The Omega Workshop was opened with members of the Bloomsbury Group and headed by Roger Fry. It was an attempt to celebrate handmade items, without being too rooted in the Arts and Crafts tradition. Though the link is undeniable, the decorations of the items was not precise and Omega was more like the British version of the Mingei movement that happened later in Japan. On visiting the Omega studios in 1913 Yone Noguchi noted that Roger Fry was “attempting to create an applied art just as (William) Morris did” and that the studio was using Cubist motifs and designs, of abstract shapes in the fabrics and wood marquetry. The shop and workshop was sited inside a building on Fitzroy Square. But with no shop window promoting the wears the studios relied on magazines and word of mouth to promote themselves.

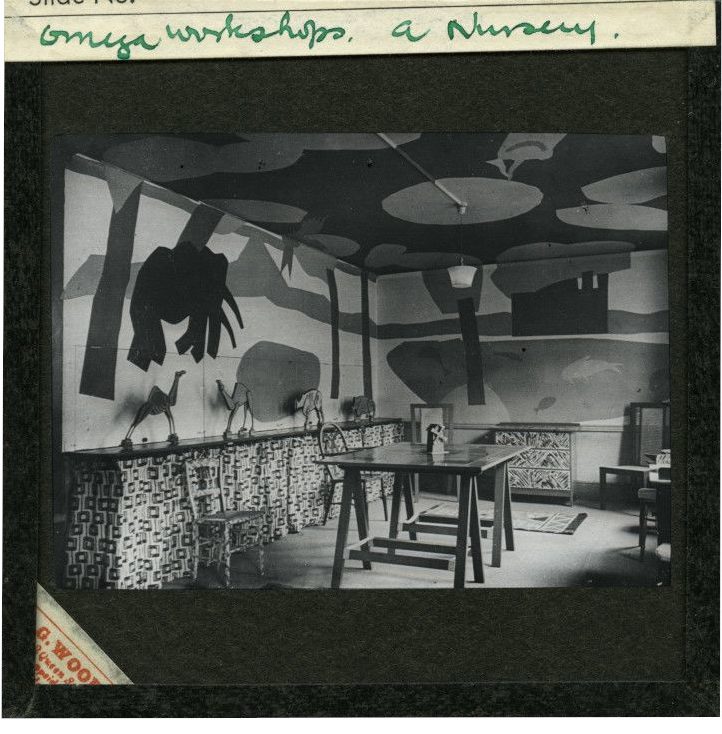

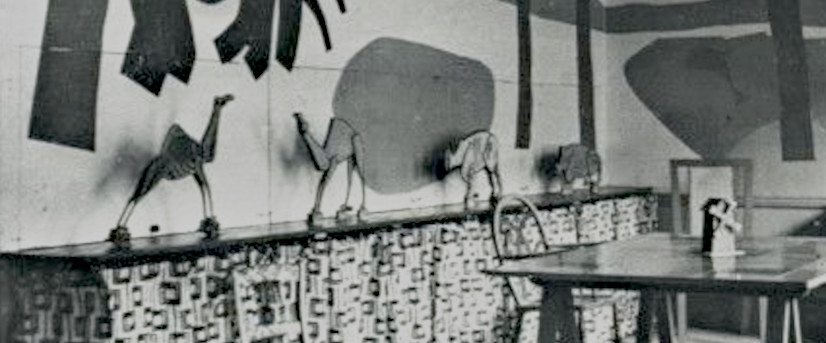

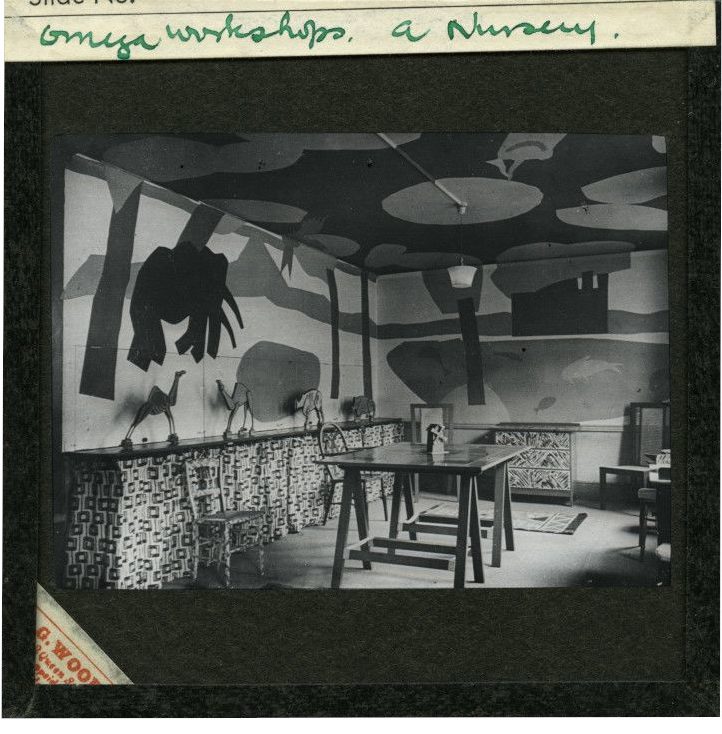

The early output of the workshops were far more open to the hope of public success. When in December 1913, there was an exhibition of their recent work at their Fitzroy Square building it included a nursery for members of the public to view. With shelving covered in fabric and wooden toys painted standing above. A toy windmill sits on a painted table and decorated chairs. Today, we might not see this as a shocking looking room, it looks like any primary school or day-care centre. However in 1913 it was as wild as radical as you could get. This was an age were schools looked more like prisons, wooden benches and white walls.

The nursery wall had panels by Vanessa Bell which she believed were ‘a most truthful portrait of Indian and African animal life’, with elephants and tropical trees and decorative watering holes. While the ceiling was painted by Winifred Gill with tree foliage to match Bell’s designs. Not pictured in the photograph above was Roger Fry’s doll’s house (see below).

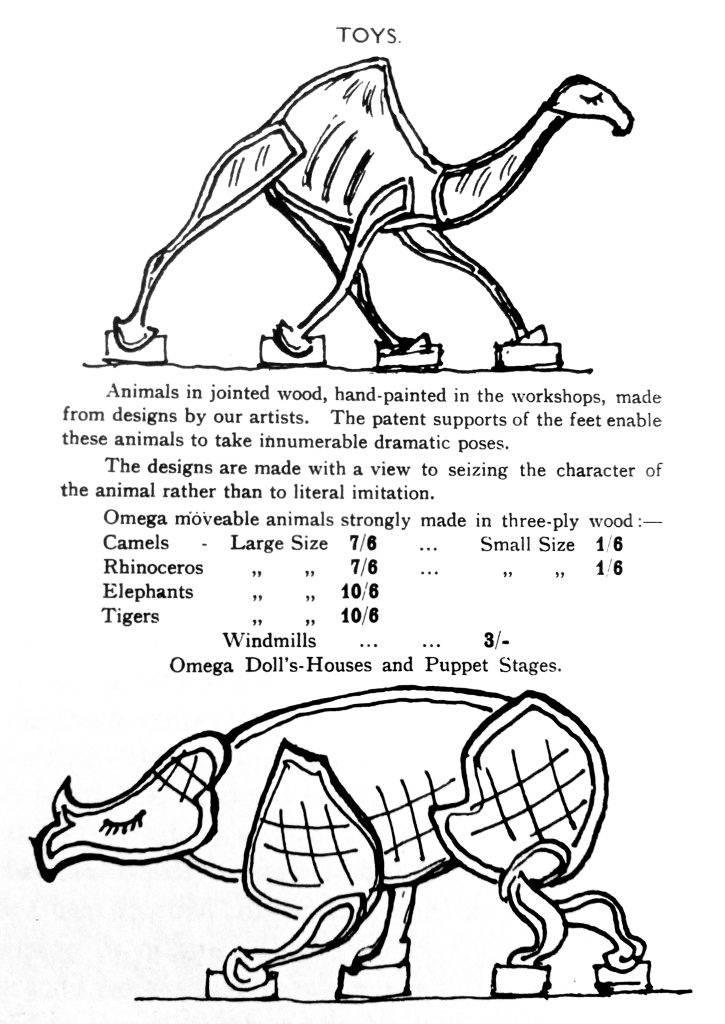

Above and below you can see the designs and end product of the Bloomsbury scratch built animals, with hand painted finish. They were crude, but many toys of this age were, and they had movable limbs. The design below comes from the original sales catalogue that Omega gave to willing parents able to afford such toys.

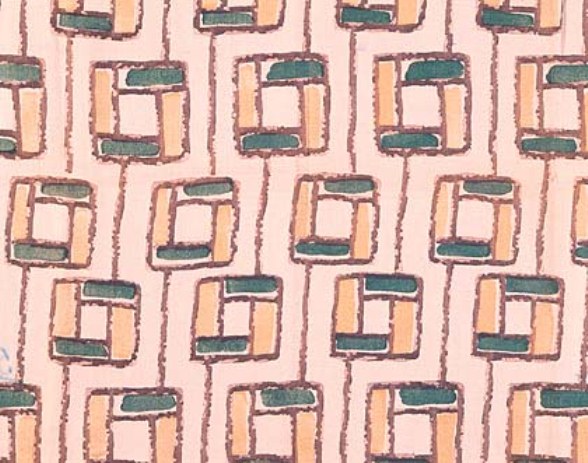

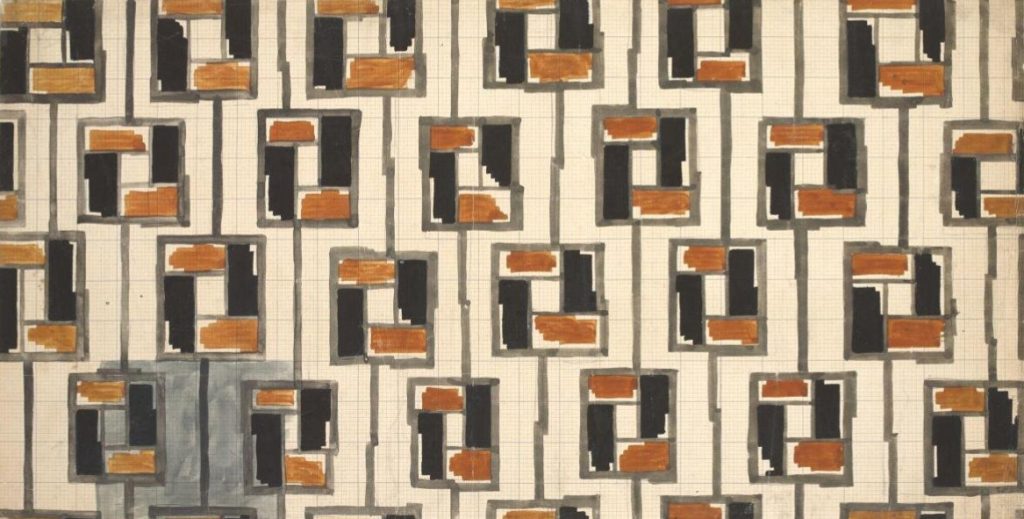

The slide above also shows the shelving cover. Below to the left, is a sample of the finished fabric, and to the right the original design. Opinion on who designed what at the studio seemed to be mixed, as the interest in the Omega studios output was only kindled in the 1970s long after Etchells and Fry’s deaths. But it is believed one of them designed it.

Below is the dolls’ house designed by Roger Fry. It is thought to be a stylised version of this house near Guildford in Surrey and had hinged flaps for the children to open and play with.

It is unknow how many were sold, but it is likely the numbers are very low. However, the universe being what it is, you never know when one might turn up.

In 2030 Charleston in East Sussex is set to celebrate 50 years since the charity was set up to safeguard the historic and its collection of Bloomsbury art and decorative art.

Next week at the London Art Fair, Charleston launches an ambitious search for 50 of the most significant Bloomsbury group art still held in private collections. The hope is that through generous gifts and legacies these important and unique objects will will become part of Charleston’s extensive collection and reunited with what is already the largest collection of Bloomsbury group artworks worldwide. The launch of ‘50 for 50’ will take place at the London Art Fair in January when, as the fairs Museum Partner for 2024, Charleston will unveil a selection of secured artworks alongside some of the most significant pieces from its collection.