Below is a piece on James Ravilious, written 20 years ago in ‘World of Interiors’, March 1996 by Ronald Blythe. The pictures are the same as in the magazine.

I was inspired to type it up after having gone to see a show of James Ravilious’s works at the Fry Gallery, running from 18th June – 24th July (2016). The exhibition’s booklet has a quote by Olive Cook from Matrix Magazine #18: "I know of no other presentation of a particular place and people which is as broad and as captivating as James Ravilious’s photographs of North Devon. They are the fruit of a quite exceptional acuity and patience of witness and of a quite unusual humility and warmth of spirit. This great body of work establishes its author as a master of the art of photography whilst at the same time it makes an unparalleled pictorial contribution to social history.“

James Ravilious – Young Bulls eating Thistles

Plainly Pastoral – James Ravilious. World of Interiors. March 1996.

For over 20 years photographer James Ravilious has captured on camera powerfully candid images of rural North Devon life for the Beaford Archive. A Corner of England, a new book of his pictures, is full of ‘private moments’ photographed without pathos.

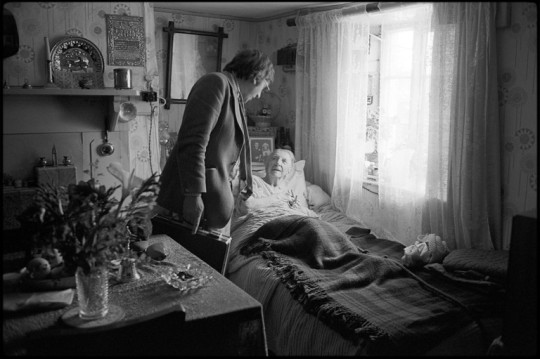

This second collection of James Ravilious’s work has to be studied for three distinct reasons. Because it is in the great tradition of Henri Cartier-Bresson, because it corrects our distorted vision the English countryside, and because it reveals the poetry of the commonplace. In 1973 Ravilious was invited to restore and add to the Beaford Archive, a remarkable library of photographs of village life in North Devon. This wonderful book shows him way ahead of his commission. His Leica records his own intimacy with the region, its landscape, its people, its creatures. No ordinary journalist or social historian could have gained

Ravilious’s entree to these extraordinarily private rooms and fields, or be taught to see what he so naturally sees.

James Ravilious – ‘Dr Paul Bangay visiting a patient, Langtree, Devon 1981

The book’s pictures have been drawn from his own contribution to the Beaford Archive and he describes them as ‘rather like scenes from a tapestry I have been stitching over the years’. His wife Robin, a local girl, contributes a few hard facts. ‘The small mixed farm is the commonest unit still. Short of labour, short of capital, bothered by paperwork and recession, farmers struggle stoically in a cold soil, high rainfall and awkward upland terrain…’

James Ravilious – Pigs and woodpile, Parsonage Farm

Ravilious’s camera scrupulously avoids wringing the usual bitter-sweet agricultural drama out of this situation and his work is masterly in its absence of comment.He has a way of capturing a private moment without making it public, so to speak. So the reader/looker has to share his intimate views if they are to see anything at all. As one stares into these twisting lanes, farmyards, churchyards, bedrooms, kitchens, animals’ faces, sheds, shops, schools, one often feels apologetic at invading something so personal, then grateful for having been shown what is actual, true and good.

James Ravilious – Red Devon cow, Narracott, Hollocombe, Devon, England, 1981

This is a rural world without ‘characters’, only people. Not even the old tramp sunning himself amidst the rubbish tip of his belongings is a character – just a naked man on the earth. Nor do the farm animals set out to beguile but are captured without sentiment. A snowdrift of geese on a darkening hilltop and a dog on a blackening road are waiting for the first thunderclap. A sick ram rides home in a tin bath. Here is the ordinariness of the harsh and lovely pastoral. The Ravilious ‘interior’, whether of houses or hills, can shock or inspire- usually both. A rare country book. – Ronald Blythe.

James Ravilious –

Storm Clouds with Geese

– ‘A Corner of England: North Devon Landscapes and People’ by James Ravilious. Lutterworth Press.