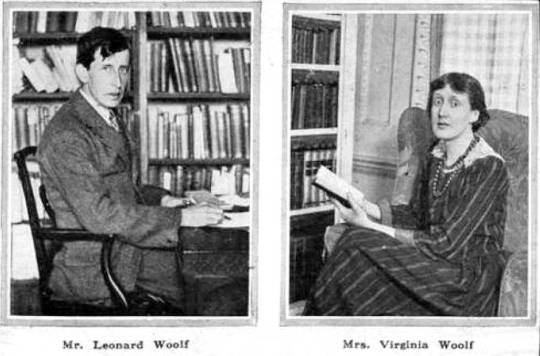

Leonard and Virginia Woolf had retreated from London to their country home, Monk’s House, Rodmell. Virginia Woolf’s apartments at 52 Tavistock Square and 37 Mecklenburgh Square were both blitz damaged and the countryside was more peaceful for both to work in. Rodmell, like Charleston are both located south-east of Lewes.

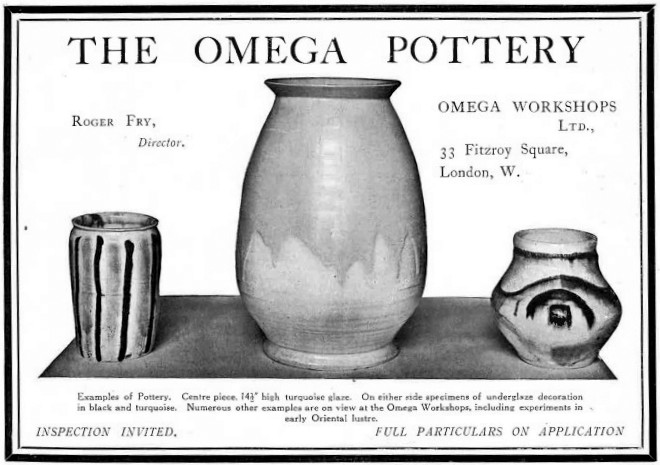

In 1940 Virginia had published a biography on her late friend Roger Fry and in the wartime conditions the, reviews were not abundant and although she had finished the manuscript for her last (posthumously published) novel, Between the Acts she fell into depression and was unable to write.

Virginia had chosen to take her life and on that day was missing from Monks House, she had left a letter for him. After looking all over the house and garden Leonard was sure she would have gone to the river:

“I ran across the fields down to the river and almost immediately found her walking-stick lying upon the bank. I searched for some time and then went back to the house and informed the police.

On 28 March 1941, Woolf drowned herself by filling her overcoat pockets with stones and walking into the River Ouse near her home.

Woolf’s body was not found until 18 April. Her husband buried her cremated remains beneath an elm tree in the garden of Monk’s House, their home in Rodmell, Sussex.

On the day of her death Leonard wrote:

I found the following letter on the writing block in her work-room. At about eleven on the morning of March 28 I had gone to see her in her writing-room and found her writing on the block. She came into the house with me, leaving the writing-block in her room. She must, I think, have written the letter which she left for me on the mantelpiece (and a letter to Vanessa) in the house immediately afterwards.

Virginia Woolf’s Suicide Note to Leonard:

Dearest,

I feel certain that I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier ‘til this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that — everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer.I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been. V.

Virginia Woolf’s Letter to her sister, Vanessa Bell:

Dearest,

You can’t think how I loved your letter. But I feel that I have gone too far this time to come back again. I am certain now that I am going mad again. It is just as it was the first time, I am always hearing voices, and I know I shan’t get over it now. All I want to say is that Leonard has been so astonishingly good, every day, always; I can’t imagine that anyone could have done more for me than he has. We have been perfectly happy until the last few weeks, when this horror began. Will you assure him of this? I feel he has so much to do that he will go on, better without me, and you will help him.

I can hardly think clearly any more. If I could I would tell you that you and the children have meant to me. I think you know.I have fought against it, but I can’t any longer. – Virginia.

Front cover of the New York Times, 3rd April 1941.

The news that Virginia was missing was posted in the papers, and although her body was not washed up for two and a half weeks it was presumed she was lost, feared dead.

Below the two quotes are from the diaries of Frances Partridge, wife of Ralph. Although she seems unaffected, it was maybe from being on the outer orbit of the Bloomsbury group.

April 3rd

Opening The Times this morning I read with astonishment: “We regret to announce that the death of Mrs. Virginia Woolf, missing since last Friday, must now be presumed.” From the discreet notice that followed it seems that she is presumed to have drowned herself in the river near Rodmell. An attack of her recurring madness I suppose; the thought of self-destruction is terrible, dramatic and pathetic, and yet (because it is the product of the human will) has an Aristotelian inevitability about it, making it very different from all the other sudden deaths we have to contemplate.

April 8th

Sat out on the verandah, trying to write to Clive in answer to his letter about Virginia’s death. He says: “For some days, of course, we hoped against hope that she had wandered crazily away and might be discovered in a barn or a village shop. But by now all hope is abandoned … It became evident some weeks ago that she was in for another of those long agonizing breakdowns of which she has had several already. The prospect two years insanity, then to wake up to the sort of world which two years of war will have made, was such that I can’t feel sure that she was unwise. Leonard, as you may suppose, is very calm and sensible. Vanessa is, apparently at least, less affected than Duncan, Quentin and I had looked for and feared. I dreaded some such physical collapse as befell her after Julian was killed. For the rest of us the loss is appalling, but like all unhappiness that comes of ‘missing’, I suspect we shall realize it only bit by bit.”

After the funeral of Virgina, Leonard buried her ashes at the foot of the great elm tree in their garden. There were two great elms there with boughs interlaced which they always called Leonard and Virginia. In the first week of January 1943, in a great gale one of the elms was blown down.

Leonard Woolf – The Journey not the Arrival Matters, Hogarth Press, 1969.

Frances Partridge – A Pacifist’s War, Hogarth Press, 1978

New York Times, 3rd April 1941.