Category: Uncategorised

The Midland Regional Group of Artists and Designers was founded by Evelyn Gibbs in 1943. Gibbs had studied at the Liverpool School of Art and at the Royal College of Art, before winning a Prix de Rome scholarship for engraving in 1929, with which she spent two years in Italy. Supporting herself by teaching at a school for handicapped children, she wrote a book (The Teaching of Art in Schools, 1937) on art teaching illustrated by her pupils, and then became a teacher-training lecturer at Goldsmiths College. When Goldsmiths was evacuated to Nottingham during World War II, Gibbs created the Midlands Group of Artists. After they had two exhibitions in a large empty building, they were able to move into a permanent gallery and a range of other activities supporting artists in the region.

The interest of Goldsmith’s pupils locally would provide students with commissions. One of these was for a mural in St Martin’s Church, Bilborough – This mural was completed and then covered over when the church was modernised in 1972, only to be discovered in 2009, cleaned in 2013 and funding provided for restoration soon after.

The first Chairman of the Midland Society was Hector McDonald Sutton, Principal of Mansfield School of Art and the main volume of members were from local art schools. The group became an affiliated member of the AIA in 1943 with the first exhibition with the AIA in Henry Barker’s department store. By the 1950s they were partly sponsored by the Arts Council of Britain and got money from their Festival of Britain scheme for local communities.

It was arguably the most significant organisation involved in the presentation of new art in Nottingham and its East Midland environs until its demise in 1987… Not only did local professional artists exhibit at a variety of locations within the city but fortunate attendees saw the works of international artists. … During the Group’s heydey in the 1960’s (now) world famous artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, David Hockney, Gerhard Richter, Paula Rego, Bridget Riley, Robert Mapplethorpe and the already renowned Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray were shown.

Artist Biographies – The Midland Group.

After 1987 the Group became broader with theatre involved and rebranded itself as The Midland Group.

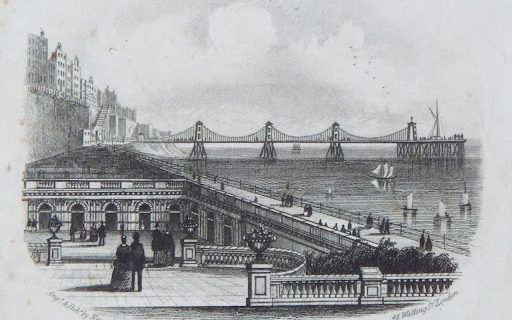

Joseph Mallord William Turner – The Chain Pier, Brighton, 1824

The Royal Suspension Chain Pier was the first major pier built in Brighton, England. Built in 1823, it was destroyed during a storm in 1896.

Generally known as the Chain Pier, it was designed by Captain Samuel Brown rn and built in 1823. Brown had completed the Trinity Chain Pier in Edinburgh in 1821. The pier was primarily intended as a landing stage for packet boats to Dieppe, France, but it also featured a small number of attractions including a camera obscura. An esplanade with an entrance toll-booth controlled access to the pier which was roughly in line with the New Steine. Turner and Constable both made paintings of the pier, King William IV landed on it, and it was even the subject of a song.

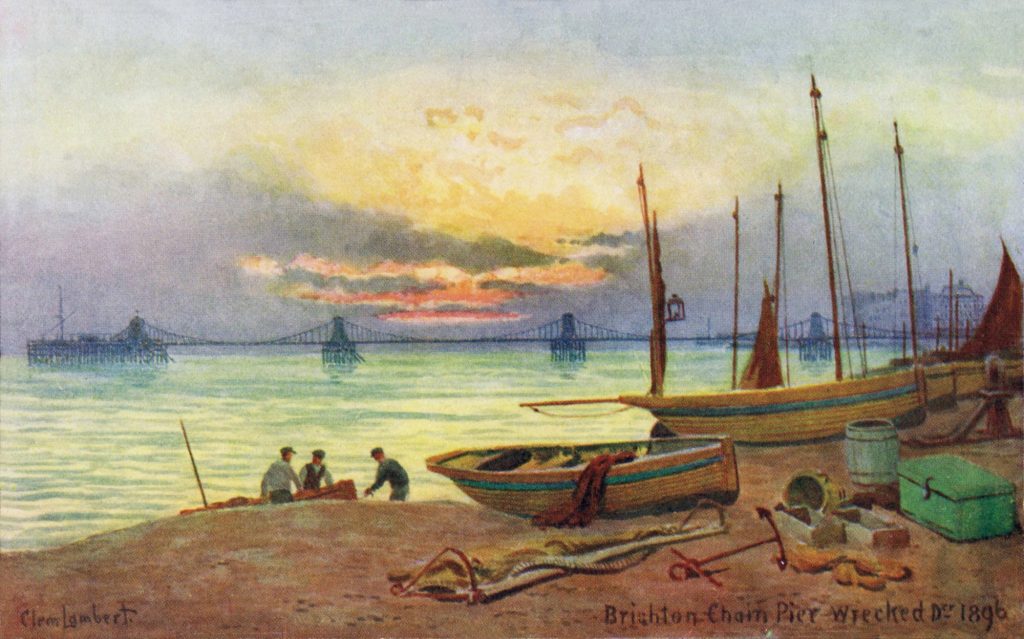

The Chain Pier co-existed with the later West Pier, but a condition to build the Palace Pier was that the builders would dismantle the Chain Pier. They were saved this task by a storm which destroyed the already closed and decrepit pier on 4 December 1896.

John Constable – The Chain Pier, Brighton, 1824-1827

The remains of some of the pier’s oak piles could be seen at low tides around 2010, however, as of 2021, they are no longer visible. Masonry blocks can still be seen. The signal cannon of the pier is still intact, as are the entrance kiosks which are now used as small shops on the Palace Pier.

Joseph Mallord William Turner – The Chain Pier, Brighton, 1828

In this post I thought I would look at something lesser known, the colour photographs of Angus McBean, from later in his life. Below is a wonderful example of him revisiting his past.

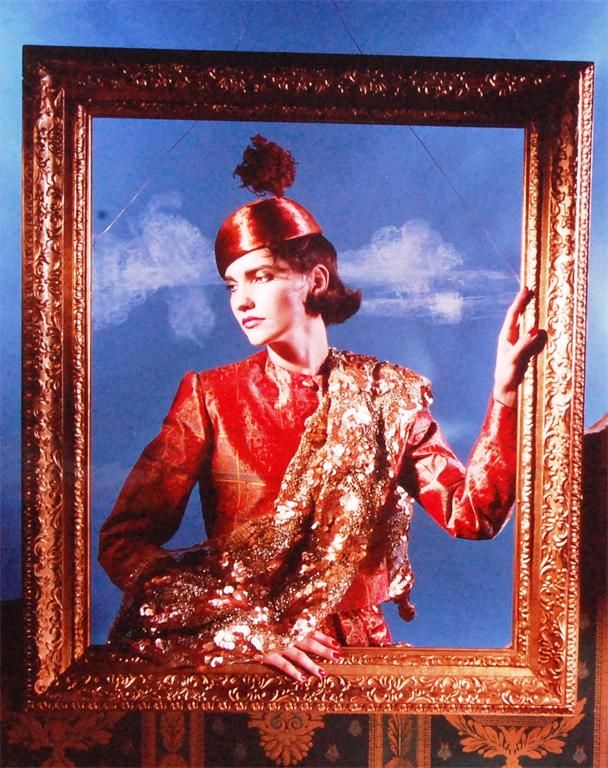

(Right) Angus McBean – Mode pour Jean Patou, publié dans L’Officiel, 1983

In his later life McBean worked for magazines in the 70s and 80s making similar images but with a more commercial angle.

I think if some of these photos are a little mundane it might be because of the art directors of the magazines rather than McBean himself, but he uses the clothes to be promoted and still makes them interesting. The most constant link in them all is the back-curtain, giving the images a theatrical look, while the poses are pure Gainsborough.

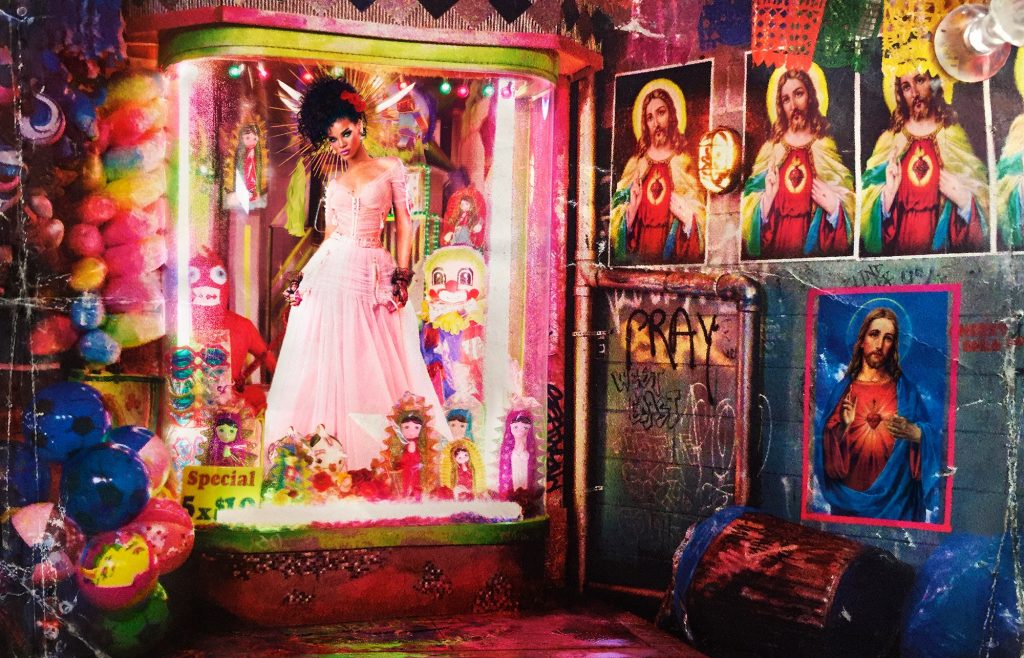

These later works of McBeans in colour are only a few steps away of a gaudy and fabulous onslaught of David LaChapelle who takes low culture items and places them into hyperreal scenarios.

From the Plague Journal – 30/05/2021

To many the plague and black-death was long ago, in a distant time. In the medieval period it hit Europe many times. For the modern world the freedom of international travel was our downfall, with Covid-19 spreading all over the world, we see the same with random variants across the country.

The same was true of the bubonic plague, spread by boat and trade caravans across the world. In 1897 an epidemic travelled from Yunnan in China, to Hong Kong and India via ship. That caused it to become international in all the major trade ports of the East India Company or anywhere trading in silk, cotton, spices, tea, indigo dye or opium.

What people might not know is that the plague came to Britain in 1910, mostly to East Anglia. Starting in the area around Ipswich, a child became ill first, with flu like symptoms. The household and neighbours were ill in the next week, each person only surviving three days. Their funerals were held in the open air and the mourners had their clothing disinfected. It’s all too familiar. The 1910 plague likely came about because the port of Ipswich was a busy industry and many people moved to and from the docks. Also being an arable landscape, there was plenty of food for the rats as many of the epidemics happened during the harvest, gleaming off the crops. Back then the rat population used to grow to quite large numbers, until the local councils employed rat catchers.

The same experts who worked on the plague in 1887 in India were called in for advice and expertise, in those investigations over fifteen thousand rats were killed and dissected for examination.

Other than the local rats being caught was other wildlife, including a hare also found to be infected with plague. A sailor who had cut himself while preparing a rabbit he had caught, also contracted the plague and took the illness to the village of Shotley. How did it transmit itself if there were no major outbreaks elsewhere, no one really knows. The idea was that rats or fleas (xenopsylla cheopis) on ships or in the sacking from the ships provided the substance for these outbreaks and they affected mostly rural families.

Other than an outbreak again in 1918 in Suffolk there have been few cases in Britain since. The atrocities of the First World War and the Spanish Flu have erased the memory of this, but it isn’t so long ago. In 1994, a plague outbreak in five Indian states caused an estimated 700 infections (including 52 deaths) and triggered a large migration of Indians within India as they tried to avoid the plague.

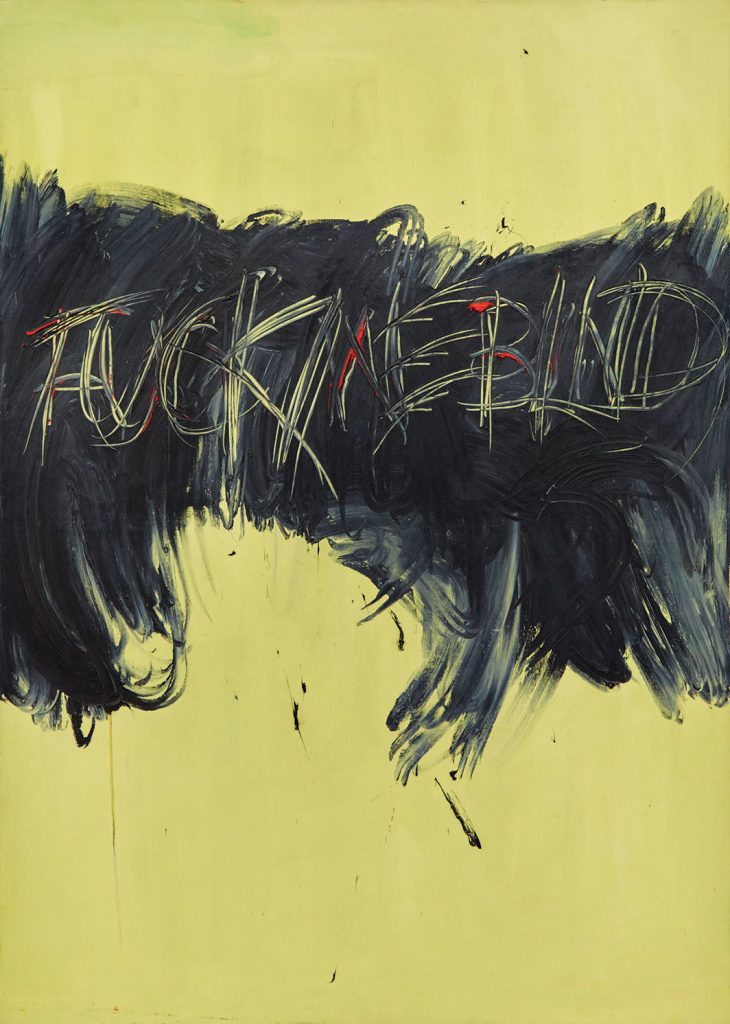

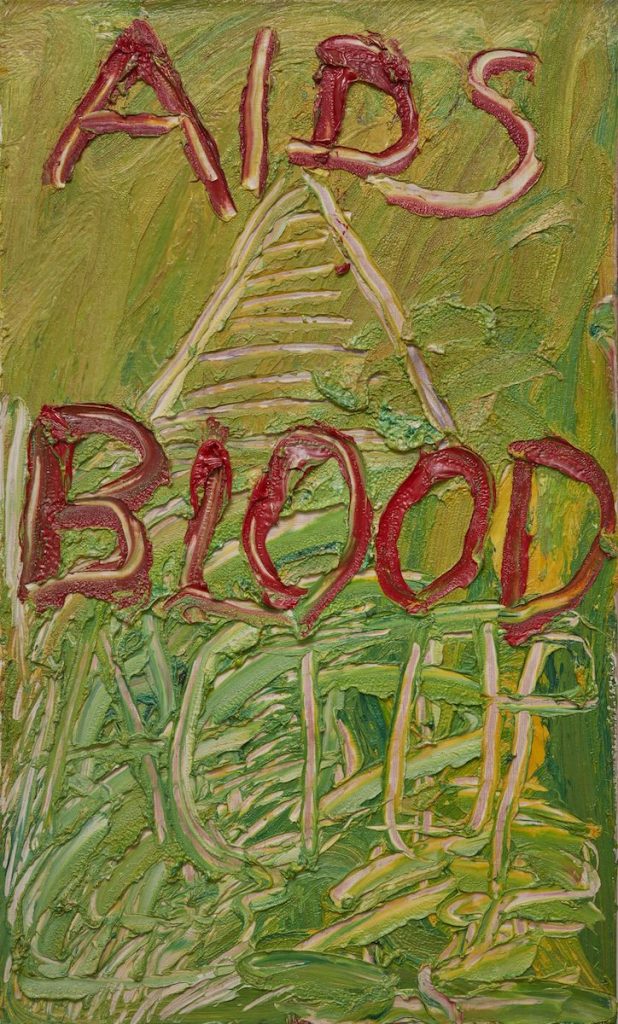

It is known that Jarman’s works later in life where large canvases of simple slogans. To promote awareness or to shock people into action? Well likely both – though at my school we had no sexual health education at all.

Jarman was diagnosed as HIV-positive in December 1986 and on medication that had no known effectiveness, he would have been sure his life was limited every morning. These days, people have PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) they can take and either have safe sex and not catch HIV or, have HIV and not transmit the disease on to others with PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis).

In 1992, Jarman was working with assistants to produce a vast amount of work, as part protest and part legacy. In an interview Jarman noted that it was very hard making movies in a system that needed public funding under a homophobic tory government and a right wing press. A result of his HIV status, Jarman lost his eyesight and went blind leading him to make his movie Blue.

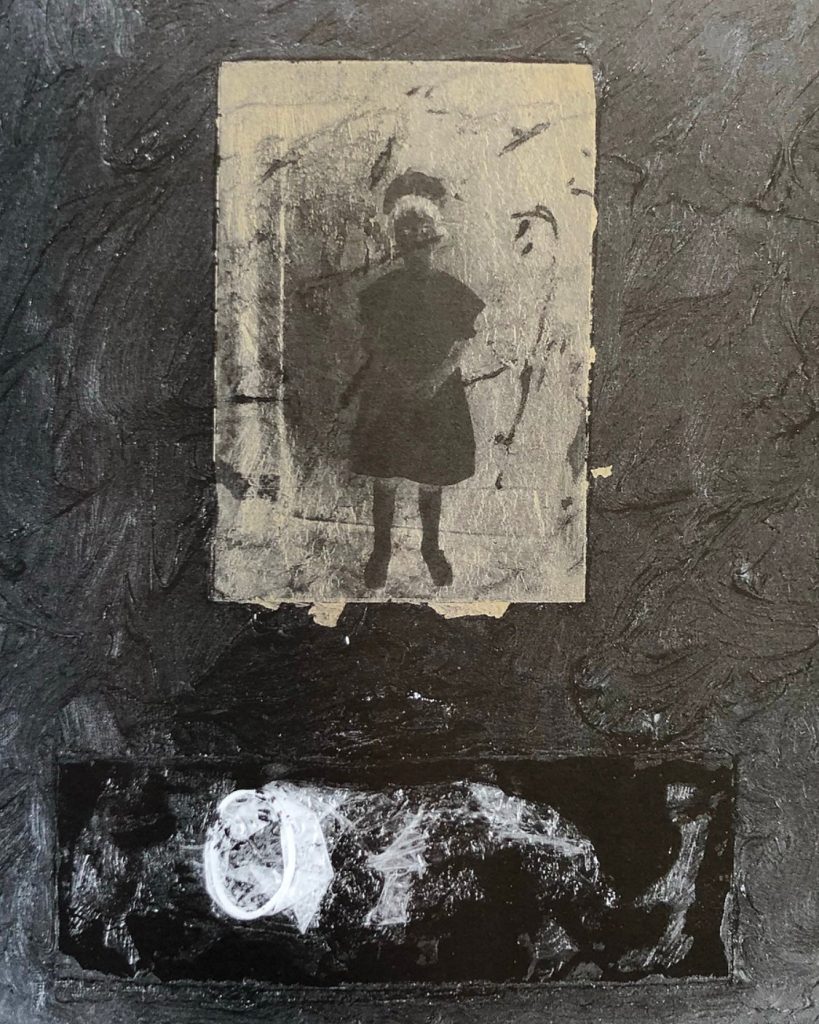

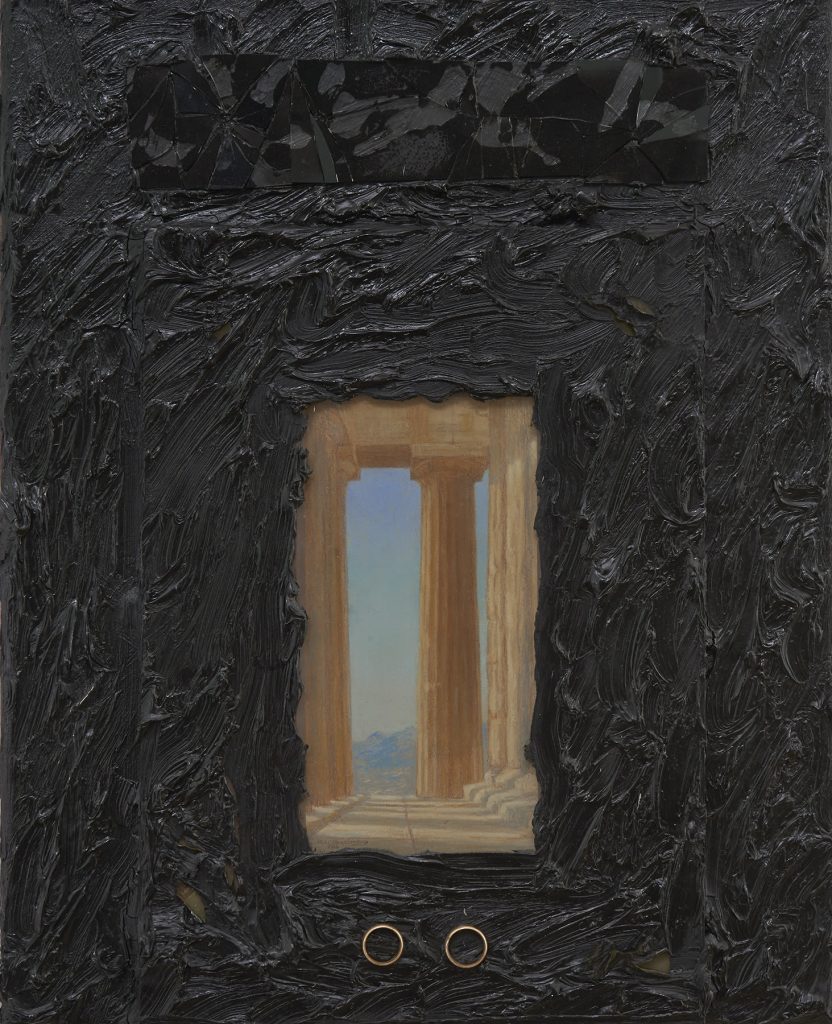

These images below are made up of many religious icons, such as broken icons, nails and crosses. Most of these are roofing bitumen, oil paints and found items. Whenever a mirror can be broken it is. What this all could mean is likely a many levelled response. Having HIV that was turning into AIDs, it might have been about the darkness and futility of life, but this might also be my perspective of his mind. Below are some of the most compelling works from the Luminous Darkness exhibition .

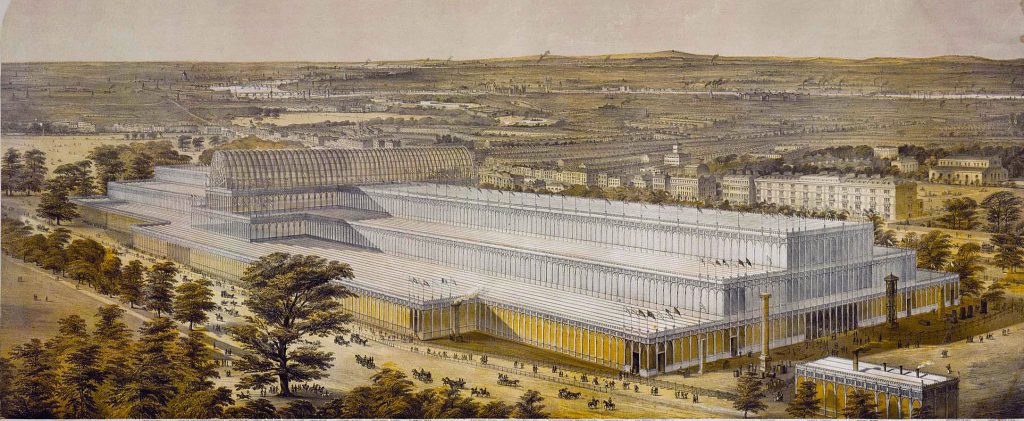

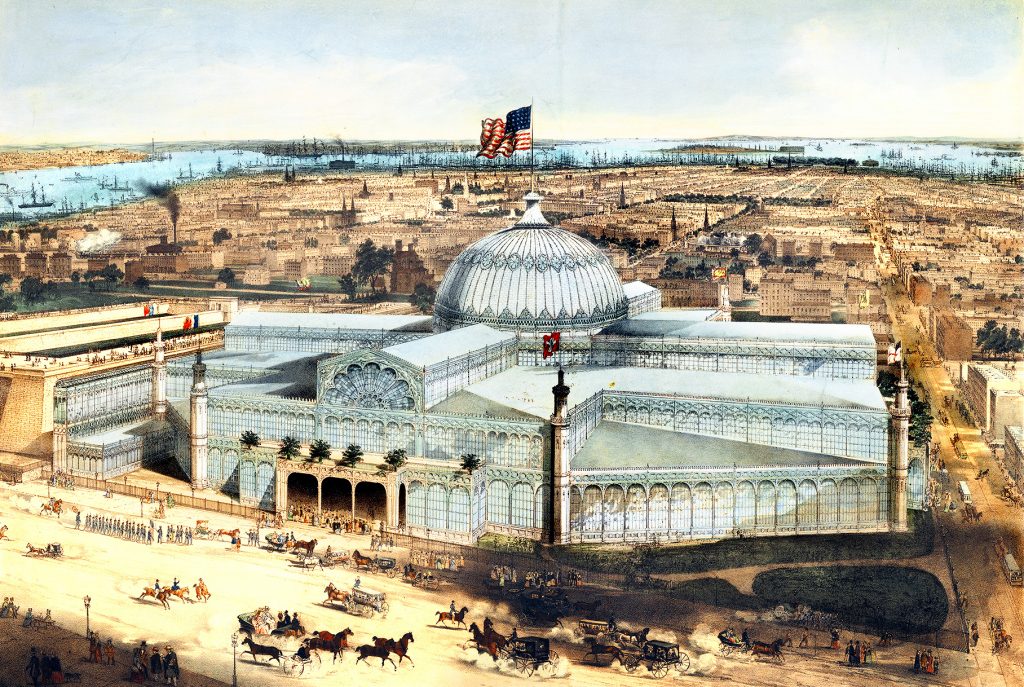

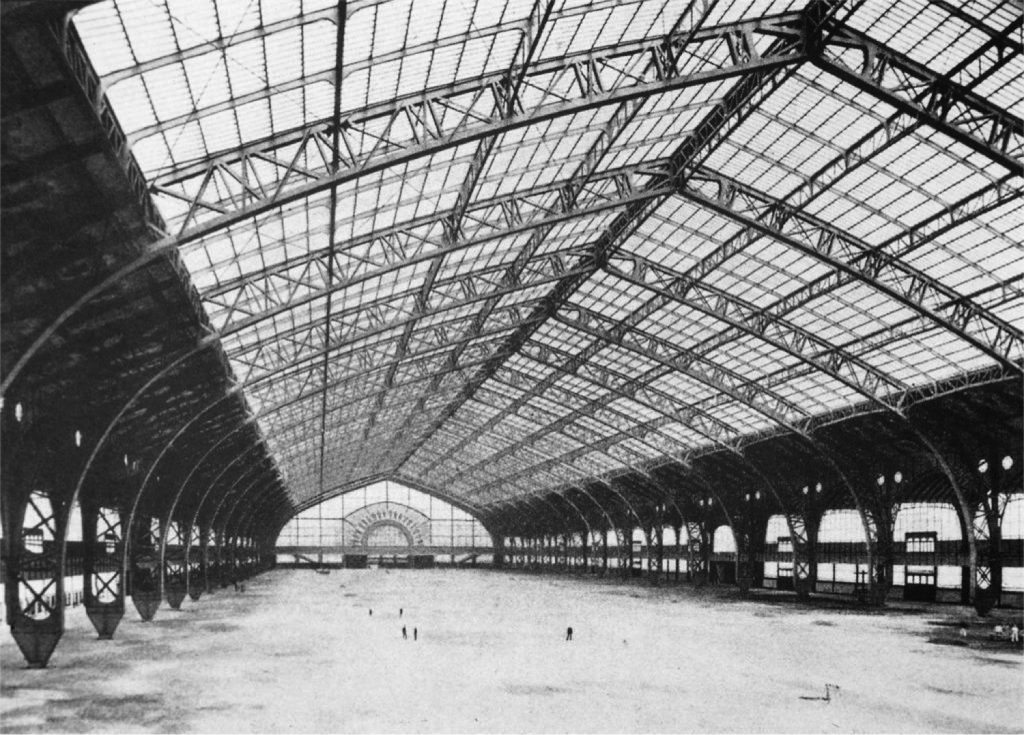

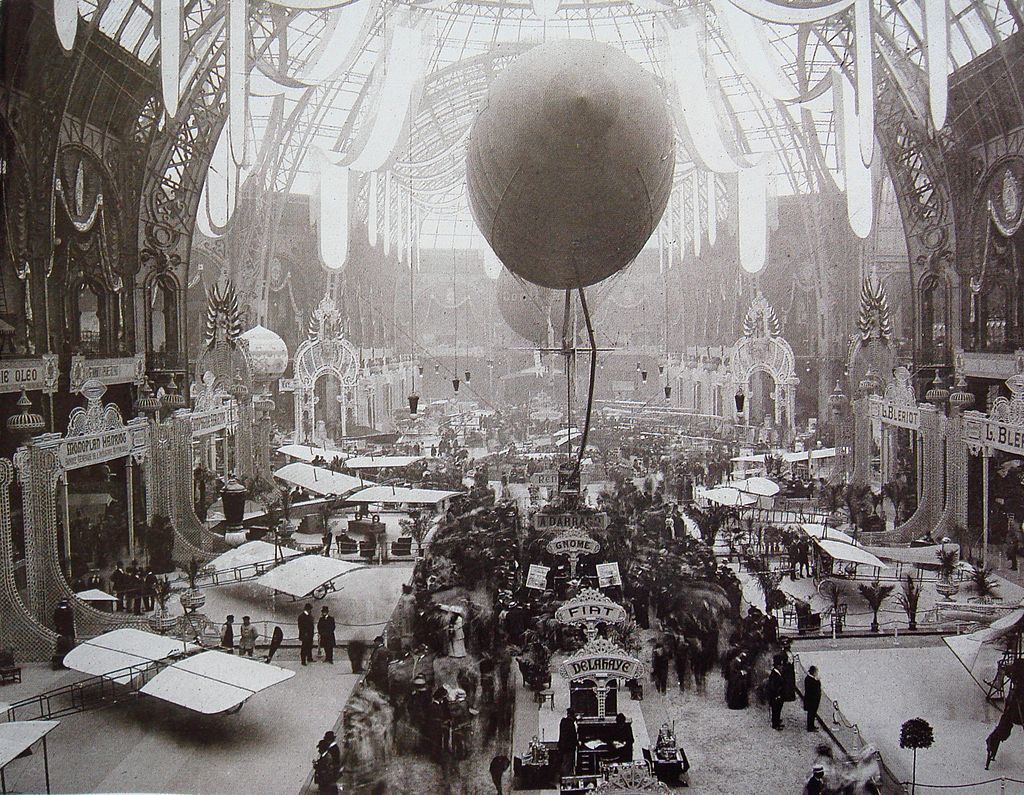

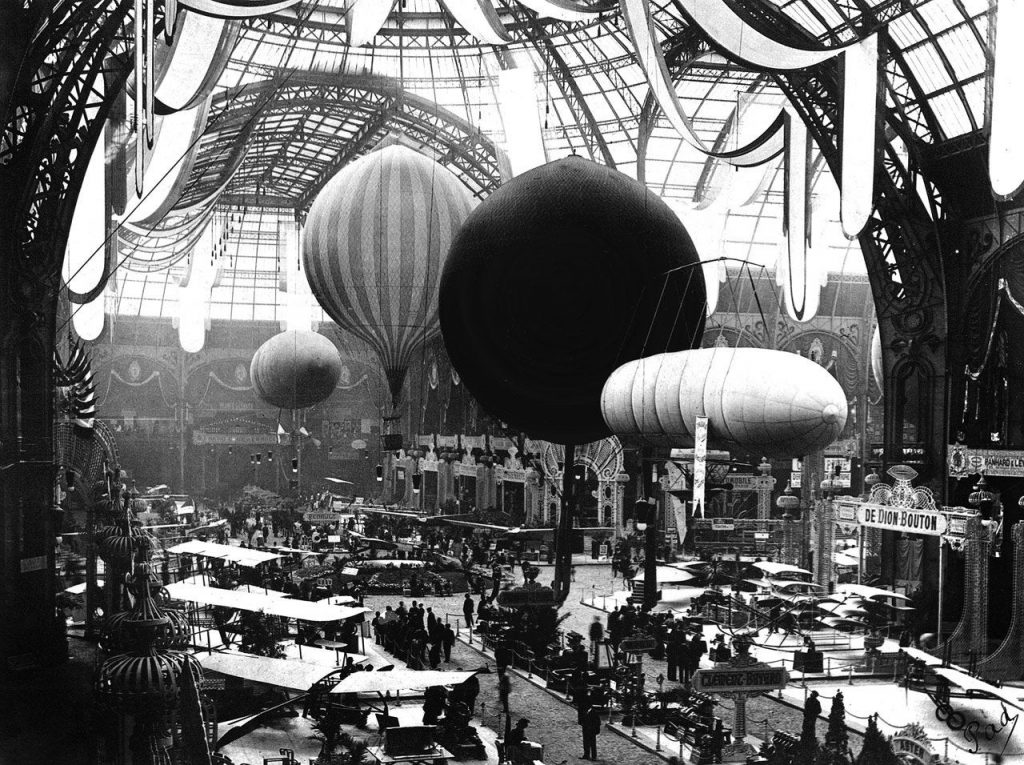

Universal Exhibitions took place all over Europe, with every nation trying to outdo the next. The start of the mania was the 1851 Exhibition in London, where the Crystal Palace, a palace of glass and metal, struck everyone with its transparency, its vastness and its construction techniques. This was one of the first modular buildings that could be manufactured quickly with universal parts. The Crystal Palace had its own viewing platform when they took command of an old shot tower.

- London – Crystal Palace, 1851

- New York – Crystal Palace, 1853

- Paris – Palace of Industry, 1855

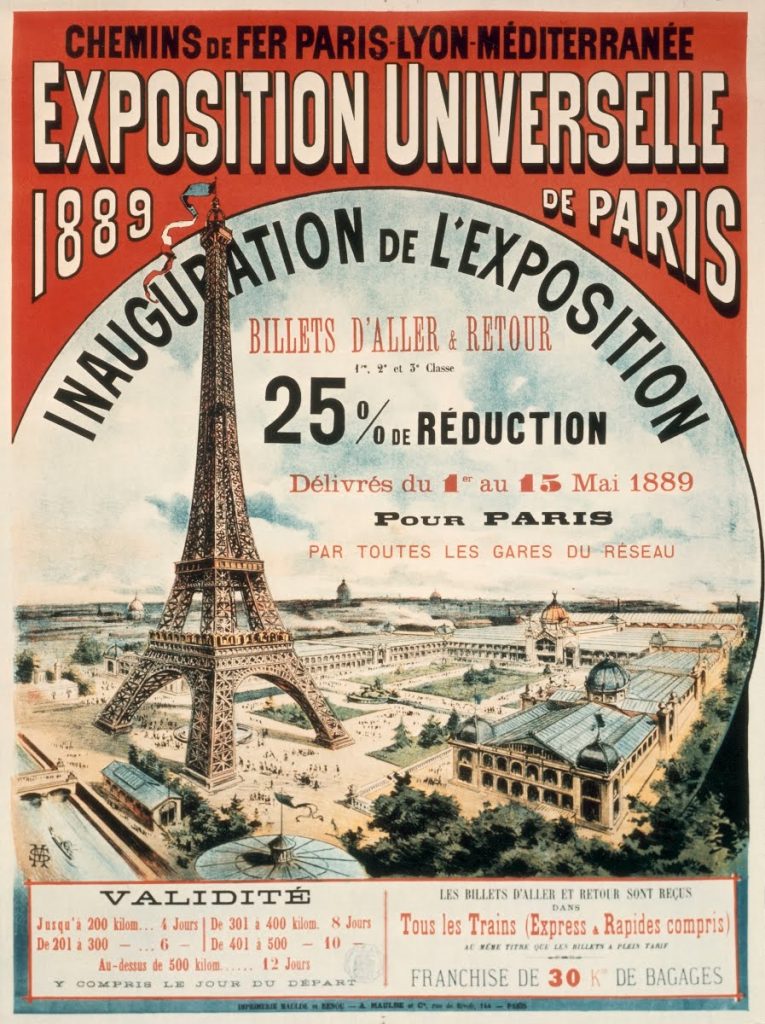

- Paris – The Exposition Universelle of 1889 (Eiffel Tower)

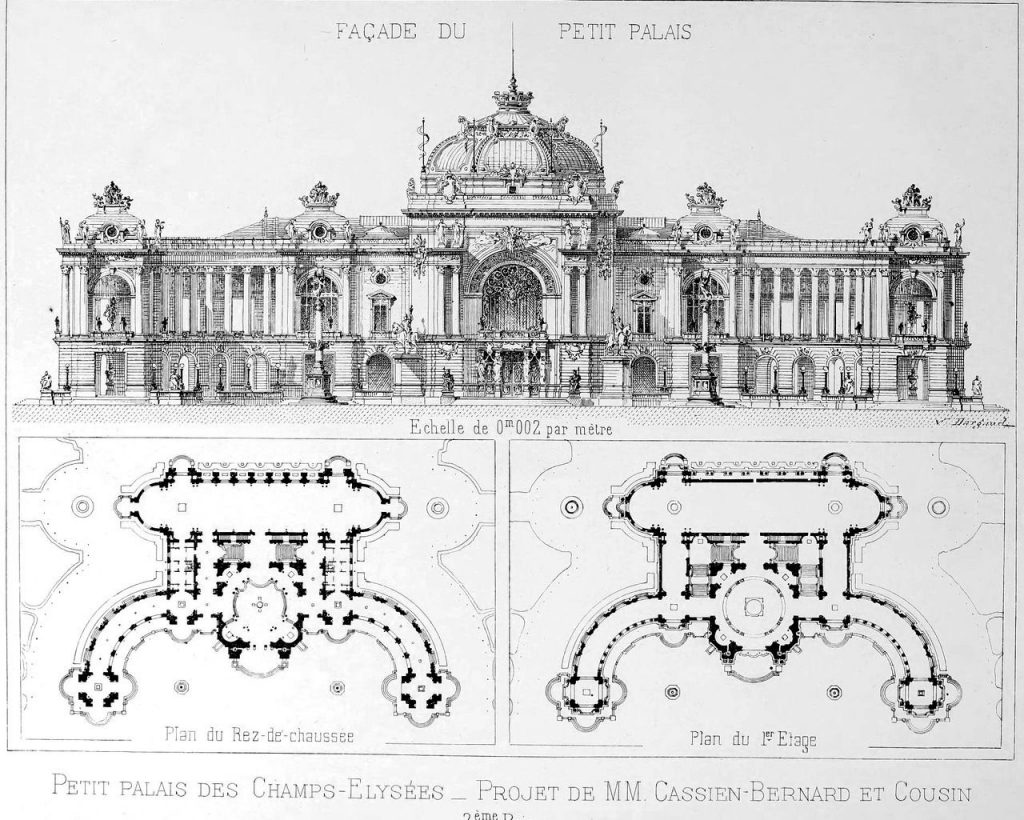

- Paris – Grand Palais, 1900

1851 London

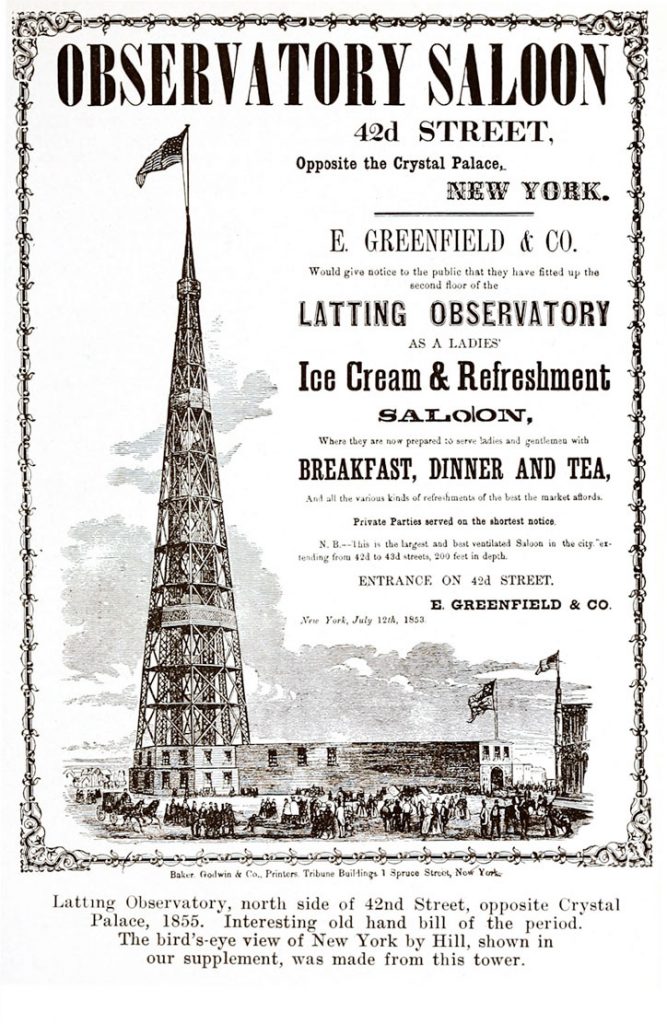

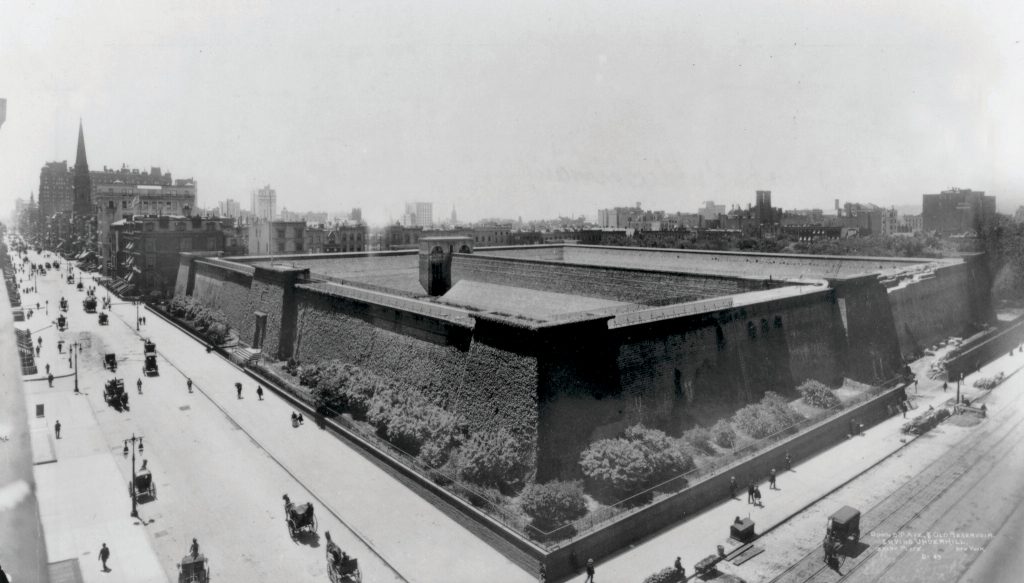

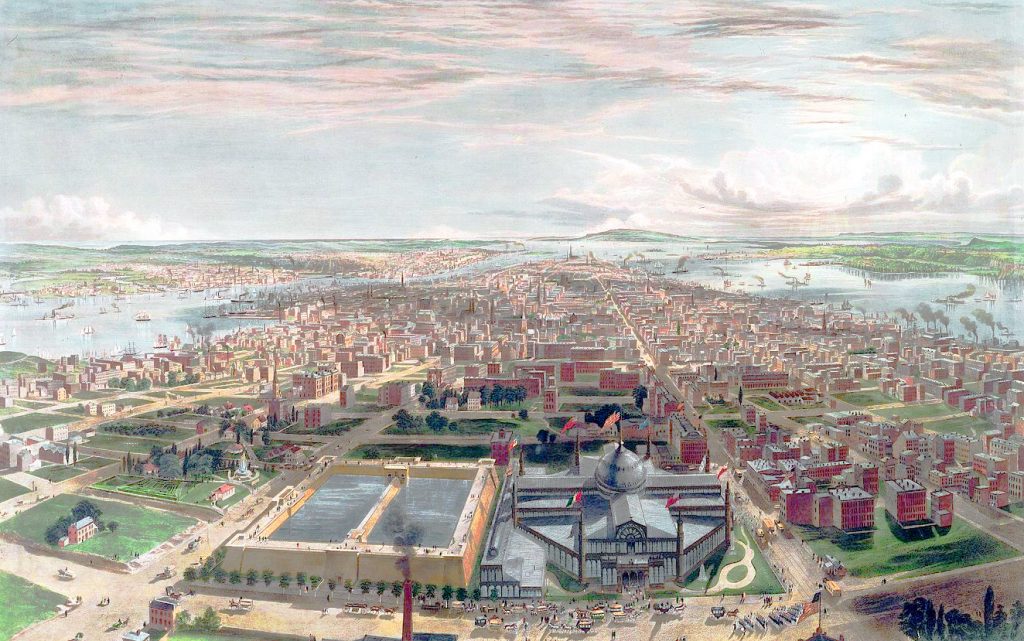

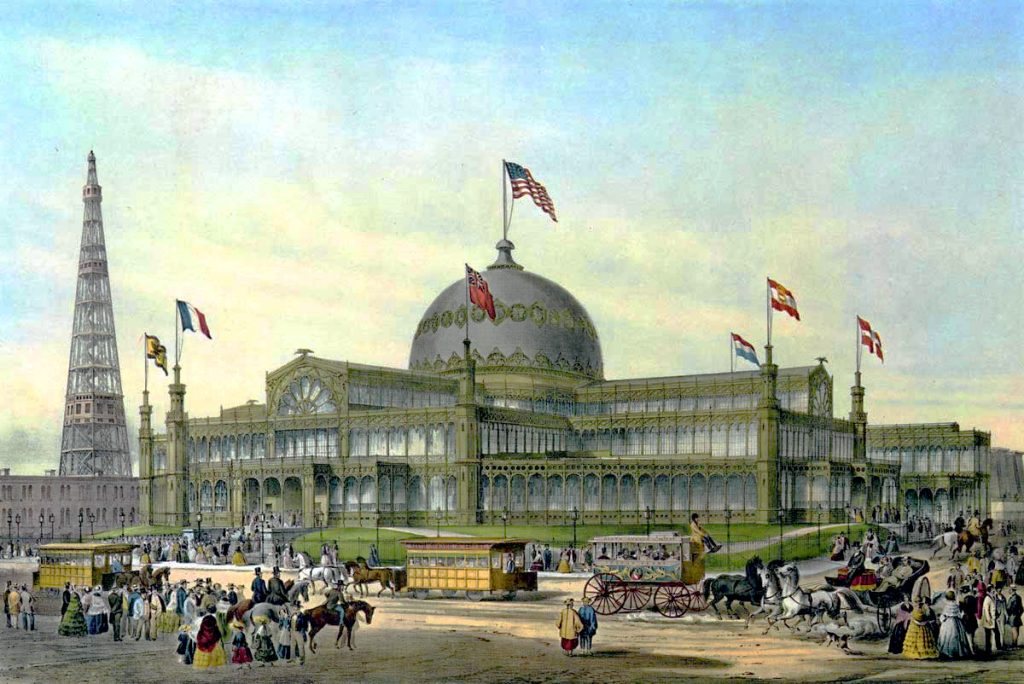

In 1853 a crystal palace was constructed in New York, with their own viewing tower, made in the same way many oil-rigs were.

1853 New York

New York Crystal Palace was an exhibition building constructed for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City in 1853

The New York Exhibition hall was burnt down in a fire.

1855 Paris

Then in 1855 Paris then had their own exhibition where the Palace of Industry was built for the occasion, inspired by the Crystal Palace. France thus shows its ability to renew the technical feat, even adding a stone facade, which fascinates the public.

Construction of the Grand Palais began in 1897 following the demolition of the Palais de l’Industrie (Palace of Industry) as part of the preparation works for the Universal Exposition of 1900

1889 Paris

1900 Paris

Crystal Palace, originally constructed in London’s Hyde Park in 1851. Later it was dismantled and rebuilt to a different design on Sydenham Hill in south London. The second Crystal Palace burned down in 1936 but the local district still bears its name.

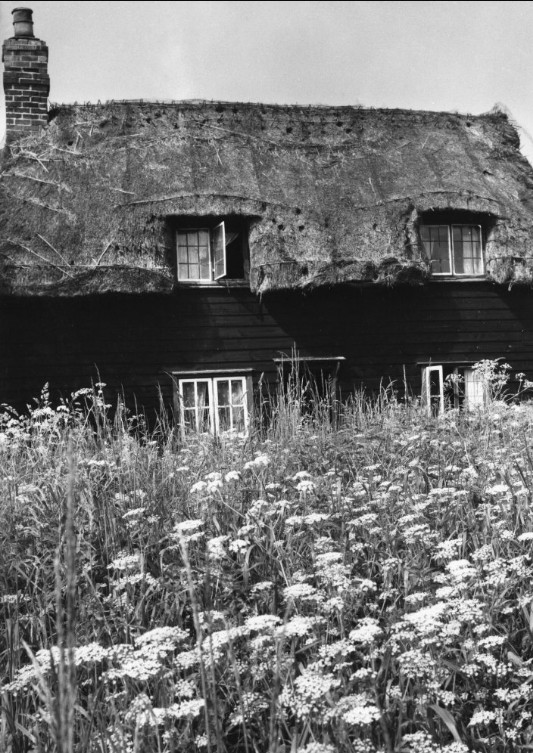

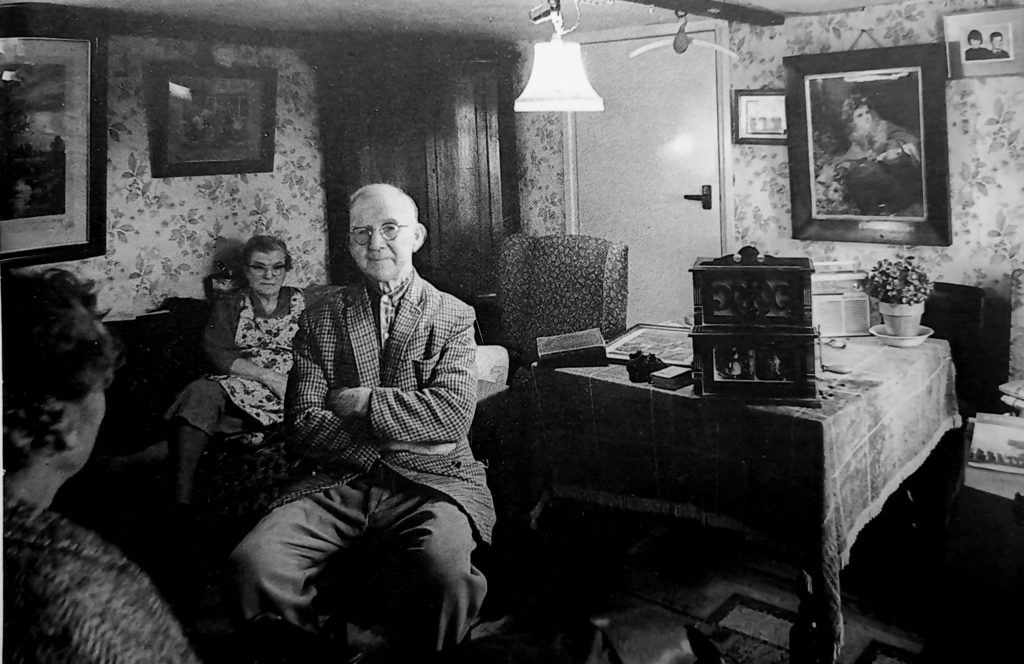

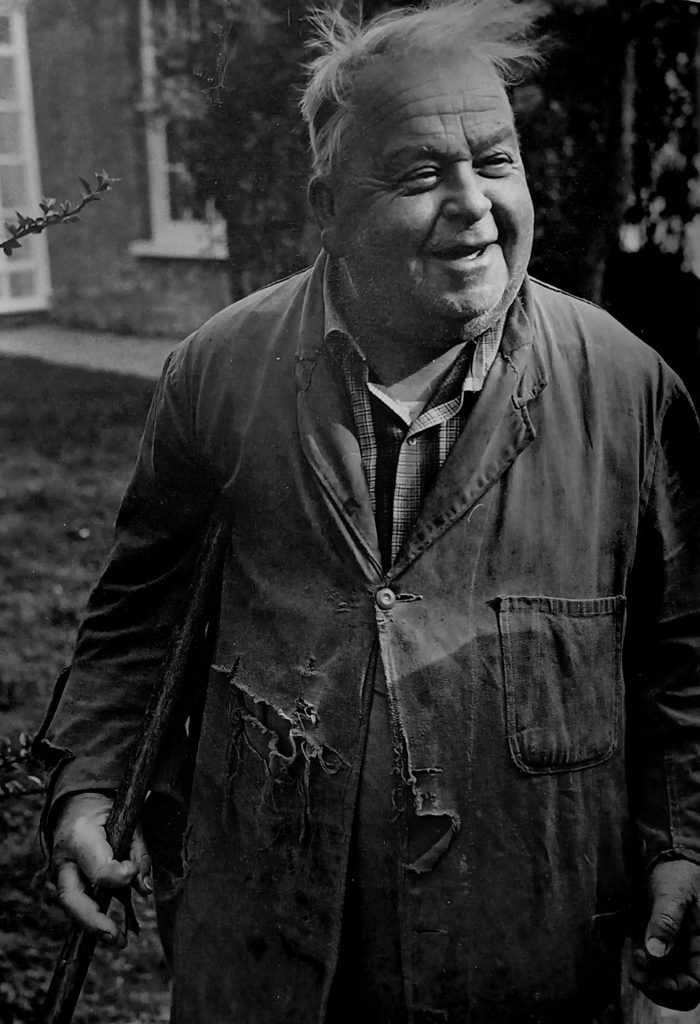

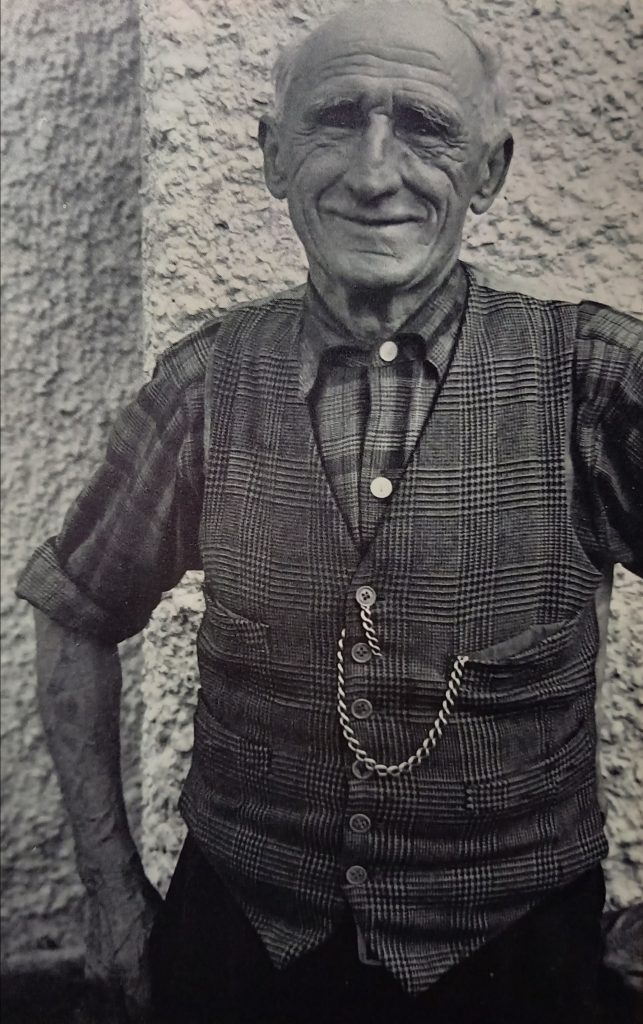

In this blog post photos are more than just something pretty, but political. If a picture says a thousand words then these photographs of Anstey, Hertfordshire by Edwin Smith are designed to show you unspoilt beauty. The aim is to try to stop an airport being built. Both Edwin Smith and his wife, Olive Cook, had opposed the building of Stansted airport near their home of Saffron Walden and lost, this became Cook’s book, The Stansted Affair, A Case for the People (1968). Two years later their focus was Anstey.

With conservation such a topic of the modern world, and with another runway at Gatwick always threatened now, this pairing were countryside conservationists through art. This isn’t a new thing, Clouth Ellis had started an interest of landscape conservation in 1930 with his book The Face of the Land and even Beatrix Potter was doing a similar thing by buying the farms around her home to save them from property developers. David Gentleman produced his lithograph series of Covent Garden with the idea of helping to both protect and record it from mass redevelopment.

The following pages were written at the request of the Nuthampstead Preservation Association. Because the matter was urgent I had to confine myself to the investigation of a single parish and Anstey was chosen because its topographical, architectural and sociological features seemed to typify those of the whole district which would be disrupted by the siting of a Third London Airport at Nuthampstead. Ideally it would have been more rewarding to make a detailed study of the entire territory, which has proved to be extraordinarily rich and interesting and on which little work has so far been done. Such a study would have thrown a clearer light on the movements of the population over the centuries and on the connections between long established families all over the area. The sketch of the countryside with which this essay begins does no more than scratch the surface of the subject, but it has been included to give perspective to what I have been able to discover about Anstey during the last two weeks.

Olive Cook – Anstey, 1970.

The church of Saint George is a cruciform building of flint with stone dressings. The earliest parts are the chancel, transepts and crossing tower, all of which were built in the 12th century. The church was altered in the 13th century and the nave was rebuilt in the 14th century. The South porch and the top stage of the tower are 15th century. The church was restored in 1871–72 under the direction of the Gothic Revival architect William Butterfield. Repairs in 1907 were directed by the architect Arthur Blomfield.

Two bonus pictures from the RIBA that were not included in the book.

If you are local to the Great Bardfield area you might have noticed the government plans to build a mega prison in Weathersfield. If you have not please click here.

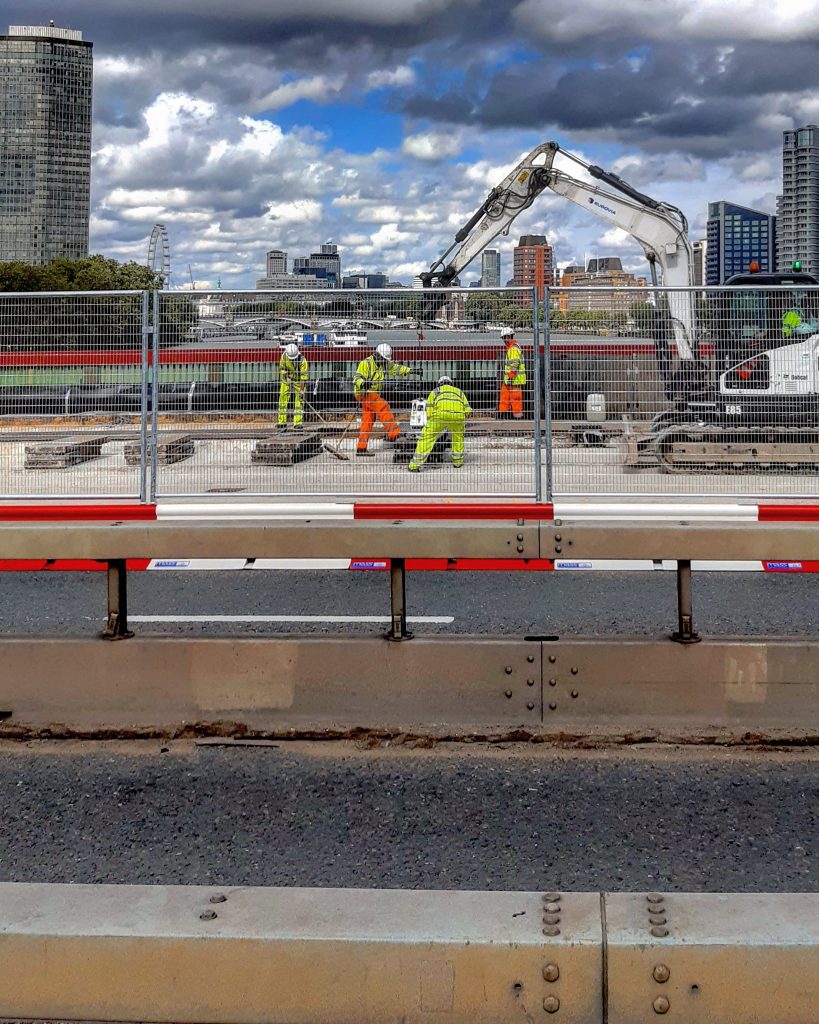

This is just a camera reel of my last year in London. Some of the pictures are early and others are the Summer. I think it is important to memorialise those times even though it looks like it will be around a lot longer than we hoped.

The barriers here, according to the staff were the surplus for crowd control to place people queuing for the British Museum.

Part of the Thankyou NHS craze where people showed support for the workers of the health service. This was the first time I had seen it on a bus. I do like the idea of children making the signs too that hung in so many houses.

The empty restaurants just before the Lockdown

Below is the urinal in Tate Britain. Part of the social distancing measures to keep people two metres apart.