Today it is hard to ignore the artist effect of Eric Ravilious, the tide of books on him alone prove his popularity. This is an article from ‘The Artist’ magazine, March, 1943. It ends with a short record of his death, some weeks before. I thought it was interesting that its intention was a review of his life and works but became an obituary.

Eric Ravilious by Richard Seddon

Artists of note: Number 97. The Artist Magazine. March 1943

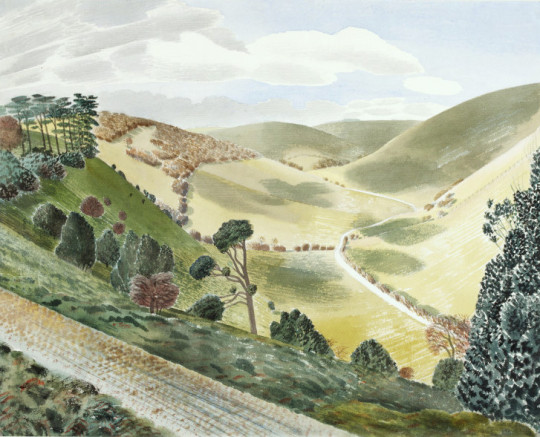

Eric Ravilious – The Causeway, Wiltshire Downs, 1937

Paul Nash was the first to notice the work of Eric Ravilious. This happened when Ravilious was a student of the Royal College of art under the instruction of Nash in the school of design. His wood engraving impressed Paul Nash as being worthy of special attention, and it was on the latter’s introduction that Ravilious became a member of the Society of Wood Engravers. In the society’s exhibitions Ravilious’s engravings immediately drew attention from publishers and their agents. Ravilious illustrated several books and was soon established as a book illustrator of exceptional status.

Between that time and the present he has consolidated a reputation as a leader of contemporary art; not as a leader in figurative or influential, but rather in the most academic sense, of the advancement of research and knowledge. He does not supinely follow the present tendencies and work in a certain manner merely because that manner can be accepted as the logical outcome of the particular form of art and aesthetics accepted at the moment in the country. He does not look for what is being done nowadays, in order to do likewise.

Leadership in art, as in anything else, calls for the usual hackneyed attributes: courage, self-confidence, faith in purpose, and so on. But in art, somehow, as in anything abstract, it needs enthusiasm enough to keep it up in the face of that inexplicable hostility that people show in face of anything that is ‘new.’

In feeling and temperament the work of Ravilious is very English. Ravilious, unlike so many Englishmen, does not try to paint as though he were a Frenchman. His work has its roots deeply sunk into the life and the countryside and the culture of England. His water colours are the lineal descendants of the English eighteenth century school of water colour than in its time gave England a brief reign as a country important in the world’s art, a reign that lasted until the French impressionists wrested the sceptre for France, a reign into which, it is felt, England was re-entering at the beginning of this war, through the excellence of the contemporary school of English landscape, of which Ravilious is one of the most important members.

That, because of his very full knowledge of the history and methods of English art and design, he carries on the English tradition, is apparent in his work in any of the media he employs. His wood engravings revive and extend the essential tradition of Thomas Bewick and the English eighteenth century wood engravers. In his water colours he takes up the story where Peter de Wint, Paul Sandy, John White Abbott and their contemporaries left off, and carries it a stage farther, in the life of modern knowledge. Examples of his pottery design that he carried out for Wedgwood can take their place in the Victoria & Albert Museum, among the original products of Josiah as if by hereditary right.

It is not possible to select one or two influences that can be credited with the moulding of Ravilious’s vision. After leaving school in Eastbourne, he attended Eastbourne School of Art, from where he went up to the Royal College of Art, in London. There, under principal-ship of Sir William Rothenstein, he was tutored by some of the most important contemporary artists in the country. Naturally, the powerful influences of such men must have affected his outlook; indeed, they did. In addition he received, asI have said, an exhaustively comprehensive education in art and design, from which soure he derived the solution of those problems of expression that he always seems to face with courage and solve with ingenuity.

He might easily have been tossed for ears upon a sea of conflicting influences; if so, it happened when he was at the R.C.A., and the process was completed by the time he began his career as a practising artist. At least, no indecision has ever shown itself in the work of his maturity. that he owes something, as all artists, to skilful pilotage, can be safely assumed, but that he emerged with an original style is patently a logical result of his own personal outlook.

Eric Ravilious – Design for Coronation mug for Edward VIII, 1936.

He is thirty eight, and therefore can be said to have not yet reached the peak of his artistic maturity. As regards his work, whatever the medium he invariable approaches a subject with an open mind and embodies in the work, whether it is a wood engraving, a water colour, ceramics, or fabric design, at least one idea that arises from the needs of that particular job and no other. Of course he refers in his mind as he is thinking it out not only to history but to past works of his own to help in solving the problem of the moment, but he avoids any tendency to repeat successes of the past ad nauseam, giving the same colours, the same subtleties, the same textures and so on, whether or not they are the right ones for the present job. I stress the fact that he does not walk in such a manner because very many artists, both distinguished and otherwise, do so.

Ravilious never rests on his laurels. It cannot be said about a sequence of his work as it can of the work of other artists that, having seen one, you have seen them all. Though they are all built around the personality of the artist, each of his productions is sufficient unto itself.

Eric Ravilious – Rendering Mines Safe, 1940. (Now called Dangerous Work at Low Tide)

In a Ravilious exhibition, the paintings are, in the truest sense, variations on a theme and not repetitions. It is said that there are four different ways of looking at a picture, Firstly the observer might stand away and savour the emotional content and the subject matter.Secondly, he might appreciate the purely academic appeal, such as the colour harmony and the broad lines of the composition. Thirdly he might go near the picture and closely examine the technical minutiae: the brushwork, the qualities of the surface, the interplay of ‘fat’ and ‘lean’ painting, and so on. Fourthly, he might scrutinise, analytically, the patterns achieved by the painter, by the use of his range of different ways of coving a surface and of filling in a space.

The Victorian painters appealed to the first two methods, and many contemporary schools solely to the last two. A few contemporary painters, including Eric Ravilious, appeal to all four. Ravilious particularly appeals to the last. His textures and patterns, whatever the medium, are an important feature of his work. He composes as a rule within a tight linear framework, making spaces of carefully contrasted size and shape which he fills with textures that derive partly from the intrinsic textures of the original of the subject and largely from his own fertile imagination. The settings for his landscape painting have been the Downs and coast of Sussex, and localities in Essex, Wiltshire and Wales.

Apart from his war painting he confesses to a tendency to paint in sequences: groups of broken-down tractors and old cars and buses in fields, the discarded machinery of Essex. He has painted a series of Sussex hills, a set of chalk figures (such as the Aylesbury White Horse), a set of lighthouses, rowing boats, beds, beaches and greenhouses. Ravilious was educated at Eastbourne Grammar School. He left the Royal College of Art only to return in 1929 as instructor in design, which position he filled until 1938. Whilst a student at the college he and Edward Bawden completed a well known mural decoration in the refreshment room of Morley College, which was destroyed by a bomb.

Other important mural decorations by Ravilious are those in the circular room at the L.M.S. Hotel at Morecambe and the ceiling decorations in the dining hall of the new Merchant Taylors’ School. Since 1926 he has illustrated books for the Kynoch Press, mainly by wood engravings. His engravings have also illustrated Volume I of ‘Signature’ and Gilbert White’s ‘Selborne.’ From 1937 to 1939 he designed pottery for Wedgwood. One of the best known of these designs was the Coronation Mug. His designing for glass he dismisses as a mere gesture; as a gesture it was brief, but effective.

Exhibitions of the work of Ravilious were held at the Zwemmer Gallery in 1934 and 1937, and one at Tooth’s in 1939. Three of his water colour drawings are in the Victoria & Albert Museum, and there are others in the public galleries. At the beginning of the present war he was offered and he accepted an appointment as official war artist to the Admiralty. He holds with the rank of hon. captain in the Royal Marines.

Eric Ravilious – Lewis Gunner

Since this article was written, Eric Ravilious has been posted as ‘missing’. After spending a period in Iceland, in his capacity as official war artist, he life that island by plane and has not been heard of since. Thus ends the career of a very fine artist, whose last efforts were devoted to recording events connected with the war – records which will go down to posterity, and which will keep his memory green, especially in the art world which respected him for his achievements. He was a sane progressive, sound in judgement and method.

Eric Ravilious – Convoy From Merchant Ship At Anchor, 1943