This is an article I found in a book about the open house exhibitions of Great Bardfield, posted in the Daily Mail. 7th July, 1955. It rather overlooks the work of the women, but I enjoyed the tail of Bawden getting a bucket of water thrown over him.

‘Come Into My Parlour,’ say the Artists of this Village Academy.

The population of Great Bardfield, an Essex village about 40 miles from London, is 900. Its attractions include four pubs and nine artists.

This works out at an average of 2.25 artists per pub, a dispersion sufficient to enable them to co-exist amicably in so far as artists ever can it being well known that an artists’ colony is one of the trickiest of all colonial enterprises.

Great Bardfield’s nine sternly insist that they are not a Group or a School, but nine people who happen to live in the same village. Once in a while, however, they become collective, if not a group and give an exhibition of their work in their homes. They nibbled at this idea of a village academy in 1951 and tried it out more thoroughly last car. From tomorrow until July 17 they hope to establish the Great Bardfield Summer Exhibition as a regular event.

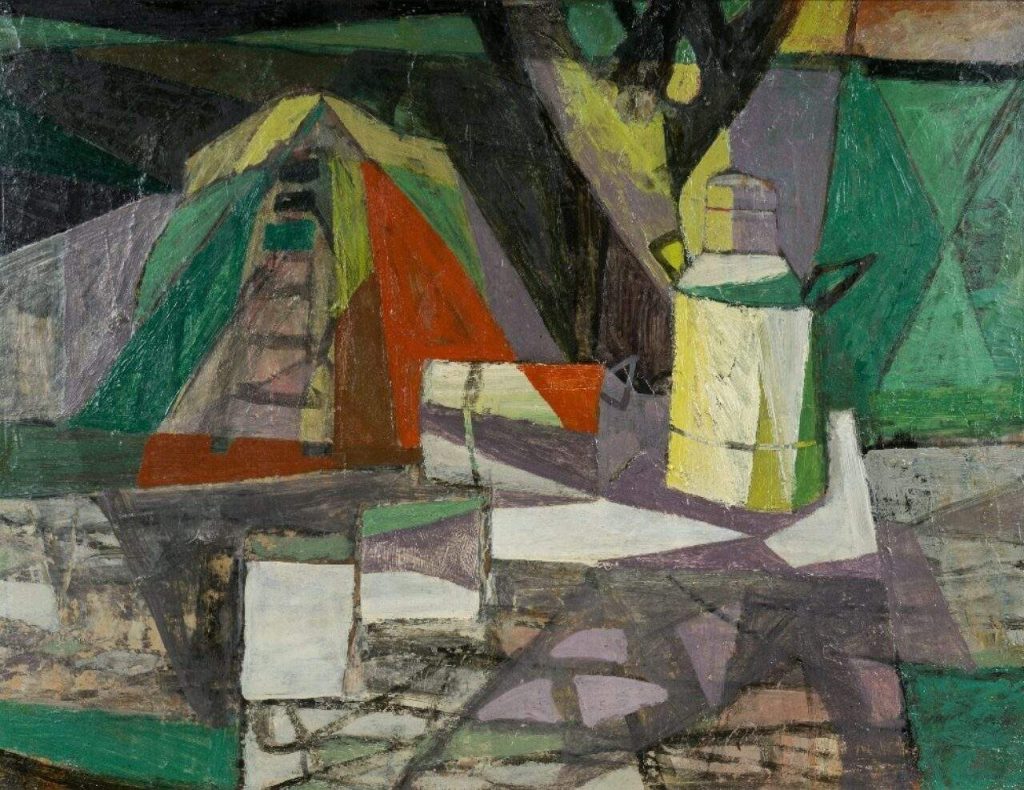

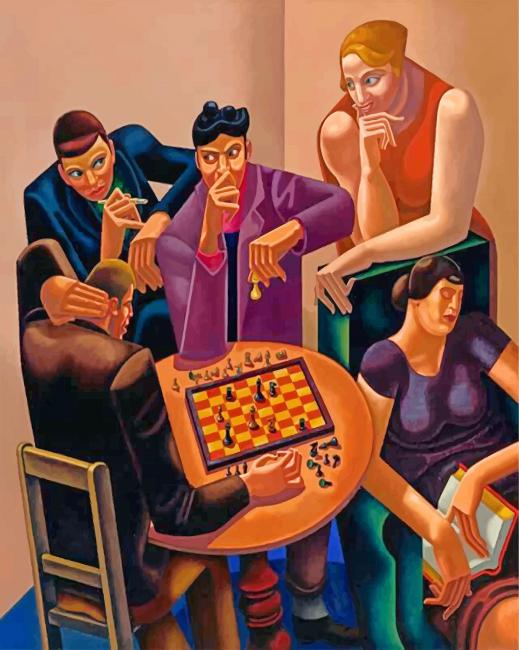

At one end of the village you can find John Aldridge, A.R.A. whose traditional landscapes of the neighbouring countryside are spiritual descendants of Constable, who operated not many miles east of here. In contrast at the other end of the village (and of art) is Clifford-Smith, who goes in for a modern expressionist treatment of the human figure that is vigorous, emotional, and Mediterranean in feeling. In Clifford-Smith’s house there will also be a display of cartoons by Low, another Great Bardfielder.

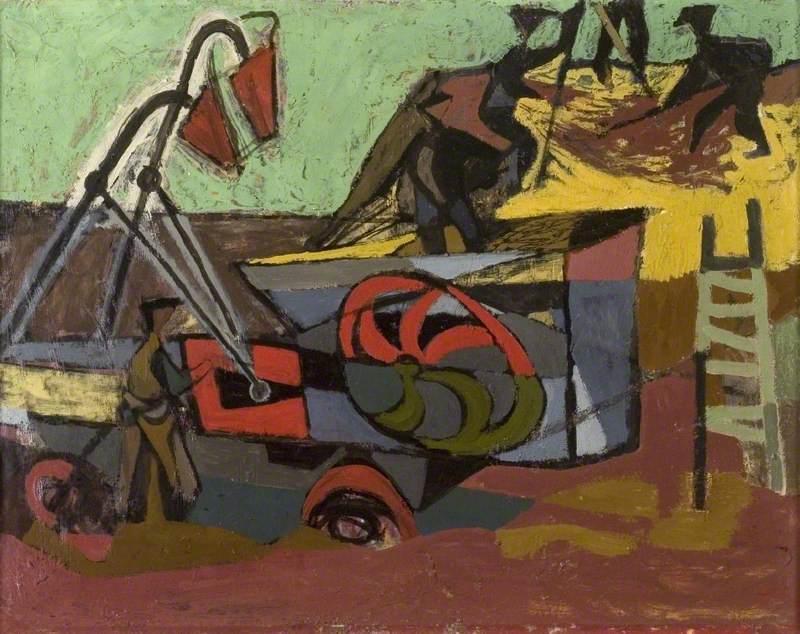

In the 80 yards or so between the two houses you will find the others. Michael Rothenstein, like Aldridge, finds his inspiration round the corner. A typical Rothenstein lino-cut print shows a cornfield in which a roguish, slightly fantasticated tractor seems to be revelling in country life more than the man perched on it-who is probably working out his overtime pay.

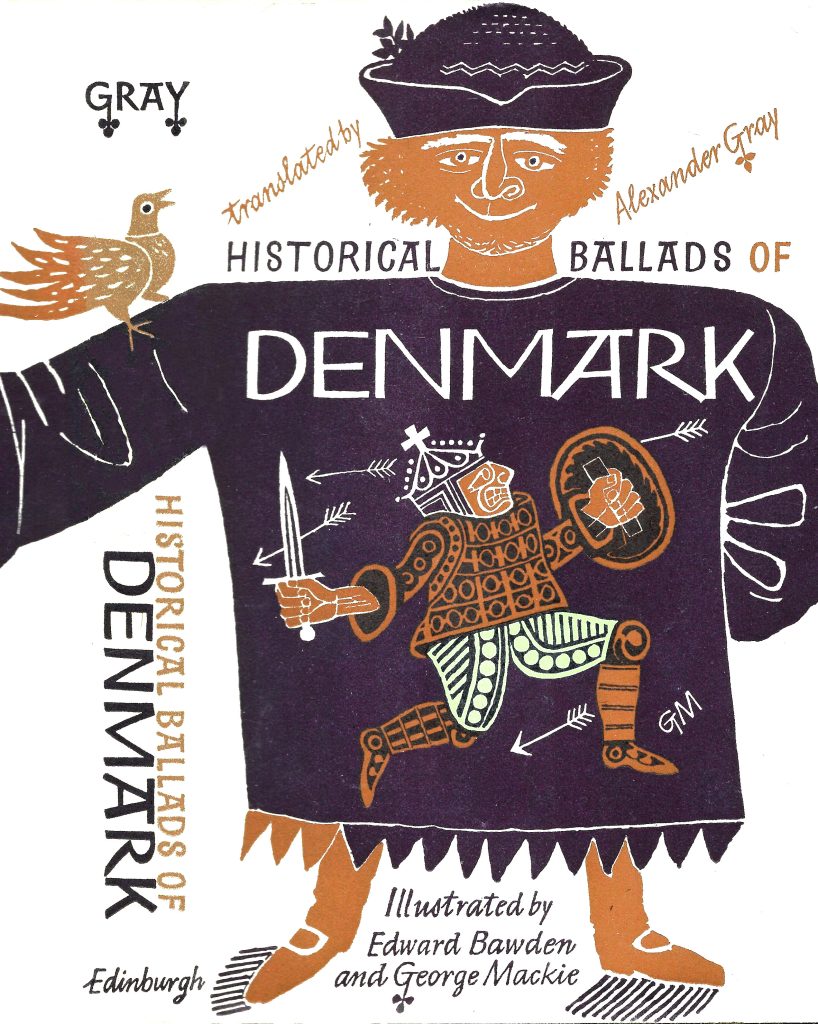

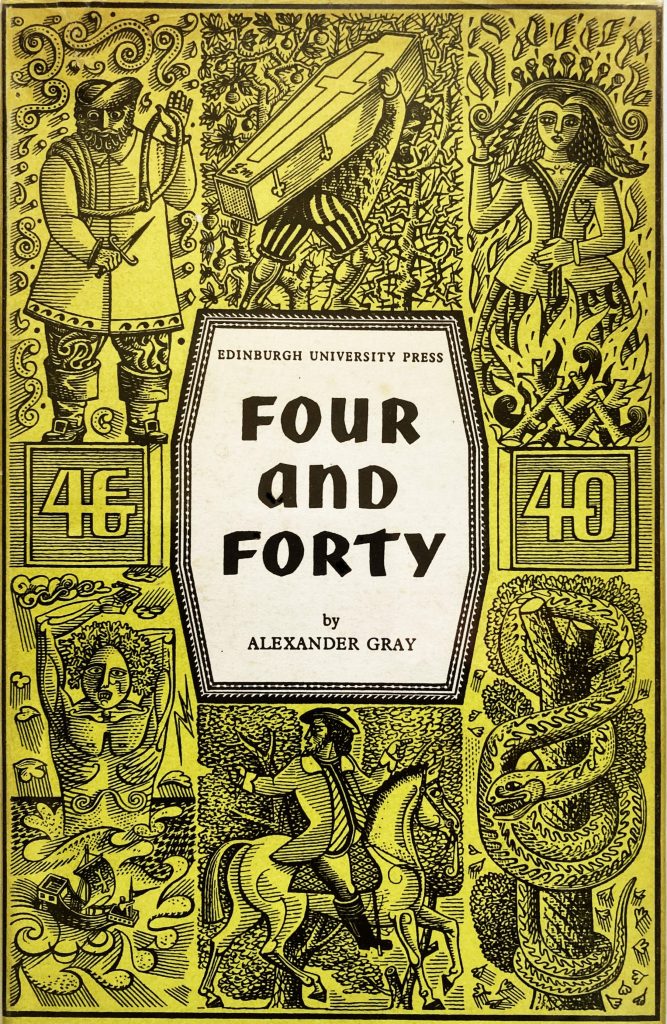

By way of contrast George Chapman, who is in love with the mining villages of Wales, is showing a batch of paintings which, if laid end to end, would add up to the Rhondda Valley. Across the road, by the post office which is also a grocer’s and draper’s, lives Edward Bawden, A.R.A., the only one of the nine who is a genuine native.

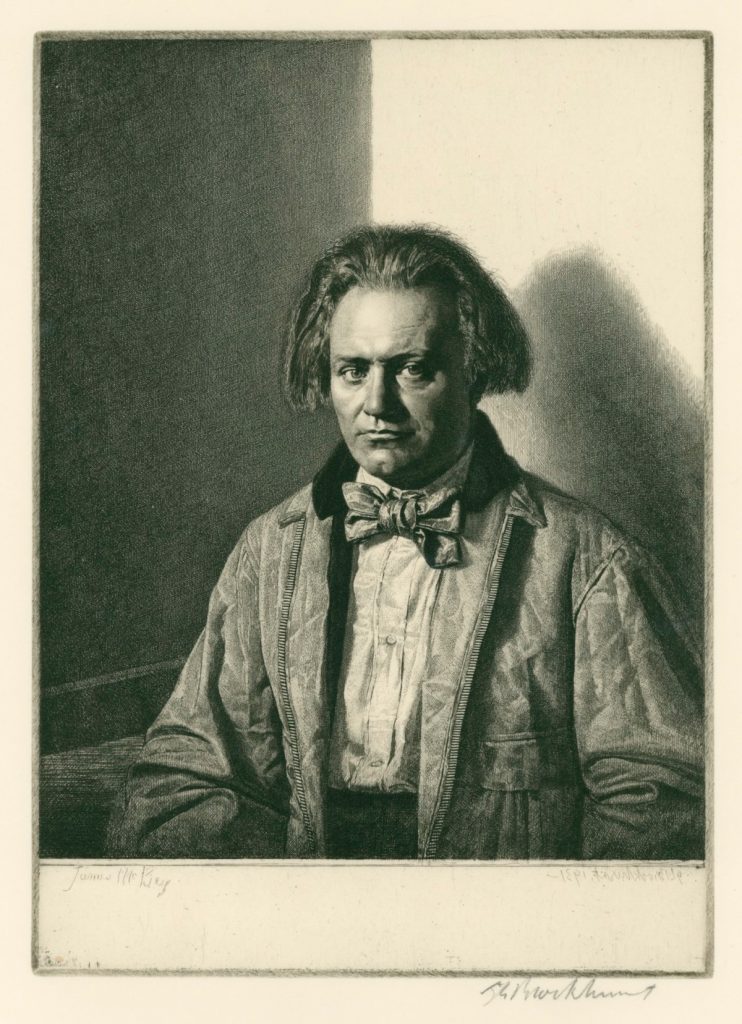

A somewhat lugubrious looking man, Bawden cycles off in an old mac to find material for his nationally esteemed watercolours in the byways of the neighbourhood. Coming across him crouched in a ditch or huddled against a wall glumly scratching away at his pad you might take him for a private detective keeping watch on the cottage opposite. Once a suspicious farmer’s wife tipped a bucket of water over him, unaware that her house was being immortalised.

The other exhibitors are Walter Hoyle, Marion Straub, and Audrey Cruddas, who designs costumes and scenery for the Old Vic in a studio above the village café.

Charging less

B y holding the Exhibition in their homes the artists can charge up to a third less for their work, as they save the cost of transporting the stuff to London and paying the dues exacted by London galleries. For the public it is therefore a chance to pick up a future old master cheap.

What do the villagers think about it all?

Little Bert probably spoke for most of them when he told me guardedly: “I haven’t heard no complaints.” Last year, however, a few did betray their Essex caginess to the extent of being impressed by the traffic problem which the Exhibition brought to a village where normally not more than two or three cars are visible at the same time. (P.C. Plummer, whose headache this will be, is the subject of a painting by Bawden in the current Royal Academy.)

Clifford-Smith, who often plies the palette knife with generosity, treasures the remark of the retired cowman who peered long and intently at his paintings and then came up with: “Of loikes the thick ‘uns best.”

Not her idea

The women of the village have a different approach to art. One, who spent an afternoon diligently visiting every house and was then asked what she thought of the pictures, looked blank. “Pictures? Oh, the pictures! I didn’t have time to look at them. It was their houses I wanted to see.”

The landlord of The Vine, who admires all nine artists with diplomatically equal fervour, admits under pressure that the Exhibition does not particularly boost bar receipts. It seems that those who thirst for culture do not on the whole thirst for anything else. (I recall in this connection one of the empresses of the West End theatre bars once dismissing the work of an eminent but rather highbrow dramatist as “just a tea-and-ices show, dear.”)

Perhaps the hardest lot is that of the wives. Not only must they endure the invasion of their homes between 11 and 7 daily for ten days (while continuing to feed the children and appease the daily help), but they must simulate, without stopping, a fixed grin of warm hospitality.