutton – Two illustrations from Cats Free and Familiar, 1975

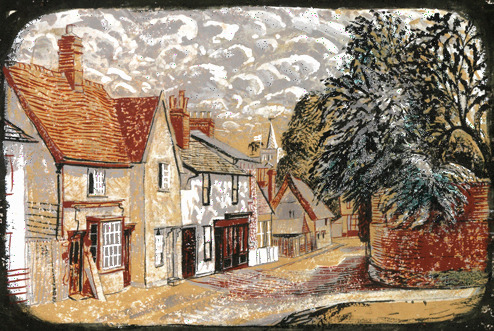

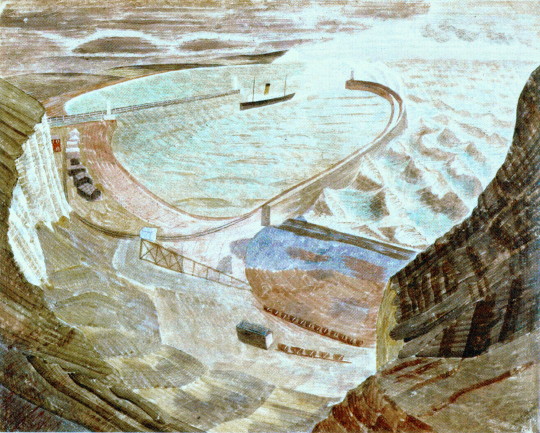

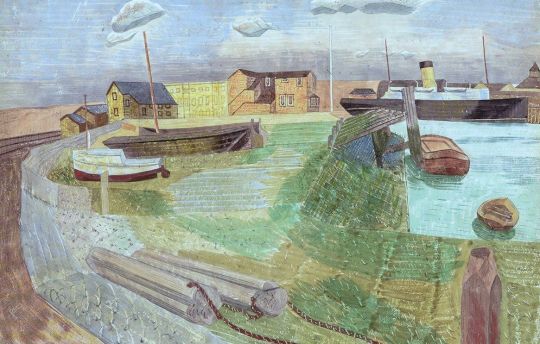

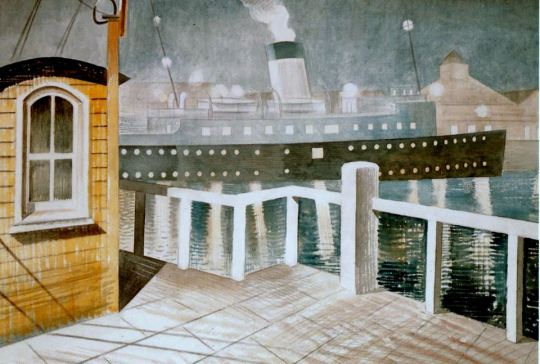

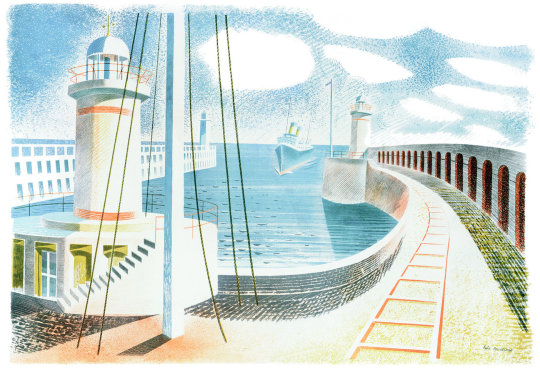

Warwick was working as an illustrator while helping his father engrave and install the windows for Coventry Cathedral. He worked for small private presses and major publishers, from the The Keepsake Press (Throwaway Lines, Cats Free and Familiar, Rider And Horse.) to the Cambridge University Press and their limited edition Christmas Book series (Waterways of the Fens, A Printer’s Christmas Books).

One of Hutton’s illustrations appeared in John O’Connors book The Technique Of Wood Engraving. Three years later Warwick published his own book Making Woodcuts with Academy Editions Ltd.

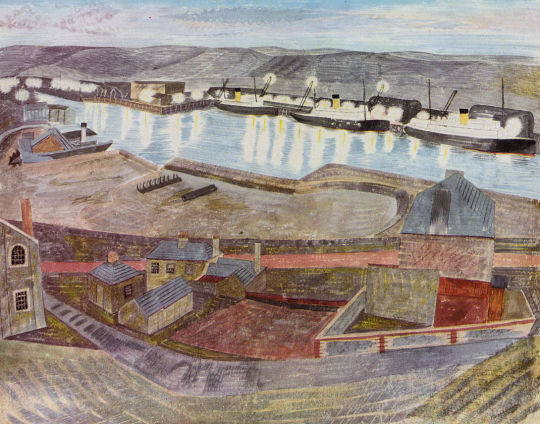

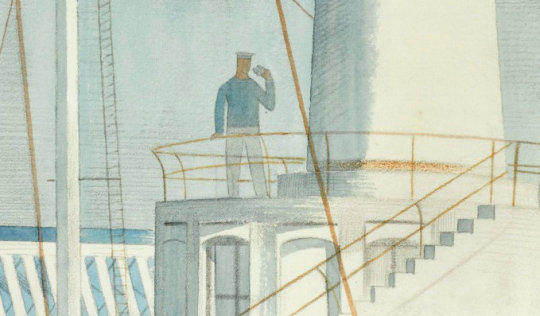

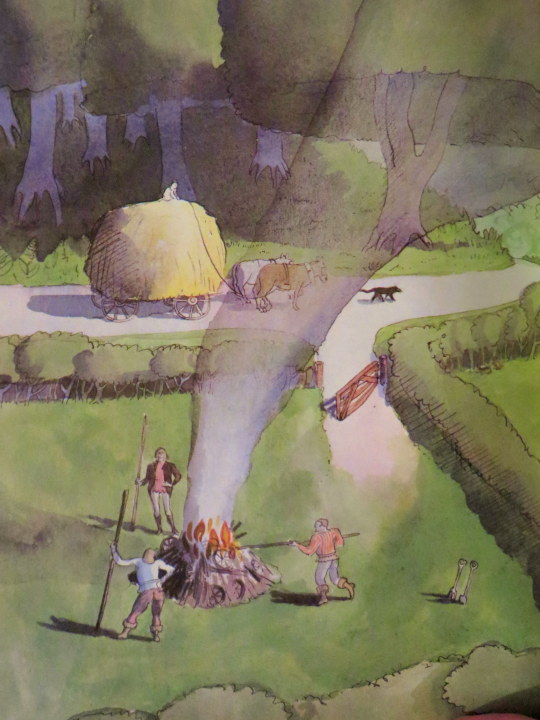

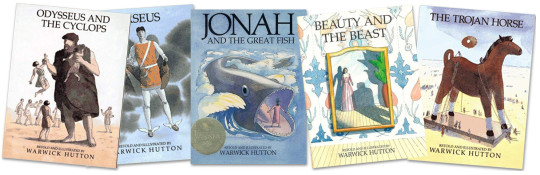

The major successes for Warwick Hutton were to come with a series of retelling of Bible Stories (Noah and the Great Flood, Jonah and the Great Fish, Moses in the Bulrushes) and Grimm’s Tales (Beauty and the Beast, The Nose Tree, The Tinderbox, The Sleeping Beauty) all of these internationally published.

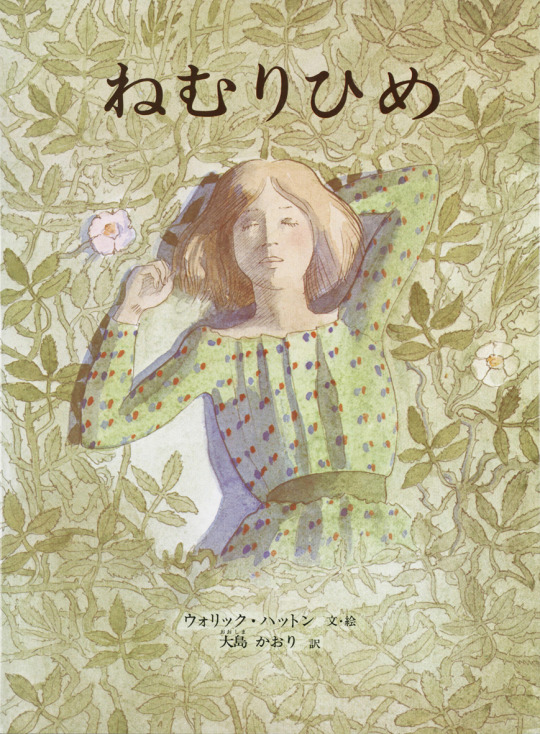

ウォリックハットン – ねむりひめ, 1979

My two favourites are the Adam and Eve story for it not being shy about nakedness in children’s books and Sleeping Beauty for the wonderful use of the rose thorns and the patterns used throughout the book.

Warwick Hutton – Illustration from The Sleeping Beauty, 1986

The most attention came for Hutton when he worked with Susan Cooper, the author best known for The Dark Is Rising series. Hutton illustrated three books for Cooper: The Selkie Girl, Tam Lin and the Silver Cow for her, many of these are still in American libraries.

The later series of books by Hutton were re-telling of Greek Myths, Odysseus and the Cyclops, Persephone, Perseus, Theseus And The Minotaur the latter gaining much attention as mentioned in the New York Times Children’s Book Award review below:

The gifted British watercolorist turns to Greek myth and captures the bravery of young Theseus, the terrifying half-human Minotaur and the haunting beauty of ancient Crete. Here, as in all his other books, the ocean scenes have astonishing intensity and power. †

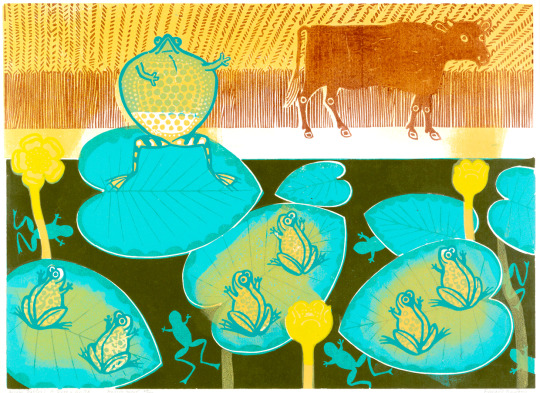

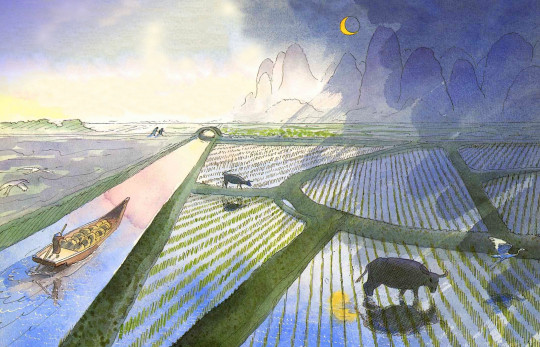

Hutton collaborated with other authors illustrating their books: Margaret & Raymond Chang on The Cricket Warrior: A Chinese Tale and James Sage on To Sleep.

Warwick Hutton – Illustration from The Cricket Warrior, 1994

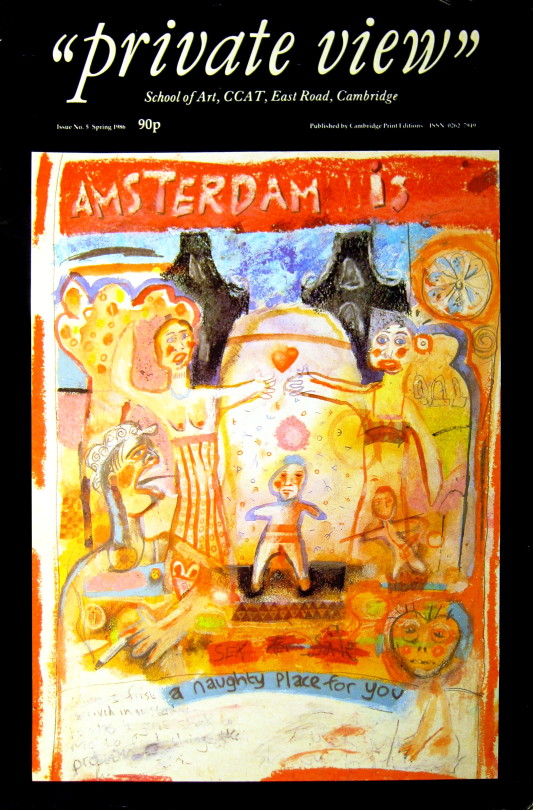

Becoming Head of the Foundation course at the Cambridge School of Art Hutton was able to encourage the students to publish their works and set up and edited

Private View: The Journal from the Cambridge School of Art. The magazine republished works by famous artists as well as the students own work.

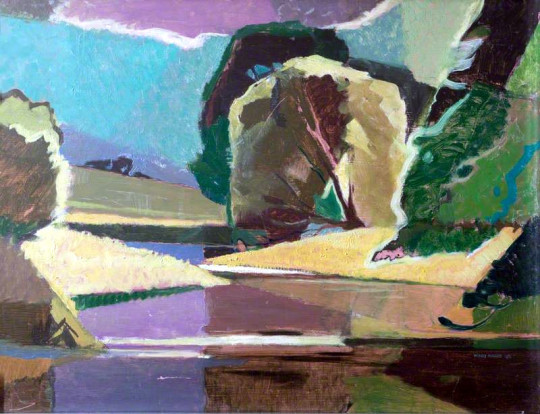

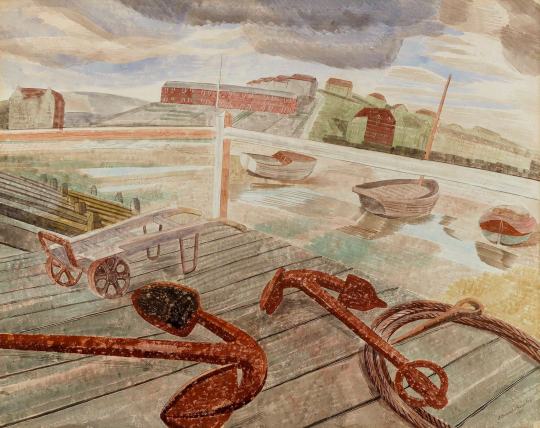

As a teacher at the Cambridge School of Art, Warwick provided the Council with a painting as part of the Original Works for Children in Cambridgeshire, part of the Pictures for Schools series. The Pictures for Schools project came out of, and alongside many other famous ‘utopian’ projects like Contemporary Lithographs (1937-38), AIA Everyman’s Prints (1940) and the School Prints series of lithographs where major artists would be paid to design a lithograph that would be printed in thousands and then sold to schools cheaply.

In the founding of the Pictures for Schools project Nan Youngman wanted to have paintings more than prints from artists. Early contributors were L. S. Lowry, Tirzah Garwood, Stephen Bone and Bernard Cheese. After some decades it was taken over by Walter Hoyle who was the head of Printmaking at the Cambridge School of Art. Together they encouraged their student’s to donate works to the collection to be hung in schools.

Hutton’s painting of ‘Adam and Eve’ followed with a book he published in 1987 under the same name by Hutton with Atheneum Books.

Warwick Hutton – Adam and Eve, 1986 (In My Collection)

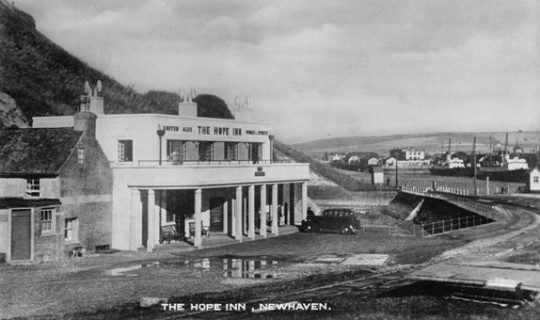

Hutton died of cancer in 1994 in Cambridge, England. An audiobook of Jonah and the Great Fish is for sale in the USA as an audiobook and a video can be found here. Interior of Noah’s Ark can be purchased as a card from Orwell Press Art Publishing.

Private View: The Journal from the Cambridge School of Art.

Bibliography

Throwaway Lines

by Gavin Ewart, Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1964Waterways of the Fens

by Peter Eden, Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1972Making Woodcuts

by Warwick Hutton, 1974Practical Gemstone Craft

by Helen Hutton. Illustrated by Warwick Hutton. 1974.Cats Free and Familiar

by Robert Leach, Illustrated by Warwick Hutton. 1975Rider and Horse

by Martin Booth, Illustrated by Warwick Hutton. 1976Noah and the Great Flood

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1977Mosaic Making Techniques

by Helen Hutton, 1977The Sleeping Beauty

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1979The Nose Tree

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1981Private View – Cambridge School of Art Magazine

Editor and co-editor, 1982-1989The Silver Cow: A Welsh Tale

by Susan Cooper. Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1983Flesh of His Flesh – Poems

by Florence Elon, Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1984Beauty and the Beast

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1985Jonah and the Great Fish

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1986Moses in the Bulrushes

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1986The Selkie Girl

by Susan Cooper. Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1986Adam and Eve – The Bible Story

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton. 1987The Tinderbox

by Hans Christian Andersen and re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1988Theseus And The Minotaur

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1989To Sleep

by James Sage. Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1990Tam Lin

by Susan Cooper, Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1991The Cricket Warrior – A Chinese Tale

retold by Margaret & Reymond Chang, Illustrated by Warwick HuttonPerseus

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1993Persephone

re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1994Odysseus and the Cyclops

by Homer and re-told and Illustrated by Warwick Hutton, 1995.

† Published: New York Times. November 5, 1989