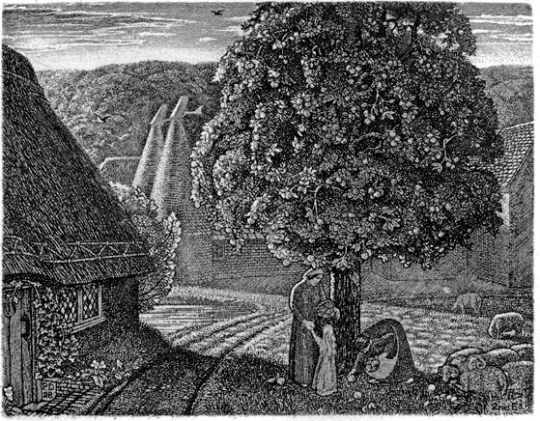

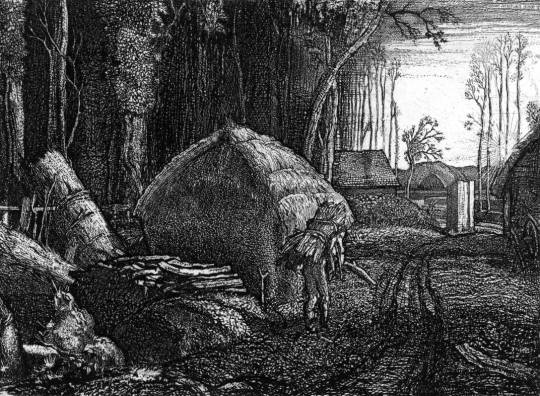

Graham Sutherland – Number Fourty-Nine, 1924

Rather like my post on Graham Clarke, where I complained of his etchings and promoted his linocuts, in this post I would sooner promote and have a Sutherland etching than any of his other works.

I don’t know why I dislike so many of his paintings and to my opinion he only got worse with time. His work before WW2 seemed to have the sinister lust for mocking everything into destruction. It is almost as if he was calling for the war and then to use it as source material afterwards.

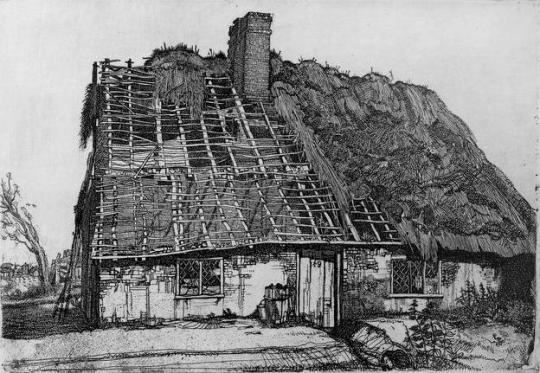

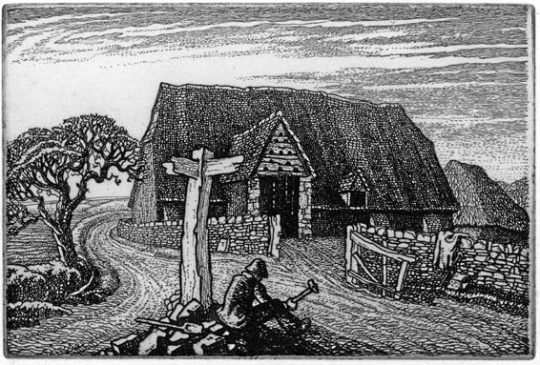

Frederick Landseer Griggs – Southwell Minster, 1916

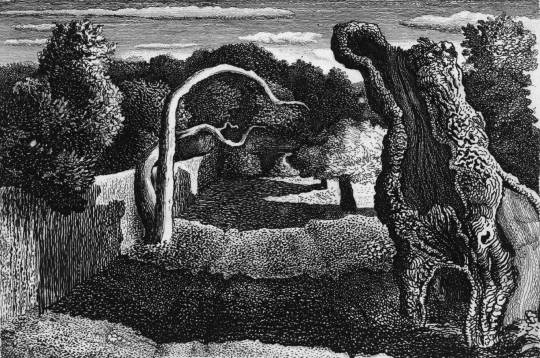

Sutherland was apprenticed as an engineer before studying engraving at Goldsmiths College in London. His tutor was F. L. Griggs, who had been working as an illustrator for the Highways and Byways series of books. These publications bought to light the modern ability to travel by bus, car or train around the country. Griggs pen drawings for these books, I would say, were the point when romantic nostalgia came back into fashion and his students would have been exposed to this.

‘He had a palm as delicate as gossamer,’ Sutherland remembered, it was his drawn illustrations to the thirteen volumes of the Highways and Byways guidebooks which had inspired both Piper and Sutherland as boys. When the older man offered both friendship and technical advice Sutherland was flattered to receive it. He and Paul Drury spent the Christmas of 1926 with Griggs learning about inking plates and printing them. Above all he helped to augment their growing enthusiasm for Palmer. †

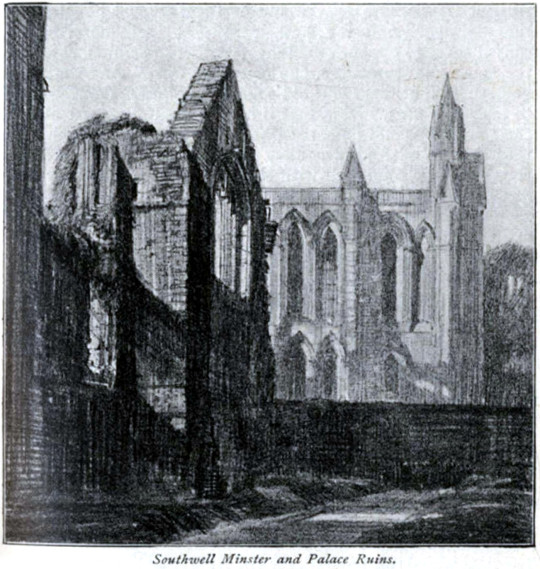

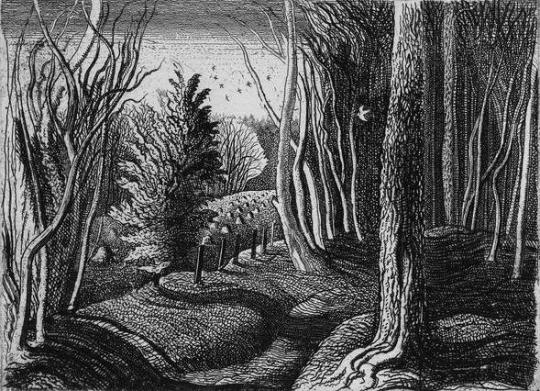

Samuel Palmer – Landscape, Girl Standing, 1826

In autumn 1924 William Larkins showed his friends a Palmer print The Herdsman’s Cottage, which he had bought in Charing Cross Road. This tiny work came as a revelation to them all. Sutherland recalled: I remember I was amazed by its completeness, both emotional and technical. It was unheard of at the school to cover the plate almost completely with work and quite new to us that the complex variety and multiplicity of lines could form a tone of such luminosity. †

The landscapes were daring and drawn from unexpected viewpoints: The Girl in the Ploughed Field astonished me with its total disregard for conventional composition. The drawing is almost what we today call naïf. †

So, as noted, the biggest change in style for Sutherland at this time from the teaching of Griggs into the engraving style of Palmer works would be to etching the sky. The image Number Fourty-Nine above from 1924 has a clean sky where as the images below have engraving all over the etching-plate.

In the 1920s, when photographs were being used as illustrations, the question of art was in doubt; why should an artist depict a scene when the camera can do the job for them? So the result was that an artist can bend reality. From this came an ideal eden like view of the past and a retelling of rural life before the invention of machines. Later on the art world would rebel against the camera and surrealist, cubist and impressionist styles would be invented.

The 1920s was the start of a revival for Palmer, unpublished plates were being printed, the Medici Society published his other works for the public and books were being scribed.

Other artists worth noting are Robin Tanner or Paul Drury, both new converts to the church of Samuel Palmer’s work. These men walked the first steps in the world of the New Romantics, coming out of Goldsmiths College at that time.

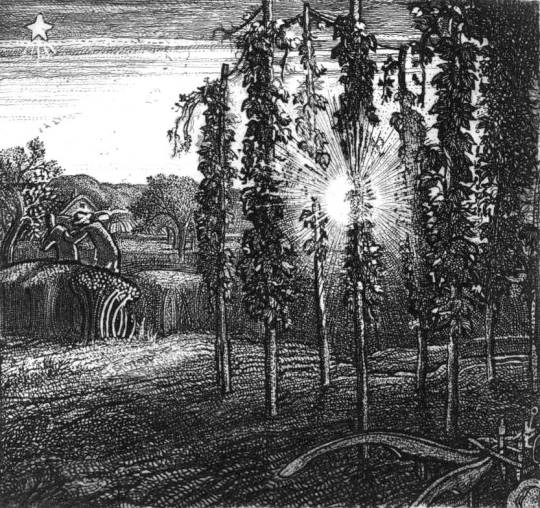

Paul Drury – September, 1928

Robin Tanner – The Road Mender, 1928

All men at the same time made an impact on the artworld and they all shared themes, knowingly or not. Below are the etchings of Sutherland.

Graham Sutherland – Wood Interior, 1929

Graham Sutherland – Cray Fields, 1925

Graham Sutherland – Pecken Wood, 1925

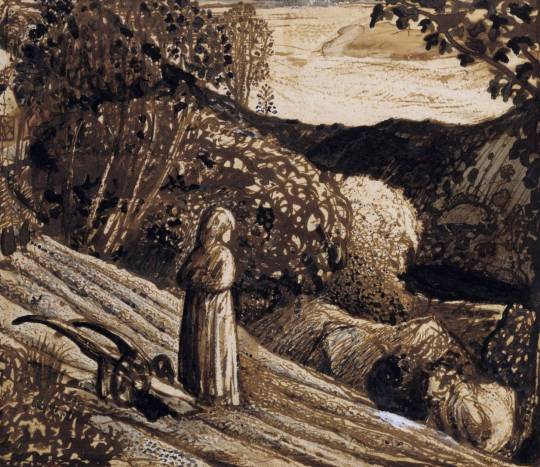

I thought it worth including this study by Sutherland of a print. Looking more like a mono-print it has all the qualities of Palmer’s work as it is done in ink and oil paint. The final etching is below.

Graham Sutherland – Sketch for Pastoral, 1930

Graham Sutherland – Pastoral, 1930

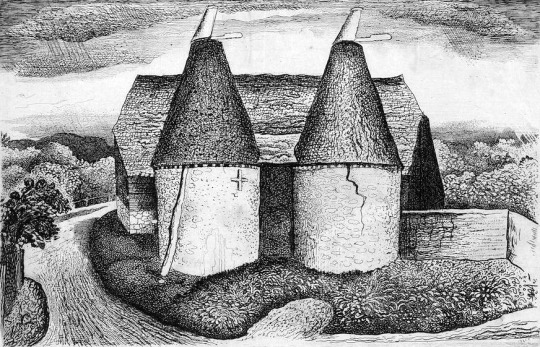

Graham Sutherland – Oast House, 1932

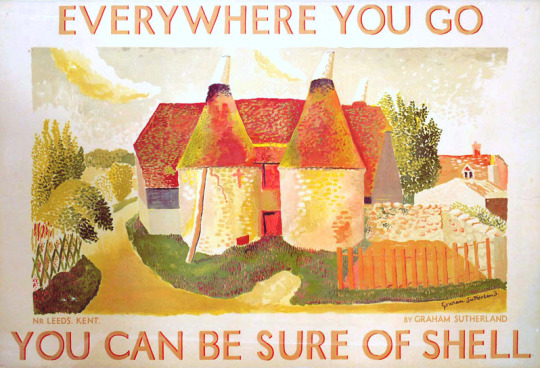

These words would get translated in various styles into Sutherland’s work but one of the most restrained and pleasing was this Shell Poster.

Graham Sutherland – Shell Poster – Oust Houses, Near Leeds, Kent, 1932

† The Spirit of Place: Nine Neo-Romantic Artists and Their Times, 2001, p108

Stuart Sillars – British Romantic Art and the Second World War, 1991, p42