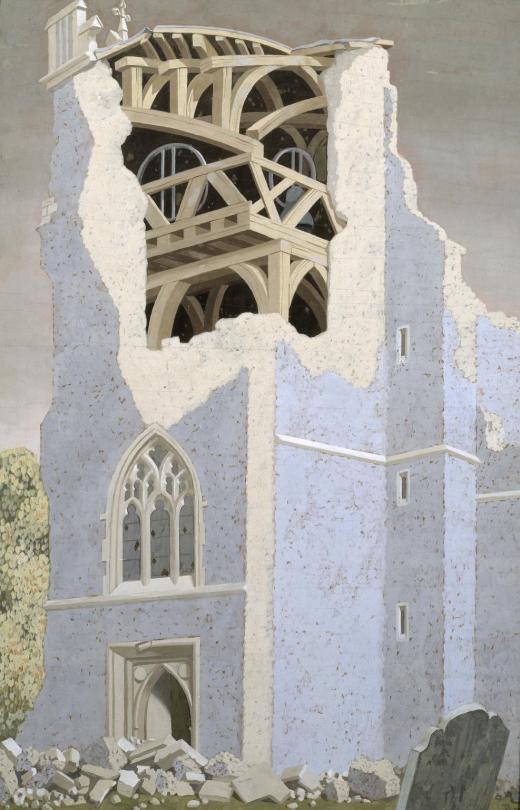

John Armstrong – Coggeshall Church, Essex, 1940 – Tate – Not on Display

When most people think of artists and where they paint – they think of St

Ives, Cornwall. The new Tate gallery there and its controversial Stirling Prize nominated extension have been both a help and hindrance to locals, but maybe not the 24% of those in St Ives who are Second Home owners †. The same could be said for Margate and the Bilbao effect from the Turner Contemporary Tate Gallery there. The Tate has pushed tourist through Margate’s streets like air into lungs. In the East of England is where many of the country’s best loved artists lived, but sadly the East of England is rather poor when it comes to showing off their artists – so why not a branch of the Tate in Aldeburgh or Southwold or Colchester?

John Constable – Stoke-by-Nayland, 1811 – Tate – Not on Display

The famous East Anglian artists of old are John Crome, Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable. Crome was the most famous of the Norwich School of painters who were inspired by painters like Jacob van Ruisdael and the Dutch style. They painted the vast waterways, windmills and dykes of the fenland and Norfolk Broads. Crome also had many talented pupils. John Sell Cotman, one of the country’s best watercolour artists, was also part of this brew.

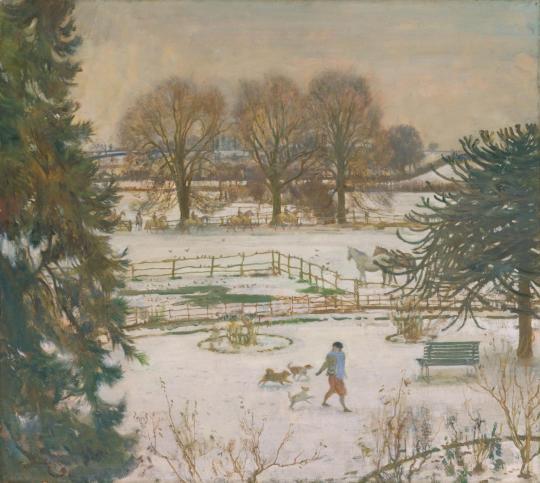

Alfred Munnings – From My Bedroom Window, 1930 – Tate, Not on Display

John Constable painted the Dedham Vale in Suffolk and, most famously, Flatford Mill. A brisk walk away is the Museum and former home of Alfred Munnings. Also in Dedham was the original home of Cedric Morris’s East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing, but when it burnt down (John Nash told Ronald Blythe ‡) Munnings drove around the village like Mr Toad shouting ‘Down with modern art’. Cedric Morris then bought Benton End from Alfred Sainsbury in 1939 and continued his art school with his life partner, Arthur Lett-Haines. Lucien Freud, Maggi Hambling, Lucy Harwood, Valerie Thornton and Olive Cook all studied there.

Cedric Morris – Iris Seedlings, 1943 – Tate – Not on Display

In 1940 after his London home suffered bomb damage, the sculptor Henry Moore made his home in Perry Green, just south of Much Hadham. It is now a museum with a collection of his works in the grounds. Moore walked around the local fields picking up pieces of flint thrown aside from ploughing and in his studio he would draw them as pre-made organic sculpture. Moore called them his ‘library of natural forms’ and they would inspire his larger works.

Henry Moore – Seated Woman, 1957 – Tate – Not On Display

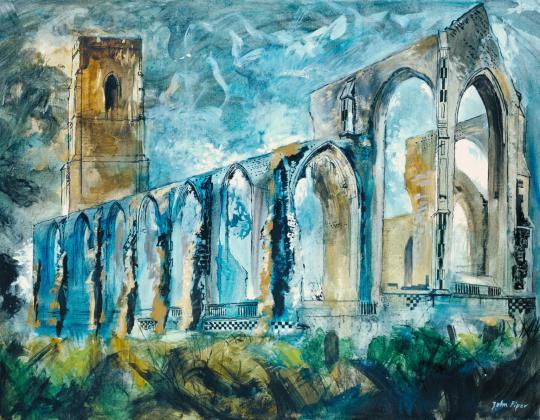

John Piper in the 80s made a beautiful series of ruined churches of East Anglia. In 1934, at Ivon Hitchens cottage in Sizewell, Suffolk, Piper met his wife Myfanwy Evens. They married in 1937. Myfanwy worked with Benjamin Britten writing lyrics to his operas including Death in Venice. Britten lived in Aldeburgh with his partner Peter Pears. Piper would design many of the stage sets.

John Piper – Covehithe Church, 1983 – Tate – Not On Display

On the other side of Colchester in 1944, war artist John Nash was restoring the Elizabethan Bottengoms Farm, moving in with his wife Christine Kühlenthal. Christine had studied at the Slade school of art alongside Dora Carrington, Mark Gertler and she worked at the Omega Workshops while John had become famous for his monumental paintings of the First World War alongside his brother Paul. At Bottengoms, John became famous for his landscape paintings and botanical studies. He taught at Colchester School of Art with Richard ‘Dickie’ Chopping, an artist known for his dust jackets for Ian Fleming’s James Bond series. Dickie lived with his lover, another landscape painter, Denis Wirth-Miller. Their life with Francis Bacon has been expertly documented in Jon Lys Turner’s ‘The Visitors’ Book’. Bacon owned a home in Wivenhoe as did Dickie and Denis.

John Nash – Mill Building, Boxted, 1962 – Tate – Not On Display

Also on the staff at Colchester was John o’Connor, a wood-engraver and landscape painter. He was once the pupil of both Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious at the Royal College of Art. Bawden and Ravilious where renting part of Brick House in Great Bardfield, Essex, when Ravilious moved a few miles away to Castle Hedingham with his painter wife Tirzah. Bawden and his Leach Pottery student wife Charlotte bought Brick House. Both men became war artists and only Bawden returned from the conflict after painting the early war, including Dunkirk. He was also shipwrecked off the coast of Africa, rescued and imprisoned by Vichy French forces, liberated by the Americans and then off again to paint the campaigns in Africa and Iraq. Eric died in 1942 when the aircraft he was in was lost off Iceland. Ravilious used the Essex area profusely in his short life there in

wood-engravings and watercolours.

Eric Ravilious – Tiger Moth, 1942 – Tate – Not on Display

Around the village of Great Bardfield, Bawden was joined by John Aldridge (a landscape painter), Walter Hoyle (one of Bawden’s students who helped Bawden on work at the Festival of Britain) and Michael Rothenstein (the pioneer printmaker and brother to the Director of the Tate Gallery). Other artists in the village were George Chapman, Bernard Cheese, Stanley Clifford-Smith, Audrey Cruddas, Sheila Robinson and Kenneth Rowntree.

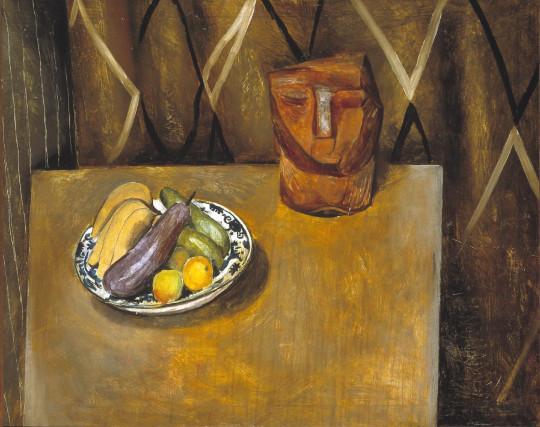

John Aldridge – Head and Fruit, 1930 – Tate – Not on Display

In the small hamlet of Landermere – on the coastland of Essex – lived Adrian and Karin Stephen with their daughter Judith. Adrian was the younger brother of Virginia Wolfe and Vanessa Bell. After her parents death Judith lived on in their house with her husband and Independent Group member, Nigel Henderson. Also in Landermere they were joined by Eduardo Paolozzi who owned one of the cottages and set up Hammer Prints Limited, a company for printing limited edition works and designing abstract home wares such as wallpapers and tiles. Neighbours in the hamlet were architect Basil Spence and Festival of Britain artist and Coventry Cathedral glass engraver, John Hutton, as well as his son, children’s book illustrator Warwick.

Eduardo Paolozzi – Cyclops, 1957 – Tate – Not on Display

The Stephens were not the only Bloomsbury members to be in the East. David Garnett, his lover Duncan Grant, and Grants wife Vanessa Bell were all staying at Wissett Lodge, Suffolk in the summer of 1916 as conscientious objectors, working on a farm, though Vanessa is the one who got the most painting done.

With the boom in British publishing many of these artists enjoyed illustration commissions, from the cookery books of Ravilious and Bawden to poetry books decorated by John Piper and gardening books illustrated by John Nash.

Spencer Gore – The Beanfield, Letchworth, 1912 – Tate – Not On Display

Naturally there are names left out but there are too many artists to list. But why are they so poorly represented in the region? In the East there is the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts and Kettles Yard but neither of these galleries aim to promote the work of East Anglian artists, but rather the international collections of the Sainsbury family and Jim Ede. They both do a lot of good for the local economy but it’s not the same as championing the area’s artists.

The nearest to it is the Fry Art Gallery in Saffron Walden, but their manifesto only lets them collect work from artists who have lived in North West part of Essex. But for all of Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Norfolk and Suffolk there should be a body to represent them.

There are so many other artists that could be liberated from the Tate and their archives and put on show to support and promote the region where they were created. At the time of publishing, all the artworks in this blog owned by the Tate were not on display.

† https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/cornwall-second-homes-plague-revealed-1398388

‡ A Broad Canvas – Ian Collins 1999 – From the Foward by Ronald

Blythe, p6.