Michael Rothenstein was born in 1908 in Hampstead, London and the youngest of four children of Sir William Rothenstein and Alice Knewstub. His brother John became a director for the Tate Gallery and had connections with the Bloomsbury Set.

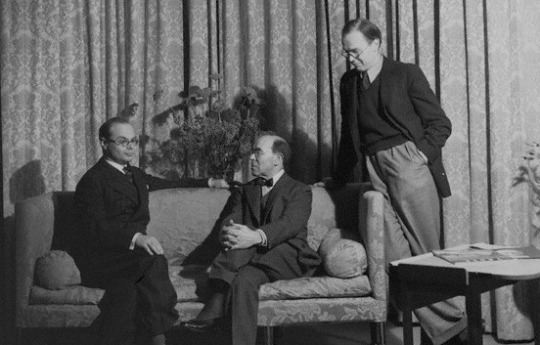

Howard Coster’s photo of John Rothenstein; Sir William Rothenstein; Michael Rothenstein (standing), National Portrait Gallery, 1939.

Michael was homeschooled and studied art at Chelsea Polytechnic

and later at the Central School of Arts and Crafts (1924-27). His mother was American and his father British, the family home was also a social and happy one.

If we accept the frequent probability of children’s rebelling against the lives and pursuits of their parents – or at least their parental environment – Michael Rothenstein’s early years might well have destroyed any burgeoning of a creative disposition. But as a child and as a young man, he actively enjoyed the not affluent but very comfortable style of an artist’s household in which Augustus John, Wyndham Lewis, Edward Burra, Stanley Spencer, David Jones, Edwin Lutyens or the young Henry Moore were received and he often rubbed shoulders at supper or tea parties with Walter de la Mare, Barnett Freedman or Robert Graves.†

Affected by lingering depression due to myxoedema, he did little art making during the late 1920s and early 1930s. Despite this, he had

his first one-man show at the Warren Gallery, London in 1931.

Michael Rothenstein – Three Women by the Sea, Jerwood Gallery, 1938.

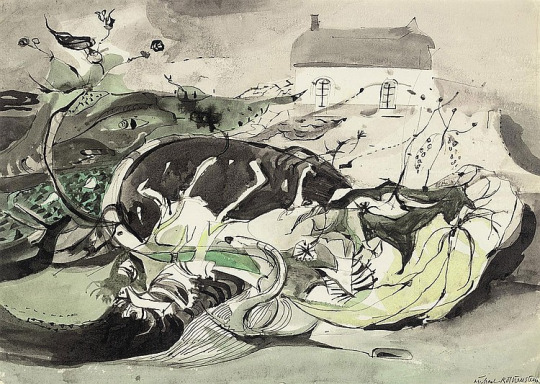

His work and style of the late 30s and early 40s was part of the neo-romantic water-colourist set that artists like Thomas Hennell, Claude Muncaster, Eric Ravilious and Paul Nash had been championing for a decade. These watercolours are best showcased by the work he created for the Recording Britain project.

Michael Rothenstein – Kilburn Church from the South, V&A, 1940. (Recording Britain)

In 1941 Rothenstein moved to Great Bardfield, staying first at ‘Place House’, where John Aldridge also lived, before moving to ‘Ethel House’. As his style progressed away from the Recording Britain project he could be more abstract and free with his artworks, moving to Great Bardfield gave him a community of artists and a resource of subjects to work with. He started a long association with the Redfern Gallery, with his first show in 1942.

Michael Rothenstein – Autumn, 1947.

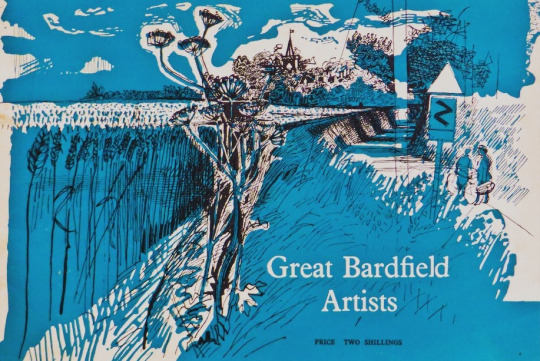

The community of Great Bardfield in the 1940s had Rothenstein in contact with artists like John Aldridge, Edward Bawden and Kenneth Rowntree. Bawden moved to the village in 1925 and Rowntree in 1939. Following Rothenstein over the next decade would be George Chapman, Stanley Clifford-Smith, Audrey Cruddas and textile artist Marianne Straub. The village would go on to hold events and make it one of the artistic centres for East Anglia alongside Colchester and its School of Art.

Cover of the Great Bardfield Artists 1957-58 Exhibition Catalogue (Design by Walter Hoyle)

During 1945 he submitted a lithograph for the Schools Prints series, ‘Timber Felling’, it was the fifth print of the first series and is one of his most recognisable works. He also illustrated the Sussex volume of Visions of England in 1947.

Michael Rothenstein – Timber Felling, 1945. (Schools Prints SP5)

In 1948 Rothenstein would learn about lithographic printing with the two sisters, Frances Byng-Stamper and Caroline Byng-Lucas whom had set up Millers Press in Lewes, East Sussex. Their express purpose was to revitalise the art of lithography in the French style, art-lithography having become unfashionable in early twentieth century Britain and seen as the tool of a ‘commercial artist’.

Together with new lithographs, over the next few years Rothenstein would print many monotype experiments at his home in Great Bardfield.

Michael Rothenstein – The Cockerel, From my collection, 1950.

In the 1950s he embraced printmaking over painting working in every area of the medium. In 1952 he travelled to Paris to the ‘Atelier 17′ studio to work with Stanley William Hayter – the surrealist print-maker; under his influence it is credited that Rothenstein started his bold experiments in printmaking. The prints he produced were modern and colourful and very chunky mixing woodcuts with screen-prints or etchings. In this form of work he had discovered his true style making the farmyards and fields of Great Bardfield into lively prints.

Michael Rothenstein – Quarry (White Cliff), V&A, 1955.

The first stages of the printmaking revival started with the boom in book sales and publishing from 1900. As publishers looked for more artistic illustrators the medium jumped into the art world with limited edition framed prints becoming more popular into the 1930s. Lithography, lino and the woodcut were the springboard in the 40s and 50s for large scale limited edition images that could be presented as art in multiable copies; with a painting you only have one sale, with a print you have many. Rothenstein, with his ongoing experiments into printmaking, found himself with a younger set of artists pushing the boundaries of printmaking and riding the British wave of Pop Art.

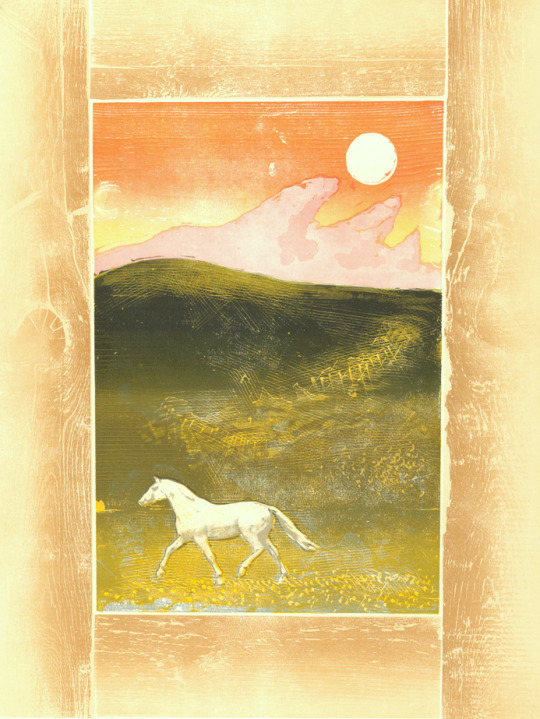

Michael Rothenstein – Horse and Sunrise, From my collection, 1974.

Horse and Sunrise is made with wood timbers bolted together in a frame like metal type is in a letterpress. The centre is made of two more woodblocks of (1) the sky and land, and (2) the green hill top shading. The horse is a screen-print layer

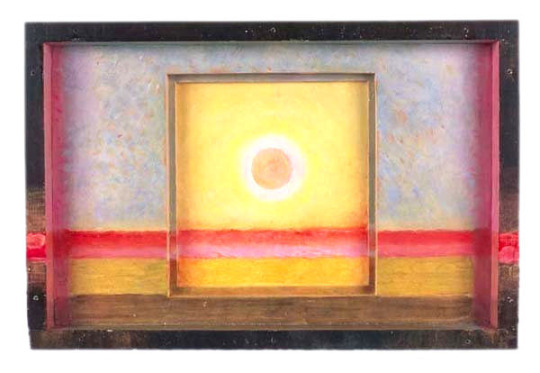

Michael Rothenstein – Sunrise at 36,000 ft, From my collection, 1973

Sunrise at 36,000 ft is a woodcut with multiable pieces of wood bolted together and a colour intaglio print with multi-colour shading, blending and intaglio details. In the 60s Rothenstein started to construct box pieces made from found items. Painted or covered with his prints they blurred the perceptions of painting, sculpture and printmaking.

Michael Rothenstein – Sun Box II, 1975.

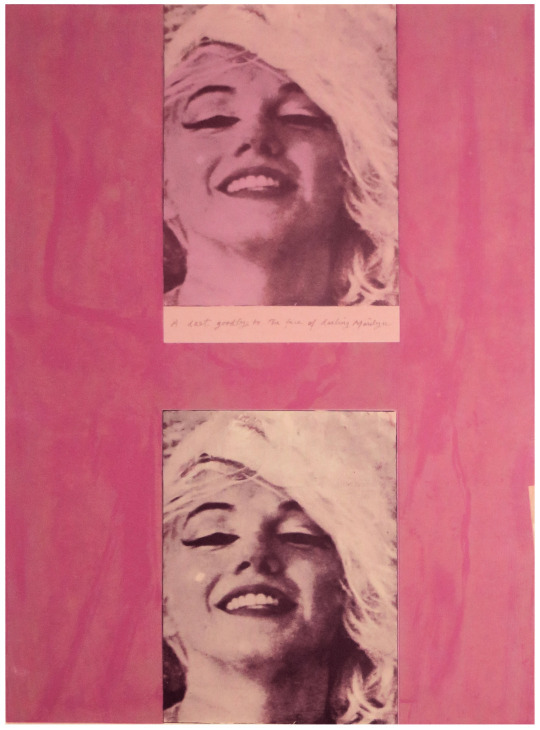

The works that set Rothenstein into becoming a Pop Artist are mostly the ones with screen-print overlays, like in the Marilyn Monroe print.

Michael Rothenstein – Marilyn I, From my collection, 1978

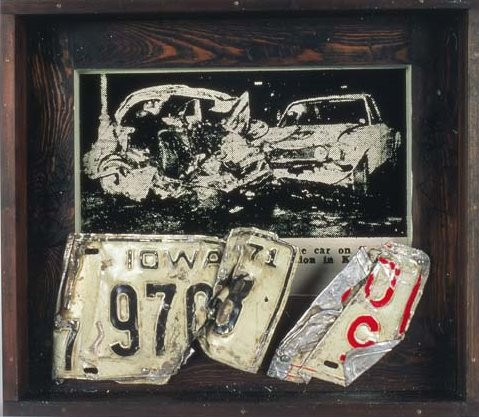

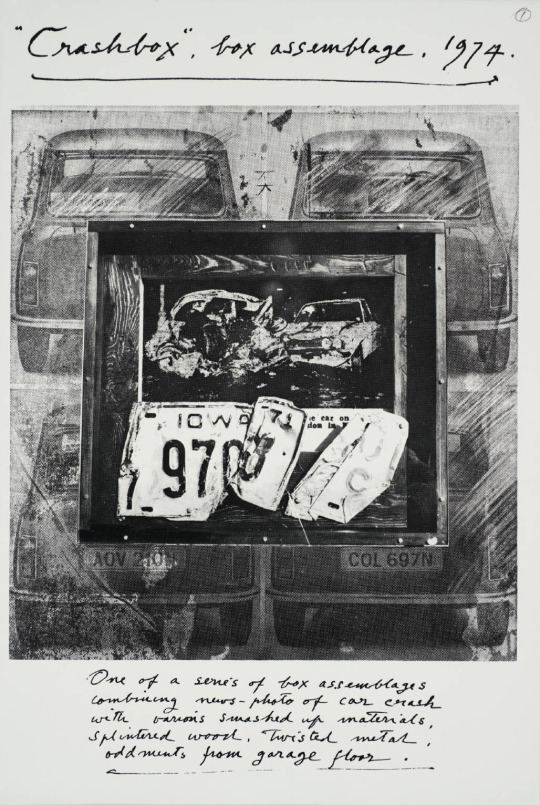

The fundamentals of Pop Art are using ‘found objects’ to make major commercial artworks. Like Warhol and Lichtenstein, he blew-up the size of pictures from newspapers and bolted them with real items in his boxes.

Michael Rothenstein, for instance, has applied boundless energy to extending the range of the relief process of wood and lino, sometimes combining them with screenprint and photo-screen. ‡

Michael Rothenstein – Crash Box I, 1973

Michael Rothenstein, Crash Box Assemblage, Tate, London, 1974

In 1936 he married his first wife, the artist, Betty Fitzgerald, who was later known as Duffy Ayers, and the couple had two children. In 1956 he divorced Duffy and in 1958 married Diana Arnold-Forster. Not long after the 1958 Great Bardfield summer exhibition the couple moved to the nearby village of Stisted, Essex.

Rothenstein was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1977 and a Royal Academician (RA) in 1984. His works are held in international collections.

Michael Rothenstein – Black Mast, Dalmatian Sea, From my collection, 1958.

† Obituary: Michael Rothenstein by Bryan Robertson, The Independent, 1993

‡ Printmaking in Britain by Richard T. Godfrey, 0714818380, 1978.