’I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from men who are fighting to those who want the war to go forever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.’ – Paul Nash

This is a post about four artists and their reactions to war through their art.

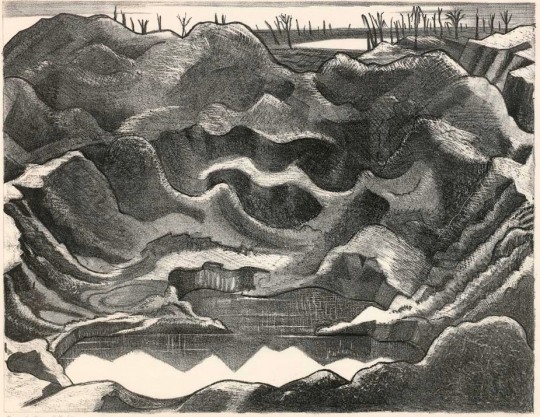

Paul Nash – Mine Crater. Hill 60. December 1917- Stone Lithograph.

The Art of Paul Nash for the war was a remarkable thing. Graphic in detail of metaphor and gloom they showed the public, at home in Britain, the front line. Nash was supported by a host of art critics and writers that wrote to the nervous Admiralty reaffirming that these works must be seen by the public and not censored and locked away. The Sunday Times critic Frank Rutter wrote in August 1917:

“I have seen and studied carefully a number of Mr Paul Nash’s drawings and watercolours made in the Ypres salient and consider them to be among the best and most moving works of art dealing with the present war. Facilities enabling Mr Nash to produce further drawings and pictures of the Front could in my judgement only result in enriching contemporary British art.”

In the next year the War Office would control and present what the public saw of this art with the 1918 series of four magazines called ‘British Artists at the Front’. Volume one: CRW Nevinson, Volume two: Sir John Lavery, Volume three: Paul Nash and Volume four: Eric Kennington.

Paul Nash – Wire – Watercolour.

Francisco Goya (1746 – 1828) was a Spanish painter and printmaker. His early artistic works were oil paintings of romance and the Spanish court under Charles III. He’s also credited for painting one of the first totally nude, life-sized paintings in western art without mythological subtext.

Francisco Goya – The Third of May, 1808.

Towards the end of Goya’s life he produced a remarkable series of 80 etchings called ‘The Disasters of War’. The etchings and aquatints depict a set of scenes from the Spanish struggle against the French army under Napolean Bonaparte, who invaded Spain in 1808. When Napolean tried to install his brother Joseph Bonaparte, as King of Spain, the Spanish fought back, eventually aided by the British and the Portugese.

Above is the painting ‘The Third of May’, painted in 1814. Goya sought to commemorate Spanish resistance to Napoleon’s armies during the occupation. During this time Goya was still a court painter, now under the French and may have been seen as a collaborator by some. Painted while the print series was in progress it marked a change in style, with a darker and more sinister attack on the French and a show of patriotism for the sacrificed Spanish.

Francisco Goya – Esto es peor (This is worse)

The prints show the French as a merciless army and the people in the crossfire, confused or abused victims. Some of the prints are supernatural. They are mostly divided into three styled themes:

war, famine, and political and cultural allegories. Goya travelled the battle fields and towns in the conflict to sketch out plans for the works. Above in ‘Esto es peor’, the image shows the aftermath of a battle with the mutilated torsos and limbs of civilian victims, mounted on trees, like fragments of marble sculpture.

Francisco Goya – Por una navaja (For a clasp knife).

Above from ‘Por una navaja’, a garrotted priest grasps a crucifix in his hands. Pinned to his chest is a description of the crime for which he was killed – possession of a knife, that hangs from a cord around his neck. His body tied to an execution post while the bystanders look away in horror. This again is an image of horror after the event, with the consequences being witnessed by the civilians.

As graphic as the images were and even with ten years spent on their execution, it wasn’t until after Goya’s death that the prints where published. While it is unclear how much of the conflict Goya witnessed, it is generally accepted that he observed first-hand many of the events recorded.

The distance from the publication of Goya’s prints from the events helped them not be censored and with the war won, they reaffirmed Spain’s national pride.

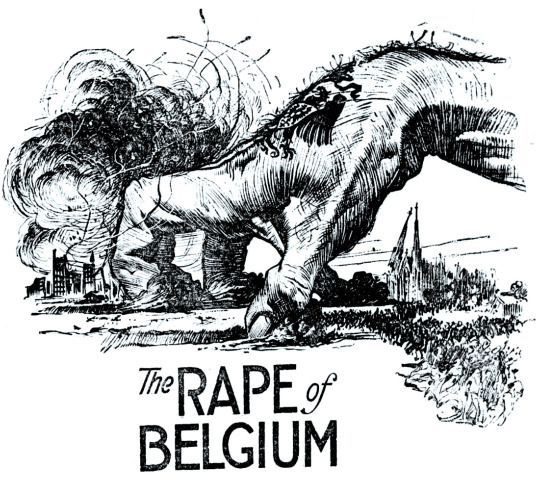

USA propaganda to build popular support for American intervention in the European war, WW1. Note the Germanic tattoo on the hand.

Censorship of art is always something of contemporary issue. A few years before Nash’s works of the battle fields in the early months of World War One was the ‘The Rape of Belgium’.

Belgium at the start of the war was in a state of neutrality from the 1839 ‘Treaty of London’. Under the treaty, the European powers recognised and guaranteed the independence and neutrality of Belgium. Article VII required Belgium to remain perpetually neutral, and by implication committed the signatory powers to guard that neutrality in the event of invasion.

The German army desired to invade Belgium to face the French forces and in doing so the German army engaged in numerous atrocities against the civilian population of Belgium, defying the Treaty.

A destroyed Leuven. The Germans burned the city from August 25 to 2 September 1914.

The outcome was the ransacking and burning of civilian, church and government property; 6,000 Belgians were killed, 25,000 homes and other buildings in 837 communities destroyed in 1914 alone. One and a half million Belgians (20% of the entire population) fled from the invading German army. The Germans killed 27,300 Belgian civilians directly, and an additional 62,000 via the deprivation of food and shelter.

Pierre-Georges Jeanniot – IV – The Massacre at Surice

In reaction to the 1914 carnage and maybe after Goya, Pierre-Georges Jeanniot produced a series of ten etchings in 1915 called ‘The Horrors of War’.

Jeannoit’s first exhibited the works in Paris for less than a day before the French police banned it on fear it would cause panic amongst the Parisian population. The etching plates where locked in a box and lost, only to be rediscovered nearly 100 years later.

Pierre-Georges Jeanniot – X – In The Church

These etchings, show a detailed situation of an atrocity, where as Goya’s works are almost surreal illustrations of war-craft. They were found and restored by Mark Hill who has had a limited edition printed of them. This posthumous edition was officially published on 4th August 2014, the centenary of the invasion of Belgium and the start of World War One.

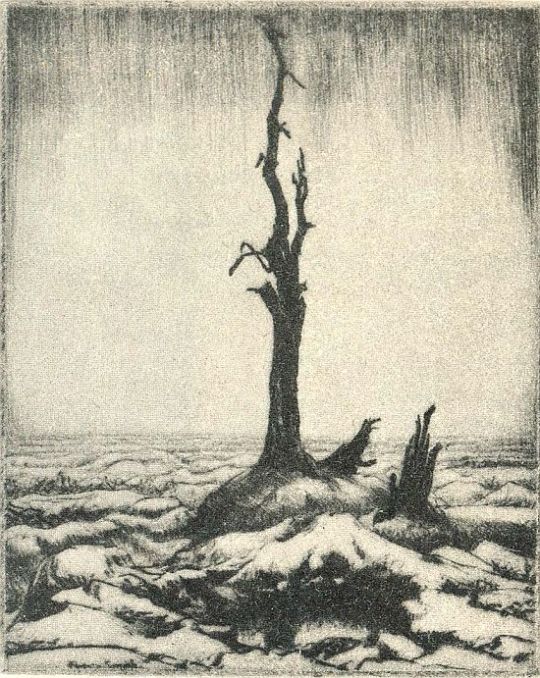

Percy Smith – Death Waits

The last printmaker I want to look at is Percy Delf Smith. Smith made two series of war prints. ‘Drypoints of the War’ and ‘Dance of Death’ – both series of prints documenting life on the Western Front of the First World War.

In 1916 he joined the Royal Marine Artillery and arrived at the Somme in October. He served as a gunner until 1919 in France and Belgium. Rather like Jeanniot, Smith witnessed the Germans destruction of Belgium.

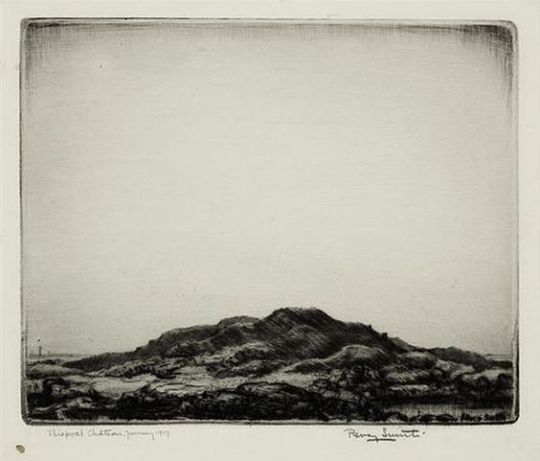

At the start of 1917 Percy Smith was located in Thiepval, Belgium where Lutyens’ Memorial to the Missing of the Somme now stands. When the Germans entered Thiepval on 26 September 1914, the village and its château were utterly destroyed. Smith’s diary entries describe the desolate landscape:

Thurs. 4th (January 1917) ‘Trenching’ as usual. No shelling. Went over Thiepval hill. Thiepval simply a heap of rubbish decorated by gaunt tree trunks. Must sketch it. Finished reading Doyle’s ‘The White Company’ war as it was and read about while the guns cracked’.

Percy Smith – Thiepval Chateau, 1917 – from Sixteen Drypoints of War

Smith was covert about his drawings of time at the front line and was arrested twice of being a spy. He smuggled etching plates in books and magazines both too the front line and home. He printed ‘Drypoints of the War’ while on leave in 1917.

Percy Smith – Thiepval, from Sixteen Drypoints of War, 1917

The ‘Drypoints of War’ are very matter of fact, they are images of the landscape and its desolation that was all around, similar in subject matter to the works of Paul Nash. Destruction with abstraction.

The second series of prints ‘Dance of Death’ was less of a witnessing of war and more of an attack of it. With death always watching, waiting or lingering with the solders, they were produced after the war in 1919.

Percy Smith – The Dance of Death No. 1: Death forbids

In ‘Death forbids’, a hand of the solder that is pinned down by a fallen tree and in the barbed wire reaches up, trying to get the attention of the medics and stretcher bearers to the top left of the picture. I am sure the skeletal death is meant to look harrowing and like he is suppressing the man, but to me it looks affectionate and like death is helping the man surrender to the fate.

Percy Smith – The Dance of Death No. 3: Death awed.

In ‘Death awed’ we are presented with a death, shocked and impressed by the might of war, the carnage and ballistics of force that don’t even leave a body but two boots with broken bones in the wet earth.

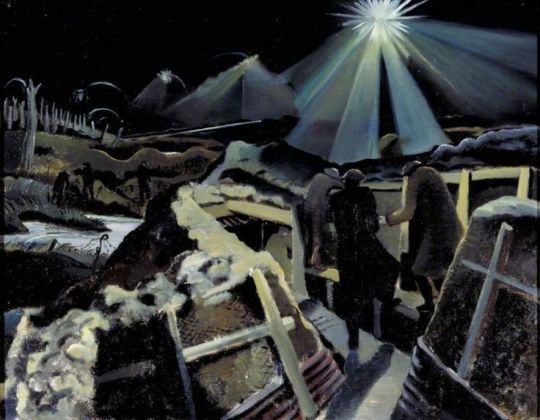

Paul Nash – Ypres Salient At Night, 1918.