There are a few good examples of John Piper’s work in Cambridgeshire. They are mostly his stained glass. This time is his work in the Chapel of Robinson College.

The college was founded by David Robinson, a philanthropist who had grown up in the city, working in his father’s cycle shop and making his money from his TV and Radio rental company. In the 1962 he was making £1,500,000 a year and in 1968 he sold it to Granada for eight million.

He found the Robinson Charitable Trust, giving money to Addenbrookes who built the Rosie Maternity Unit, named after his mother, that replaced the Victorian hospital on Mill Road. And two wings, to the old Papworth Hospital and another to Evelyn Hospital.

In the late 1960s he left Cambridge University 18 Million to found a new college, and in 1973 they set to work planning the college. The Architects Gillespie, Kidd and Coia who designed a brutalist style castle. With large red brick building with modernist portcullis designs and towers. The Chapel is a bizarre shape, with a set of medieval style balconies for the congregation as well as a flat platform for rows of chairs.

Like with many of his windows, Piper worked with the glass maker Patrick Reyntiens, who translated his designs into glass and taught piper the practicalities of making windows. They would work together planning, painting and arranging the windows in the design and production.

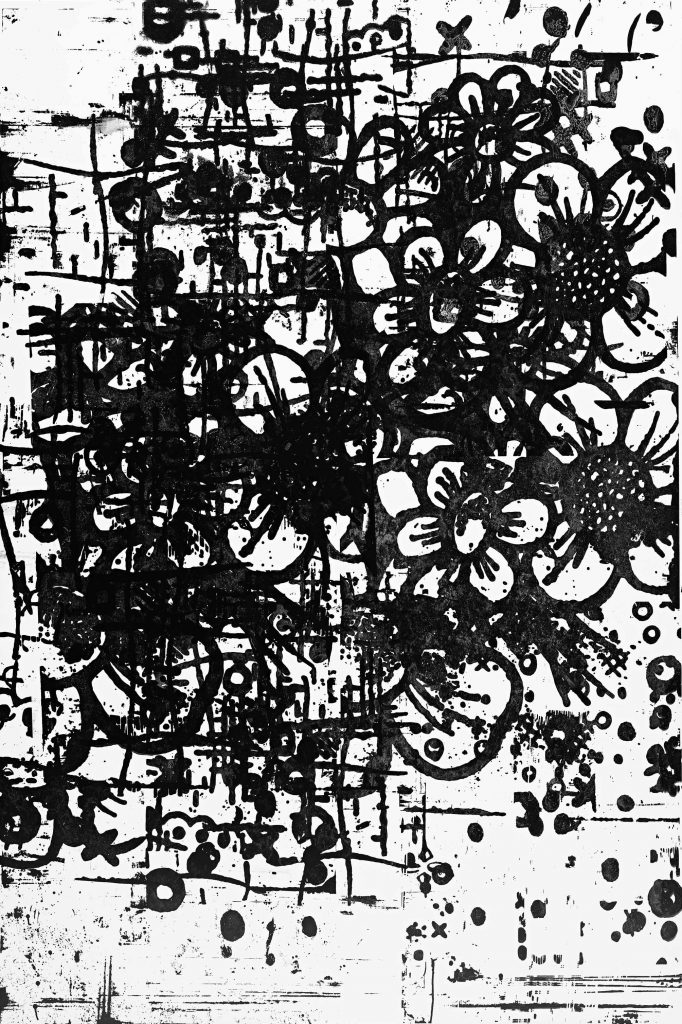

There is a small window in a side chapel and another large window in the main chapel. When questioned about the smaller window Piper explained the design:

There is a small devotional chapel with a window of stained glass of modest size, which shows the Virgin and Child and the Magi bringing gifts. This scene is set above The Sleeping Beasts of Paganism, and in the lowest section are the first and last acts of the Christian story – Adam and Eve with the Serpent to the left, the Last Supper to the right. My designs, with fullsize cartoons, were all interpreted in glass by the Reyntiens studio at Beaconsfield with their usual sensibility and brio. The inspiration for this design was a carved stone tympanum in the Romanesque village church at Neuilly-en-Donjon (Allier) in central France.

John Piper

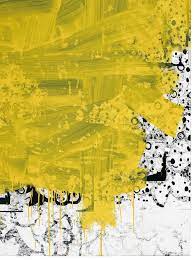

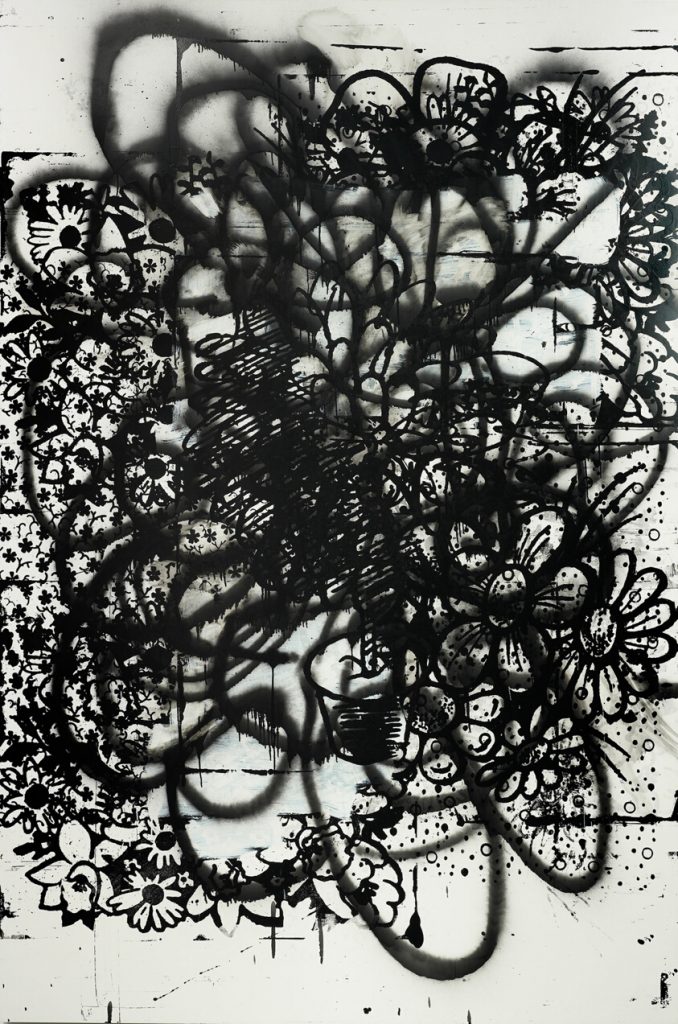

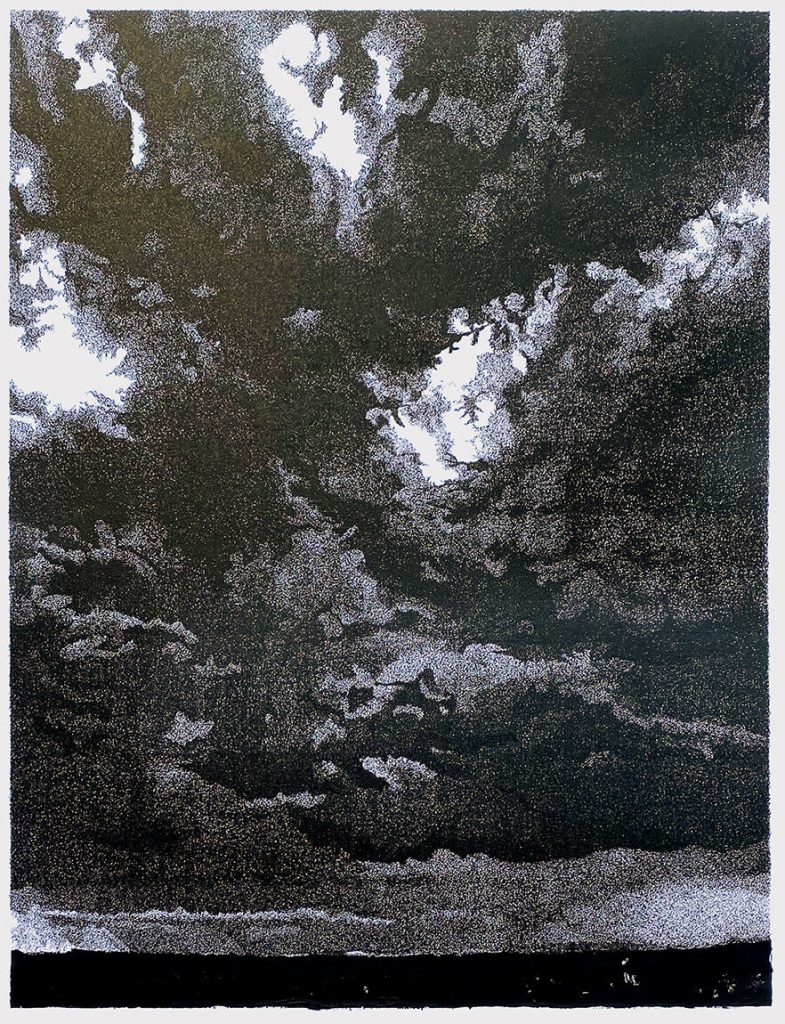

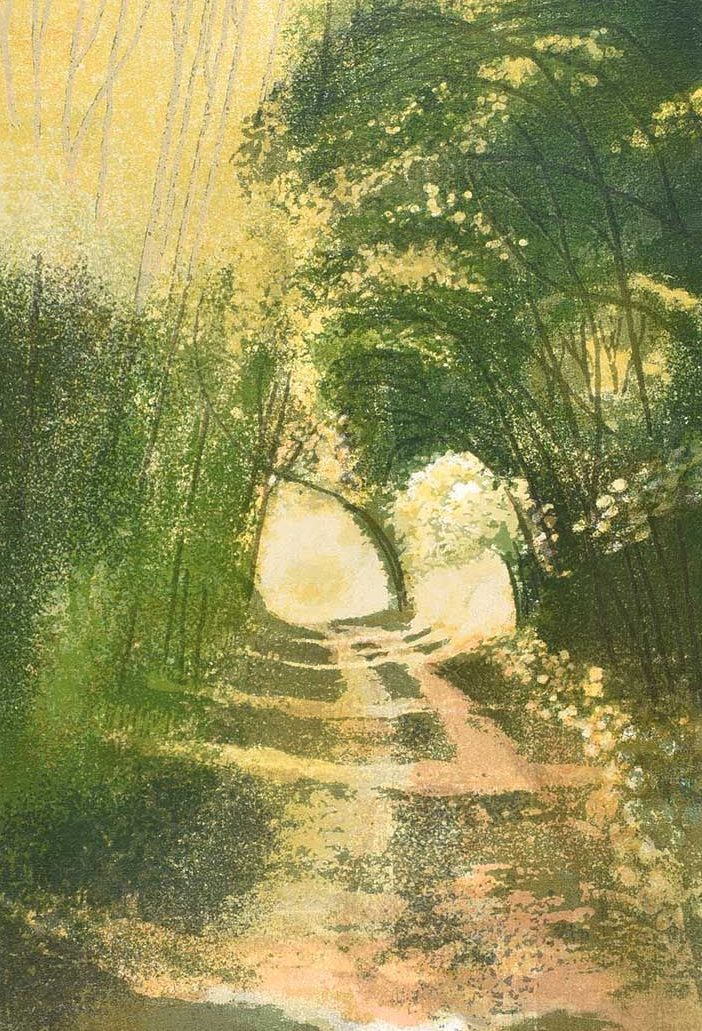

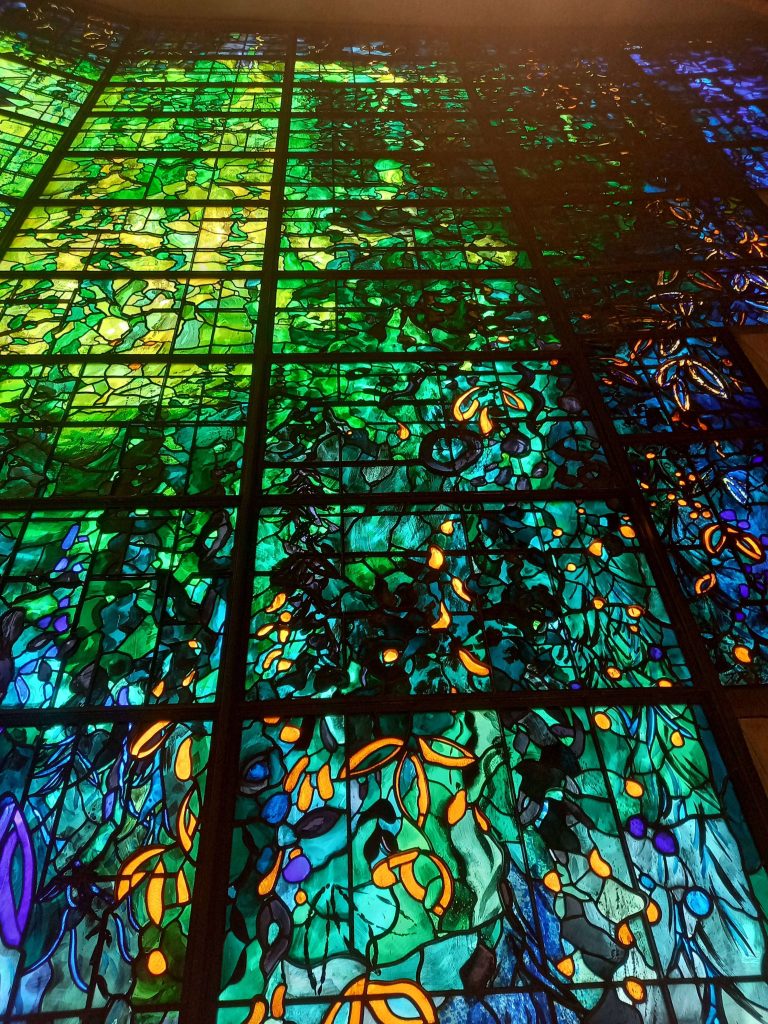

The larger window has the feel of a Monet painting and typical of Piper’s work, has a slow gradient of colour from yellow to green and then blue on the edges.

The subject of the stained glass, which I designed, is a modern ‘Light of the World’, with a great circular light penetrating and dominating all Nature’

John Piper

Piper had become interested in stained glass after being mesmerized by it as a child on a visit to Notre Dame. He wrote about the medieval designs of stained glass and was able to translate his works into windows when he was first asked to design one for Oundle School Chapel in 1953.

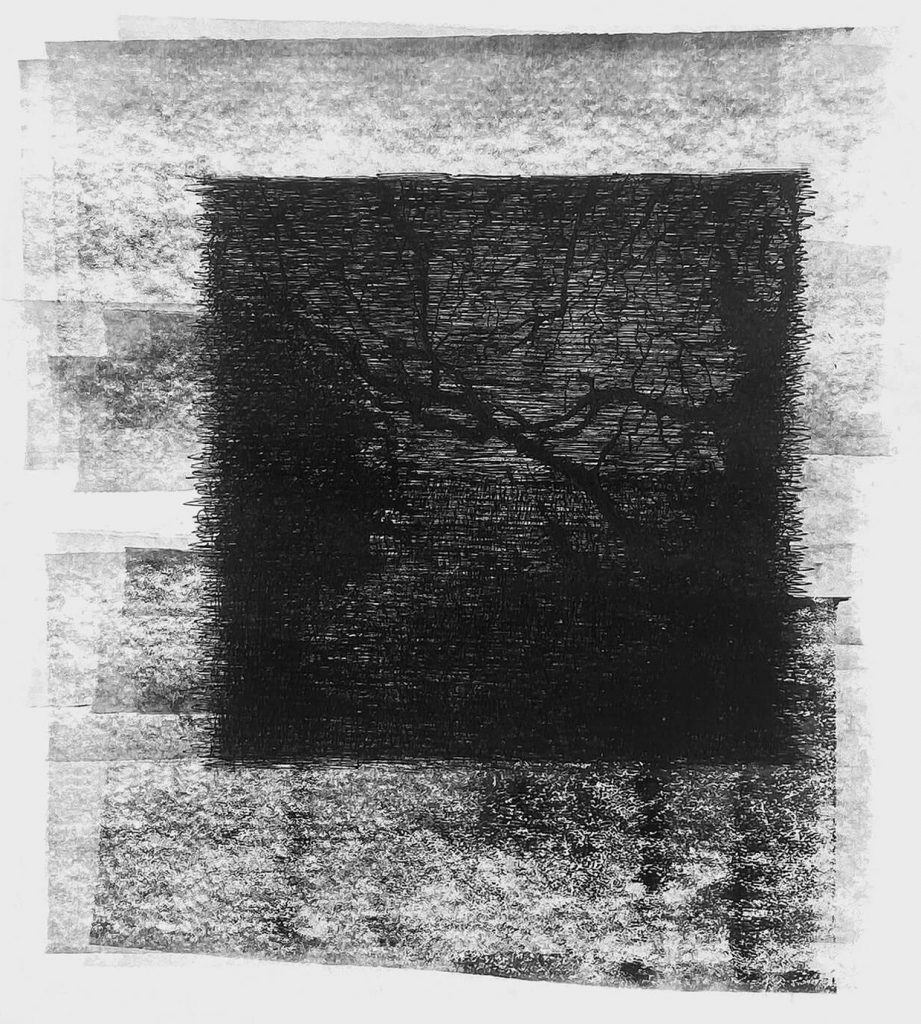

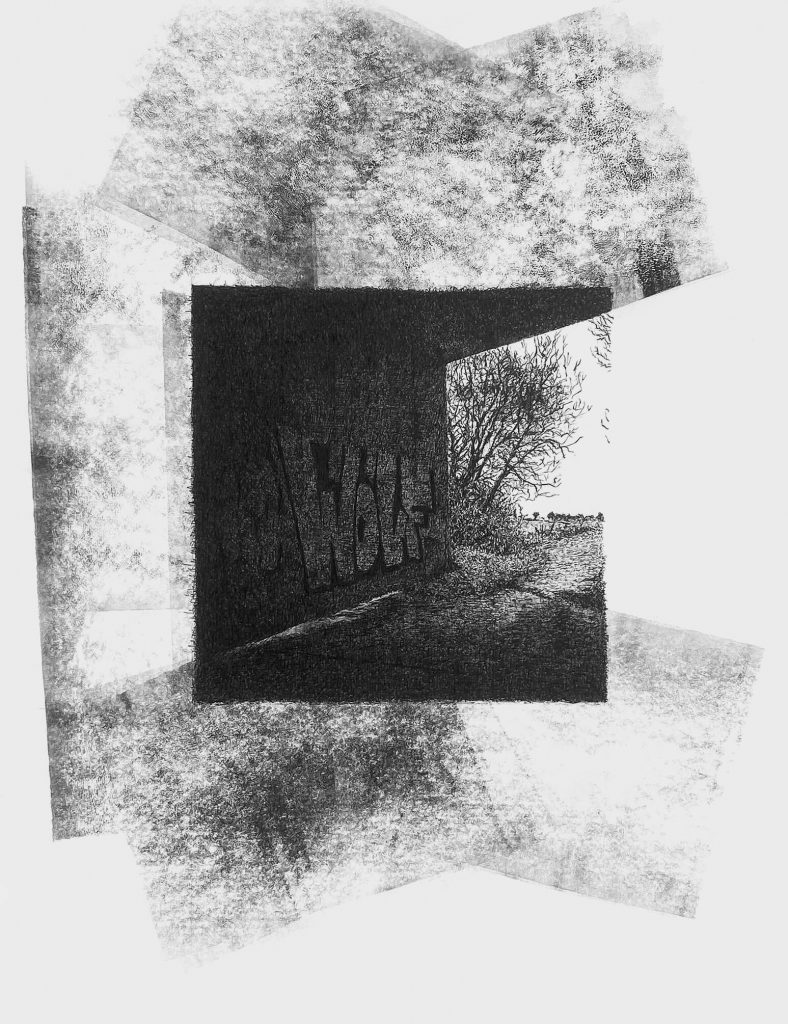

In the photograph below, you can see the chapels original set up when completed. Surprisingly, the lecterns and altar were also designed by John Piper in collaboration with Isi Metzstein. Isi was a German Jewish architect who aged 10 was placed on a Kindertransport and raised in Britain. He trained as an architect for the company that built the college and then worked at the Glasgow School of Art.

Piper formed an excellent working relationship with Isi Metzstein , and became concerned not only with the stained glass, but with all manner of furnishings as well : the wooden cross and candlesticks , the tapestries and altar cloth.

June Osborne – John Piper and Stained Glass