Even before the end of World War II, it was recognised that post-war economic reconstruction, manufacturing and international trade would require the acceptance of Britain as an industrial design and manufacturing source around the world. The pre-war Empire days of British dominance where nearing their end. In 1946, the British Council of Industrial Design held an exhibition called ‘Britain Can Make It.’

The exhibition was held from September to November at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Part of the reason for choosing this venue was that many of the museum’s main exhibits were still in their wartime evacuation storage, outside London. The venue was undamaged by bombing, empty and available, and itself in need of an attraction to restore its pre-war visitors.

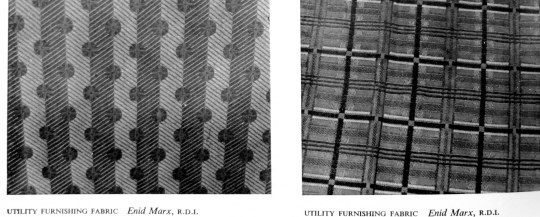

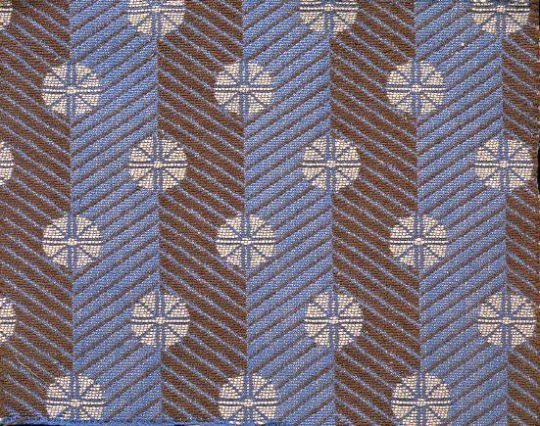

Despite severe cutbacks in production during World War II, the concept of ‘good’ design continued to be of importance and was supported by the Utility Scheme introduced in 1941. Enid Marx was a fabric designer for the scheme, as well as for companies like London Transport.

In the catalogue for the exhibition are essays on design by people like Robin Darwin, Gordon Russell and even George Bernard Shaw. I have copied the piece below from the exhibition catalogue as it is an incredibly rare item and the works and opinions of Enid Marx are also hard to find.

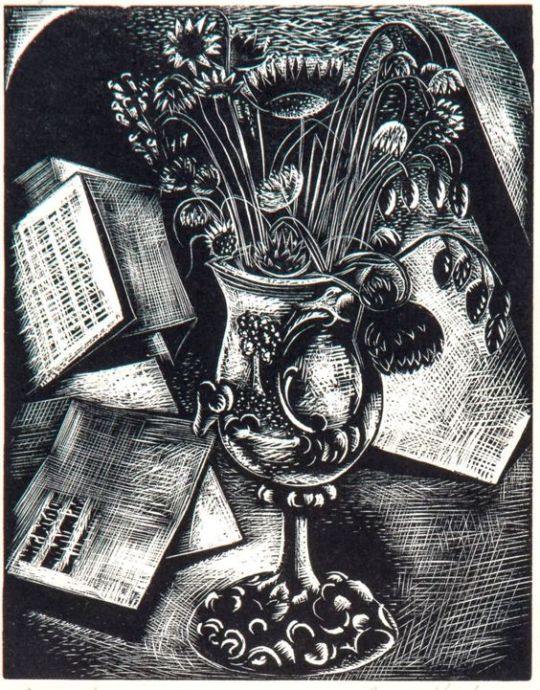

Furnishing Fabrics by Enid Marx

Well over a century has passed since the introduction of machinery revolutionised English textile manufacture and made mass production possible. Since then, technical processes have steadily improved; but it is only quite recently that we have begun to absorb machine-made goods into our aesthetic traditions. Up to now, manufacturers and salesmen have been so concerned with mechanical invention and the chemical problems of synthetic dyes, that all their energies and resources were devoted to these ends. Pattern and design were subordinated to pre-conceived notions of how best to display the elaborate possibilities of the latest mechanical device. Consequently, aesthetic development in English furnishing fabrics stood still for close on a hundred years.

At first sight, this statement may seem a gross exaggeration; but we have only to look at pattern books of early chintzes to realise how little has been done in textile printing in England since, say, 1860, which can compare aesthetically with these designs of the 18th and early 19th centuries. In weaving, too, the brocades and tapestries of this early period have never been surpassed for beauty of design, texture and colour. Imitations and adaptations of these early designs are still best sellers to-day-or, rather, were so before rationing made them unobtainable.

No one would deny that it is easier to achieve high aesthetic standards in hand-woven or printed textiles. All the slight irregularities inevitable in hand-made things enhance their interest and give them vitality. There are not nearly so many steps between the designer and the craftsman and each step is likely to add to, rather than detract from, the beauty of the final result. The converse is true of the mass-produced machine made woven or printed textile. Here each step needs to be carefully thought out at all stages of production if the designers true intentions are to be brought out.

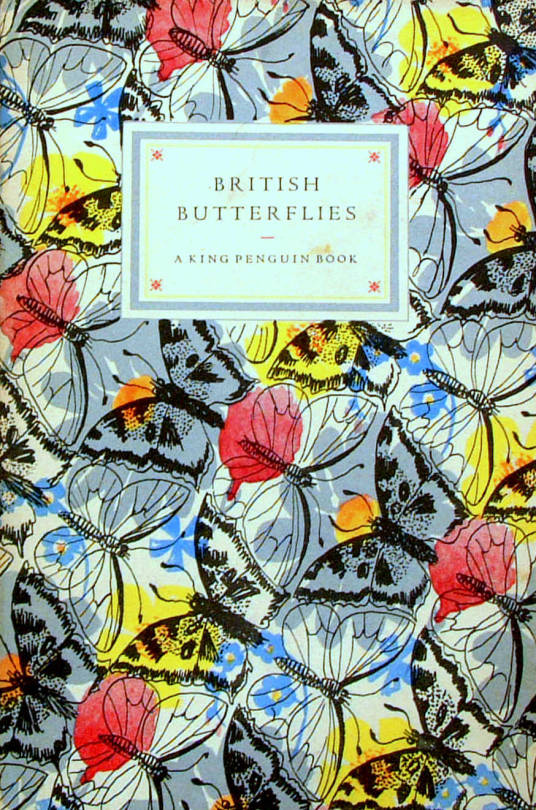

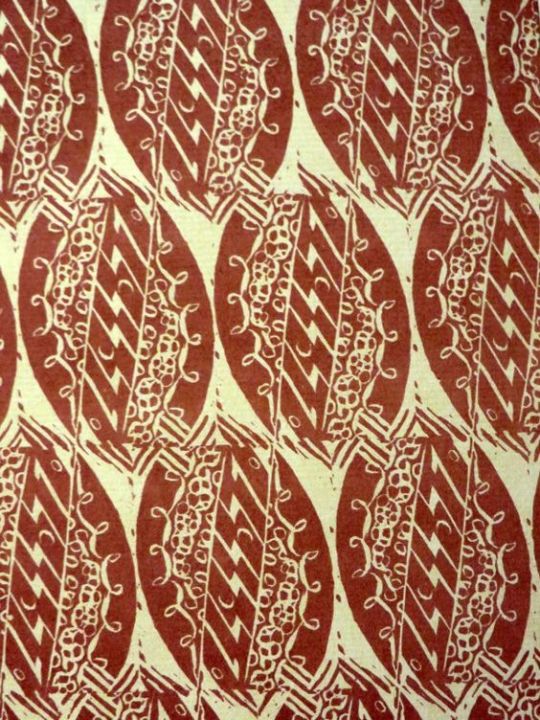

Enid Marx – Spot and Stripe – Morton Sundour Fabrics Limited, for Utility Furnishings.

In England before, and in the early days of the industrial revolution, we had a fine tradition of textile design; the drawing was sensitive, the colours subtle and well used, the textures of the fabrics interesting and of excellent quality. About the time of the Great Exhibition of 1851 we notice a rapid decline in aesthetic standards, and not until the present day has this downward trend begun to reverse itself. Space forbids any attempt to analyse the reasons for this long spell of ugliness, which was by no means confined to England; there are many contributory factors. But one point needs stressing. The decline was not, as is so often stated, due to the use of machinery in itself, but rather to the way in which the machine was used.

William Morris, horrified at the prevailing ugliness, revolted against the machine. How much better if, instead, he had revolted against its misuse and directed his delight in good craftsmanship towards improving machine-made mass production. In looking at his designs for hand block printed textiles we are struck by the way he himself succumbed to the very environment against which he was revolting; they have just that mechanical and wooden quality for which he blamed the machine. It is indeed strange that Morris, with his abounding vitality, should have produced textile designs so lacking in it, in spite of his fine sense of spacing, tone values and the beautiful colours he got through reverting to the old vegetable dyes. Nevertheless that Morris should have had so great an influence on design abroad as well as at home shows how great was the popular demand for an aesthetic revival of the influence of the artist-craftsman.

The vegetable dyes, reintroduced by Morris, have a quality and depth of tone which gives them a richness rarely obtainable with synthetic dyes; though vegetable dyes are incomparably less fast to light. Even today, synthetic dyes tend to be harsh and brittle in colour. Though they can give great brilliance, especially on rayon, this does not make up for their lack of depth. Probably this is because their development has mostly lain in the hands of the chemists who have been fully occupied with the problems of providing colour fastness for the different dying and printing groups, as also for the new yarns and combinations of yarns that are constantly being introduced. We may notice that in France, where standards of fastness are perhaps less high than here, the range of colours used is much more subtle. Our problem is to make our colours as beautiful as they are durable.

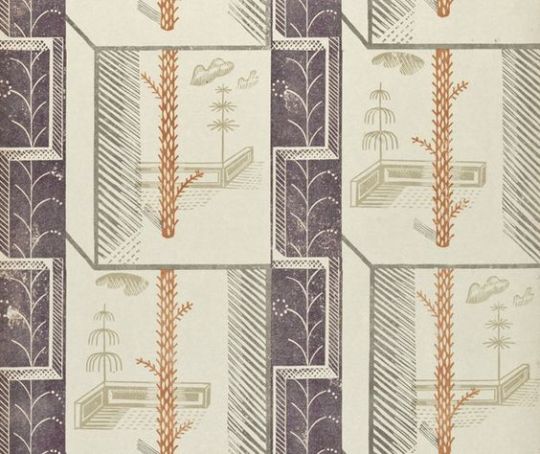

After the first world war, new materials of all kinds came on to the market, as they are about to do again. This had a stimulating effect on textile design. To take one example, the development of laminated woods, with their grained surfaces, for furniture helped to revive interest in the textures of furnishing fabrics. Spinning is the clue to woven stuffs; indeed the spinning jenny was one of the first steps on the road to mass production in the late 18th century. With the new interest in textures in the early nineteen twenties, the more enterprising manufacturers began to study the effects obtained by the hand loom weavers using hand-spun yarns. The new interest in, and experiments with, textures started on the Continent, in Germany, Austria and Sweden especially. Our English manufacturers were slower off the mark, a contributory reason being, no doubt, that we had to make a more radical change in outlook; the English textile industry had been built up during the previous century on the basis of supplying world-wide markets, but now, faced with the growth of native textile industries supported by tariffs in foreign countries, and the competition of cheap labour, we had to think increasingly in terms of quality. The so-called ”folk weaves”, though at first a poor imitation of the hand-woven prototype, and, in the early stages, of poor quality, at least introduced the idea of textural variety for furnishing fabrics. Later there followed cotton and linen tweeds, and other rough surface effects, of a more successful nature.

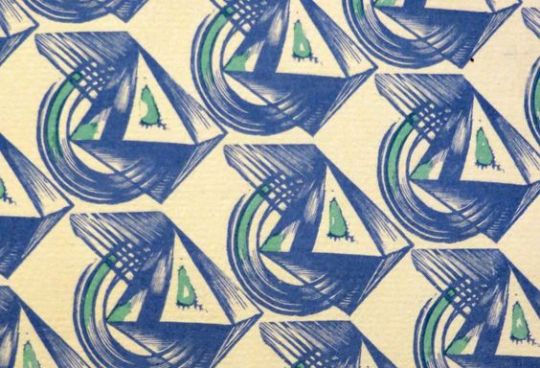

England has, of course, a very long tradition of craftsmanship in weaving. The design of printed textiles responded more slowly to new ideas, than woven ones. The world slump accentuated the problem of printed textiles, namely that the cost of setting up and running an elaborate roller printing machine, with say sixteen colours, requires a very large output for one design, which in turn makes experiments in design costly. But already in the early twenties a number of artists in England had become interested in designing and printing textiles, at first by the hand block method. They achieved considerable success with the decorators and the public. The very simplicity of the means by which they obtained their effects, and the freshness and vitality of their well-drawn designs appealed to the public. Some artists also combined together to design and market screen-printed textiles. Screen printing, being quicker than hand-block printing, was a step towards mass production. It was also adopted by our more enterprising manufacturers as a means of mass production without the heavy initial outlay of roller printing, which therefore made it possible for them to be more venturesome with new designs.

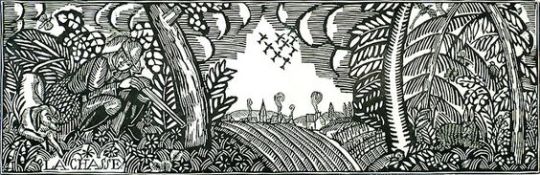

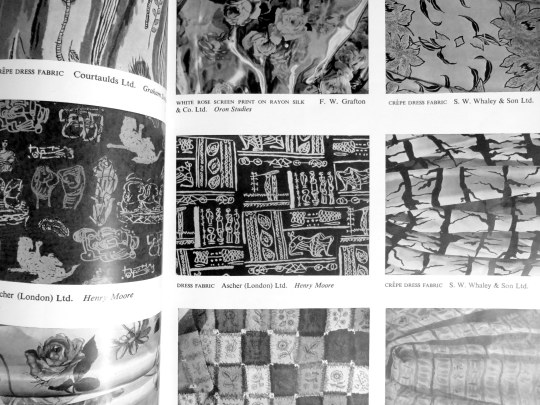

Page from the ‘Britain Can Make It’ exhibition catalogue with designs by Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland.

Hitherto artists had been shy of designing for manufacturers, as they found their designs tended to be changed beyond recognition in the process of manufacture, losing all their individuality. But manufacturers began increasingly to realise the value of artists in bringing in fresh ideas. At last they were prepared to co-operate with the artist in endeavouring to make the final product approximate as closely as possible to the artists original conception, rather than, as hitherto, disregarding the finer points of the design for convenience in production. Such co-operation involves encouraging the artist to work closely with the technical staff. This co-operation has given a much wider range and variety to mass production and appears to be the great hope for the future. Indeed there are many signs that we are standing on the threshold of a great renaissance in English textile design, once the present shortages have been relieved.