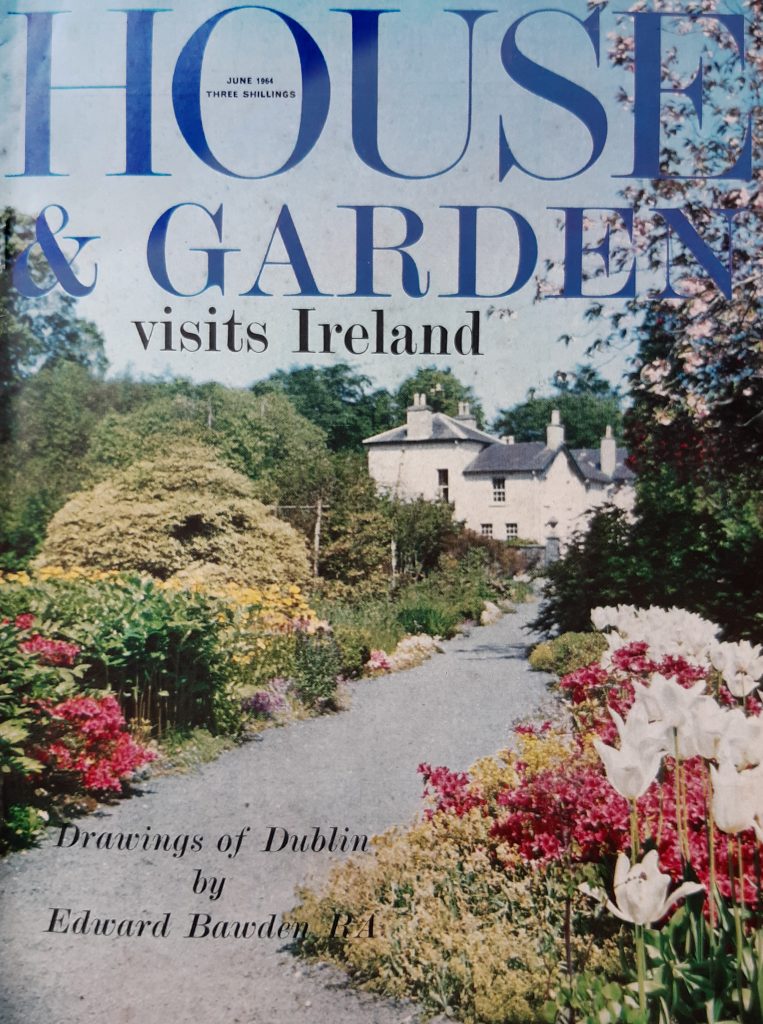

Beryl Sinclair is one of those names that I love to find. Born in 1901, Beryl Bowker was the daughter of the Dr. G. E. Bowker, a Physician at the Bath Royal United Hospital. She lived with her mother and father in Combe Park, Bath. She studied at the Royal College of Art alongside Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious.

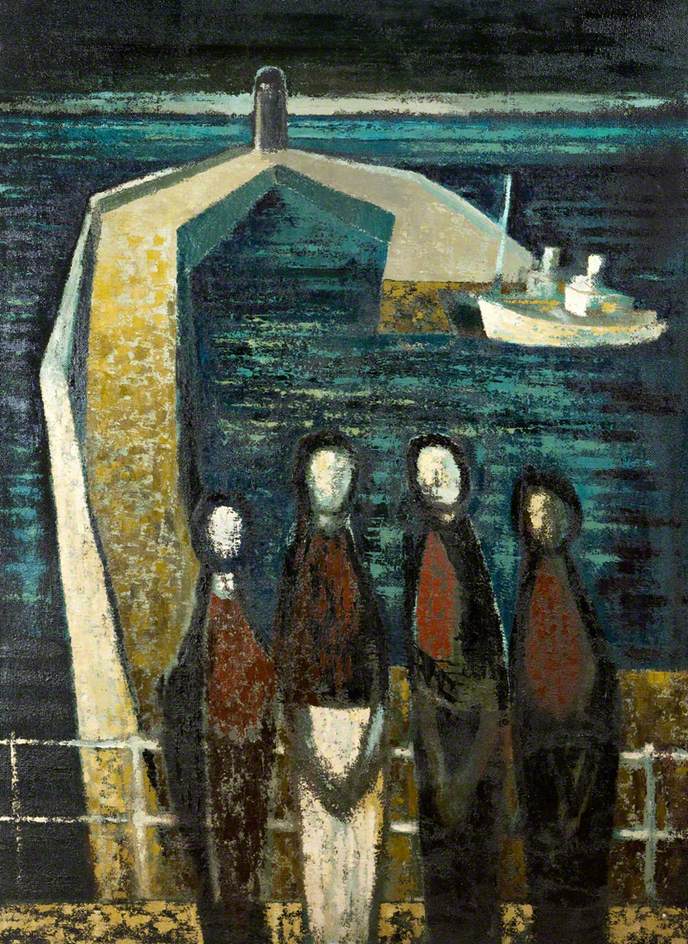

She was both a painter in oils and watercolours, as well as a potter.

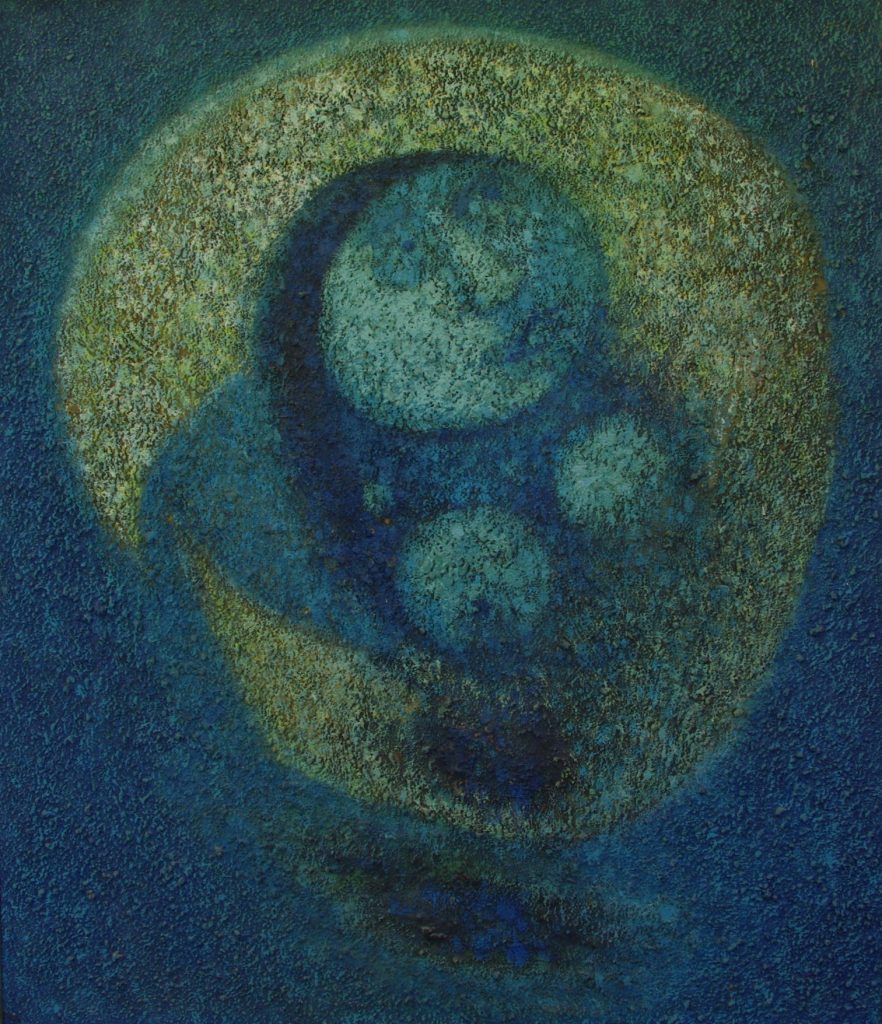

Eric Ravilious – Morley College Mural – Life in a Boarding House, 1929

At the RCA she was known as Bowk. Ravilious painted her twice that we know, once into the Colwyn Bay Pier Murals by Ravilious in the kitchen with a plant and then again in one of the ‘lost’ Ravilious oil paintings – ‘Bowk at the sink’, 1929-30.

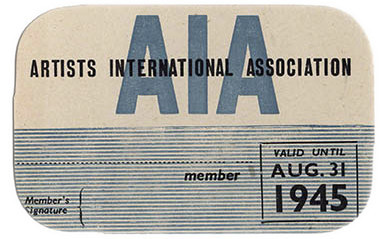

Eric Ravilious – Newhaven Harbour, 1935

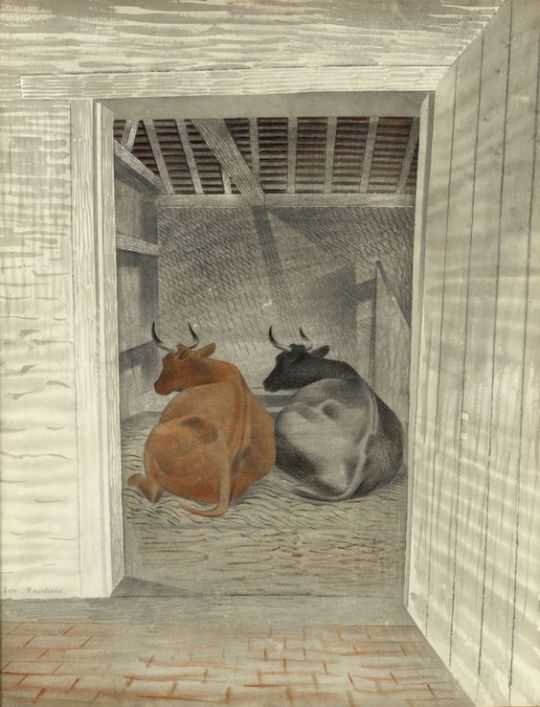

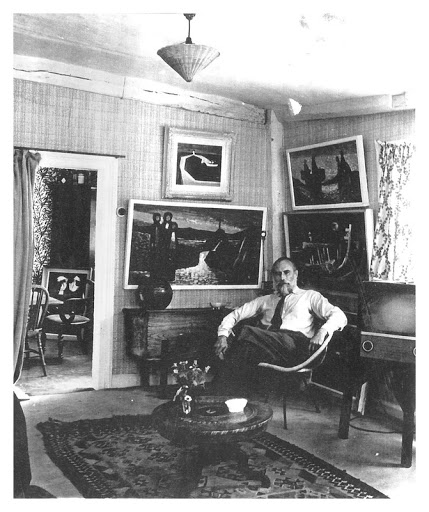

She married Robert Sinclair, a London author and journalist, who wrote the Country Book on East London in 1950. The painting above by Ravilious was bought from the Zwemmer Gallery by Beryl Sinclair.

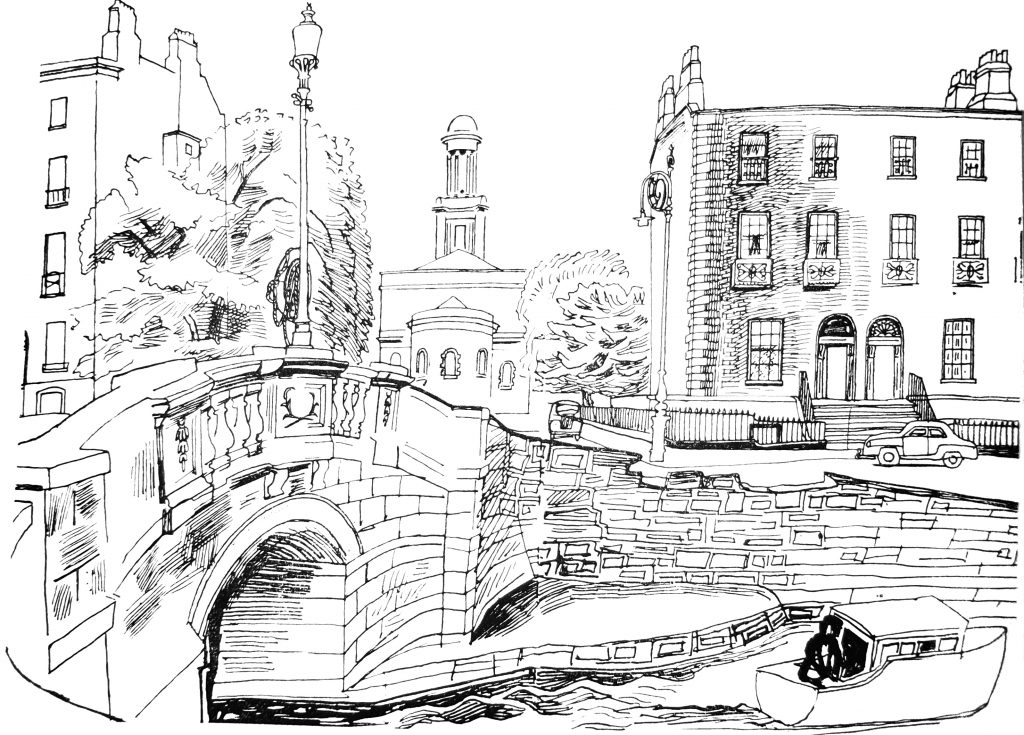

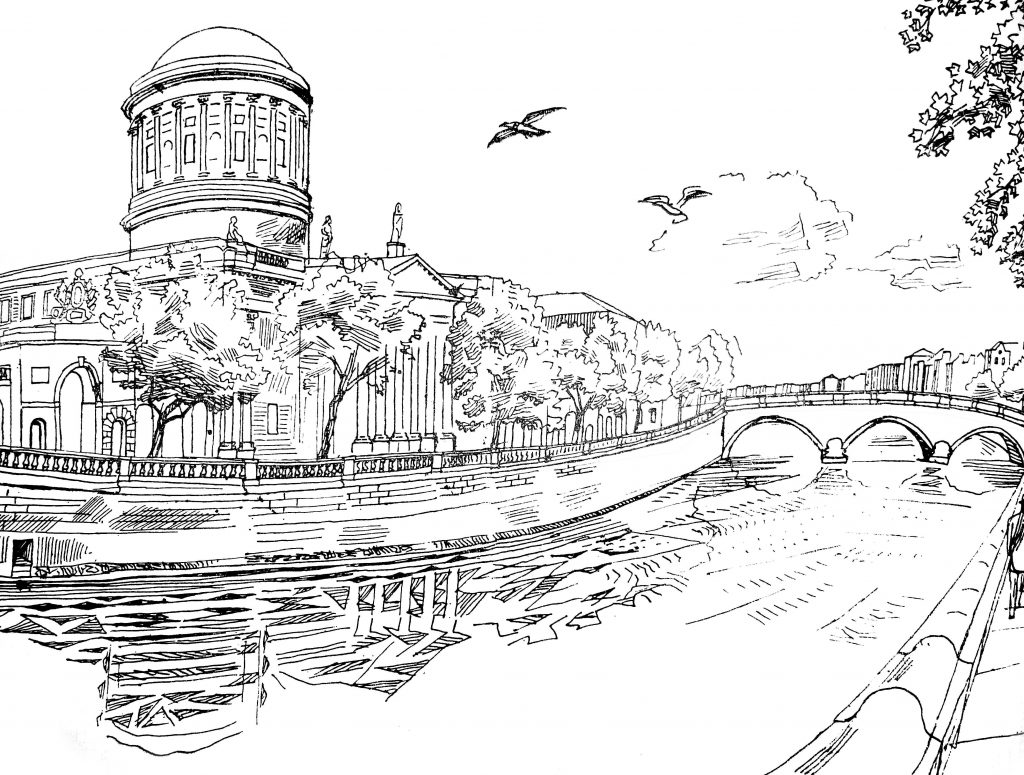

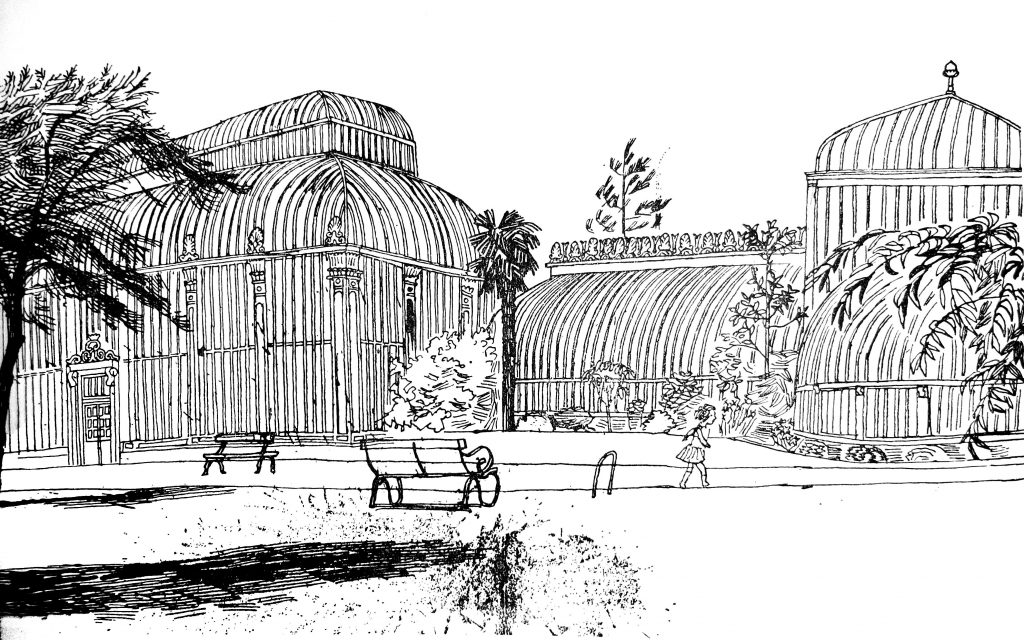

Beryl Sinclair – Regents Park, The Horseguards

They were living at 170 Gloucester Place, London. It might explain why many of her early paintings are of Regents Park as it’s less than 200 metres away.

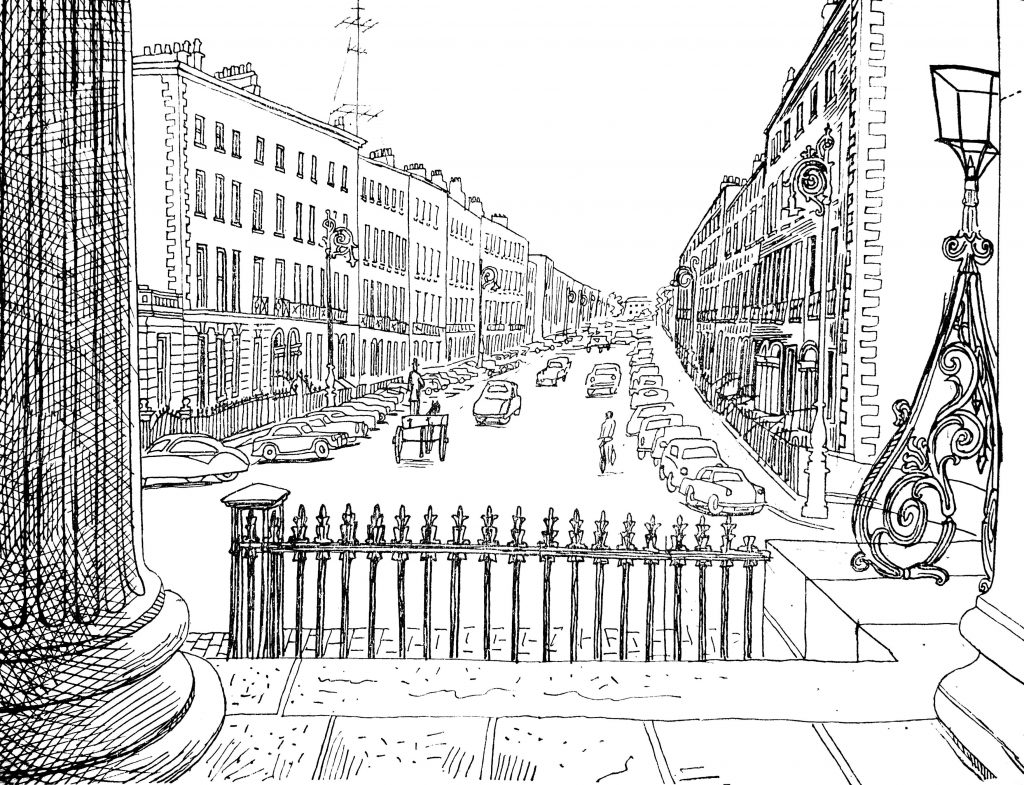

Beryl Sinclair – Regents Park, Sussex Place

In 1939 she was part of the Artists International Association – Everyman’s Print series contributing two prints, The Row and Riding Procession. The AIA Everyman Prints exhibition was opened on 30 January by Sir Kenneth Clark.

In the early 1940s she was the Chairman of the Artists International Association.

Essentially set up as a radically left political organisation, the AIA embraced all styles of art both modernist and traditional, but the core committee preferred realism. Its later aim was to promote the “Unity of Artists for Peace, Democracy and Cultural Development”. It held a series of large group exhibitions on political and social themes beginning in 1935 with an exhibition entitled Artists Against Fascism and War.

The AIA supported the left-wing Republican side in the Spanish Civil War through exhibitions and other fund-raising activities. The Association was also involved in the settling of artists displaced by the Nazi regime in Germany. Many of those linked with the Association, such as Duncan Grant were also pacifists. Another of the AIA’s aims was to promote wider access to art through travelling exhibitions and public mural paintings. ‡

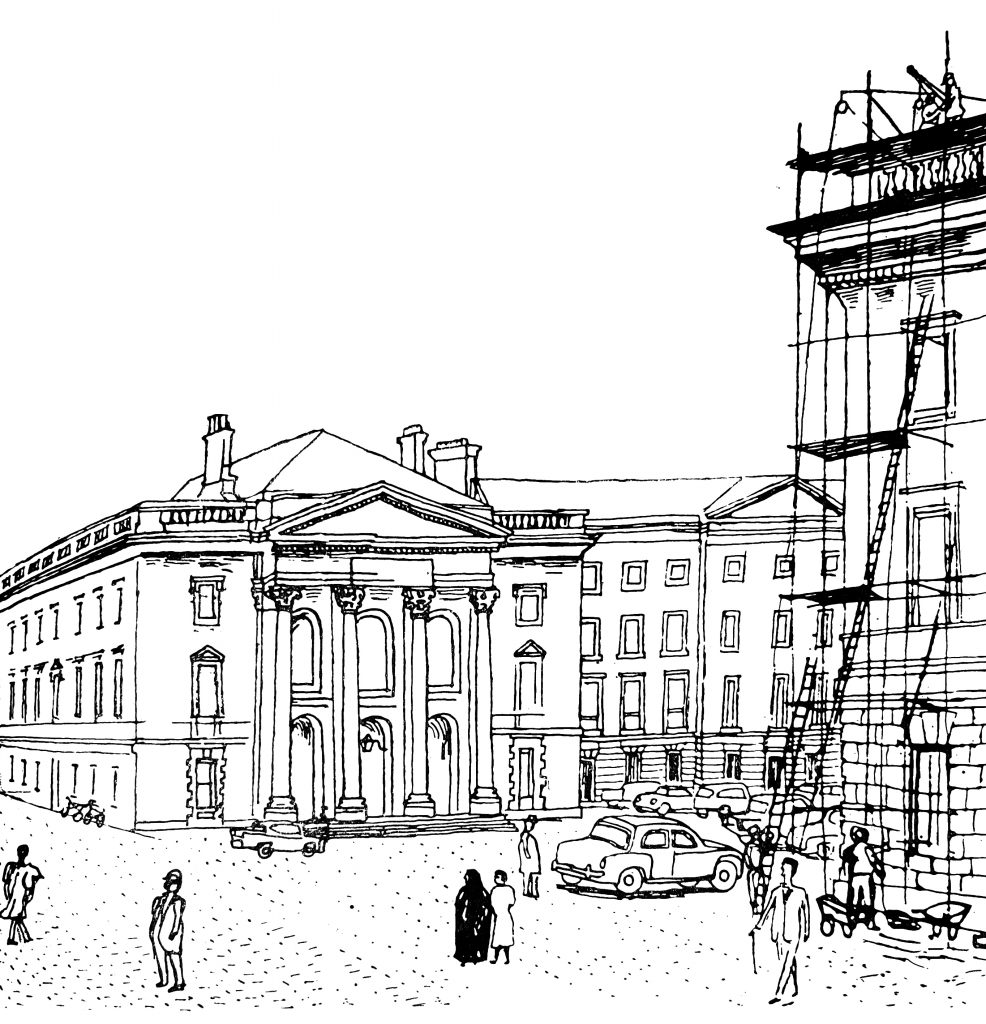

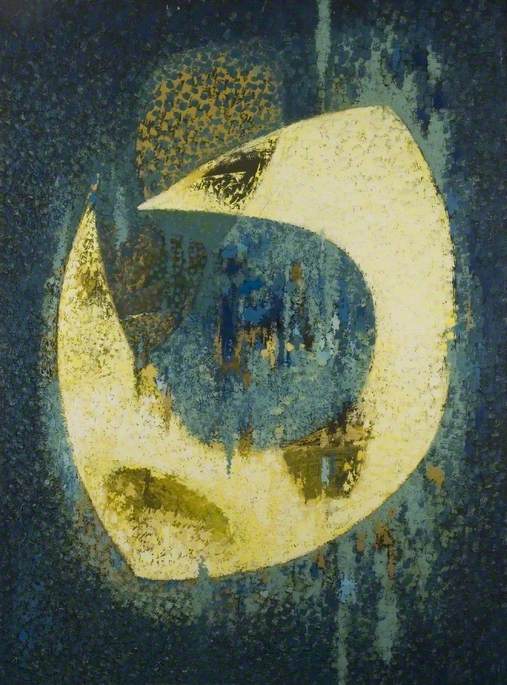

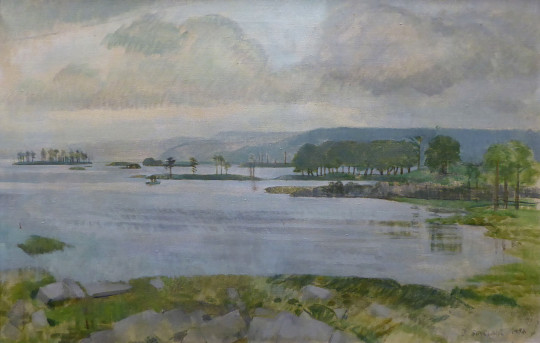

Beryl Sinclair – Lake District

In late 1940s she was the Chair of the Woman’s International Art Club. The Women’s International Art Club, briefly known as the Paris International Art Club, was founded in Paris in 1900. The club was intended to “promote contacts between women artists of all nations and to arrange exhibitions of their work”, it provided a way for women to exhibit their art work. The membership of the club was international, and there were sections in France, Greece, Holland, Italy and the United States.

During WW2 she was part of a touring exhibition of art:

John Aldridge, Michael Rothenstein, John Armstrong, Kenneth Rowntree, Beryl Sinclair, and Geoffrey Rhoades. The paintings are touring Essex. They have already been to Maldon, Colchester, and Braintree. †

She then joined the Council of Imperial Arts League in 1952 becoming the chairman in 1958.

During the war she was commissioned by Sir Kenneth Clark to execute paintings for the Civil Service canteen. She also contributed to the Cambridge Pictures for Schools scheme. She exhibited at the Royal Academy, New English Art Club, the London Group, Women’s International Art Club, Artists International Association and shows at Leicester Galleries. Her work is in the collection of the Arts Council, The British Government, The Council for the Encouragement of Music and Art, Buckinghamshire County Museum

When married she moved to White Cottage, Grimsdell’s Lane, Amersham in Buckinghamshire. She died in 1967.

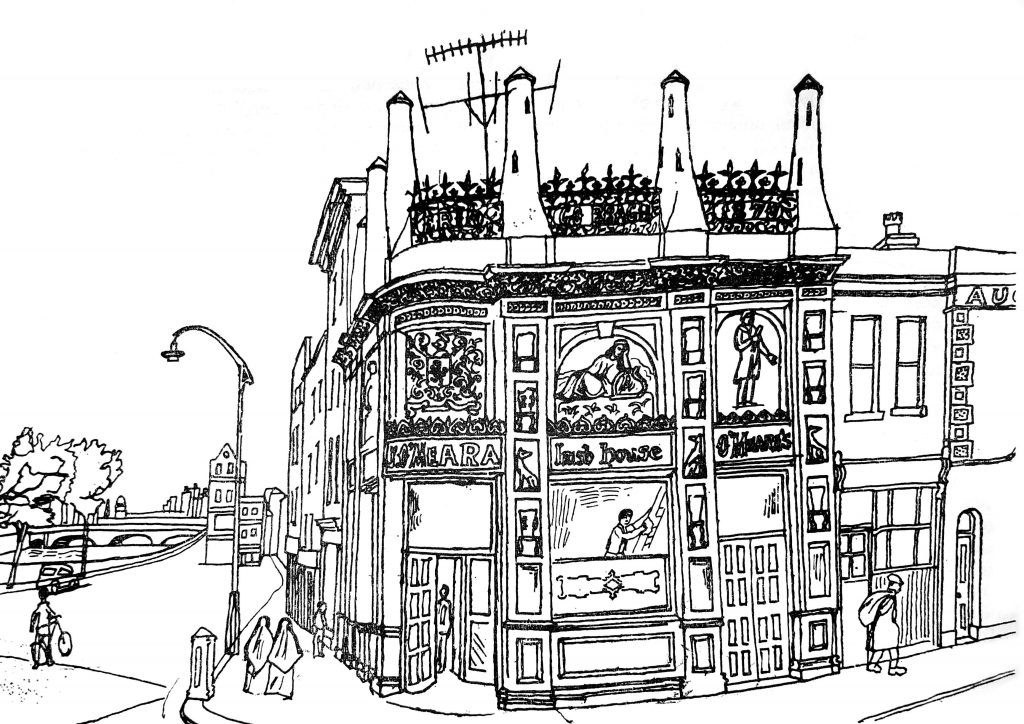

Beryl Sinclair Studio Pottery Mark.

† Chelmsford Chronicle: Friday 13 November 1942

‡ Wikipedia AIA