Suzanne Cooper – The Busman’s Holiday

To discover a new work or artist is always exciting, but it must be rather perplexing to some people who have lived with artists and their work, and over time find it admired. This happens many times with families accepting works of art on walls, but not enquiring.

A famous example of this is Evelyn Dunbar. She had died in 1960. Her work and her studio was packed up and distributed about the family soon after. In 2013 the wife of Evelyn’s nephew was watching Antiques Roadshow and saw the expert value one of her paintings at £40,000 – £60,000. Members of the family started to look for the works!

They turned out to include more than 500 paintings and drawings by Evelyn. Another nephew had been tracking the contents of Evelyn’s “lost studio”, dismantled after her death, with its contents sold on or given away to family and friends, and compiling a record of her paintings; the find doubled the number of her known works ♥

With the help of a commercial gallery the works were costed at a market price and presented to the public to buy, along with a major retrospective of these new works. A PR Video on Dunbar can be found here.

In the case of Suzanne Cooper, the family knew of the works but sought for recognition for her. They have also reprinted some of her woodblocks for sale. Her family own 14 of her paintings and various woodblocks and the original blocks, 1 painting is in the Auckland Art Gallery in New Zealand, but around 12 works are ‘lost’ and yet to resurface in the market.

Born in 1916, Cooper grew up in Frinton, Essex, the town with the reputation. We know that she was educated at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art in London under Iain Macnab and Cyril Power.

Based in 33 Warwick Square, Pimlico, London, the Grosvenor School was housed in a mansion built in 1859 by architect George Morgan for James Rannie Swinton, the Scottish portrait painter. In 1924 the house was sold following the divorce of Lady Patricia Ellison (of Louisville, Kentucky) and Sir Charles Ross (of Balnagown).

Iain Macnab married Helen Wingrave, a famous dancer and dance instructress. Macnab used some of the building as teaching rooms for his Grosvenor School and others are living quarters while his wife operated a dance studio and gave private lessons from the ball room.

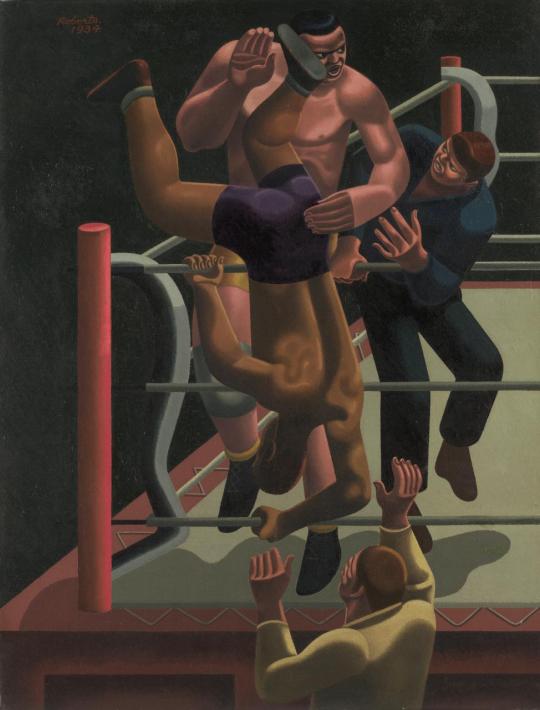

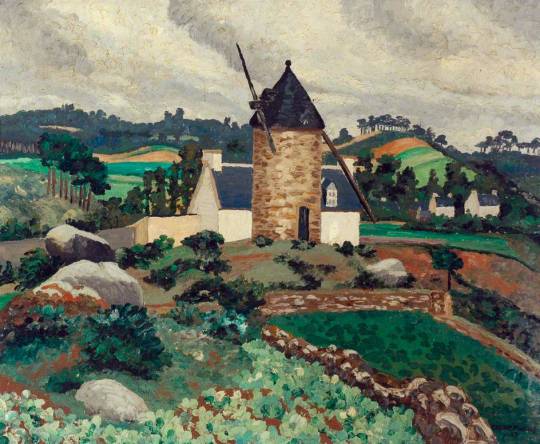

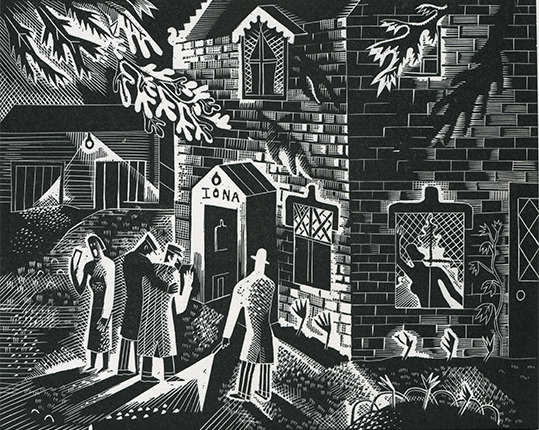

The Grosvenor School would have been the hippest place to be taught at the time and the printmaking department was having a renascence of modernism with lino and woodcuts. It is clear that Cooper was influenced by Macnab’s style in woodcut.

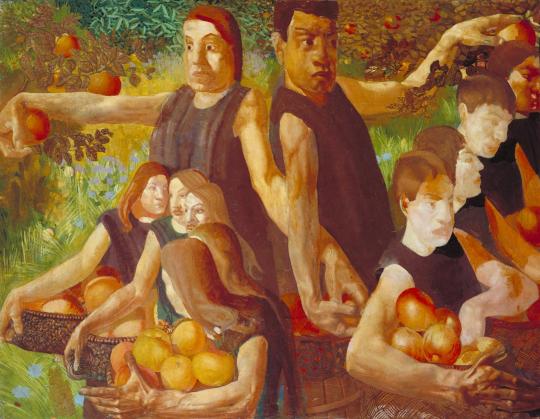

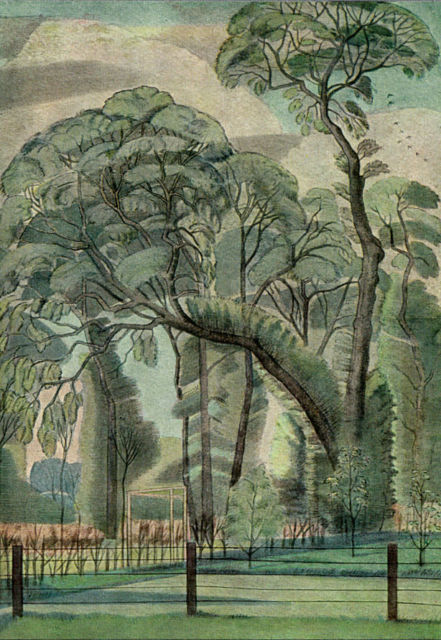

Suzanne Cooper – Back Gardens

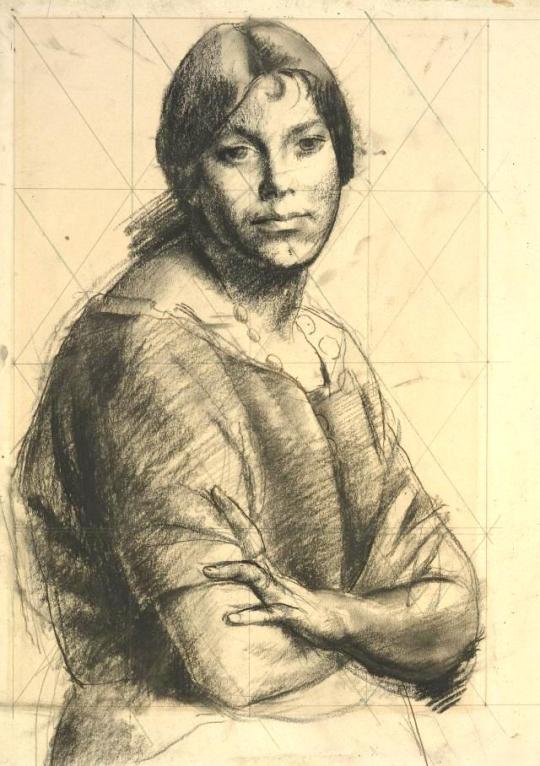

Iain Macnab – Cassis-sur-Mer

During Cooper’s time as a student she exhibited paintings and wood-engravings at the Redfern, Zwemmer, Wertheim and Stafford Galleries, mostly as part of the Society of Women Artists and the

National Society of Painters, Sculptors and Print-Makers, the later being reviewed below in 1938.

I liked the prints of Rachel Roberts, a newcomer to these exhibitions, and also those by Suzanne Cooper, Eric King, Joar Hyde, and John O’Connor. †

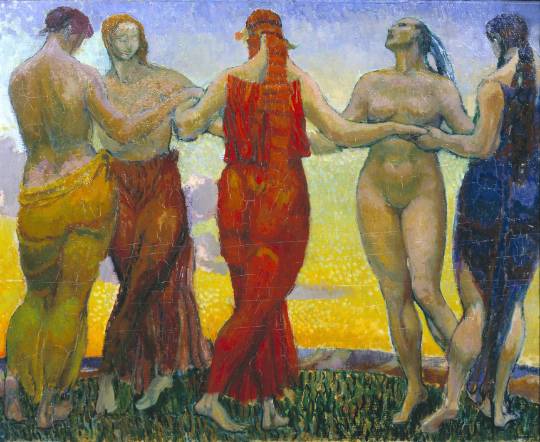

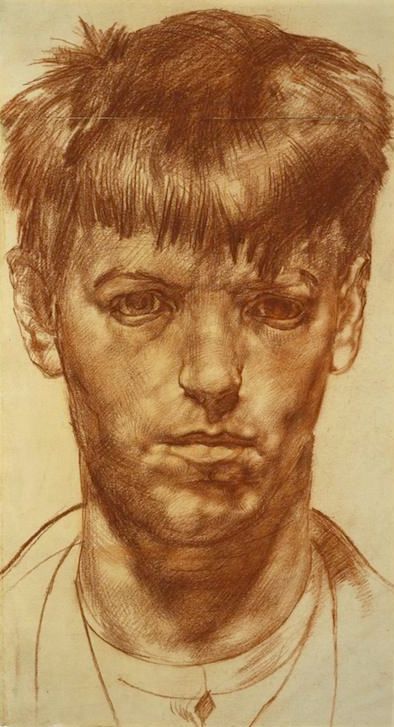

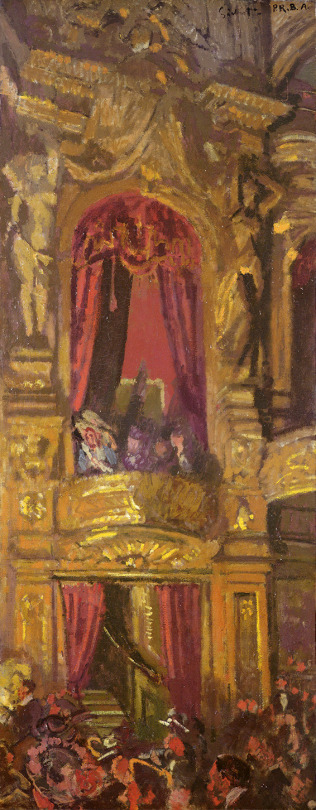

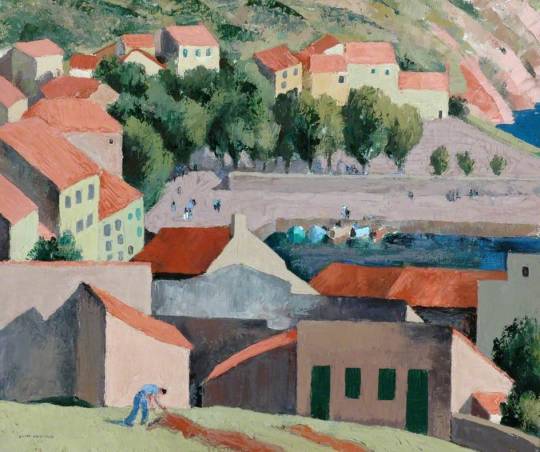

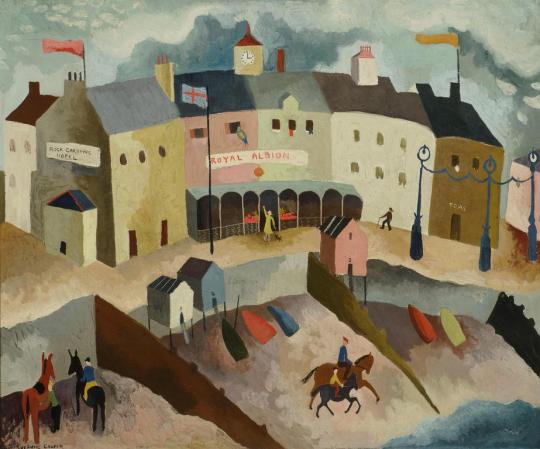

Christopher Wood’s patron, Lucy Carrington Wertheim bought one of Coopers paintings Royal Albion, she later donated it to the Auckland Art Gallery in 1948. It was at this time that Cooper was painting in oils and her work mirrored Christopher Woods in tone and composition.

Suzanne Cooper – Royal Albion, 1936

Suzanne Cooper was one of many artists who were taken under the wing of Lucy Carrington Wertheim, who was first encouraged by Frances Hodgkins to set up a modern art gallery. This delightful depiction of the Royal Albion hotel shows a common seaside view, with small boats drawn up on the beach opposite, in the protection of the groynes which can be found on many British beaches. The artist’s use of simplified blocks of form and colour was popular with members of the St Ives school of painters. ‡

The fashionable appeal of the Grosvenor School linocuts did not last long, however. Even before the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. ♠

The Second World War came and the Grosvenor School Closed in 1939. Cooper married Michael Franklin in 1940. They had three children, and she produced no more large-scale paintings, though continuing to work in pastels and chalk. She died in 1992.

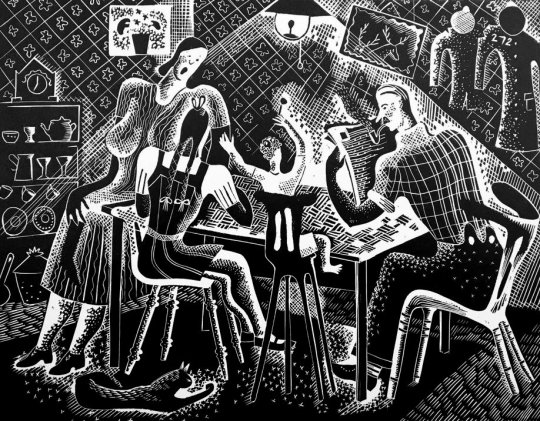

Suzanne Cooper – The Carol Singers

Suzanne Cooper – Street Scene

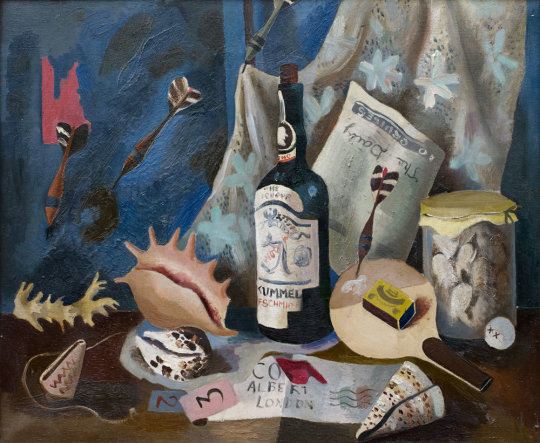

Suzanne Cooper – Still Life

Suzanne Cooper – Renwick Coals

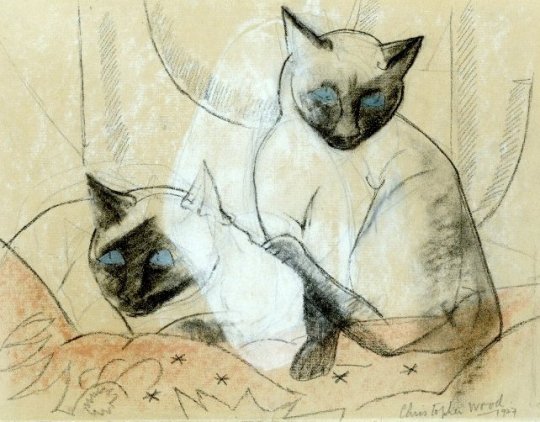

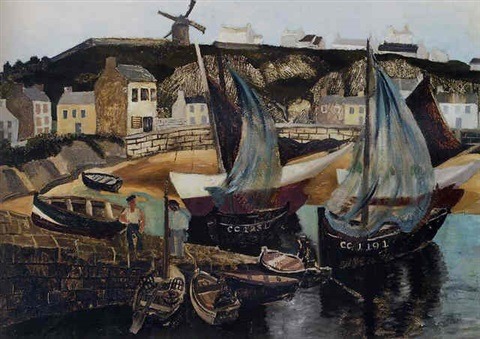

Christopher Wood – Drying nets, Treboul Harbour, 1930

† The Scotsman – Tuesday, 08 February, 1938

‡ Auckland Art Gallery

♠ Lino Cutting and the Grosvenor School of Modern Art – artrepublic

♥ Evelyn Dunbar: the genius in the attic, The Guardian