This is from an artical in the Countryman in 1941. I thought it was a refreshing perspective on the Women’s land army. It also features an illustration by Mary Fedden.

FACING THE FACTS

It is no use expecting impossibilities of these land girls of whom Mr. Hudson is hoping to see 30,000 on the farms, Their pluck, patriotism and good humour are not in question, but spirited, diligent and sturdy though many of them are, and doath though their employers would be to lose them, the unremitting and efficient work of the regular working women on the farms in Scotland and in some parts of England is nothing fo go by. These women are brought up to the job. They have strength, they know how to take care of their health, they have acquired skill, and they are part of the community in which they live. We believe in women workers and in the Land Army – without it, it will be impossible to get the work done that has to be done – but it will do no harm to print the following letters.

A LAND GIRL IN SUSSEX

Few people realize the extreme arduousness of the agricultural labourer’s life. The billeting question is very difficult too, especially where a land girl is only earning the minimum of 28s a week. I do not know how girls can manage away from their homes on even the highest wage (34s in Sussex) when they have to find board and lodgings, underwear, soap, shoe repairs, etc. In the other women’s services they are ‘all found’ and the rest is pocket money. Also in other services there is a hope of promotion for the hard-working and intelligent girl. You have to be a country fanatic, like me, to stodge on month after month with no prospect of advancement. I think it highly unlikely that many ordinary town girls will become like this. The farm labourer, male and female, is brought up to it.

Another thing – in other services you join and are sure of your living. In the Land Army you may get a job or you may get stood off in bad weather and have to wait for the dole, which means a lot of fiddling about. Again in sickness you have to struggle for yourself, and if you have an accident the compensation money (which is much less than your lost wages) comes about two months after you are up and doing again! That has been my experience. Unless a girl has some savings to tide her over these accidents, etc., I don’t see how she can manage in the Land Army. I expect the various committee members have plenty to do and I don’t know whether they are paid or not, but so far as I can see round here there is no attempt made to visit places of work and see whether the girls are getting a fair deal or not. The girls I have met and questioned are invariably keen on their work and most of them seem hopelessly and foolishly enthusiastic in that they work far longer hours than they should and will. They become fed up and overtired. I’m afraid I sound very much against the farmer, but it is only human nature to work a willing horse too much.

All the girls I have met round here seem to have settled down well and are stones heavier! A few gave up last winter because jobs weren’t forthcoming after training and they couldn’t afford to wait around. Others chucked it after coming to a real dirty farm after training at a posh agricultural college.

Personally I should think the only solution would be a State-subsidized Land Army which would provide security for the girls without worrying the farmers to death. That, to my mind, is the worst drawback of all, for, although no one joins with the idea of earning good money, yet it is a nightmare to be faced with lost wages in bad weather or no care in sickness. Another point is that unless care is taken to stop enthusiastic girls overdoing it we shall have a lot of female invalids later on due to lifting heavy sacks of potatoes, etc.

I have been working for sixteen months now and enjoy the life but have lived at home and make extra money b writing. However, I think that for the average girl the life is extremely hard and boring, as few of them are interested in nature-study or country pursuits, and the occasional rallies and polite pattings on the back from gracious ladies do not make up for their usual amusements, etc. Many girls are quite misled by the recruiting talk and think they will be with lots of other girls and spend their time dashing about on a tractor, and are fed up when they end up hoeing a beet field for about a month and never see a soul.

Of course a lot of farmers are appreciative and the girls get on well; also an intelligent interested girl can do a lot to stir up some of the stick-in-the-muds. At the same time farmers and workers have to learn to pull together a bit more; I know farmers who are still out to do the worker in the eye, and the workers, in return, just slack off. For instance, when daylight-saving makes a loss of working hours in the dark mornings the farmers suggest that the labourers shall forfeit their weekly half-day. It is true that the workers have an actual hour less work every day, but you can’t do anything with that bit of dark morning, while you can do your shopping or gardening on a Saturday afternoon, The worker would rather give up part of the dinner hour every day and put a spurt on if there was some definite amount of work to get through. There is too much domination of hours and rights on all sides. I think the farmers are a bit grinding and many workers are lazy toads. I know I can get through a lot more than many men in a day but not so much as the really old honourable men. You should see how some men gossip and smoke! One last word, the need for going to bed early is absolutely vital.

A LAND GIRL IN WALES

There is a general misconception that the Land Army girls are recruited largely from the urban population. Of sixteen who were training with me at the Henry Ford Institute five or six were farmers’ daughters and half the others were country bred. The very heavy mortality of the early days of the Land Army was, it is true, largely among the town-bred ex-shop assistant, typist, factory-worker type, who had not in the least realized what the job meant and were not physically up to it and in some cases too squeamish to face cleaning stables or burying dead lambs. It was the fault of the recruiters who were so anxious to show spectacular numbers that they did not warn recruits that they were committing themselves to long hours, dirt, outdoor work in wet weather and, very frequently, to a seven-day week. I think present recruitment is much better and the percentage of failure will be less.

Hours are a problem. The original stipulation was a 48-hour week, but it has proved quite impossible for farmers to work the girls different hours from the men, and men’s hours vary from 48 to 54 without overtime or Sunday work. In hay harvest a 14-hour day is quite normal (7 a.m. till 9 p.m.), and 12 or 13 hours in corn harvest. It isn’t possible to let the girls off earlier because a full team is always necessary to keep the balance even between field and stack.

Loneliness is a real trouble where girls are working singly on small farms, What they want is not mass entertainment but individual invitations to Sunday lunch, tennis, or even family evenings. Most of the L.A. seem to come from homes more educated than those of the cottagers (or even the farmers) with whom they are working and they miss the more intelligent (or intellectual) conversation of their homes and previous friends, The loan of books would also be much valued by many.

A MIDLAND FARMER’S WIFE

Several farmers round here have had very good girls for some time. One farmer has three from Birmingham who are first class, he says. It really depends on the farmer as much as on the girls. The most urgent thing is milking and care of stock. In these there is no doubt that a great many women excel.

TWO SOUTH COUNTRY FARMERS

Many of the girls know as little, of course, of the realities of rural life and farm life as most townees. And much of the work they gallantly essay is physically beyond them. They do it slowly and imperfectly. And when the first excitement has worn off, they are sometimes dispirited by their inefficiency, When they are thrown back on themselves, their opportunities of marriage having been diminished by the War, they are heart-sore. Land work, even though to sustain the Home Front, can seldom seem as exhilarating and satisfying as the life in the Services that their men friends are leading. Also, unlike the soldiers, sailors and airmen, the girls are not ordinarily working with a large company of comrades. It must often happen that they are almost alone, with very little social life, recreation or entertainment. If they are not in some measure self-sufficing as readers or students, and have no special devotion to the countryside, the life must seem to many of them dull and toilsome.

It is not backache only that is the matter. Many girls at work in towns are underfed. Even if in the country they have not to put up with chancy fare but have satisfying meals, there are those among them with a stupid fear of putting more flesh on their bones than the women of the films or cheap fashion papers seem to manage with. Again, these newcomers to the country seldom realize that early rising and hard work day by day on the land means early to bed. What with one thing and another, many a well-meaning land girl has sometimes in her early days been not far from hysterics. She feels lonely, incompetent and fatigued. In the result, the employer is as dissatisfied with her as she is dissatisfied with herself. Often a sensible farmer or farmer’s wife or some understanding soul in the village gets matters on a better footing before dismissal comes about; but it is not seldom for employer and employed to part company without regret. Nothing can be done with a silly girl, and it cannot be expected that there will not be some very ordinary young persons among the recruits to the Land Army as to the Army itself, but by taking thought, much more can be done than is perhaps being done with some of the apparent failures. Because of the national extremity, it is vital that the best wits

of the countryside shall be brought to bear on a human problem. Cannot some of the girls be given sounder notions of hygiene?

In August 1918 a survey was taken of 12,637 Land Army members (writes Dame Meriel Talbot in the Times’). The returns included 5,734 milkers, 293 tractor-drivers, 3,971 field workers, 635 carters, 260 ploughmen, 84 thatchers, 21 shepherds. Can we doubt that with the extension of physical fitness, the development of motor-driving and every kind of outdoor sport, members of the present Women’s Land Army are capable of surpassing the pioneers?

A FARMER IN HAMPSHIRE

On my farm I have five land girls, and on the whole we are pleased with them, one with cows, one with poultry and three on the arable. We have had to get rid of one,a good girl, from the dairy, because she wouldn’t go to bed at a reasonable time, and couldn’t get up early. There is a camp too near the farm! There are bound to be misfits and faults and shortcomings on both sides, and I doubt if you can do anything about it, except leave it for time to solve. You can’t put ‘gumption’ where there isn’t any. You can’t make an unhandy man or woman handy, and literacy and good manners don’t mix with their opposites.

I think we on the land have to do the best we can, and, in this machine-age, if we are left a certain minimum of skilled key men we can rub along with second-rate labour, male or female. And I’d sooner have girls than second-rate men, if they will try.

A SCOTTISH LAND GIRL

Women farm-workers often have to pit their strength against men. Everything is made men’s size – the heavy tools, the thickness of sole necessary to keep out the ‘glaur’, the size of the enormous straw bunches and hay-bales. Now if a woman is given work within her strength she can go on all day, but five minutes of lifting heavy bales, with the best will in the world, will tire her out for an afternoon (between four and five hours) – bales that a boy could lift (there must be some anatomical difference). If she is strong-minded she can often save herself; for instance, in fanning corn, she may be told to fill the fanner by lifting the grain up in a heavy basket the height of her brow – if she uses a pail instead she can equally well keep the fanner going, but ‘it is not done’ the others will say (this happened to me only this week). But what does the land girl get out of her new life besides ‘rude health’ and a good deal of fatigue? It must be remembered that people on farms are still merry – such merriment, whistling and jokes as in time of War you find only among soldiers, sailors and others engaged in active service. The older labourers are still interested in their craft for its own sake, apart from production of food. This gives a steadying background.

The definiteness and richness of the country character with his telegrammatic (or poetical) way of putting everything appeals to every girl. He makes ‘story’ for her. She is delighted with a clear outlook that you now so rarely find in towns (compare the weather talk of the stable before yoking time in the morning with the glib repetitions of shop girls). The newcomers are allowed to melt into the communal life in a most kindly and welcoming way (I find it hard to get an evening to myself) – there are dances in local granaries and all the excitements of human happenings: births, deaths, removals, marriages and miscarriages.

I am working in the poultry now. A Japanese ‘sexer’ comes every week the day after we have hatched to divide the boys from the girls. The girls we sell as day-old pullets. Imagine my horror when I was asked to take and drown all the boys. I felt like Herod. Did it just once, but have said never again.

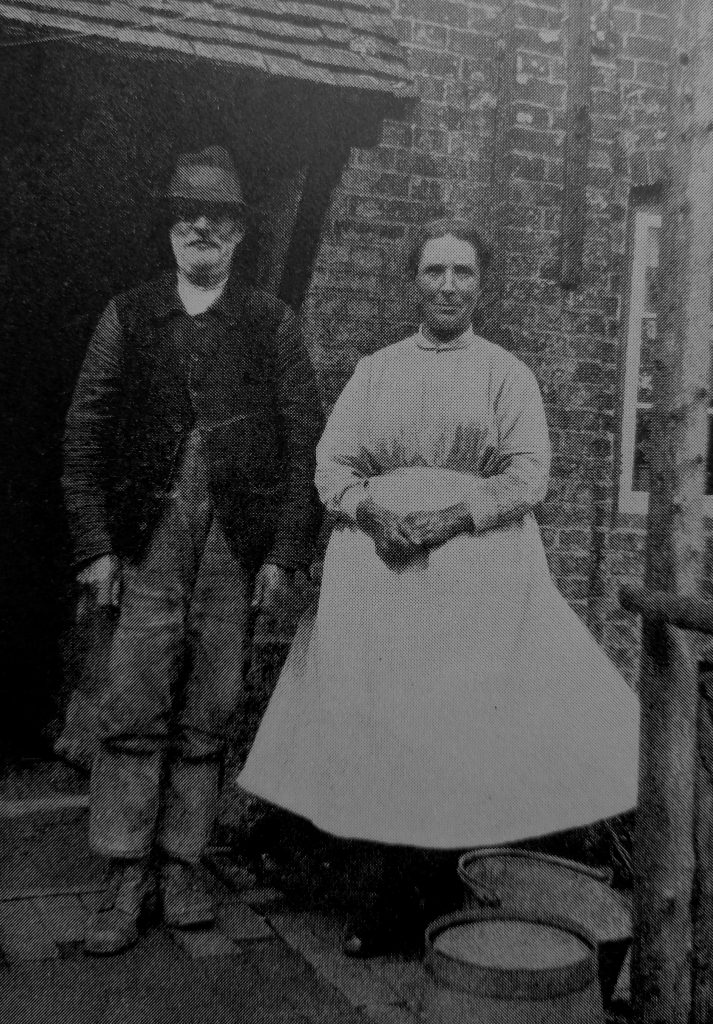

ABOUT THE SCOTTISH BONDAGERS

How many English people know the word? The dictionary definition is, ‘A cottar bound to render certain services to a farmer’. To-day a cottar is a farm servant who occupies a cottage on the farm as part of his wages. The word recalls the time when both men and women were serfs. It has now come to mean women workers only. The picturesque costume, with differences in the colour of the skirt, and in some places the wearing of a sunbonnet instead of a wide-brimmed straw hat, as described by ‘Scottish Home and Country’, from which the illustration is borrowed, is one of the few female national costumes surviving in Great Britain. The skirt is of stout orange and black drugget, requiring three yards of material, and has thirty-eight pleats. The binding is done with a bright-coloured braid. The gay apron is worn of course after work is done. The garibaldi is of bright print, buttoned down the front. Over the hair a kerchief – a square of print folded in a triangle – is worn, with the two ends tied under the chin, giving a nun-like effect. What is not shown in the photograph is a small brightly-coloured or tartan-fringed shawl which is pinned closely to the neck, the two ends thrown over the shoulders to fall down the back. In wet weather the bondagers are ‘breekit’. They pin their voluminous skirts together at the knees and wear a coarse apron or brat. Straw ropes are wound round the legs to protect them from the wet and mud.