This is the obituary of Edward Bawden by Quentin Blake from the RSA Journal, February 1990.

Edward Bawden was born in Braintree in Essex in 1903. His father was an ironmonger, and Bawden has claimed to be, from his father’s point of view, something of a failure in that he did not follow him into that calling. He went instead to Cambridge Art School and then to the Royal College of Art. There (where he also met Eric Ravilious) he was influenced by Paul Nash, who was a visiting tutor at the time.

The Nash influence is evident in his earliest work, but Bawden very quickly found his own way of doing things, and a variety of commissions, many of them from the Curwen Press, which in those days (the late twenties and early thirties) was able to commission work much as a good design group might today. Among these projects were many small drawings for advertisements and brochures, as well as illustrations for books. Some of these were tasks that many another illustrator would have thought humble enough not to demand much attention but Bawden carried out the smallest drawing with complete professionalism and engagement. Each is beautifully and economically designed, with an unerring sense of the effect of the drawing on the page, and spiked with idiosyncratic wit and vivacity.

In 1932 Bawden married Charlotte Epton; they had two children, Joanna and Richard (himself an artist). They lived at Great Bardfield in Essex, in the house that Bawden’s father had bought for him. Bawden’s practice continued to expand. It embraced book illustration, posters, prints, watercolours, murals and wallpaper; and this despite the fact that he lacked what any young illustrator today would regard as an essential piece of equipment, a telephone. Urgent messages came, apparently, via the butcher next door.

All this was interrupted, or at least given a new direction, by the outbreak of war. Bawden was appointed an Official War Artist. He travelled in France, in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Africa. He seems to have relished even the vicissitudes. In 1943 the ship on which he was returning from the Middle East was torpedoed and he spent five days in an open boat. “There was quite a lot to watch’, he observed characteristically, in a recent interview for the Artist’s and Illustrator’s Magazine, ‘sharks nosing round all the time, plenty of dead bodies floating about in different positions.”

The rich store of work that he brought and sent back in these war years was perhaps less about the experience of war than about Bawden discovering new possibilities of his art in the traditional British role of the solitary traveller. ‘Ravilious and I were detached observers, watching and waiting…, he once wrote. It was this balance of detachment and enthusiasm that helped to give his work its distinctive quality; and explains his success at giving an intimate sense of England that was nonetheless free of nostalgia. Love is expressed by the quality of observation. Bawden was an observant traveller in Essex as well as among the Marsh Arabs, and saw with the same eye.

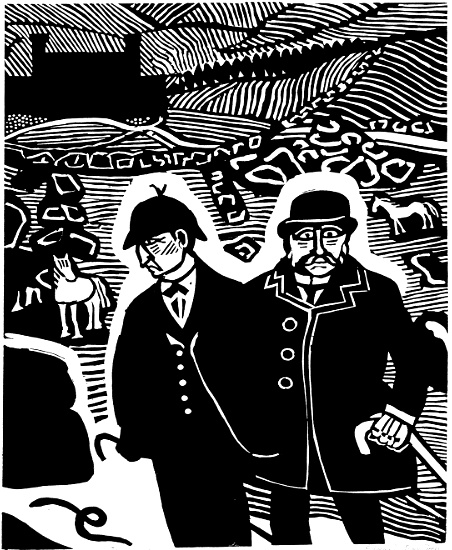

After the war he was immediately back to another forty years of work: impossible to mention it all. His unsentimental eye for the Victorian was just right for the Festival of Britain, and his huge, coloured, spirited Lion & Unicorn presided over that pavilion as it has done, subsequently, over so many degree-giving ceremonies at the RCA. Particularly significant, it seems to me, were the books that he illustrated for the Folio Society such as Gulliver’s Travels and Rasselas. Not ‘commercial’ editions nor éditions de luxe but books as they should be: balanced, intelligent, witty, well-designed. In the early eighties (and in his early eighties) the Folio Society invited Bawden to illustrate a book of his own choice. The Hound of the Baskervilles took them completely by surprise but it became, once again, an emphatic and characteristic work.

In the spring of 1989 I visited Bawden in his studio in Saffron Walden. We looked at both the wallpapers he had designed in 1928 (printing them from linocuts on the floor of his bed sitting room in Redcliffe Road) and a new linocut of a frog that he had just completed, sixty years later, to go on sale at his new exhibition at the V & A. It showed no diminution of authority in its handling. On that occasion we walked down from the Fry Art Gallery, where Bawden’s work appears among that of other Essex artists, to his home. Bawden was using a stick, and, though he didn’t much seem to need it, at one point he staggered slightly. His friend, the artist John Norris Wood, who was with us, said ‘Be careful language for use at sea. Edward. You’re falling into the gutter’. Bawden picked up the message through his deafness. ‘It’s where I belong,’ he said cheerfully. ‘It’s where I belong.”

However, he was not in the gutter, and nor, indeed, is his reputation. It is gratifying to think that he lived to see it enhanced anew, with a range of exhibitions, interviews and commentary. Yet I wonder if I am alone in thinking that we have not quite yet arrived at a full estimate of his worth. To have found a way of being modern without being ephemeral; to establish a high quality of design without foregoing idiosyncrasy; to master so many disciplines, and continue to do so over so long a period: this seems to me no small achievement.

And his working life is in itself a strengthening example to anyone involved in art and design. One is heartened, and not surprised, to learn that on the last day of that inspiring life he was at work cutting a new piece of lino, starting a new print.