Here are some recent photographs of Bridge End Gardens that are just behind the Fry Art Gallery.

Here are some recent photographs of Bridge End Gardens that are just behind the Fry Art Gallery.

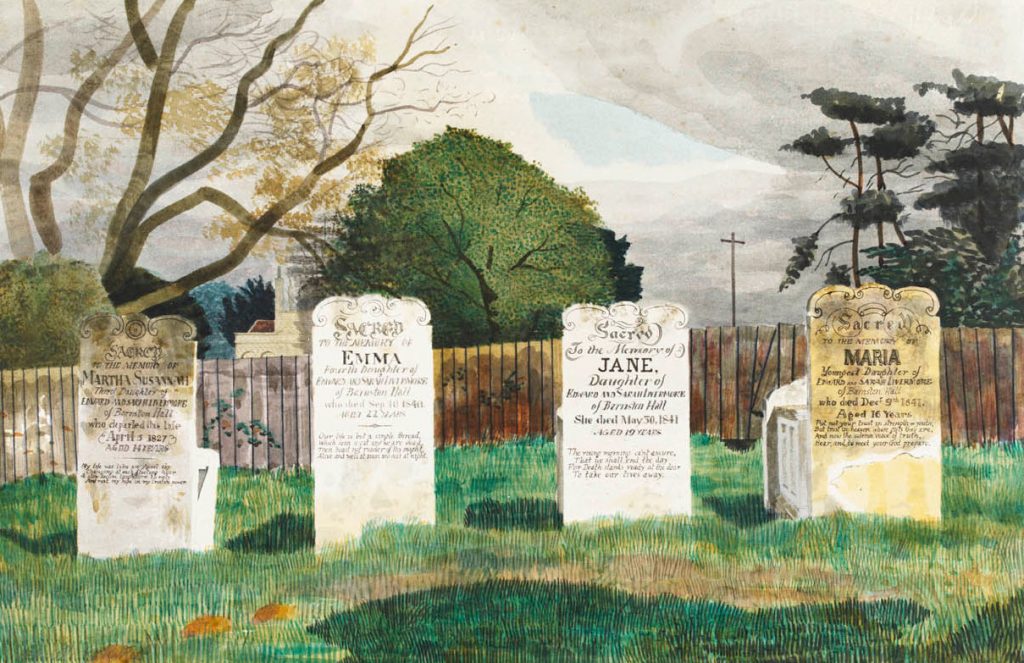

The legacy of the Livermore sisters lives on in their rather beautiful gravestones in Barnston, Essex. They were painted by Kenneth Rowntree for the Recording Britain and being interested in typography I find them interesting. In 1941 Kenneth Rowntree had also moved to Great Bardfield, settling with his wife Diana (née Buckley) into the “a handsome draughty house” Town House. The sisters histories were rather sad however.

Kenneth Rowntree – The Livermore Tombs, Barnston, Essex, 1940

The Livermores were a large nineteenth century family who lived at the Hall in Barnston. Each grave has a poem but I am not sure were, my guess based on the tone is that they are poetic themes inspired by the Book of Common Prayer.

Martha 14 years old (d 1827) A slow decline

My life was like an April sky

Changing at each fleeting hour

A slow decline taught me to rely

And rest my hope in my Creators power

Emma 22 years old (d 1840) Thrown from her horse

Our life is but a single thread

Which soon is cut and we are dead

Then boast not reader of thy might

Alive and well at noon and dead at night

Jane 19 years old (d 1841) Heart attack

The rising morning ca’nt assure

That we shall end the day

For Death stands ready at the door

To take our lives away

Maria 16 years old (d 1841) Smallpox

Put not your trust in strength or youth

But trust in Heaven whose gifts they are

And now the solemn voice of truth

Hear, and to meet thine God prepare

Barnston Hall, Essex.

This is a post about the back of Brick House, the home of Edward Bawden in Great Bardfield. It is an odd thing but many artists ended up painting the back of Bawden’s house more than the front. One would guess they were painted during parties or over weekends.

Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious were young artists, they met as students at the Royal College of Art, London, in 1922. Bawden and Ravilious moved into Essex in 1925, Cycling around the area they came across Brick House, Great Bardfield where they rented rooms from Mrs Kinnear, a retired ship-stewardess, for weekends away from London.

Ronald Maddox – Brick House, 1960

Brick House is an early 18th Century red brick house with two floors and windowed attics. The property had two staircases, so when the house was rented it was divided into two parts with a shared kitchen and scullery. It had been the home of a carriage maker, a girls school, and a coffin maker in it’s past. Mrs Kinnear rented rooms but lived her with two daughters and her dog.

When Edward Bawden married Charlotte Epton in 1932, Edward’s father bought them Brick House as a wedding gift and Charlotte’s father, who was a solicitor took care of the paperwork.

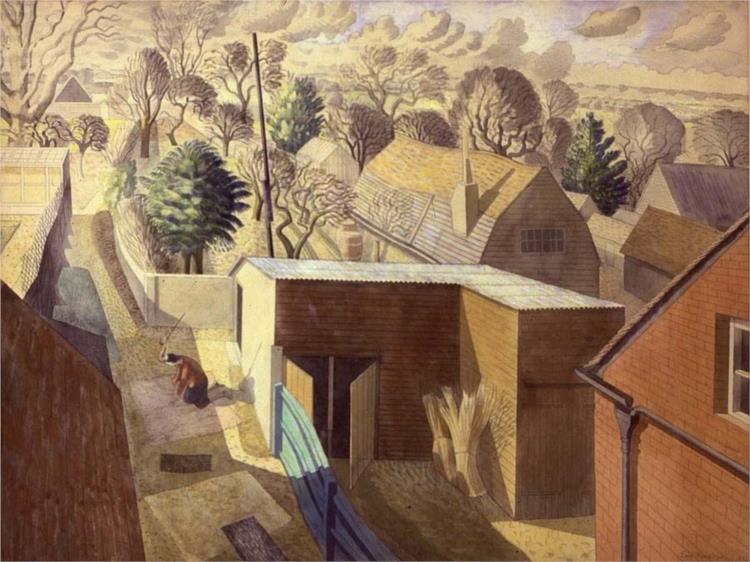

The first picture here, by Eric Ravilious is painted from the top of the house. At this time the roof was being repaired and retiled as it was in poor condition after purchase. Edward and Eric both climbed up the ladders to the roof to paint the view, you can see more of the guttering to the right of the picture below than you could from the view of Edward’s studio.

Eric Ravilious – Prospect from an Attic, 1932

The picture below by Bawden shows the roof being repaired by Elisha Parker and Eric Townsend and their ladder to the roof. Even though the house was sold, Mrs Kinnear (the old landlady) had left all her possessions in the building while she took up a Housekeeper post in the New Forest. Charlotte managed to arrange that the possessions would be stored in the Village Hall and with the help of Mrs Townsend (Eric’s mother, who was also the washer woman) she moved them out of the house. While the roof was repaired Charlotte Bawden cleaned and fumigated the rooms prior to them being decorated.

You can see Elisha and Eric on the roof below.

Edward Bawden – They dreamt not of a perishable home, who thus could build, 1932

The bizarre name for the painting was inspired by Mary Gwen Lloyd Thomas, one of Charlotte’s friends who edited poetry books, the quote is from Wordsworth:

They dreamt not of a perishable home who thus could build

Be mine, in hours of fear

Or grovelling thought, to seek a refuge here;

Or through the aisles of Westminster to roam;

Where bubbles burst, and folly’s dancing foam

Melts, if it cross the threshold

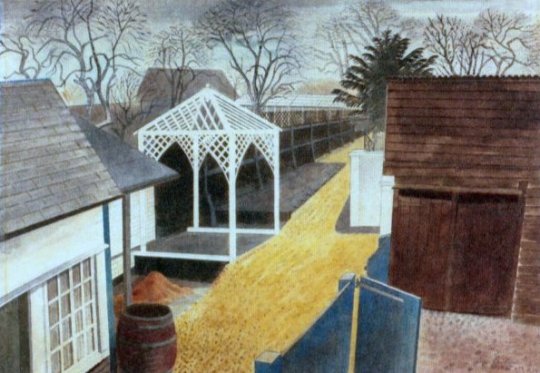

In the Garden is a little wooden trellised hut that the Raviliouses had given to the Bawden’s as a wedding present. You can see the foundations being installed in the picture above with wheelbarrows around and upturned earth (They dreamt not of a perishable home…).

It is my feeling that the picture below by Charles Mahoney was painted in 1932, likely just after the roof was completed. It is part of the collection of the Royal Academy and they date it as 1950s, likely because the missing trellis. Why do I think ’32? Well the same concrete foundations and wheelbarrows are where the trellis would later stand (the site of the buckets), and the waterbutt is to the left in Mahoney’s painting where as in the painting below it by Ravilious the waterbutt has been moved. Also the shed beside the trellis was lost in the war and replaced by one with a different roof axis. But mostly because it looks so much like the painting above.

Charles Mahoney – Barnyard (RA Say 1950’s I say 1932)

You can see the completed trellis in the picture by Ravilious below. Also the blue gates helped divide the part of the Bawden’s garden from Mrs Kinnear part of the house originally, it was also where she kept her dog. Later on as motorcars became popular the gates would divide the house from the driveway.

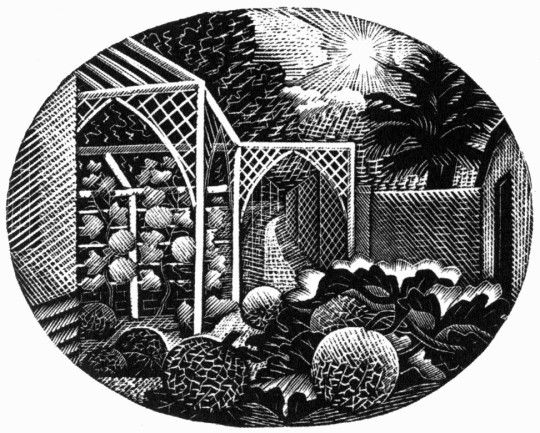

Eric Ravilious – The Garden Path, 1933

The brougham cart in the picture below was a purchase by Charlotte Bawden who bought it mostly because she thought the wheels were so valuable. Tom Ives (the farmer from Ives Farm at the end of their Garden) was selling it, and for some years it was kept under the trellis.

On the top of the trellis building is a wooden carved soldier made by Eric Townsend, the arms moved in the wind to scare birds on the farms.

Edward Bawden, My heart, untravel’d, fondly turns to thee (aka Derelict Cab), 1933

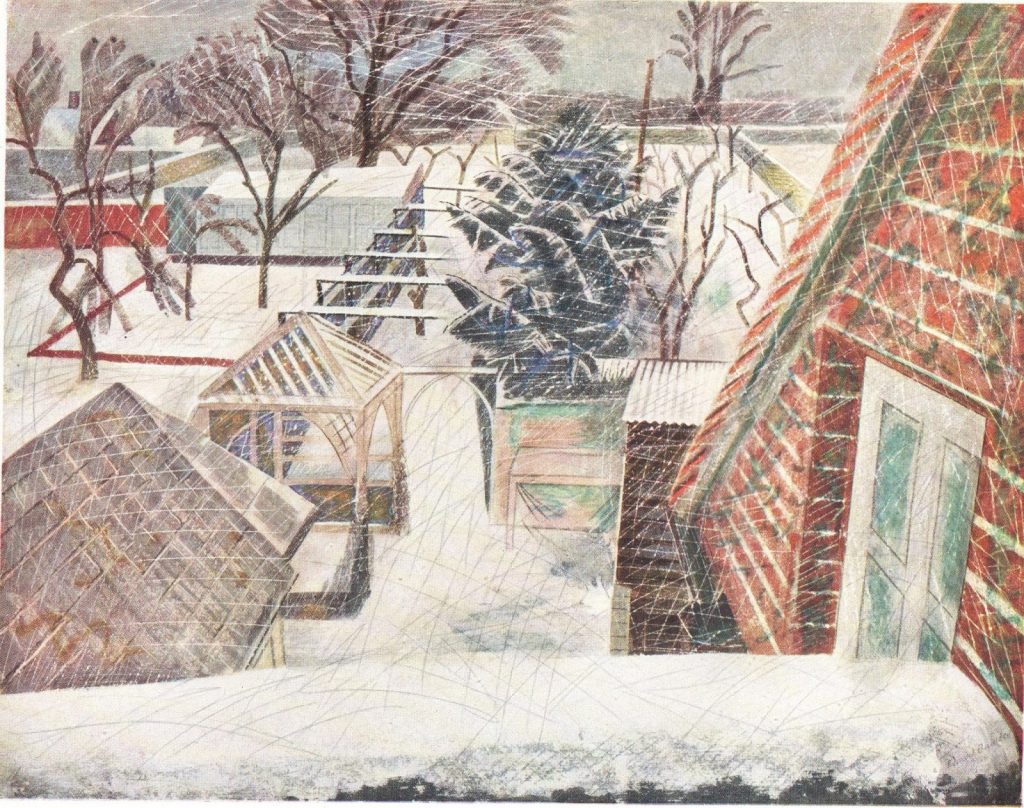

The picture below is of a Snowstorm by Bawden, he has scratched the paper to give the effect of snow blowing on the wind in all directions as it falls. The view is from the window in his Studio that looked almost right down the drain pipe. The carriage likely sold or scrapped by that point.

Edward Bawden, February 2pm, 1936

In 1937 the Country Life Cookbook had wood engravings inside, designed by Eric Ravilious and it featured a small wood engraving of the Brick House garden and the trellis again. By this time the Raviliouses had moved to Castle Hedingham, about six miles east of Great Bardfield.

Eric Ravilious – August, Wood-engraving for the Country Life Cookery Book, 1937

Below is a painting by another visitor to Brick House, Geoffrey Hamilton Rhoades. He is mentioned in Anne Ullman’s edited Tirzah Garwood biography Long Live Great Bardfield. This painting has a guessed age of c1940s, I would again say it is likely mid-to-late 1930s as the toy soldier is still on top of the trellis. The other amazing and totally unrelated detail about this painting is it was bought by Pixie O’Shaughnessy-Lorant in 1987. What an amazing name!

Geoffrey Hamilton Rhoades – Brick House, Great Bardfield, likely about 1935

During the Second World War Edward was touring the world painting as an official War Artist, Charlotte was in Cheltenham teaching and potting at Winchcombe, and their two children Richard and Joanna were at private schools in the Cotswolds. As the Brick House was empty it was used, and abused by the Home Guard and local officials as a headquarters. The house was the only building in Great Bardfield to suffer bomb damage. Many villages in the East of England were bombed, not as planned targets, but mostly from German bombers trying to dispel leftover bombs after failed bombing raids on airfields, factories or docks. The bombs being so heavy would use up more their the aircraft’s fuel and make it harder to fly back to their Nazi bases over the German Ocean.

After the War, John Aldridge painted the builders repairing Brick House. It was likely that the trellised building Eric and Tirzah gave to the Bawden’s was blown up at the same time. Eric, also an official war artist was also lost in the Second World War, in an aircraft off the coast of Iceland.

John Aldridge – Builders at Work, Brick House, Great Bardfield, 1946

John Aldridge had moved to Great Bardfield with Lucie Brown (nee Saunders) and the couple lived in sin until in 1940 John married her when he signed up to join the war effort.

The last painting of Brick House is this snow scene by Edward in 1955. Richard and Joanna are on a sledge and the roofs are covered with snow as is the ground making the red bricks bolder in colour.

Edward Bawden – Brick House, Great Bardfield, 1955

From the Plague Journal 12/07/2020

At midday from Cambridge Station I got onto one of the cleanest railway carriages I have seen in years to Liverpool Street. Being so late in the day may have been why I had the carriage to myself, and even as I travelled south through various cities, no one else joined me, it was quite luxurious, I would say there were twenty people onboard the whole train.

It was nice to sit and forget about the world, to not be in my house and to feel normal again, even with a facemask on and the perfume of alcohol hand gel. The one thing I love about travelling by train is the views, looking into peoples homes and gardens, looking in at their world and thinking that the trampoline that likely means they have children, or the various conservatories and extensions properties have had. I even enjoying seeing how the blurred scenery changes from houses to fields and then to the industrial Tottenham Hale in a series of scattered wipes.

Into a tunnel lit by white disco balls the train slides with a La Monte Young symphony of train break screams into Liverpool Street Station, the railway cathedral of Edward Bawden made of iron.

The station is now one way and the flow of traffic pulled me towards Old Spitalfields Market where I met my friends Mark and Lawrence. Lawrence runs an art stall. If you don’t know the history of the market, there has been a market on the site since 1638 when King Charles I gave a licence for flesh, fowl and roots to be sold on Spittle Fields, then a rural village. In the Victorian era was known mostly for selling fruit and vegetables. The market was acquired by the City of London Corporation in 1920, to serve as a wholesale market and in 1991 the market was in the heart of the city and made it harder to trade from, so it moved to New Spitalfields Market, Leyton, and the original site became known as Old Spitalfields Market.

On Lawrence’s art and sculpture stall was a had a painting by Fred Dewbury. It is odd how a painting catches your eye and the infatuation of owning something takes hold. I asked the price and orbited the market to think about it. Rather like my train journey in I kept seeing the painting from different angles and view points as I circled around. On the train the houses and trees were blurred as I was moving past and as people got in the way or the sides of the wooden market stalls blocked my view point I realised it was the picture looking at me. Needless to say I bought it, but it’s rare to look at anything from such different angles in London these days unless it is St Pauls.

On my train journey home the same buildings and trees past me but it had started to rain and was getting dark, the stage scenery was the same but the lighting director had gone to work. The square windows of someone’s home became Christmas lights for me, a glitter covering the towns as my train washed down the tracks like a duck on a river.

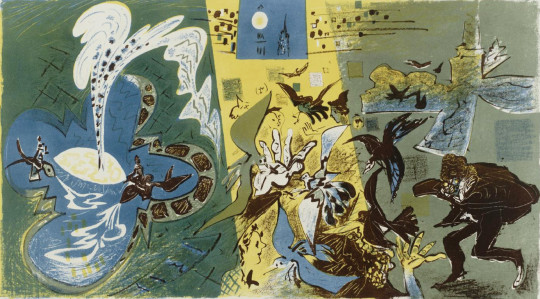

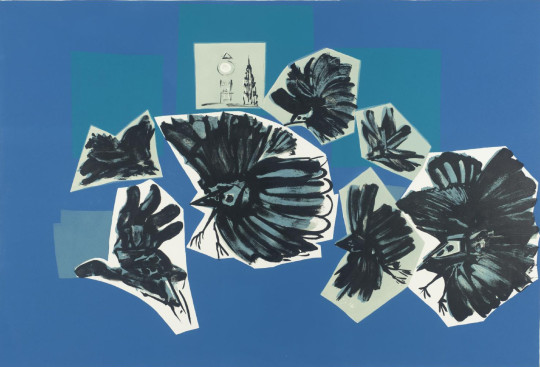

Ceri Richards painted Trafalgar Square in 1951 for the Festival of Britain exhibition 60 Paintings In ‘51. Over the next few years he would continue making prints and paintings with a series of abstractions.

He taught at various London art colleges and after 1951, when a large painting of Trafalgar Square (now in the Tate Gallery) was shown at the Festival of Britain, his reputation was international. †

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square, London, 1950

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square, 1951

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square II, 1951

After working on a series of these paintings and various drawings Richards issued the lithograph below in 1952. In another five years he would make another lithograph in 1957 and another in 1958. It was a theme that you would assume would be a year or two, but latest over a decade.

Ceri Richards – Sunlight in Trafalgar Square, 1952

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square (Movement of Pigeons), 1952

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square, 1957

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square, 1958

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square, 1962

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square (trial proof), 1962

Ceri Richards – Trafalgar Square, 1961–2

† Ralph Alan Griffiths – The City of Swansea: Challenges and Change, 1991

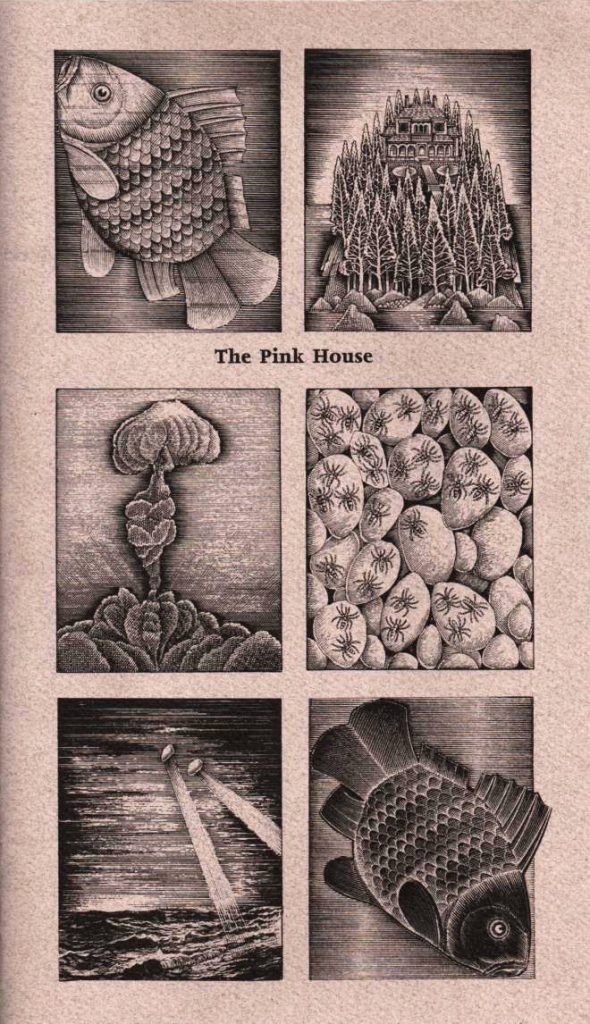

This is a short little post but a fun on about a book that was published.

Olive Cook and Edwin Smith, to those who didn’t know, were husband and wife. Edwin is famous for his photography books and Olive penned a lot of the text. They had moved to The Coach House, Windmill Hill, Saffron Walden in 1966. Originally completed in 1865, it was part of the Vineyards Estate, a large victorian house built for William Murray Tuke, the tea merchant, and designed by William Beck, a local architect in Saffron Walden who specialised in Gothic Revival.

When Olive died the old coach house was being sorted for an auction to take place outside the property with various clusters of her possessions arranged into lots inside. The papers were sorted by friends, one of whom was Philippa Pearce, author of Tom’s Midnight Garden. She found a typed up manuscript and Dennis Hall of the Inky Parrot Press assumed it was a short story Olive Cook had been due to send him.

This manuscript was typeset and printed with illustrations commissioned by John Vernon Lord.

When copies were distributed at Olive Cook’s memorial service it was recognised by Mark Haworth-Booth as a story written by his daughter, Emily Haworth-Booth, who had sent it to Olive Cook for comment.

So though the book circulates still as Olive Cook, Emily Haworth-Booth’s story was published before the Inky Parrot Press, 2002 copy; in Varsity Cherwell May Anthologies: 2001: Short Stories, 2001.

‘Olive Cook’ – The Pink House, 2002, Inky Parrot Press