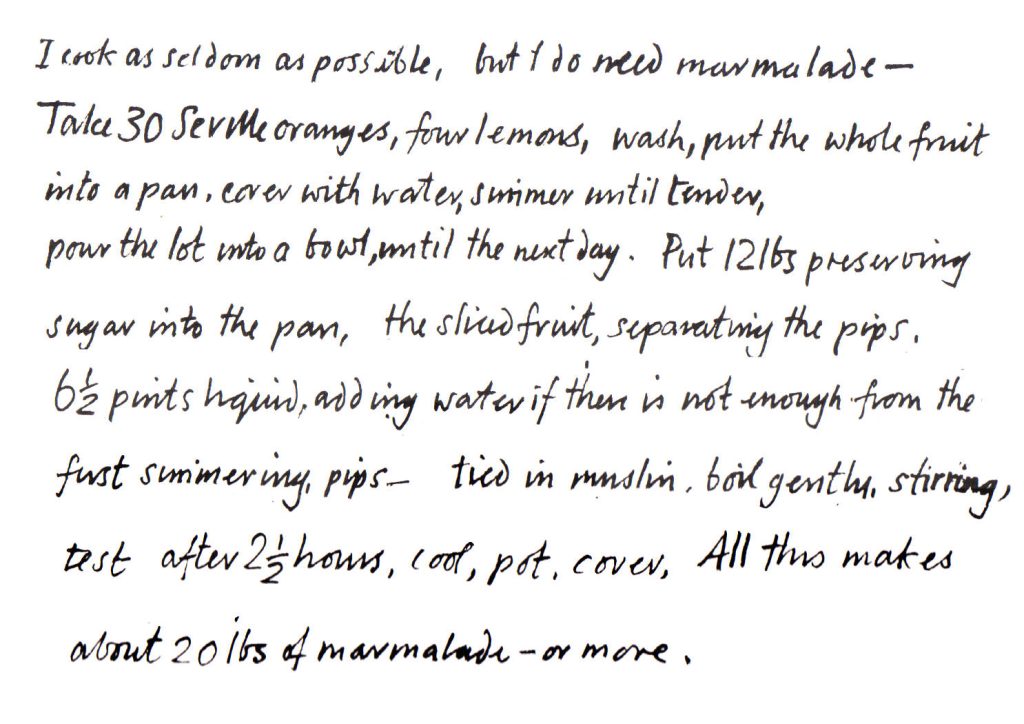

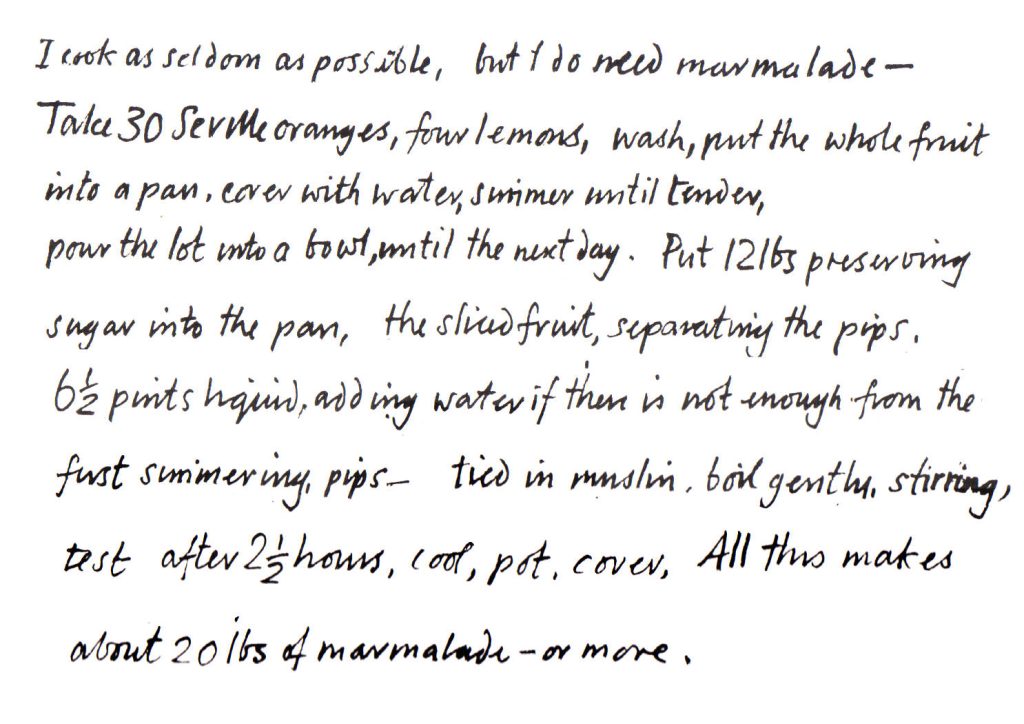

There might well be a little booklet to be made on the recipes of the Great Bardfield artists. Aldridge, Bawden and Rothenstein all wrote some down. But for now here is Sheila Robinson’s recipe for Marmalade in her own handwriting.

There might well be a little booklet to be made on the recipes of the Great Bardfield artists. Aldridge, Bawden and Rothenstein all wrote some down. But for now here is Sheila Robinson’s recipe for Marmalade in her own handwriting.

This is an article I found in a book about the open house exhibitions of Great Bardfield, posted in the Daily Mail. 7th July, 1955. It rather overlooks the work of the women, but I enjoyed the tail of Bawden getting a bucket of water thrown over him.

‘Come Into My Parlour,’ say the Artists of this Village Academy.

The population of Great Bardfield, an Essex village about 40 miles from London, is 900. Its attractions include four pubs and nine artists.

This works out at an average of 2.25 artists per pub, a dispersion sufficient to enable them to co-exist amicably in so far as artists ever can it being well known that an artists’ colony is one of the trickiest of all colonial enterprises.

Great Bardfield’s nine sternly insist that they are not a Group or a School, but nine people who happen to live in the same village. Once in a while, however, they become collective, if not a group and give an exhibition of their work in their homes. They nibbled at this idea of a village academy in 1951 and tried it out more thoroughly last car. From tomorrow until July 17 they hope to establish the Great Bardfield Summer Exhibition as a regular event.

At one end of the village you can find John Aldridge, A.R.A. whose traditional landscapes of the neighbouring countryside are spiritual descendants of Constable, who operated not many miles east of here. In contrast at the other end of the village (and of art) is Clifford-Smith, who goes in for a modern expressionist treatment of the human figure that is vigorous, emotional, and Mediterranean in feeling. In Clifford-Smith’s house there will also be a display of cartoons by Low, another Great Bardfielder.

In the 80 yards or so between the two houses you will find the others. Michael Rothenstein, like Aldridge, finds his inspiration round the corner. A typical Rothenstein lino-cut print shows a cornfield in which a roguish, slightly fantasticated tractor seems to be revelling in country life more than the man perched on it-who is probably working out his overtime pay.

By way of contrast George Chapman, who is in love with the mining villages of Wales, is showing a batch of paintings which, if laid end to end, would add up to the Rhondda Valley. Across the road, by the post office which is also a grocer’s and draper’s, lives Edward Bawden, A.R.A., the only one of the nine who is a genuine native.

A somewhat lugubrious looking man, Bawden cycles off in an old mac to find material for his nationally esteemed watercolours in the byways of the neighbourhood. Coming across him crouched in a ditch or huddled against a wall glumly scratching away at his pad you might take him for a private detective keeping watch on the cottage opposite. Once a suspicious farmer’s wife tipped a bucket of water over him, unaware that her house was being immortalised.

The other exhibitors are Walter Hoyle, Marion Straub, and Audrey Cruddas, who designs costumes and scenery for the Old Vic in a studio above the village café.

Charging less

B y holding the Exhibition in their homes the artists can charge up to a third less for their work, as they save the cost of transporting the stuff to London and paying the dues exacted by London galleries. For the public it is therefore a chance to pick up a future old master cheap.

What do the villagers think about it all?

Little Bert probably spoke for most of them when he told me guardedly: “I haven’t heard no complaints.” Last year, however, a few did betray their Essex caginess to the extent of being impressed by the traffic problem which the Exhibition brought to a village where normally not more than two or three cars are visible at the same time. (P.C. Plummer, whose headache this will be, is the subject of a painting by Bawden in the current Royal Academy.)

Clifford-Smith, who often plies the palette knife with generosity, treasures the remark of the retired cowman who peered long and intently at his paintings and then came up with: “Of loikes the thick ‘uns best.”

Not her idea

The women of the village have a different approach to art. One, who spent an afternoon diligently visiting every house and was then asked what she thought of the pictures, looked blank. “Pictures? Oh, the pictures! I didn’t have time to look at them. It was their houses I wanted to see.”

The landlord of The Vine, who admires all nine artists with diplomatically equal fervour, admits under pressure that the Exhibition does not particularly boost bar receipts. It seems that those who thirst for culture do not on the whole thirst for anything else. (I recall in this connection one of the empresses of the West End theatre bars once dismissing the work of an eminent but rather highbrow dramatist as “just a tea-and-ices show, dear.”)

Perhaps the hardest lot is that of the wives. Not only must they endure the invasion of their homes between 11 and 7 daily for ten days (while continuing to feed the children and appease the daily help), but they must simulate, without stopping, a fixed grin of warm hospitality.

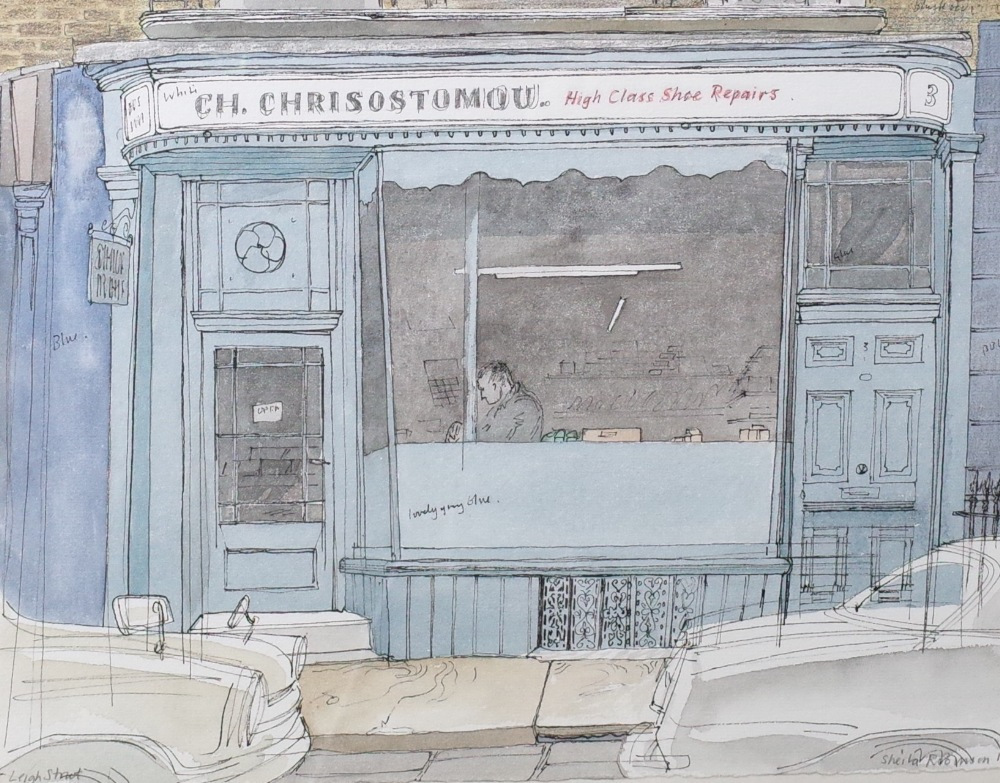

Here are two watercolours by the Great Bardfield artist Sheila Robinson. I bought them because I love both the architectural details in them, but also the typographic elements. Both of them are in St Pancras.

Sheila Robinson – 3 Leigh Street, London. High Class Shoe Repairs

In March, 1809, the Skinners’ Company built the streets around Sandwich and Leigh Street, the latter joining on to Judd Street.

Below is a painting of Sandwich Street. The building in the painting is now demolished for a set of flats. The horse drinking out of the metal bath makes me wonder if that is the home of the man who owns the cart.

Sandwich Street’s first house was built in 1812. Eighteen followed in 1813; by 1814 there were thirty and, by 1824, forty-seven.

Sheila Robinson – Sandwich Street, London.

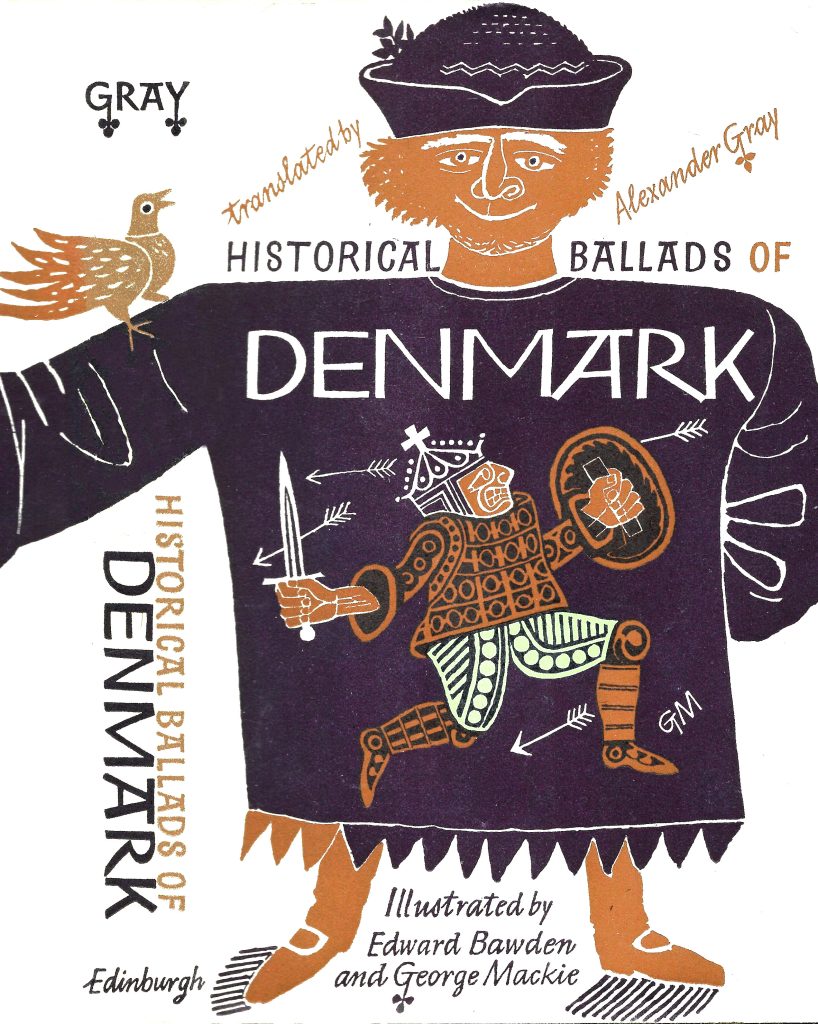

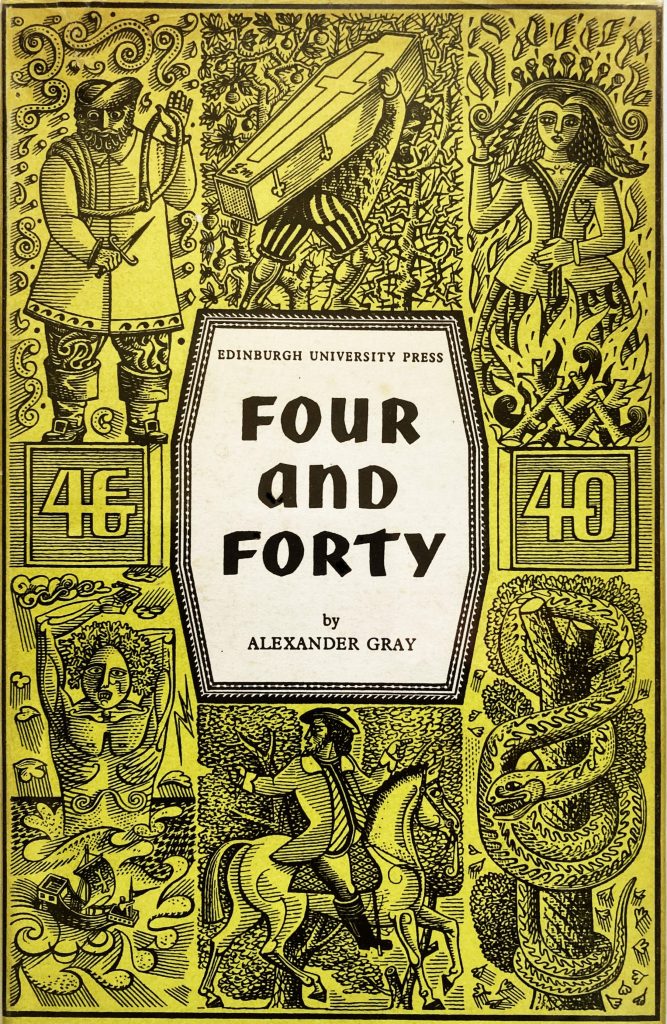

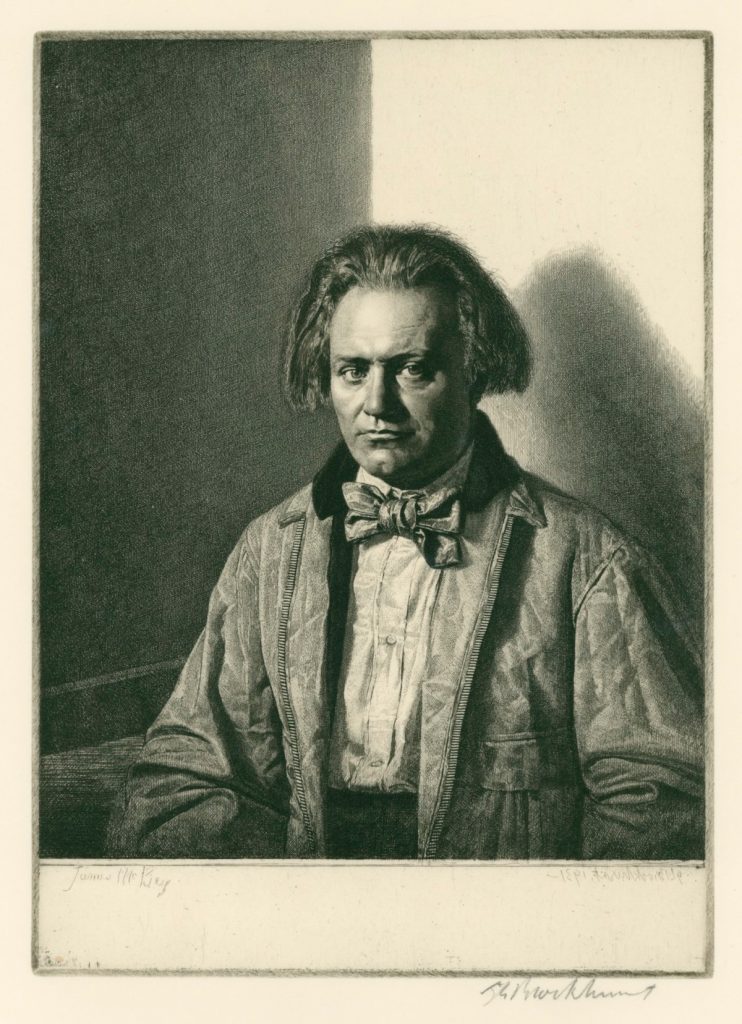

George Mackie is a lesser known illustrator. He is mostly remembered today for his book of Alexander Gray’s translations of Historical Ballads of Denmark (1958), where he co-illustrated the job with Edward Bawden.

Mackie studied at Dundee College of Art from 1937–40, then after a break due to World War II he continued his education at Edinburgh College of Art from 1946–8. He worked as an inhouse graphic designer at Edinburgh University Press, allowing him to design dust jackets and title pages of their books. At this time he also was the head of design at Gray’s School of Art, Aberdeen. his work appearing in a number of graphic magazines such as Graphis. Mackie was born in Cupar, Fife.

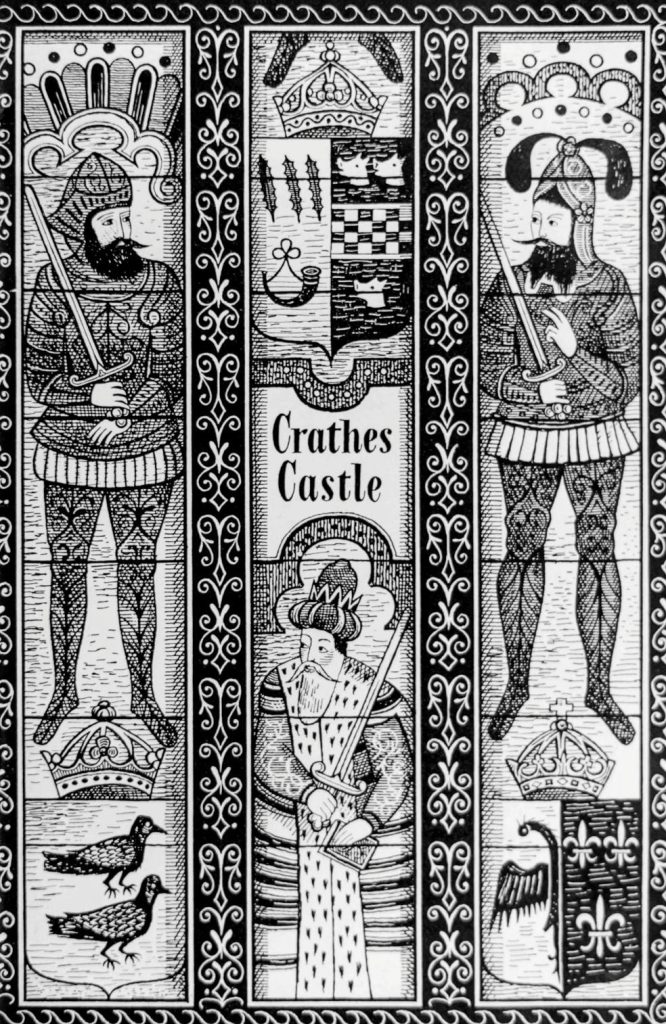

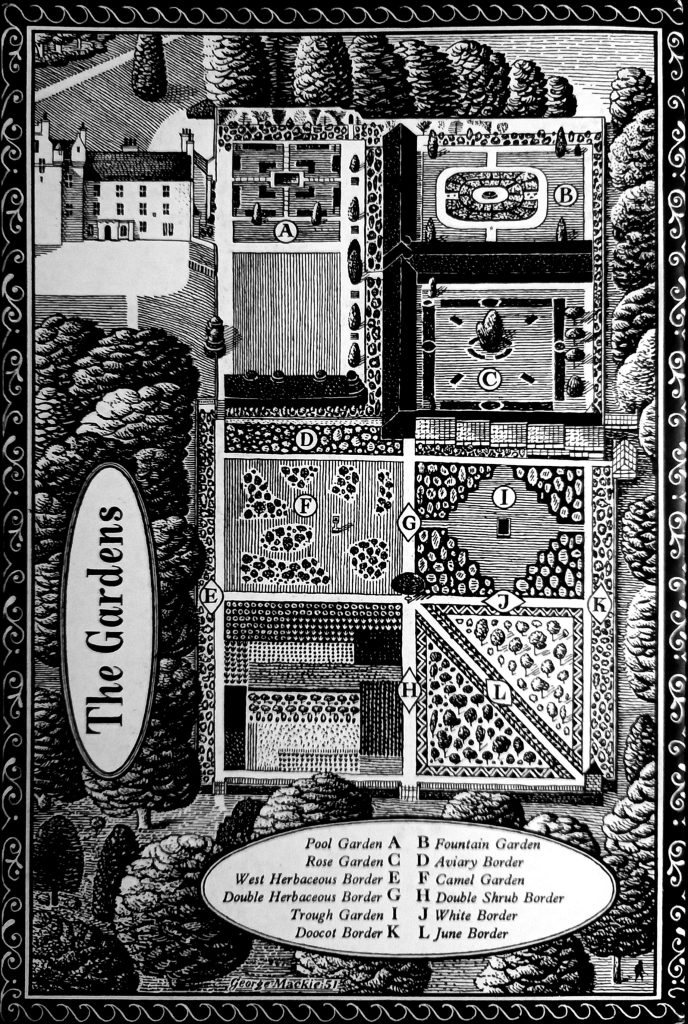

He was married to the artist Barbara Balmer. Many of his works were very pretty ink drawings made to look like wood-engravings, much in the style of Eric Fraser. This week I got a book on Crathes Castle where he had illustrated the booklet to look like a stained glass window on the front, the back of it looks not unlike Rex Whistler

This is a post about George Chapman just before he moved to Wales.

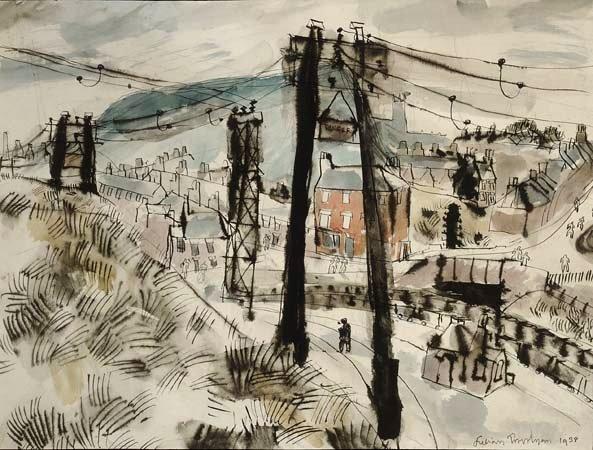

Kenneth ‘George’ Chapman was born in East Ham, London, the son of a superintendent on the London, Midland and Scottish Railway. He studied at Gravesend School of Art, and worked as a graphic designer before deciding to become a full time artist in 1937.

Chapman was one of the young artists picked out by Jack Beddington to work on a Shell poster, giving him a public profile alongside Graham Sutherland, Paul Nash and John Armstrong. At this time he was signing his work K G Chapman.

Chapman studied at the Slade for a year before Barnett Freedman recommended the painting school under Gilbert Spencer at the Royal College of Art, as the classes were freer from academic history at the RCA and also it was a college supported by the government, for artists to enter industry. Chapman then taught at the Worcester School of Art. He moved to Norwich in 1945 and married Kate Ablett, a student at Norwich School of Art, in 1947.

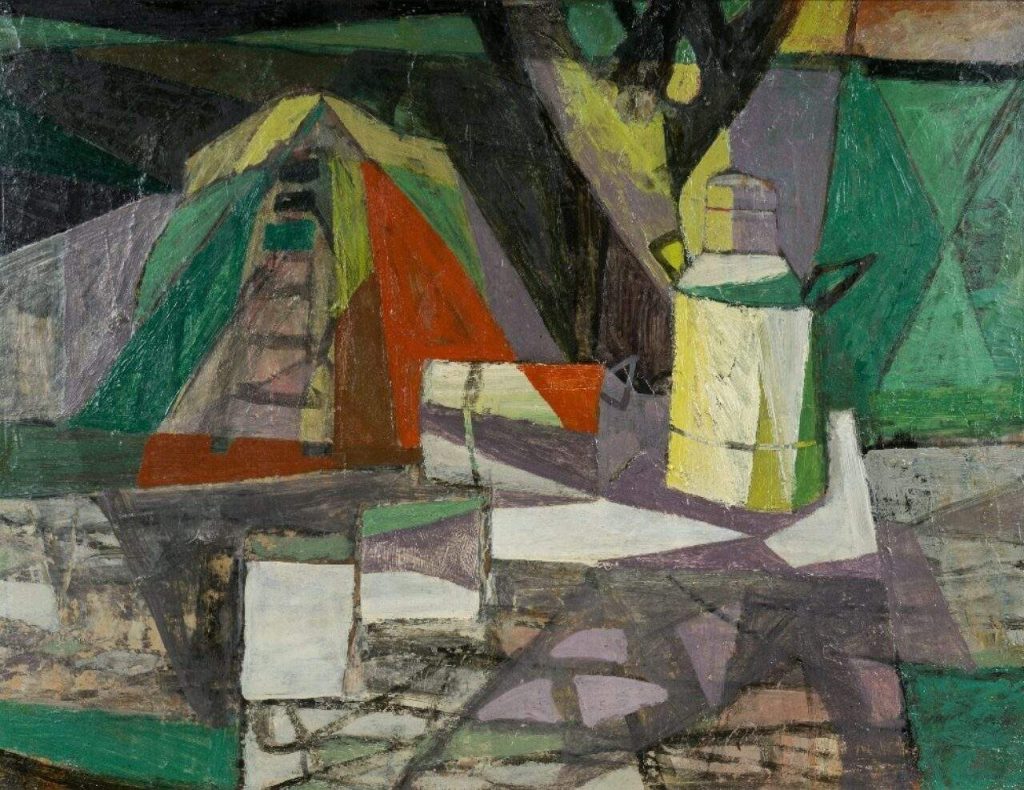

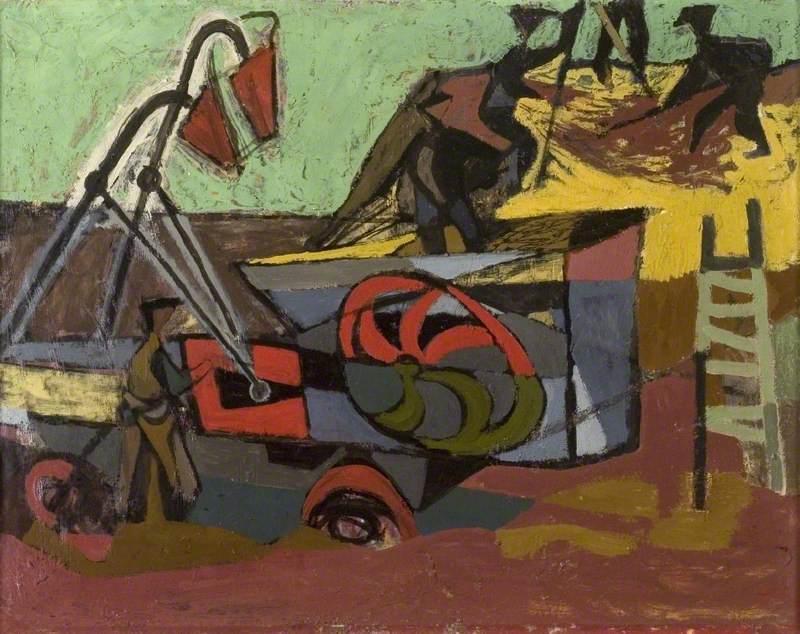

They moved to Great Bardfield in 1951 and lived in Vine Cottage and then moved to Crown House. Bawden cycled over to introduce himself and welcome them to the village. Chapman’s paintings, shown in the 1954 exhibitions, were of Welsh valleys and terraced mining towns; a contrast to the countryside around him. These early works were more expressionist, in the style of Robert Colquhoun, Keith Vaughan and other young artists.

Later he settled into a darker style of printing and etchings in dark colours, in a mood of art at the time that artists like L S Lowry were taking up. A social realism. He stuck to this style for the rest of his life.

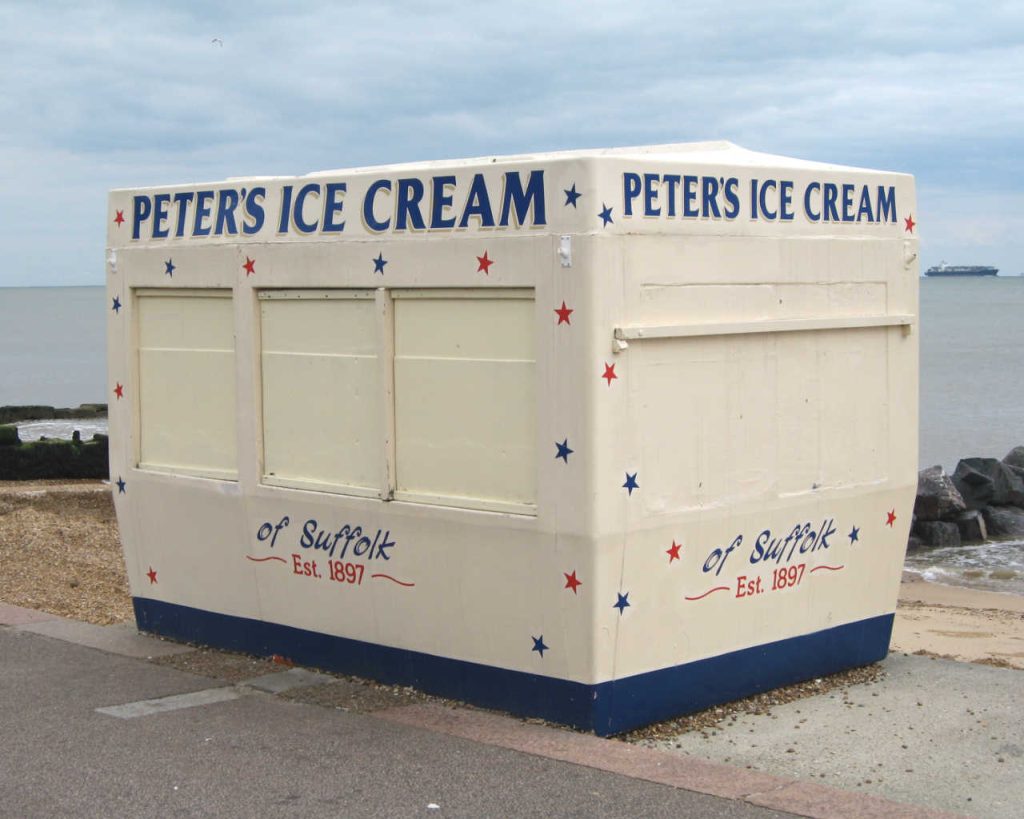

Here are some photographs of Ipswich and Felixstowe. The trip was just a venture out, but I like the bleakness of the coast that this time of year.

For some time I have been working on an Audiobook of the Lucie Aldridge book, Before & After Great Bardfield – The Artistic Memoirs of Lucie Aldridge. You can get it by clicking the image below. There is an honesty box policy with it, you can download it for free or pay what you think it might be worth. Please note, this is only Lucie’s part of the book, not the postscript.

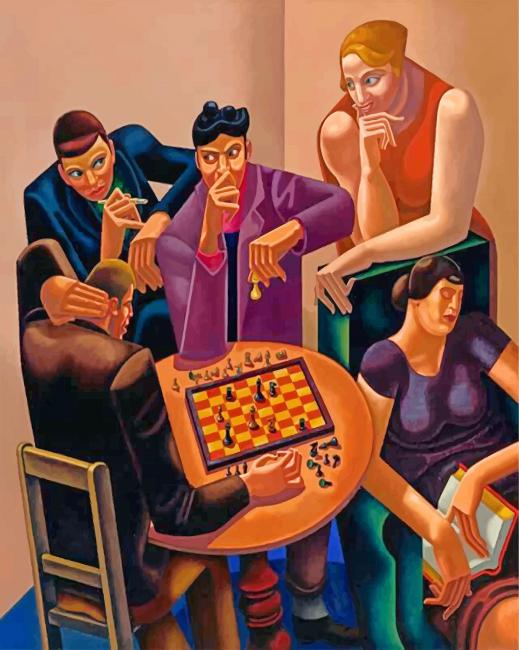

The Loan Collection of Contemporary British Art was a touring exhibition that was sent out to areas of the Empire to show the progress of British Art. The exhibition toured Australia and New Zealand in 1934.

Below is the text from the exhibition booklet, along with paintings from the exhibition. I think it is important to look at what was exhibited and presented to the world via the Art Exhibitions Bureau.

Over five years ago the idea was conceived of bringing outlying

communities of the British Empire into closer touch with “a greater

field of Art” than they, in their isolated positions, could hope for.

Apart from the many excellent exhibitions of “Fine Art” provided from time to time by commercial enterprise, we, in these distant

parts, have been, and are debarred from the pleasure of seeing and

studying those Great Works which find their homes in Public Galleries

and Private Collections of the old world.

Impressed with the great number of surplus works in Galleries

in Great Britain which might be made available, as also the hope that

National pictures might be available on loan, and the fact that

there were many public spirited private owners and Trustees of

Galleries who would welcome the opportunity to loan their treasures

for view throughout the Empire, the sympathetic support of men high

up in the Art world at Home was enlisted, and through the able and

untiring devotion of Mr. J. B. Manson, Director of the Tate Gallery,

Mr. Ernest Marsh and Mr. C. R. Chisman, the Empire Art Loan Collections Society was formed .

The names of the original members of the General Committee are sufficient guarantee that the idea struck a note which appealed to those responsible for the promotion of Art in Great Britain, and that it is being pushed with vigour against considerable handicaps.

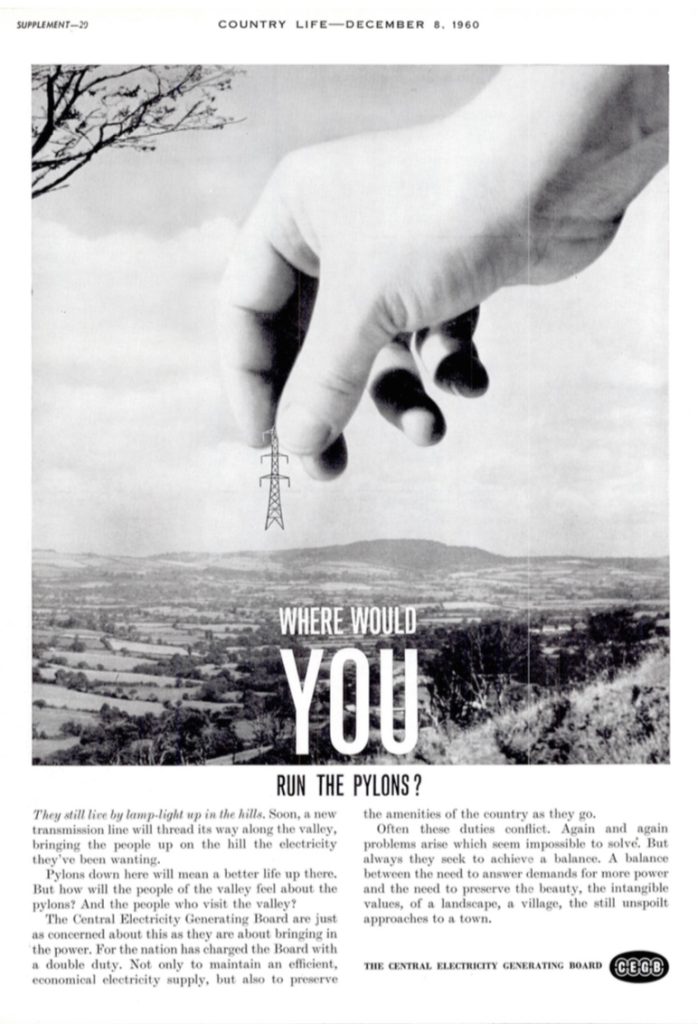

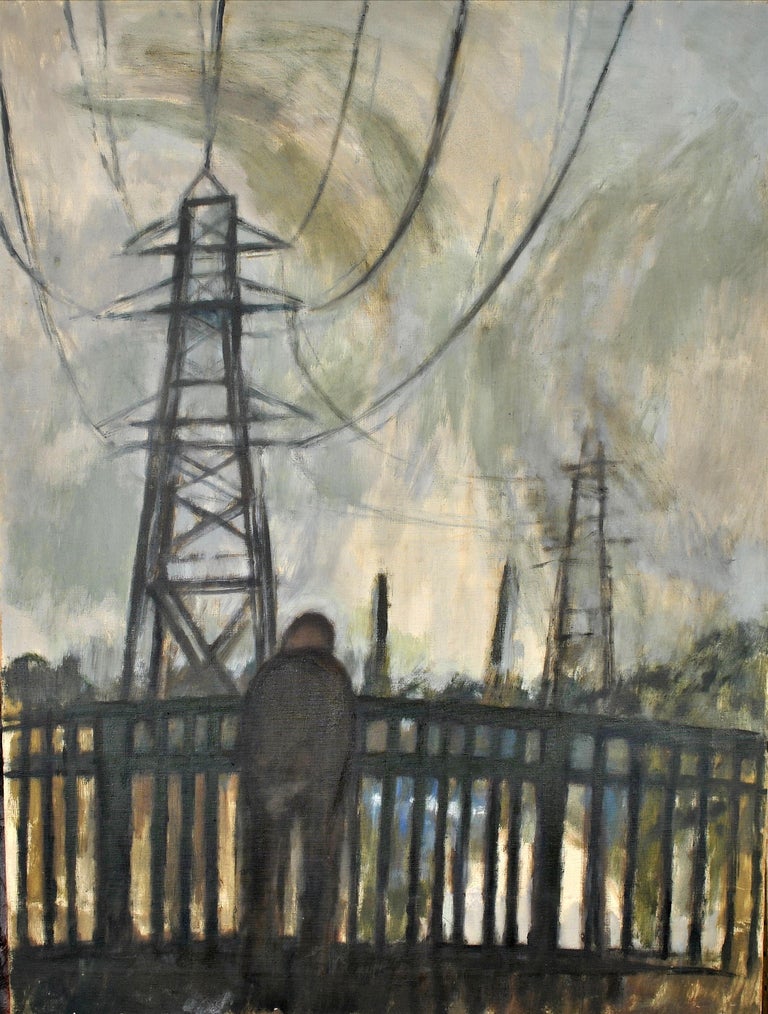

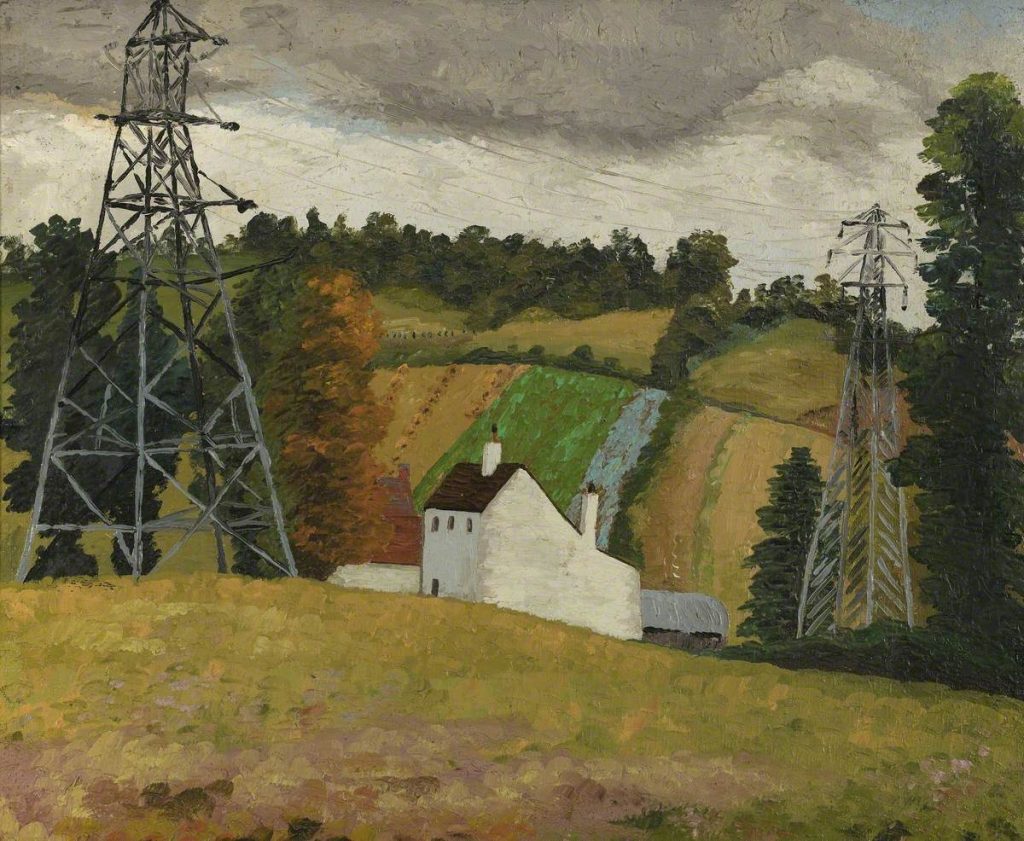

The standard design for pylons in Britain was chosen by a competition run by the Central Electricity Board in 1927. It was won by Sir Reginald Blomfield often gets the credit for the ‘lattice’ design. But the design was improved so it used less metal..

I used to have arguments with an ex, about Pylons. He saw them as majestic marvels that give us power. But I found them to be blots on the landscape. Anything man made on the landscape removes us from the beauty of nature. So this blog looks at artists who painted pylons as the marvels of the age.

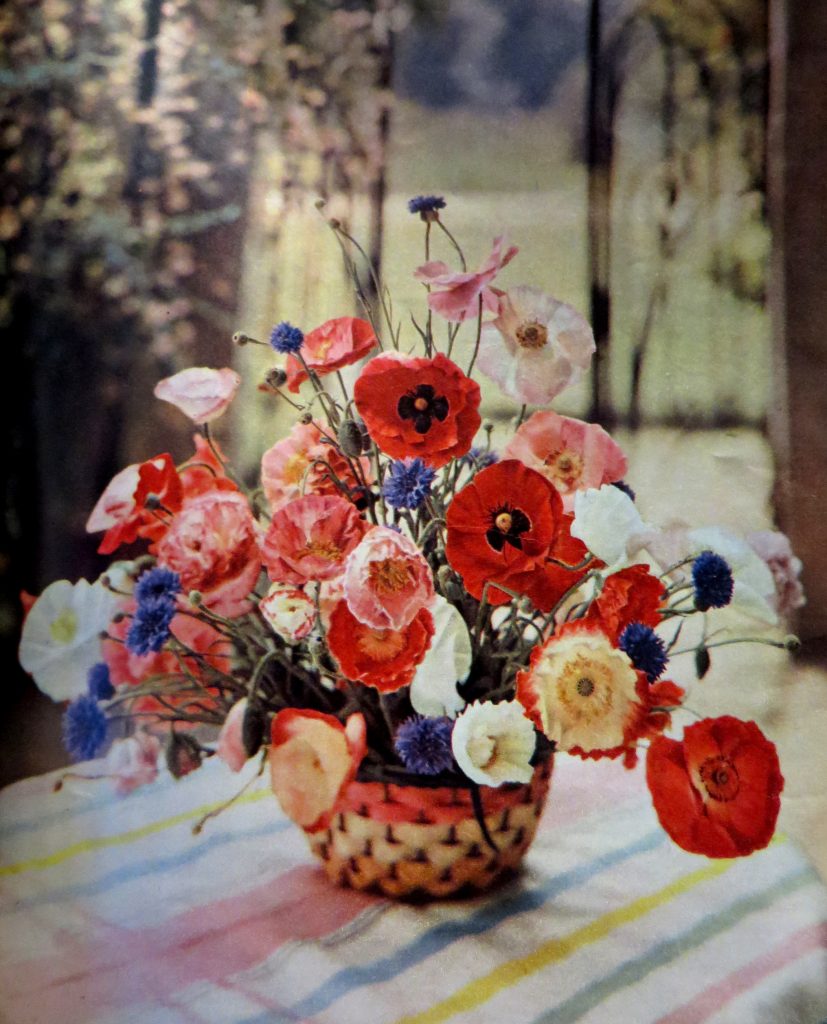

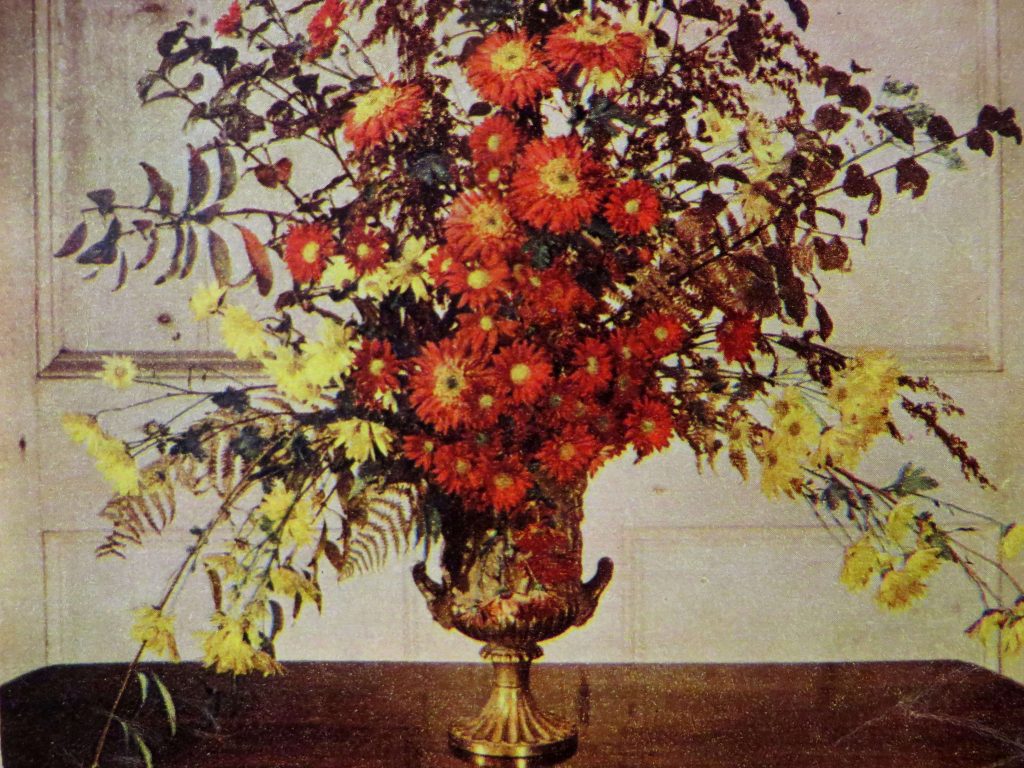

Many years ago I planned to do a blog post on Constance Spry but never got around to it. I found the photos the other day. I think they may stand for themselves in how revolutionary her style was. From stripping a branch of fruit of the leaves and leaving; to her vases of traditional wild flowers.