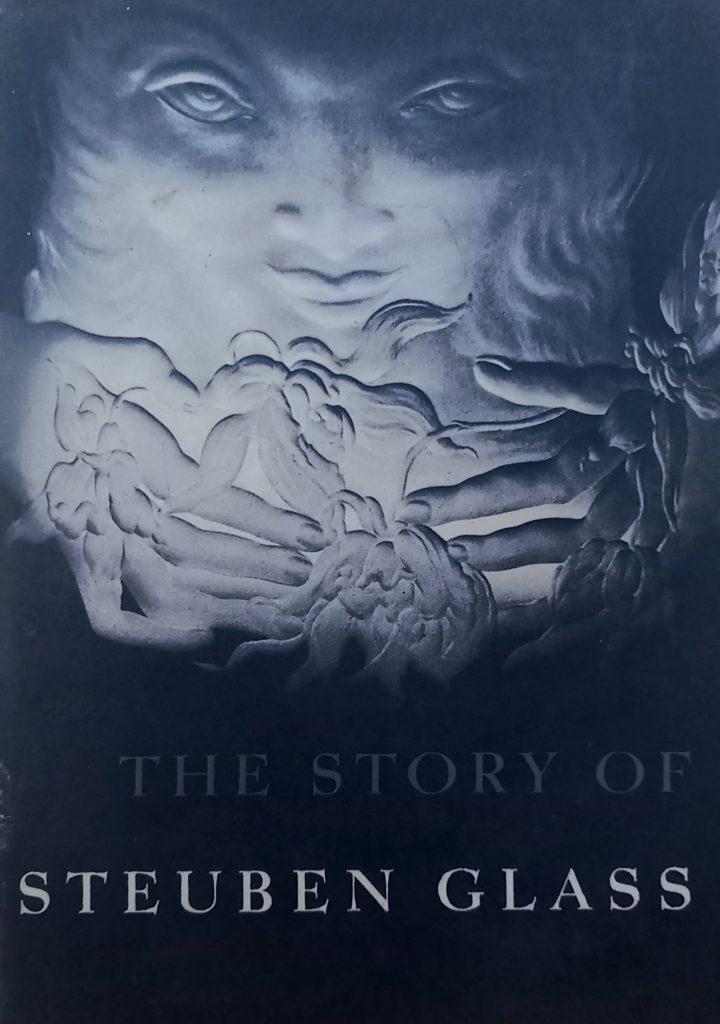

In the 1960’s the Oxford University Press embarked on an expensive project of an illustrated Bible by all the hip artists of the era. It was called The Oxford Illustrated Old Testament: With Drawings by Contemporary Artists. The text used the 1611 King James Version and it came out in five volumes, with a staggered release over two years.

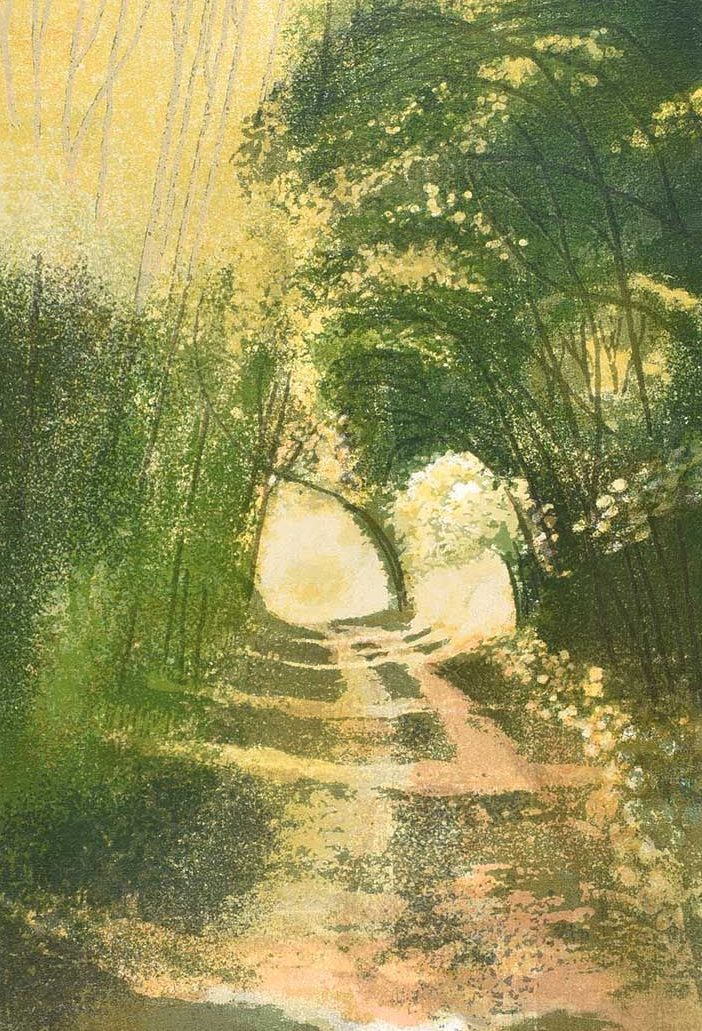

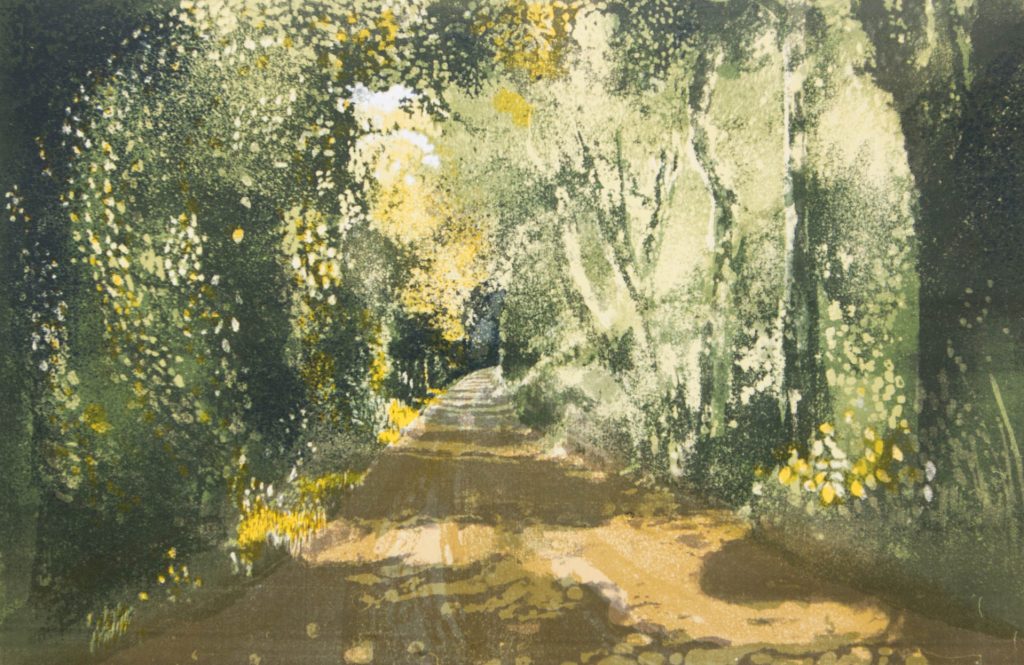

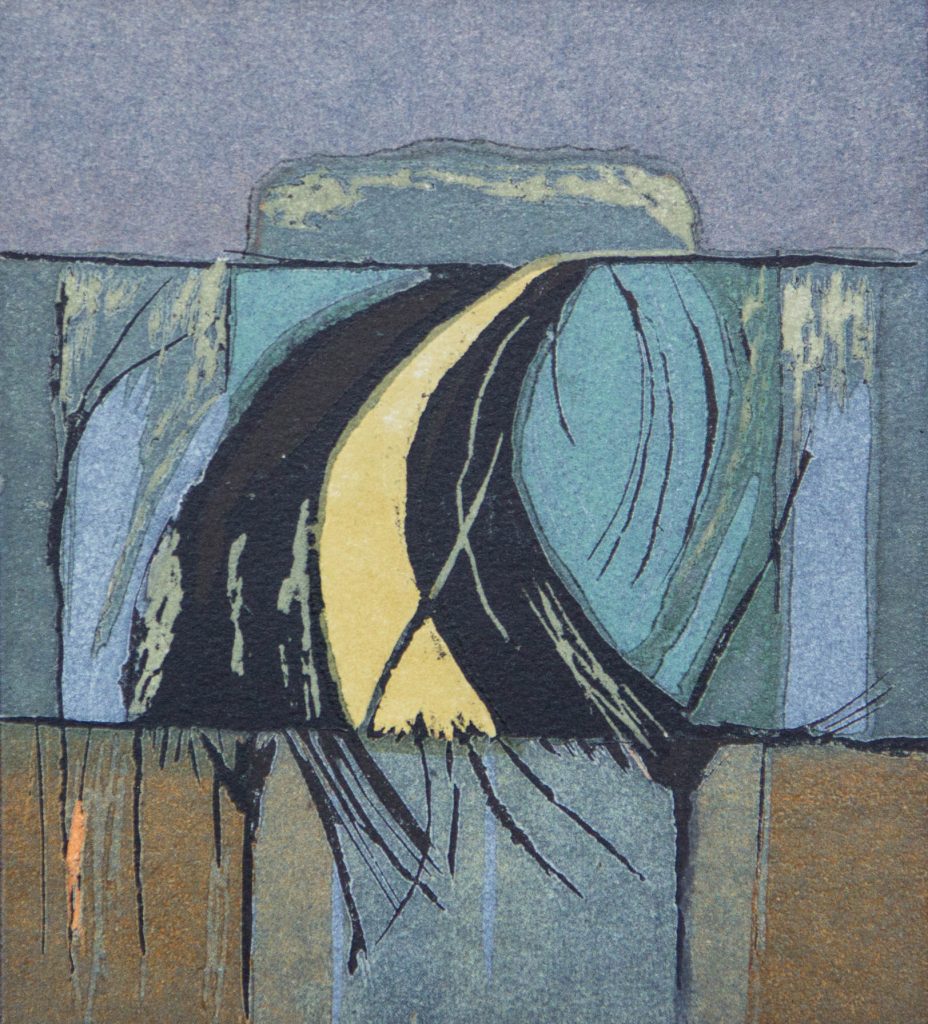

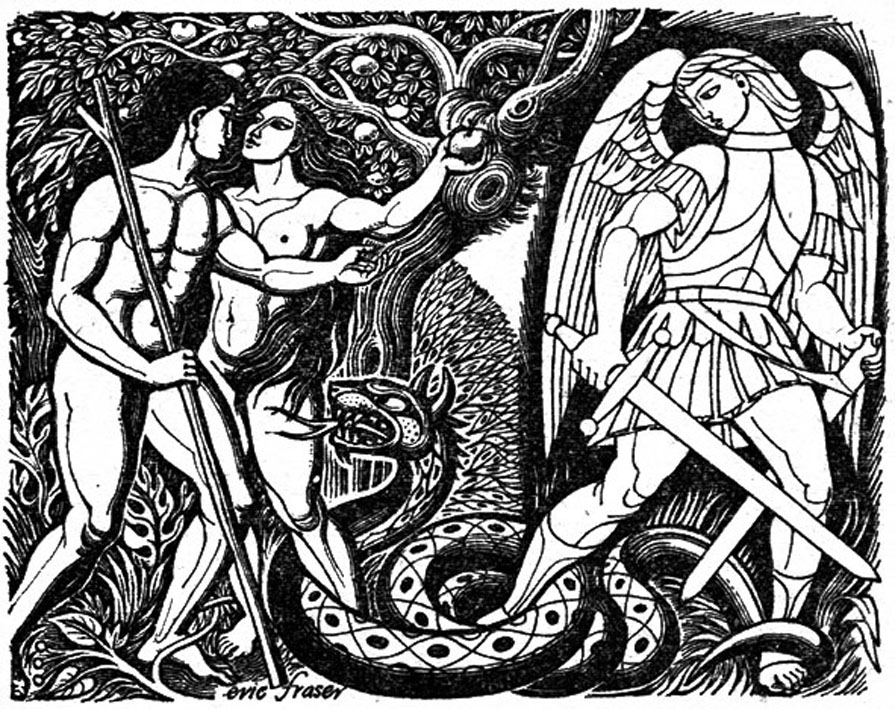

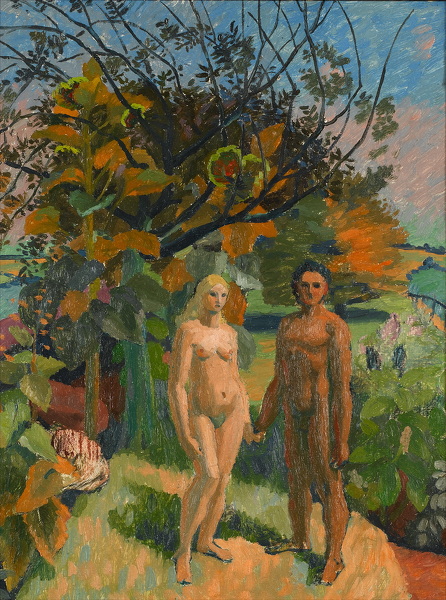

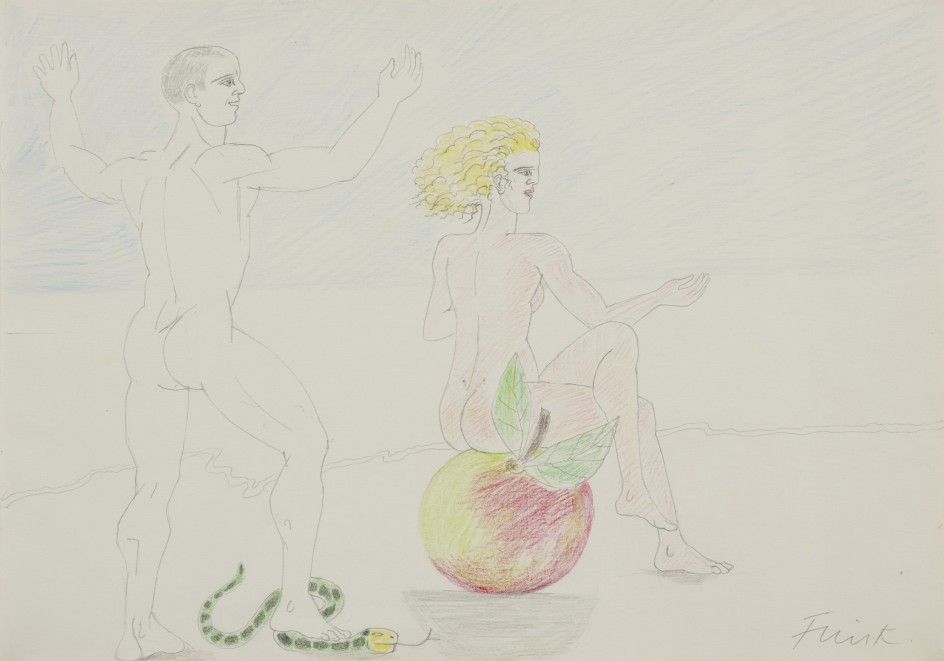

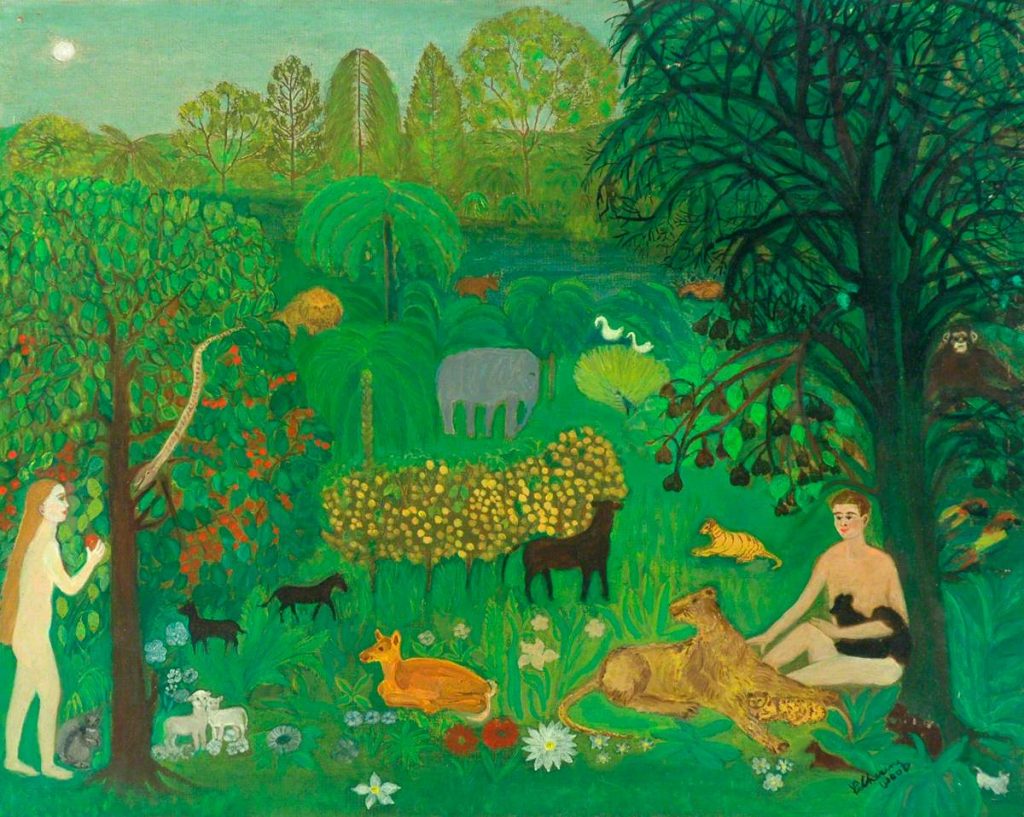

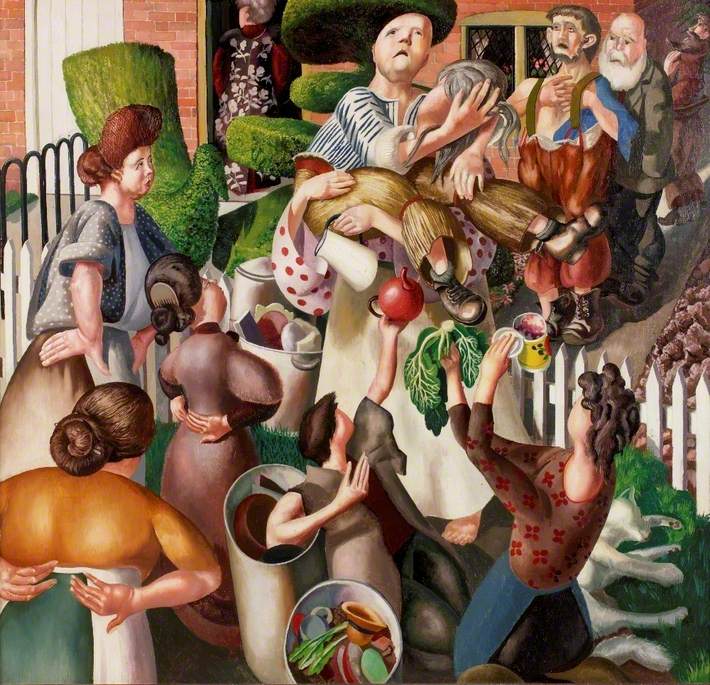

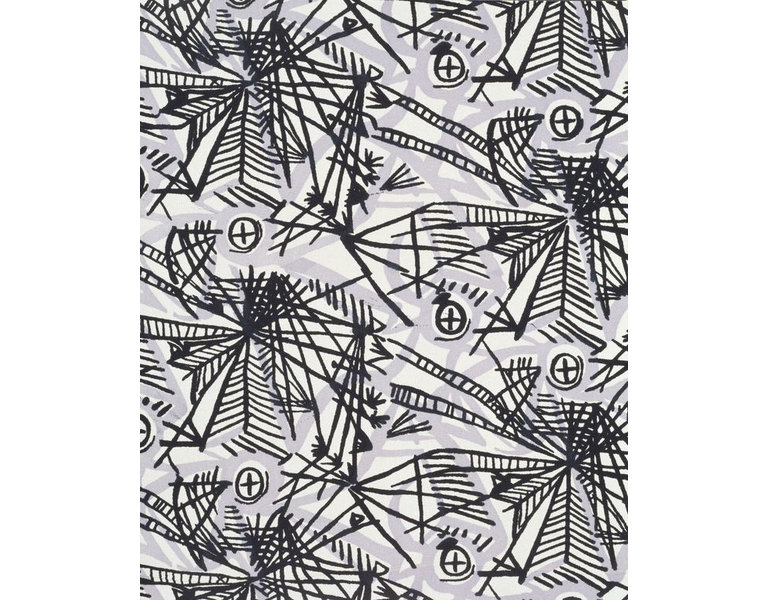

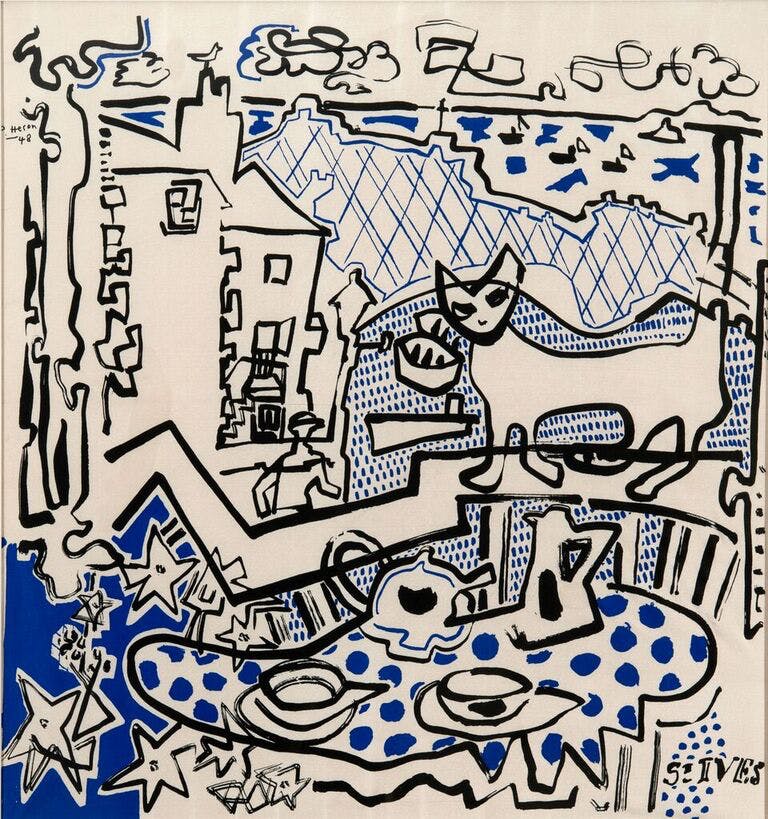

Each volume was a hardback binding and the series had around 700 illustrations. Illustrators include: Edward Bawden, Ceri Richards, Edward Ardizzone, David Hockney; Brian Wildsmith, Peter Blake, Carel Weight, John Bratby, Brian Robb, Francis Hoyland, Cecil Collins and many more.

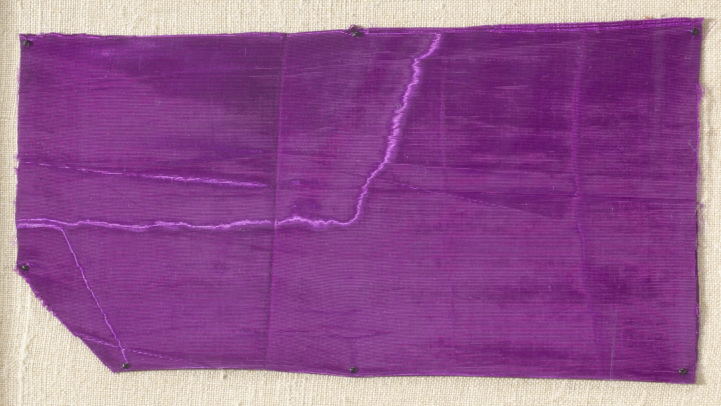

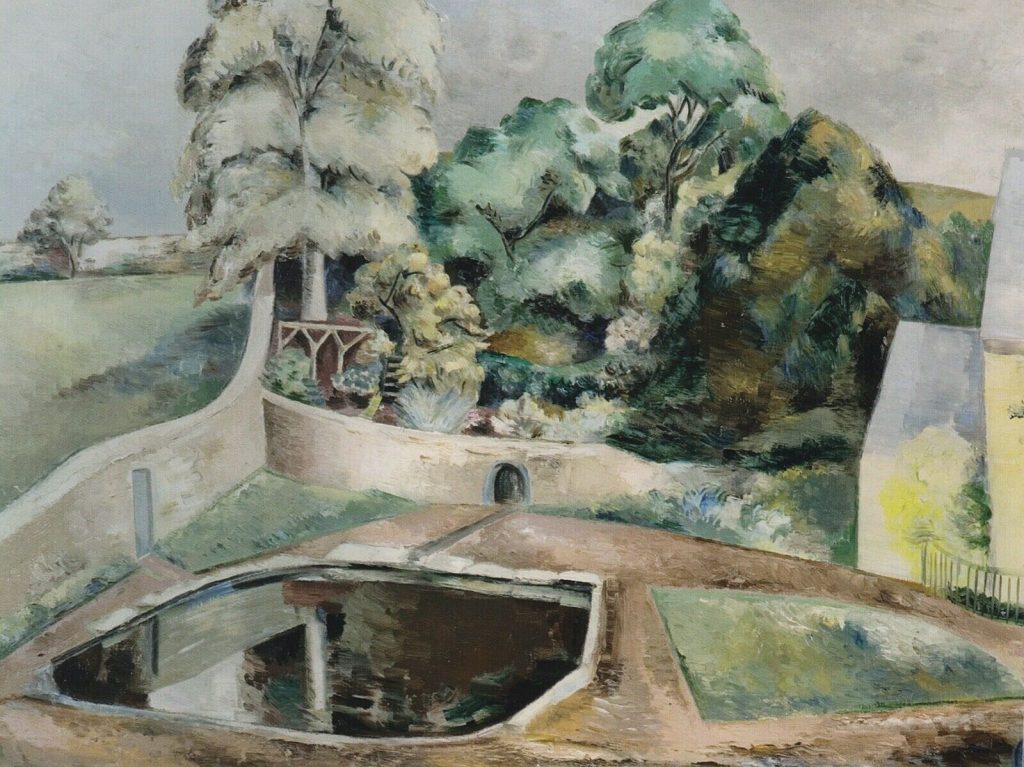

The problem the series had was the expense and the colour illustrations were switched to black-and-white, meaning artists work like Peter Blake and Leonard Rosoman, whose work was vividly colourful turned out to be similar tones of grey.

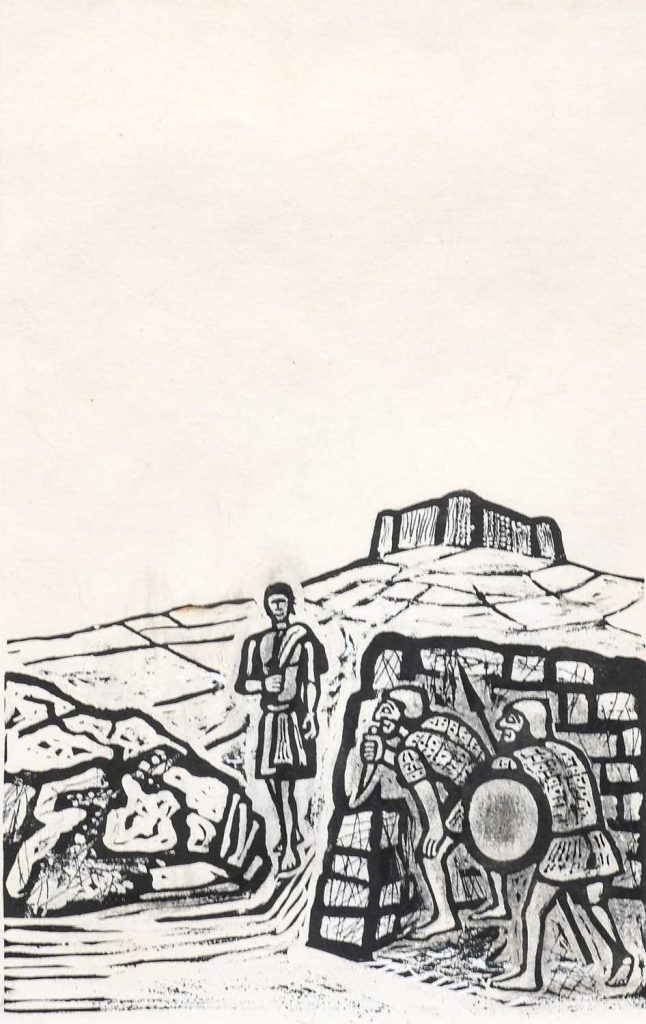

Bawden’s statement on the project:

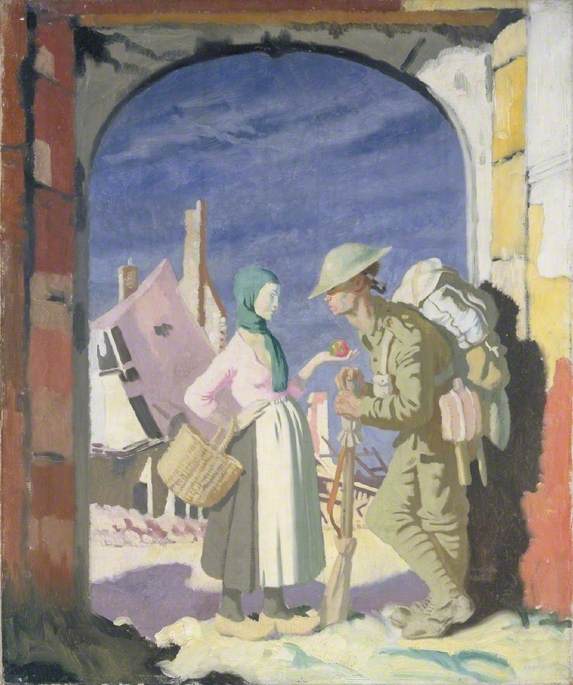

The interest I have felt in making drawings to illustrate passages in the Old Testament, especially for Genesis, might not have been quite the same without having had the experience of serving in the Near East in the Second World War. During a year which I spent in Iraq I was able to draw the Marsh Arabs, later on I made drawings also of the Kurds who live in the mountainous country to the north.

In Kurdistan there was the annual migration of tribesmen and their families from the summer pasture to the winter quarters; flocks grazing and moving slowly forward with the men, followed by the womenfolk on foot or riding on donkeys. It was a scene that might have been much the same when Abraham journeyed from Haran to Canaan.

Nomadic Arabs who live in tents have also an immemorial way of life, and whatever changes may have occurred since Old Testament times, there is today the same impression of life as it was lived in the past.

The account of the lives of the Patriarchs and the description of happenings that took place in those days are extraordinarily convincing as a visual record. There is, however, a feeling of remoteness about this historical past. I have tried to recreate my own impressions of the Near East and its unfamiliar character, the strange desert landscape, arid and hostile, and the tent- dwellers who live in these surroundings, because as an illustrator I would like to identify myself more intimately with the spirit of the Old Testament stories.

The Oxford Old Testament Drawings, RA, 1968.

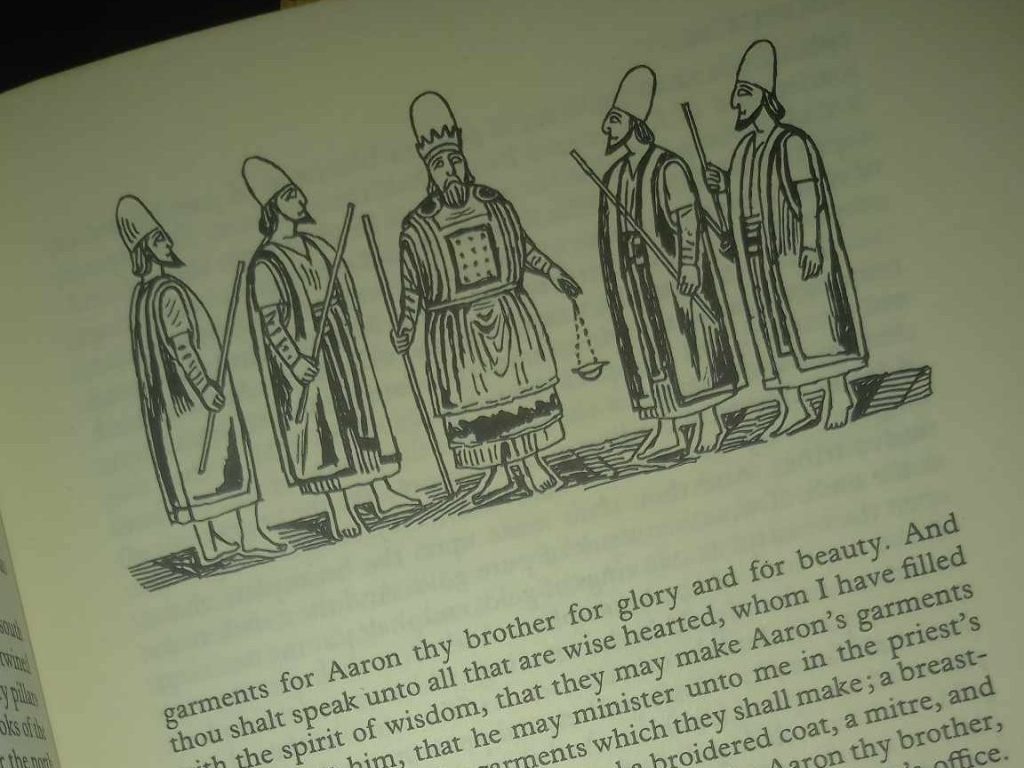

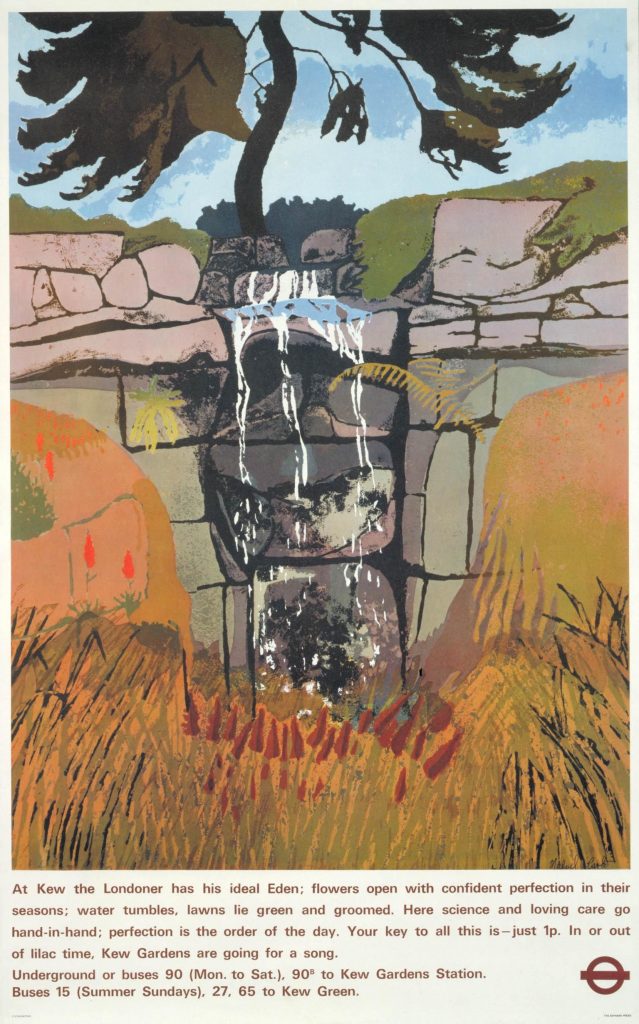

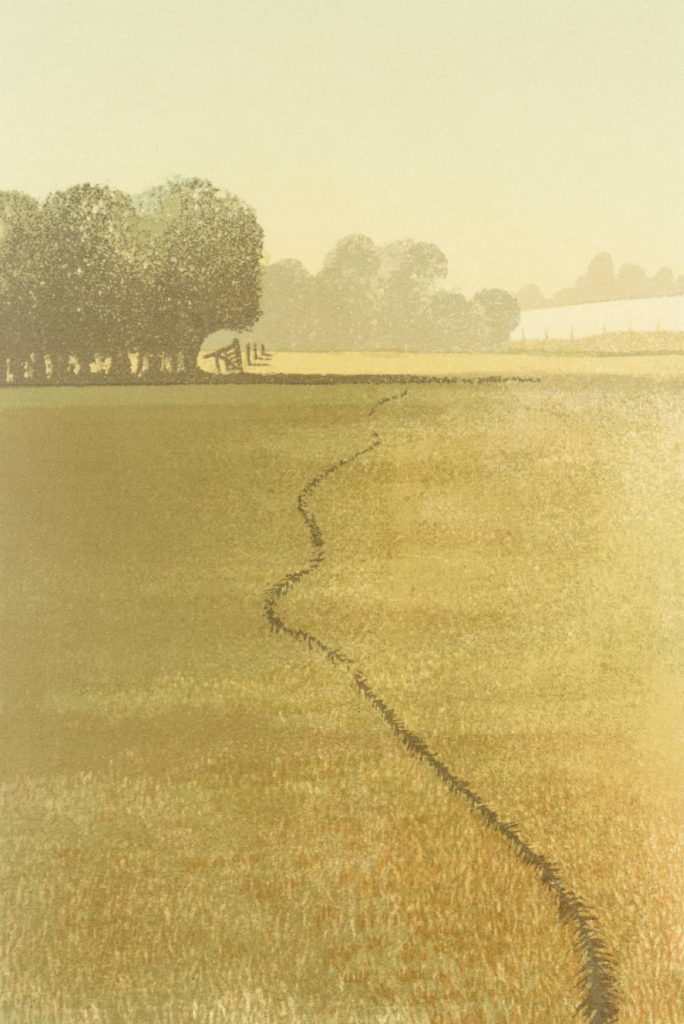

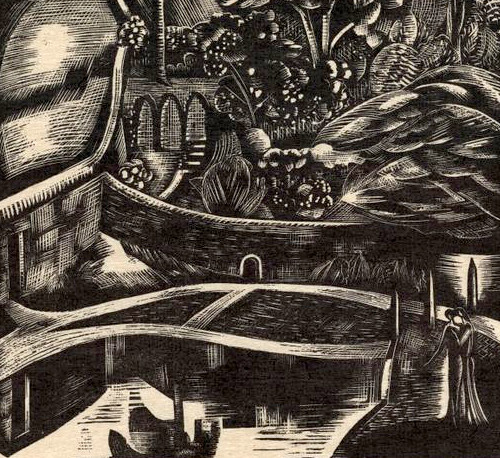

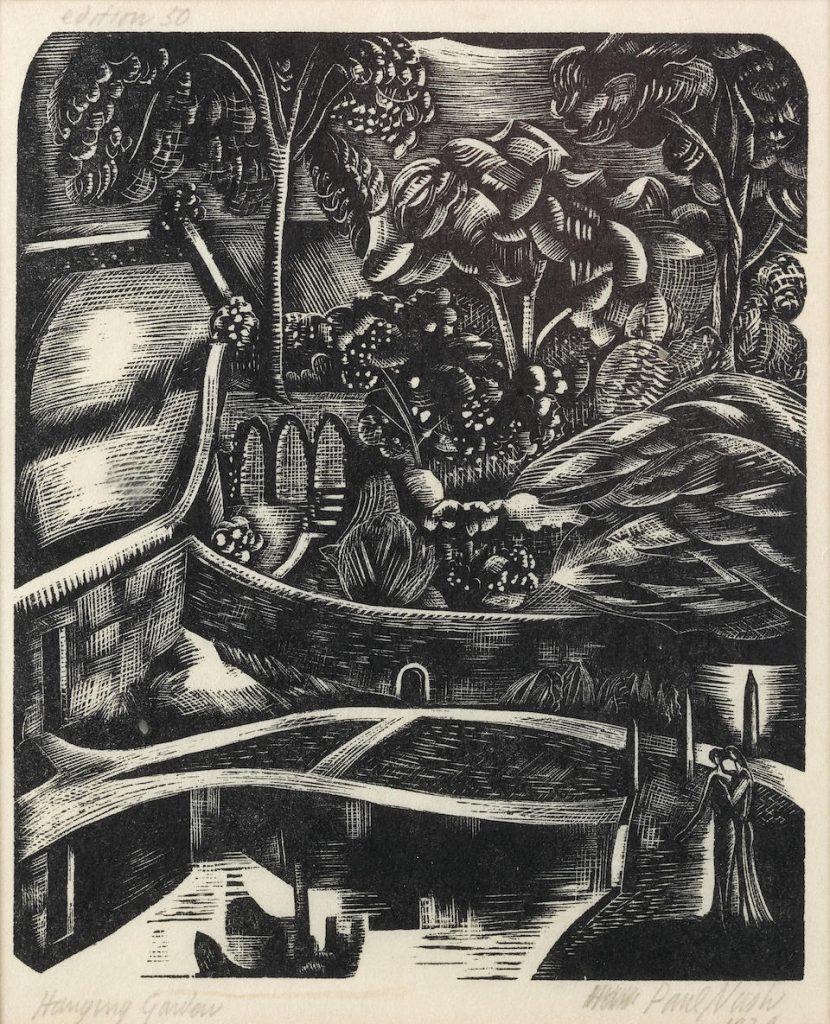

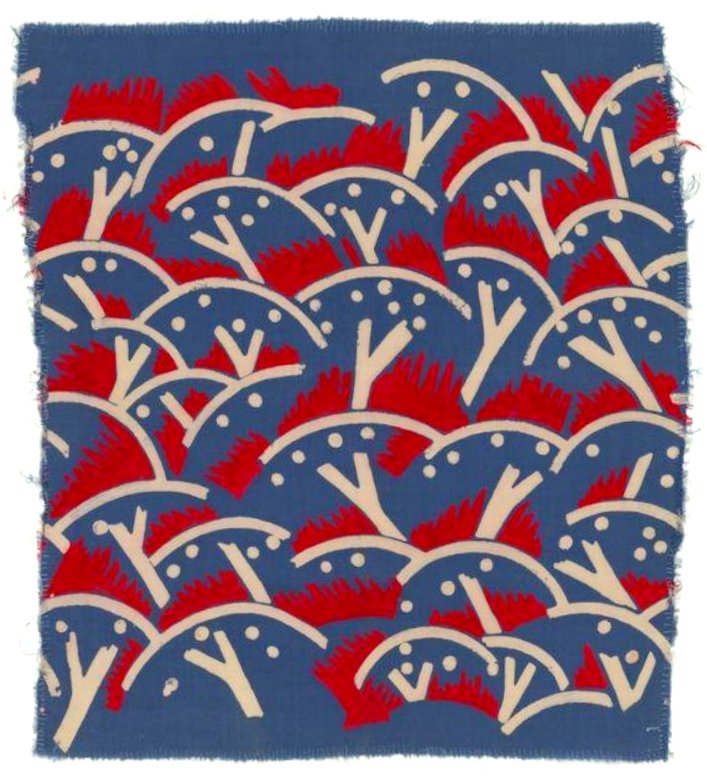

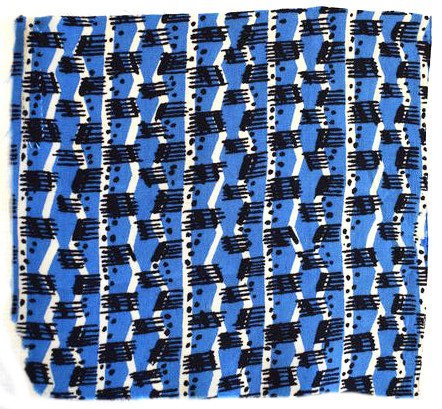

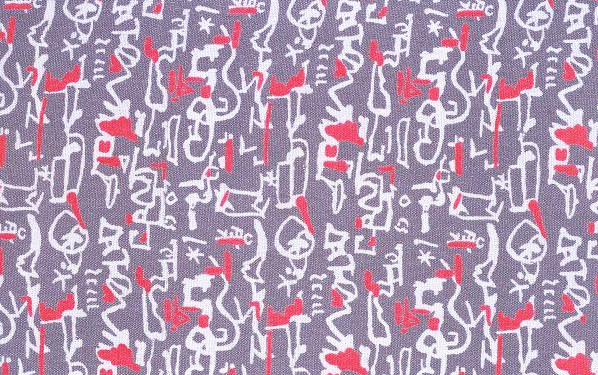

In the first volume Bawden provided line illustrations and then in the later ones they were his drawings with ink painted on as if they were linocuts, a trick he used for many of his dust jacket designs, as seen in the illustration below.

Vol.1: The Pentateuch: Genesis to Deuteronomy (435 pages).

Vol.2: The Historical Books: Joshua to Esther (531 pages).

Vol.3: The Poetical Books: Job to The Song of Solomon (356 pages).

Vol.4: The Prophets: Isaiah to Malachi (532 pages).

Vol.5: The Apocrypha: Esdras to Maccabees (438 pages).

The Oxford Illustrated Old Testament will break away from the old-established tradition of illustrated Bibles by using the work of twenty-two distinguished contemporary British artists. The five volumes will attract the artist and the connoisseur of book illustration, as well as those readers of the Bible who will welcome a strikingly illustrated edition of the Old Testament. All the seven hundred drawings commissioned are on show in this Diploma Gallery exhibition. The majority are for sale. To illustrate Biblical themes is a testing enterprise, making special demands and frequently stirring unsuspected depths of power. To illustrate the whole of the Old Testament in its variety and majesty calls for a group of artists, each with complete freedom to contribute his own vision, his own intuitive or intellectual response. Each artist was invited to undertake a particular book (or portion of a longer book), and each was given complete freedom of interpretation, in any black-and-white medium. The dramatic way in which contrasting imaginative concepts come together in these volumes will, it is hoped, justify the undertaking. The work will be published in five volumes, the first three in the autumn of this year, the remaining two in the spring of 1969. The volumes are divided as follows: 1. The Pentateuch (Genesis to Deuteronomy); 2. The Historical Books (Joshua to Esther); 3. The Poetical Books (Job to The Song of Solomon); 4. The Prophets (Isaiah to Malachi); 5. The Apocrypha. The text used is that of the Authorized Version, chosen as the classic and most widely known English version, a common heritage to which each artist and reader might respond in his own way. Inevitably some of the artists first approached were too heavily committed to accept the invitation, though all were attracted; but an impressive group was finally assembled. Their own comments on their approach to the work will be printed at the end of each volume, and are reproduced in full in the pages of this catalogue.

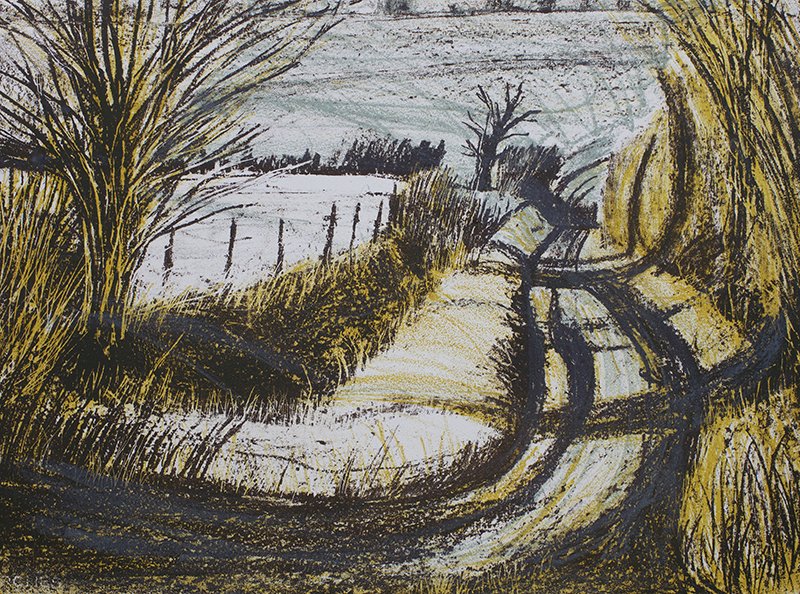

The printing process is offset lithography and the illustrations include work in pen, wash, gouache, chalk and pencil, as well as some etchings. Being drawn for reproduction, some of the originals carry apparent blemishes-erasures and whiting-out marks, for example-that will not appear on the printed page. The illustrating of books is an exacting and, at present, an under-regarded art. This exhibition, and the volumes that are to follow, may help to restore the balance.

The Oxford Old Testament Drawings, RA, 1968.