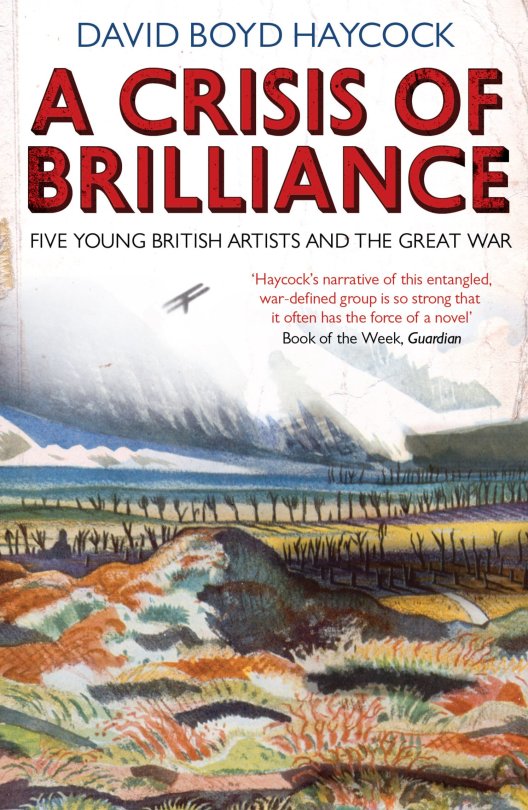

Last summer I was reading ‘A Crisis of Brilliance’ by David Boyd Haycock, it is a wonderful layer-cake of young artists lives as they study at the Slade School of Art on the eve of the First World War and a book I recommend to all to read.

Many of the artists featured are supported by a patron, Eddie Marsh, who not only bought their work but he entertained them and introduced them to people in society who would advance their careers.

Marsh was a strange and unique person. In his career as a civil servant he worked as Private Secretary to a succession of Great Britain’s most powerful ministers, particularly Winston Churchill.

He was the sponsor of the Georgian school of poets and a friend to many poets, including Rupert Brooke and Siegfried Sassoon. He was a discreet but influential figure within Britain’s homosexual community.

Matthew Smith – Woman Reclining, c.1925–6

Some of the money Marsh had to spend on art was the remainder of a family legacy from the death of his great-grandfather, Spencer Perceval in 1812, the only British prime minister to have been assassinated. Parliament voted to settle £50,000 on Perceval’s children (today it would be around 8 million), with additional annuities for his widow and eldest son. 100 years later and Marsh was using the money to buy art.

Although Spencer Perceval possessed six sons and six daughters, some portion of this grant drifted down to Eddie Marsh through his mother. He refused to use any of what he called ‘the murder money’ for his personal requirements; it was from this fund that he bought, with taste and knowledge, the collections with which he has now enriched the public. †

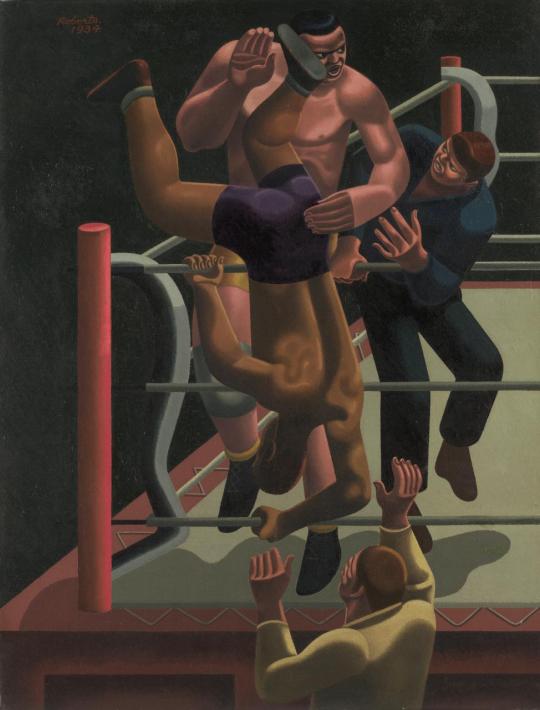

William Roberts – Sam Rabin vs Black Eagle, 1934

After Marsh’s death in 1953 his friends collected accounts of him and published a booklet, edited by Christopher Hassall and Denis Mathews. As it is long out of publication, I have typed up John Rothenstein’s piece on Marsh’s art collecting below. All the pictures in this post were owned by Marsh.

Mark Gertler – Agapanthus, 1914

John Rothenstein on Eddie Marsh

There is a serious disadvantage to an upbringing in an artist’s household. Paintings, drawings, sculpture are apt to be so ubiquitous that they may fail to excite. My father being a painter and also a collector, it seemed to me in my early years that works of art were for the most part little more than part of the furnishing of our house. It is true, however, that when I visited other houses and found dull pictures on the walls or none at all, I was aware of an almost piercing sense of bleakness. But when I first visited Eddie Marsh’s chambers at Gray’s Inn, it was with no sense of bleakness but with the consciousness of something amounting almost to a new experience that I looked at his pictures.

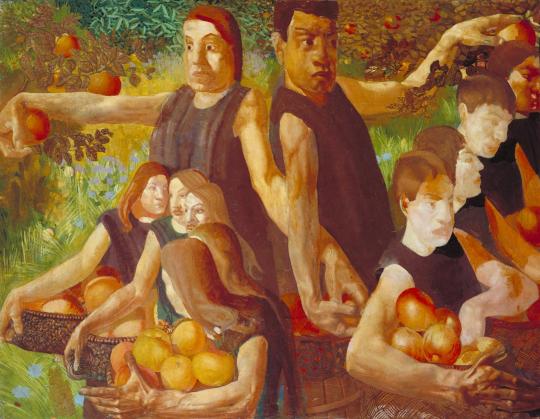

Stanley Spencer – Apple Gatherers, 1912-13

I had not come to look at his pictures; I don’t suppose I was aware that he possessed any. Like many other young men I had come, either shortly before or after leaving Oxford, to consult this benevolent oracle about the perplexing problem of how best to spend my life. I can’t recall any word of advice he gave; but I do recall, almost as clearly as though it were yesterday, the immediate fascination exercised by the pictures which hung, frame to frame, from floor to ceiling, covering every vertical space, not only of wall but of door, and, no less clearly, the kindness with which Eddie responded to the interest his pictures stirred in me. We looked at everything there was to see. And what things there were! Wilson’s Summit of Cader Idris (his bequest of which to the National Gallery, he said, lent an added pleasure to his visits there, that of choosing the place where his ghost would see it on the walls) and Blake’s Har and Heva batbing.

Richard Wilson – Cader Idris, 1774 (Exhibited)

But it was the contemporaries that gave me the sharpest and most pleasurable shock: the works of painters with whom I already had some acquaintance. There were the splendid Self Portrait and the The Apple-gathers by Stanley Spencer (an artist who had not yet held an exhibition), The Dancer: and Parrot Tulip’s by Duncan Grant, The Cornfeild by John Nash, a water-colour of tall trees by his brother Paul, and a lamp-lit bedroom by Gertler.

John Nash – The Cornfield, 1918

The spectacle of so many line examples of the work of an emerging generation of painters, displayed with such affectionate, admiring confidence strengthened the impression I had that there was a school of painting in England deserving of much more respect than most of my contemporaries were inclined to accord to it.

Henry Moore – Woman Seated with Hands Clasped, 1929

My visit was followed by several others, but it was not until many years later that I came to know him well, when I had the good fortune to be associated with him in the running of two institutions particularly dear to him: the Tate Gallery, of which he was a Trustee from 1937 until 1944 and Acting Chairman during 1940 and 1941, and the Contemporary Art Society, of which he was Chairman from 1937 until 1952.

Duncan Grant – Parrot Tulips, 1911

What made this association particularly delightful for those who had a part in it was Eddie’s attitude towards these two institutions. For him the Tate and the Contemporary Art Society were never primarily institutions at all; they were friends to be fought for, to be enriched by his generosity and, from time to.time, to be gently chided. And as such they responded to his friendship with gratitude and affection.

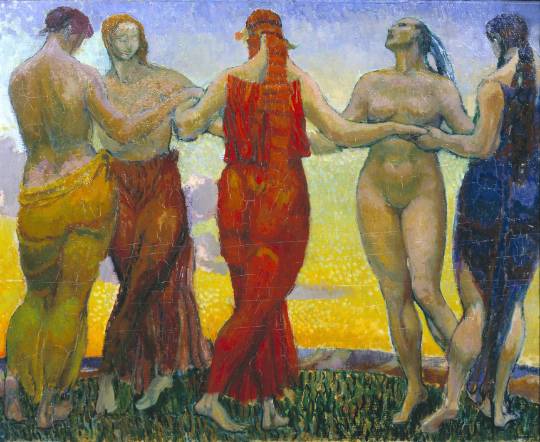

Duncan Grant – The Dancers, 1911

Eddie was not only loved at both the Tate and the Contemporary Art Society, but he reposed in them a special degree and quality of trust. He was capable of a catholicity of taste that at moments provoked his friends to wonder whether there was any work of art which he didn’t like. In his heart, however, he remained faithful to the artists the Spencer and the Nash brothers, Grant, Gertler, and their contemporaries who had first aroused in him the lust of possession.

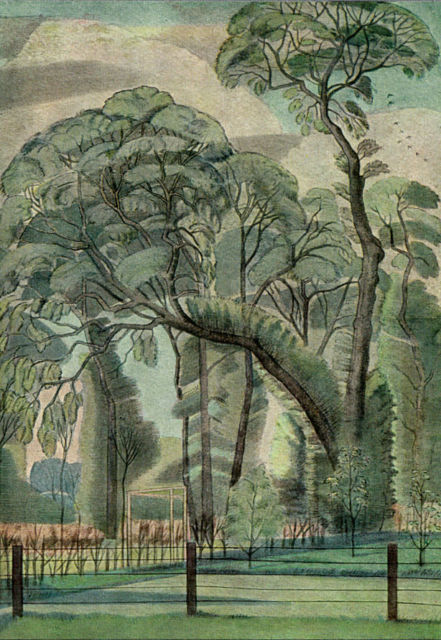

Paul Nash – Elms, 1914

The works of later painters he often, as he confessed, ‘took great though often in efficacious pains to understand and enjoy’; yet he never expected art to be changeless, and he desired the Tate and the Contemporary Art Society to collect in accordance with their most imperative convictions, whether or not these happened to conform to his own.

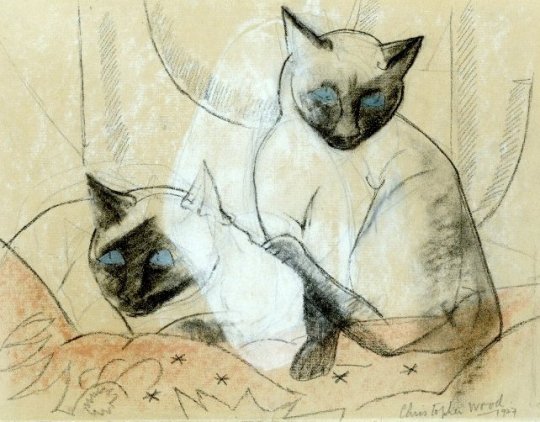

Christopher Wood – Siamese Cats, 1927

The last time I saw him, on is December 1952 at the last meeting of the Society’s Executive which he attended, it had been resolved, as a tribute to his unique services, to commission a portrait of him by Graham Sutherland.

A message from the artist was read out willingly accepting the commission but regretting that he could not undertake it until the autumn of 1953. In a voice that arrested by its intense melancholy Eddie exclaimed, ‘The sands are running out’. In the silence that followed could be read his friends’ mournful recognition that he had spoken the truth. Four weeks later he was dead.

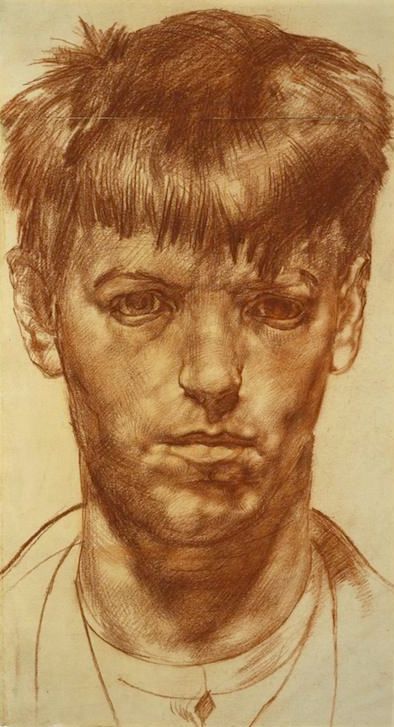

Stanley Spencer – Self Portrait, 1912

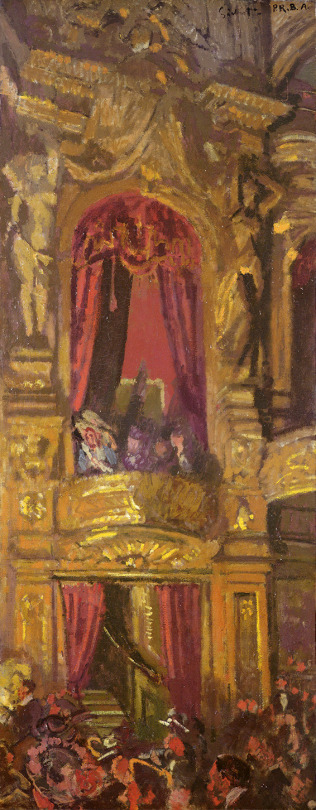

Walter Sickert – The New Bedford, 1915.

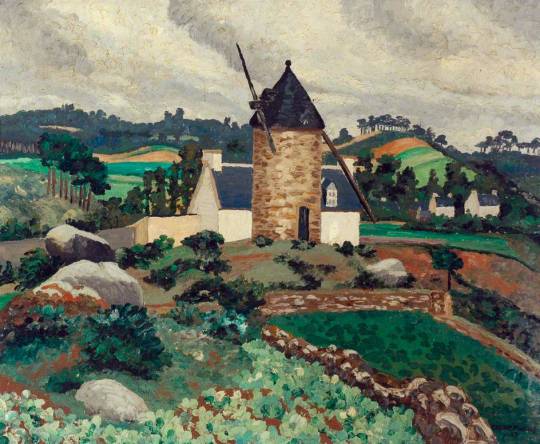

Cedric Morris – Breton Landscape,1927

Eric Ravilious – The Yellow Funnel, 1938

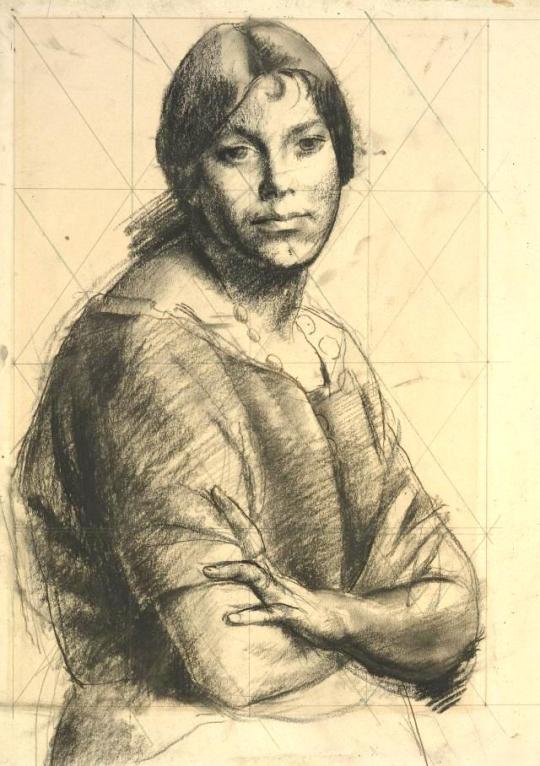

Walter Monnington – Study of a Woman, 1934

Eddie Marsh – Sketches for a composite literary portrait of Sir Edward Marsh, Lund Humphries, 1953

† Paintings and Drawings from the Sir Edward Marsh Collection, The Contemporary Art Society 1953