In The Listener, April, 1941, there is a tribute by Stephen Spender on the death of Virginia Woolf. Below is the full text.

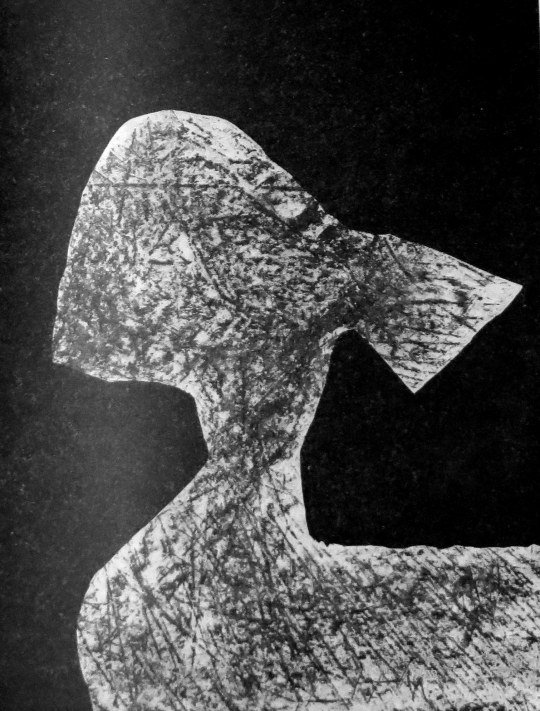

Vanessa Bell’s Portrait of Virginia Woolf

In these dark times, the death of Virginia Woolf cannot strike her circle of friends and admirers except as a light which has gone out. Whatever its significance, her loss is irreparable. Her strength-and perhaps also her weakness lay in her rare mind and personality. Moreover, the quality of what she created had the undiluted purity of one of those essentially uncorrupted natures which seem set aside from the world for a special task by the strangest conjunction of fortune and misfortune.

Yet when one thinks of what Virginia Woolf achieved, her life appears far more a wonderful triumph over many difficulties than in any sense a defeat. In a different time or in different circumstances, she might well have died far younger and with far less finished. As it is, although she died at the height of her powers, she had completed the work of a lifetime. The history of other writers who have suffered from ill-health shows how much there is here to be grateful for.

Her best novels, or prose poems in the form of fiction, are The Voyage Out, Jacob’s Room, Mrs. Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, Orlando, The Waves. Although all of these novels have tn common the qualities which distinguish her writing, they differ not merely in portraying different material, but in having different artistic aims. Indeed the artistic aims in Virginia Woolf‘s novels are far more varied than the material, which is somewhat narrow and limited.

Most novelists having achieved, by about their third novel, a mature style, continue to write novels in that style, but covering different aspects of experience. With Virginia Woolf, however, style, form and material are indivisible. With every new novel she was ‘trying to do something different’, especially with time. For example, the whole action of Mrs. Dalloway takes place in one day: the first long section of To the Lighthouse describes a scene lasting for perhaps an afternoon ; this is followed by a very short section describing the passage of several years, illustrated by the decay of an empty house. Orlando is a fantastic account of someone who lives for several hundred years. beginning as a man and turning into a woman. The Waves is a poetic account of people seen through each other’s minds through all their lives, speaking their thoughts in poetic imagery to each other. A new way of writing a book was simply a new way of looking at life for Virginia Woolf : she held life like a crystal which she turned over in her hands and looked at from another angle. But a crystal is too static an image; for, of course, she knew that the crystal flowed.

It is a well known device of composers to take a theme and write variations on it. The same tune which is trivial in one light passage in a major key is profound in a minor key scored differently; at times the original tune seems lost while the harmonies explore transcendent depths far beyond the character of the original theme; now the tune runs fleetingly past us; now it is held back so that time itself seems slowed down or stretched out. This musical quality is the essence of Virginia Woolf ’s writing. The characters she creates – Mrs. Dalloway, Mrs. Ramsay, Mr. Ramsay are well defined to be sure, but they are only the theme through which she explores quite other harmonics of time, death, poetry and a love which is more mysterious and less sensual than ordinary human love.

A passage from To the Lighthouse will illustrate the ’ beauty which she could achieve Mr. Ramsay, who is a philosopher – almost a great Victorian – faces the sense of his own an failure: and what are two thousand years? (asked Mr. Ramsay ironically staring at the hedge). What, indeed, if you look from a mountain top down the long wastes of the ages? The very stone one kicks with one’s boot will outlast Shakespeare. His own little light would shine, not very brightly, for a year or two, and would then be merged in some bigger light, and that in a bigger still. (He looked into the darkness, into the intricacy of the twigs.) Who then could blame the leader of that forlorn party which after all has climbed high enough to see the waste of the years and the perishing of stars, if before death stiffens his limbs beyond the power of movement he does a little consciously raise his numbed fingers to his brow, and square his shoulders, so that when the search party comes they will find him dead at his post, the line figure of a soldier. Mr. Ramsay squared his shoulders and stood very upright by the urn. This passage has all Virginia Woolf ’s virtues, and perhaps some of her defects. It starts off by being very faithful even in its irony to the thoughts of Mr. Ramsay. She takes one of those plunges beyond the present situation of her character into the past and the future which strikes one often in her writing as a night of pure poetic genius. But then the focus shifts and the writer has forgotten her character’s thoughts, or perhaps she is regarding him from the outside. But the image of the leader of the expedition in the snow is a little too general, and one begins to wonder whether she hasn’t strayed too far from the particular.

As with the impressionist painters, there are opposing tendencies in her novels. The one is centrifugal, the tendency for everything to dissolve into diffused light and in the brilliant detachment with which their surroundings flow through her characters’ minds. The other is centripetal-the tremendous preoccupation with form which nevertheless holds her novels together and makes them far more significant than if they were just the expression of a new way of looking at life. This doubtless reflects an acute nervous tension in her own mind between a two great sensitivity which tended to disintegrate into uncoordinated impressions, and a noble and sane determination not to lose hold of the central thread.

To have known Virginia Woolf is a great privilege, because it is to have known an extraordinary and poetic and beautiful human being. Some critics describe her as forbidding and austere. Her austerity was not that of a closed-in or a prudish mind. As with all genuinely intelligent people, one could discuss anything with her with the greatest frankness; she was far too interested in life to make narrow moral judgements. Perhaps she was a little too impatient towards stupidity and tactlessness; it is a gift to writers to suffer fools gladly. To be with her was a joy, because her delight and her awareness of everything around her communicated themselves easily and immediately to her friends. What was written on her beautiful unforgettable face was not severity at all, though there was some melancholy; but most of all there was the devotion and discipline which go with the task of poetic genius, together with the price in the way of nervous strain and physical weakness which doubtless she had to pay.