In a garage sale I bought a book of magazines. I love old newspapers and annuals bound into books, it saves them from damage and keeps them in order of date. On that day, I came away with a bound book of The Masses Magazine – A left wing american publication from 1911-1917. It was an interesting period for America, with the Mexican revolution and the start of the First World War happening around them.

“Perhaps the most vibrant and innovative magazine of its day, The Masses was founded in 1911 as an illustrated socialist monthly, and it was soon sponsoring a heady blend of radical politics and modernist aesthetics that earned it the popular sobriquet “the most dangerous magazine in America.”

The magazine had three editors during its first two years—Thomas Seltzer, Horatio Winslow, and Piet Vlag (the magazine’s founder)—but for the remainder of its short life The Masses was brilliantly edited by Max Eastman, who—with Floyd Dell, as managing editor—helped turn it into the flagship journal of Greenwich Village, the burgeoning bohemian art community in New York”. †

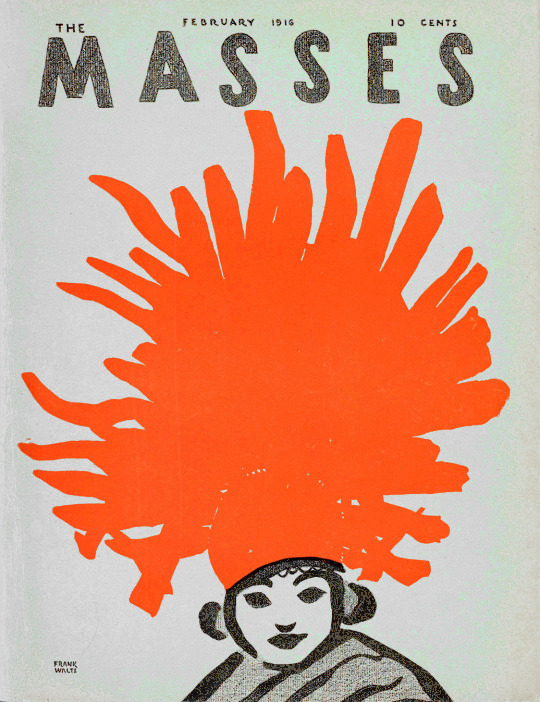

After Max Eastman took over editing the magazine, the front covers became more colourful and less conservative looking. Inside the magazine the lithographs and illustrations became more contemporary, looser drawings rather than cartoonish ‘Punch’ like illustrations.

In his first editorial, Eastman argued: “This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers.”

The Masses magazine cover, by Frank Walts, 1916.

Many scholars have noted the high quality of the writing, imagery and design of the Masses. Specifically, they all identify the magazine’s visuals as its hallmark. The complete list of works that mention the magazine would be too extensive to list exhaustively, but in a number of works, the Masses takes centre stage. Discussions on the magazine and imagery can be found within histories of print journalism and the little magazine; works on the intellectual and artistic life of New York City in this period. ‡

Max Eastman was accused later on of going against the collective nature of the magazine when he wrote and published articles and illustrations without consulting the board who hired him. Eastman hired an assistant editor, Floyd Dell, he recalled “some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures”.

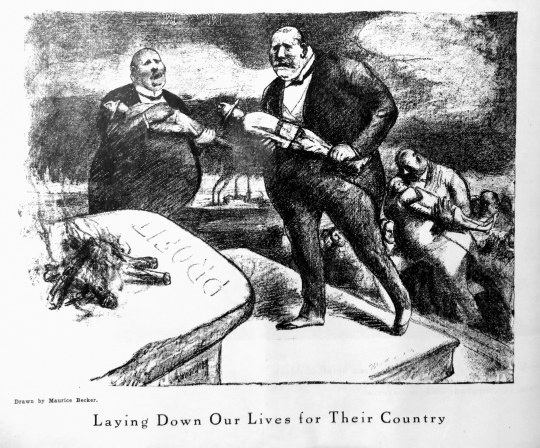

Maurice Becker – Laying Down Our Lives for Their Country

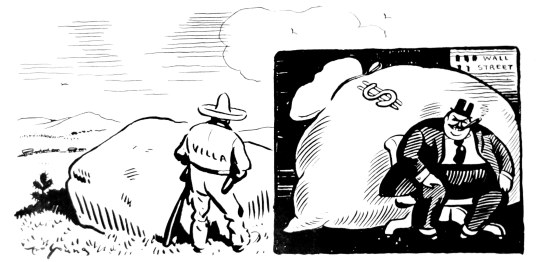

Above is a typical illustration from the magazine; Capitalists laying down the bodies of soldiers at the alter of Profit. The magazines socialist agenda wasn’t masked at all. Below a picture about the Mexican Revolution and how a Mexican is hiding behind a rock from gunfire where as the American Fat Cat is hiding behind the gold of Wall Street.

Maurice Becker again, – This was one of the more interesting illustrations, it was untitled – drawn direct onto newspaper print and then printed up. Maybe unknowingly initiative.

Maurice Becker – Christmas Cheer, 1914.

The picture above is captioned “Cheer up, Bill – time next Christmas comes around, we may be prisoners of war.”

In 1918 Maurice Becker became a conscientious objector to American participation in World War I. He fled to Mexico with his wife to avoid the draft. He was arrested upon his return to the United States in 1919 and was tried, convicted, and sentenced to 25 years of hard labour, of which he served 4 months at Fort Leavenworth prior to commutation of his sentence. After he was released he lived in Mexico for a few years before returning to America.

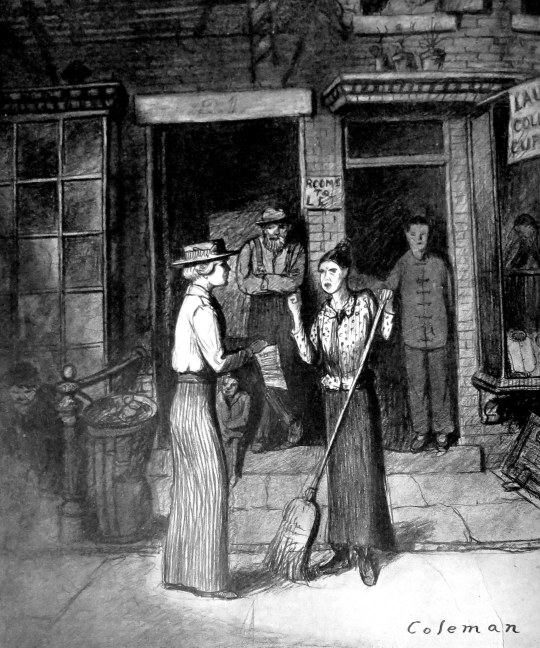

Glenn O. Coleman – Overheard on Hester Street.

(To the Suffrage Canvasser) “You’ll have to ask the head of the house – I only do the work.”

The Masses, as in the picture above, were keen to promote women’s rights.

The magazine vigorously argued for birth control (supporting activists like Margaret Sanger) and women’s suffrage. Several of its Greenwich Village contributors, like Reed and Dell, practised free love in their spare time and promoted it (sometimes in veiled terms) in their pieces. Support for these social reforms was sometimes controversial within Marxist circles at the time; some argued that they were distractions from a more proper political goal, class revolution.

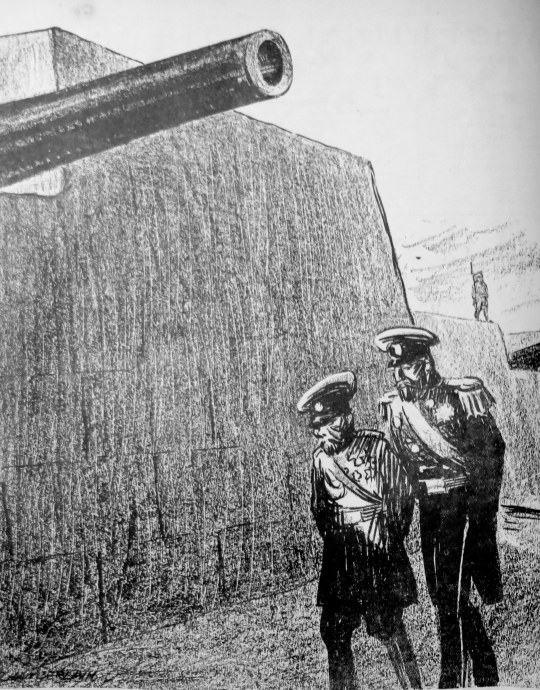

K. R. Cahmberlain – At Petrograd

Russian Officer: ‘Why these fortifications, your Majesty? Surely the Germans will not get this far!” The Czar: “But when our own army returns…?”

It’s hard to say if the Masses did anything at the time to change the political thinking of America. It’s true to say they sponsored and promoted art and writers that would go on to become significant. As a historical document, it’s value has been justified by time.

The Masses found itself constantly entangled in lawsuits claiming libel brought by major corporation and syndicates (most notably the Associated Press), and eventually the government, invoking the Espionage Act of 1917, barred it from the mails in August 1917 for its critique of the U.S.’s involvement in World War One. Without being able to ship the magazine to it’s subscribers the magazine folded.

† http://modjourn.org/render.php?view=mjp_object&id=MassesCollection

‡ Constructive images: Gender in the political cartoons of the “Masses” (1911–1917)